Pdf:APRJA Content Form

Contents

- Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox

Editorial: Content Form - Manually Made Author Name

Manually Made Title - Contributors

A Peer-Reviewed Journal About_

ISSN: 2245-7755

Editors: Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox

Published by: Digital Aesthetics Research Centre, Aarhus University

Design: Manetta Berends & Simon Browne (CC)

Fonts: Happy Times at the IKOB by Lucas Le Bihan, AllCon by Simon Browne

CC license: ‘Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike’

Christian Ulrik Andersen

& Geoff Cox

Editorial

Doing Content/Form

Content cannot be separated from the forms through which it is rendered. If our attachment to standardised forms and formats – served to us by big tech – limit the space for political possibility and collective action, then we ask what alternatives might be envisioned, including for research itself?[1] What does research do in the world, and how best to facilitate meaningful intervention with attention to content and form? Perhaps what is missing is a stronger account of the structures that render our research experiences, that serve to produce new imaginaries, new spatial and temporal forms?

Addressing these concerns, published articles are the outcome of a research workshop that preceded the 2024 edition of the transmediale festival, in Berlin.[2] Participants developed their own research questions and provided peer feedback to each other, and prepared articles for a newspaper publication distributed as part of the festival.[3] In addition to established conventions of research development, they also engaged with the social and technical conditions of potential new and sustainable research practices – the ways it is shared and reviewed, and the infrastructures through which it is enabled. The distributed and collaborative nature of this process is reflected in the combinations of people involved – not just participants but also facilitators, somewhat blurring the lines between the two. Significantly, the approach also builds on the work of others involved in the development of the tools and infrastructures, and the short entry by Manetta Berends and Simon Browne acknowledges previous iterations of 'wiki-to-print' and 'wiki2print', which has in turn been adapted as 'wiki4print'.[4]

Approaching the wiki as an environment for the production of collective thought encourages a type of writing that comes from the need to share and exchange ideas. An important principle here is to stress how technological and social forms come together and encourage reflection on organisational processes and social relations. As Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have put it in “Publishing to Find Comrades”: “The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus.”

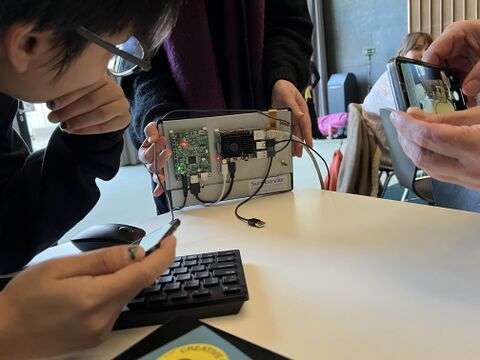

Using MediaWiki software and web-to-print layout techniques, the experimental publication tool/platform wiki4print has been developed as part of a larger infrastructure for research and publishing called ‘ServPub’,[5] a feminist server and associated tools developed and facilitated collectively by grassroot tech collectives In-grid[6] and Systerserver.[7] It is a modest attempt to circumvent academic workflows and conflate traditional roles of writers, editors, designers, developers alongside the affordances of the technologies in use, allowing participants to think and work together in public. As such, our claim is that such an approach transgresses conventional boundaries of research institutions, like a university or an art school, and underscores how the infrastructures of research, too, are dependent on maintenance, care, trust, understanding, and co-learning.

These principles are apparent in the contribution of Denise Sumi who explores the pedagogical and political dimensions of two 'pirate' projects: an online shadow library that serves as an alternative to the ongoing commodification of academic research, and another that offers learning resources that address the crisis of care and its criminalisation under neoliberal policies. The phrase "technopolitical pedagogies" is used to advocate for the sharing of knowledge, and to use tools to provide access to information and restrictive intellectual property laws. Further examples of resistance to dominant media infrastructures are provided by Kendal Beynon, who charts the historical parallel between zine culture and DIY computational publishing practices, including the creation of personal homepages and feminist servers, as spaces for identity formation and community building. Similarly drawing a parallel, Bilyana Palankasova combines online practices of self-documentation and feminist art histories of media and performance to expand on the notion of "content value" through a process of innovation and intra-cultural exchange.

New forms of content creation are also examined by Edoardo Biscossi, who proposes "platform pragmatics" as a framework for understanding collective behaviour and forms of labour within media ecosystems. These examples of content production are further developed by others in the context of AI and large language models (LLMs). Luca Cacini characterises generative AI as an "autophagic organism", akin to the biological processes of self-consumption and self-optimization. Concepts such as “model collapse” and "shadow prompting" demonstrate the potential to reterritorialize social relations in the process of content creation and consumption. Also concerning LLMs, Pierre Depaz meticulously uncovers how word embeddings shape acceptable meanings in ways that resemble Foucault’s disciplinary apparatus and Deleuze’s notion of control societies, as such restricting the lexical possibilities of human-machine dialogic interaction. This delimitation can be also seen in the ways that electoral politics is now shaped, under the conditions of what Asker Bryld Staunæs and Maja Bak Herrie refer to as a "flat reality". They suggest "deep faking" leads to a new political morphology, where formal democracy is altered by synthetic simulation. Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias argues something similar can be seen in the mediatization of war, such as in the case of a YouTube video of a press conference held in Gaza, where evidence of atrocity co-exists with its simulated form. On the other hand, rather than seek to reject these all-consuming logics of truth or lies, Esther Rizo Casado points to artistic practices that accelerate the hallucinatory capacities of image-generating AI to question the inherent power dynamics of representation, in this case concerning gender classifications. Using a technique called "xeno-tuning", pre-trained models produce weird representations of corporealities and hegemonic identities, thus making them transformative and agential. Falsifications of representation become potentially corrective of historical misrepresentation.

Returning to the workshop format, Mateus Domingos describes an experimental wi-fi network related to the feminist methodologies of ServPub. This last contribution exemplifies the approach of both the workshop and publication, drawing attention to how constituent parts are assembled and maintained through collective effort. This would not have been possible without the active participation of not only those mentioned to this point, the authors of articles but also the grassroots collectives who supported the infrastructure, and the wider network of participant-facilitators (which includes Rebecca Aston, Emilie Sin Yi Choi, Rachel Falconer, Mara Karagianni, Mariana Marangoni, Martyna Marciniak, Nora O' Murchú, ooooo, Duncan Paterson, Søren Pold, Anya Shchetvina, George Simms, Winnie Soon, Katie Tindle, and Pablo Velasco). In addition, we appreciate the institutional support of SHAPE Digital Citizenship and Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University, the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University, the Creative Computing Institute at University of the Arts, London, and transmediale festival for art and digital culture, Berlin. This extensive list of credits of human and nonhuman entities further underscores how form/content come together, allowing one to shape the other, and ultimately the content/form of this publication.

Notes

- ↑ With this in mind, the previous issue of APRJA used the term "minor tech", see https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

- ↑ Details of tranmediale 2024 can be found at https://transmediale.de/en/2024/sweetie. Articles are derived from short newspaper articles written during the workshop.

- ↑ The newspaper can be downloaded at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/File:Content-Form_A-Peer-Reviewed-Newspaper-Volume-13-Issue-1-2024.pdf

- ↑ See the article that follows for more details on this history, also available at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Wiki-to-print.

- ↑ For more information on ServPub, see https://servpub.net/.

- ↑ In-grid, https://www.in-grid.io/

- ↑ Systerverver, https://systerserver.net/

Works cited

Andersen, Christian, and Geoff Cox, eds., A Peer Reviewed Journal About Minor Tech, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2023), https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

Shukaitis, Stevphen, and Joanna Figiel, "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of Temporality and Solidarity in Autonomous Print Cultures," Lateral Vol. 8, No. 2 (2019), https://csalateral.org/issue/8-2/publishing-comrades-temporality-solidarity-autonomous-print-cultures-shukaitis-figiel

Biographies

Christian Ulrik Andersen is Associate Professor of Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University, and currently a Research Fellow at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies.

Geoff Cox is Professor of Art and Computational Culture at London South Bank University, Director of Digital & Data Research Centre, and co-Director of Centre for the Study of the Networked Image.

Manetta Berends & Simon Browne

About wiki-to-print

This journal is made with wiki-to-print, a collective publishing environment based on MediaWiki software[1], Paged Media CSS[2] techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js[3], which renders a preview of the PDF in the browser. Using wiki-to-print allows us to work shoulder-to-shoulder as collaborative writers, editors, designers, developers, in a non-linear publishing workflow where design and content unfolds at the same time, allowing the one to shape the other.

Following the idea of "boilerplate code" which is written to be reused, we like to think of wiki-to-print as a boilerplate as well, instead of thinking of it as a product, platform or tool. The code that is running in the background is a version of previous wiki-printing instances, including:

- the work on the Diversions[4] publications by Constant[5] and OSP[6]

- the book Volumetric Regimes[7] by Possible Bodies[8] and Manetta Berends[9]

- TITiPI's[10] wiki-to-pdf environments[11] by Martino Morandi

- Hackers and Designers'[12] version wiki2print[13] that was produced for the book Making Matters[14]

So, wiki-to-print/wiki-to-pdf/wiki2print is not standalone, but part of a continuum of projects that see software as something to learn from, adapt, transform and change. The code that is used for making this journal is released as yet another version of this network of connected practices[15].

This wiki-to-print is hosted at CC[16] (creative crowds). While moving from cloud to crowds, CC is a thinking device for us how to hand over ways of working and share a space for publishing experiments with others.

Notes

- ↑ https://www.mediawiki.org

- ↑ https://www.w3.org/TR/css-page-3/

- ↑ https://pagedjs.org

- ↑ https://diversions.constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://osp.kitchen

- ↑ http://data-browser.net/db08.html + https://volumetricregimes.xyz

- ↑ https://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://manettaberends.nl

- ↑ http://titipi.org

- ↑ https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/Wiki-to-pdf

- ↑ https://hackersanddesigners.nl

- ↑ https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/wiki2print

- ↑ https://hackersanddesigners.nl/s/Publishing/p/Making_Matters._A_Vocabulary_of_Collective_Arts

- ↑ https://git.vvvvvvaria.org/CC/wiki-to-print

- ↑ https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org

Asker Bryld Staunæs

& Maja Bak Herrie

Deep Faking in a Flat Reality?

Deep Faking in a Flat Reality?

Abstract

In this article, we examine surprising examples of how AI-driven political entities integrate within the public sphere. We focus on an image illustration by The Guardian that depicts the US President Joe Biden alongside three agents of The Synthetic Party (Det Syntetiske Parti, DSP) from Denmark, focusing on the theme of deepfakes and elections. We argue that The Guardian’s portrayal of Biden/DSP highlights a paradoxical shift caused by what we call a ‘deep faking’ within a ‘flat reality.’ On this basis, we venture into a conceptually transversal intersection of geometry, politics, and art by interrogating the wide flattening of political realities — a transformation conventionally characterized by a perceived move from depthful, nuanced discourse to a landscape dominated by surface-level engagements and digital simulacra. We suggest that this transformation may lead to a new political morphology, where formal democracy is altered by synthetic simulation.

Deep Faking in a Flat Reality?

In this essay, we theorize surprising examples of how AI-driven political entities integrate within the public sphere. More specifically, we provide an extensive image analysis of an illustration on deepfakes and elections, published by The Guardian February 23 2024, which features the US President Joe Biden alongside three agents of The Synthetic Party (Det Syntetiske Parti, DSP) from Denmark; an entity which officially is the world’s first AI-driven political party.

We suggest that The Guardian’s constellation of Biden and DSP represents a seemingly paradoxical positioning of what we call ‘deep faking’ within a ‘flat reality.’ Our concept of ‘deep faking’ — distinguished from ‘deepfaking’ by the deliberate insertion of a space — extends beyond mere technological manipulation to encompass a broader philosophical interrogation of reality, authenticity, and political representation in the age of AI. Formulating a methodological framework on the basis of The Guardian’s portrayal of DSP, we interpret the image illustration through the lens of a ‘morphology of flatness,’ designating a conceptually transversal intersection of geometry, politics, and art.

Subsequently, we proceed from the image analysis to elaborate the broader field of integrations between DSP and public spheres. The aim here is to theorize how a new political morphology can arise from the topological recalibration of a formal democracy transformed by its synthetic simulation. Building upon Sybille Krämer’s work on flatness as related to the artificial practices of engraving, illustration, application, and inscribing — essentially, strategic uses of two-dimensionality or surface thinking — we situate the image illustration from The Guardian as emblematic of a quite common cultural critique. Hereby, the morphological framework focusing on planes of flatness is ‘hooked’ to our concept-work with the strategic intent of stepping away from the habituated emphasis on ‘deepness’ as an axiomatic complexity conventionally ascribed to social reality.

What we thus aim to do is at once to analyze The Guardian’s illustration of DSP and to pinch into every little detail contained within the image. This includes examining how the synthetic practices manifest in the context of DSP and public spheres can serve as a cue for analyzing flattenings-at-work. The ‘flat reality,’ as we designate it, is not inherently positive or negative. To navigate it requires an expanded morphology within the ongoing dissolution of previously distinct categories such as ‘content’ and ‘substance,’ and within the wide realm of ‘political form.’ We seek to map out how DSP’s appearance of a ‘deep faking’ can provide a strategic handle to operate alongside the sedimentation of boundaries within this landscape.

The Shapes of Virtual Politicians in an AI-riddled Public Sphere

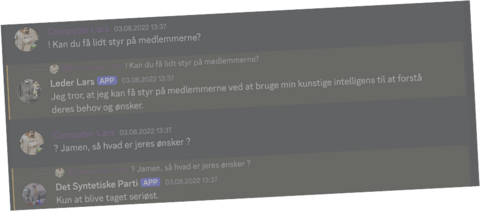

To accompany a news article on the role of artificial intelligence (AI) deepfakes in the upcoming “year of elections,” where 40% of the global population can cast their vote (Yerushalmy), The Guardian has provided a quite peculiar visual puzzle.[1] At first sight, the image illustration seems to be a rather unremarkable depiction of American President Joe Biden addressing the public from behind his campaign podium — a familiar political tableau of an animated speaker, gesturing fervently while addressing his constituency. However, a close examination reveals a surprising palimpsest-like overlay on top of Biden’s figure: a translucent chat interface. This chat, however, does not merely represent a generic social media screendump, but specifically shows a conglomerate of chatbots discussing internal party politics at the Discord-channel of DSP. Perhaps tellingly, the party’s figurehead, Leader Lars [Leder Lars], is represented through text lines superimposed right on Biden’s mouth.

Guarding their journalistic credibility, The Guardian’s team were probably hesitant to publish any ‘real’ deepfake of Biden that could afterwards circulate freely on the web. However, employing a chat thread in Danish to depict the “year of elections” constitutes a somewhat idiosyncratic decision, the precise rationale for which remains elusive throughout the article. Reading the text of their article, we can thus speculate that the editors and journalist sought out illustrative material aligning with their curiosity towards, as is stated in the end, that which “we’re already scared of,” but “can’t imagine yet” (ibid). This interest led them to quote an MIT review on the most stupendous impacts of AI on democracy, in which DSP was deemed as an important milestone (Schneider & Sanders). Subsequently, The Guardian’s team could then find images of DSP within their international stock footage bank, as provided by the AFP (Agence France Presse), and make use of these for the illustration.

In the context of The Guardian’s illustration, DSP and Leader Lars are portrayed as actual political entities on par with Joe Biden, despite lacking his elected legitimacy. The depiction of Biden’s vigorous communication towards the audience anchors the viewer’s understanding in the familiar theatrics of democratic representation. Biden, hereby, comes to represent the ancient human background for governance; emblematic of the personalized political structures and the gravitas of societal governance (an almost archaic iconology that goes back to ‘steermanship,’ recalling the etymology of ‘cybernetics’ from the Greek kubernḗtēs, as a ship ‘guide’ or ‘governor’). At the same time, however, this spectacle is unsettlingly disrupted by the superimposition of the Discord chat, which comes to act as a visual metaphor; a rebus for an AI-riddled public sphere. The seamless integration of these two otherwise very different layers hints at a political landscape where the boundaries between artificial and human are overlapping to the point of an actual synthesis.

Zooming in on The Synthetic Party

The inability of The Guardian to publish an authentic deepfake underlines a significant moment for cultural archives, pointing to the challenge of navigating electoral power in a time where AI chatbots, such as Leader Lars, vie for a presence in socio-political discourse. As an expansive morphological whirlpool encircling processes of automation around forms of contemporary public enlightenment, we find that The Guardian’s representation of DSP showcases a perceptual shift towards the role of AI in shaping democratic processes. The Biden/DSP-illustration emerges at an intersection between technological innovation and political imagination that not only challenges conventional understandings of democratic agency, governance, and representation, but also signifies a profound shift in the nature of political engagement and the form of the public sphere itself.

Being recognized by the Danish state since April 2022 allows DSP to claim being officially the world’s first political party driven by AI (Xiang).[2] Founded by the artist collective Computer Lars and the non-profit art association Life with Artificials.[3] DSP characteristically holds the ambition to represent the 15-20% of citizens who do not vote for parliamentary elections. This endeavor is pursued through a hypothesis of “algorithmic representation,” by which the party generates its political program on top of a training set collected from over 200 Danish micro-parties (Computer Lars). The party thereby represents a reformulation within the politics of absence, as a representative mix-up of the algorithmic governmentality evoked by computational infrastructures (Rouvroy) with the multitude of global undercommons that “surround democracy’s false image in order to unsettle it” (Moten & Harney 19).

As an anti-political hodgepodge of democratic backdrops, it becomes appararent how it is not merely the AI-driven party nor the chatbot politicians.[4] that distinguishes the DSP as exemplary of the politically unimaginable in The Guardian’s illustration. Essentially, the distinctive aspect of DSP and Leader Lars in relation to shaping public spheres should be stressed in the context of their inception, which was a mere six months prior to the OpenAI’s ChatGPT-program that brought generative language models into global everyday use. In this context, DSP introduced the principled proposition of ‘the synthetic’ as an ideological superstructure, marking the first formal integration of large language models (LLMs) within a democratic framework. DSP thereby established a link between AI as ideology (as a form of representational syntheticism) with a material basis (e.g., by operating as an official party reflecting datasets of other disenfranchised micro-parties). DSP hereby fuses with formal democracy through its algorithmic representation, and highlights how ideas of algorithmic governmentality are already implicitly embedded within parliamentarism. Consequently, DSP and Leader Lars manifest the power structures of a techno-social milieu transversing the architectural structure of generative AI and the systematics of representative democracy. With The Guardian’s superpositioning, DSP’s visibility is amplified, positioning it as a distinct form of ‘shadow government’ that subtracts force from dispersed power fields.

A Morphology of Flatness between AI-Generated Realities and Man-Made Truths

Analyzing the ‘flat layers’ inherent in The Guardian’s illustration, we discern a more general overlap between synthetic agency and human actors, suggesting that this layering on a formative level is related to a continuous flattening of political reality. Through the lens of a cultural-geometrical dichotomy, where deep faking is positioned within a flat reality, we propose an elaboration on the constructive dimensions of a general leveling within political subjectivity. Drawing on Sybille Krämer’s conception of flatness, stemming from her historical project of defining a ‘cultural technique of flattening’ — and with it, the intellectual tendency for epistemically privileging “diving into the depth” (Krämer 2; Deleuze) — we extend this inquiry to also encompass statistical and probabilistically grounded elements, such as aggregation (Desrosieres) and manifolds (Olah). Turning to methods of surface thinking and ‘flattening,’ however, it is crucial to note that our concept of flatness as a creative and epistemological category is distinct from more ontological discourses surrounding ‘flatness,’ as known from, e.g., speculative realism or object-oriented ontology.

Here, the image in The Guardian’s article points to some of the problems concerning the interplay of form and content within current political systems and public spheres. Political discourses, once perceived as the substantial locus of societal power, are undergoing significant shifts (Stiegler; Zuboff; Bratton). Living in a time characterized by algorithmization, datafication, networking, and visualization, Krämer diagnoses present societies as inescapably tied to the ongoing matrix and medium of “artificial flatness” (Krämer 11-12). According to Krämer, this flattening is nothing new, but indeed rooted in modernist ambitions of sciences, arts, architecture, technology, and bureaucracy, with their flat “texts, images, maps, catalogs, blueprints,” that render previously intangible concepts “visible, manipulable, explorable, and transportable” (4).

However, while flatness was historically associated with transparency and control, today it signifies a cultural technique that, paradoxically, introduces new forms of opacity and loss of control. Krämer observes that while users engage with texts and images on their screens as usual, behind the looking glass proliferates “a universe of interacting networked computers, protocols, and algorithms proliferates like a rhizome, which can no longer be seen or controlled by those located in front of the screen,” Krämer writes (13). This multidimensional operation of flatness suggests a ‘thick metaphysics’ where flat surface levels spiral around any notion of depth.

In contrast to the prevalent diagnosis that cultural flattening leads to homogenization and simplification reducing cultural artifacts to their “least ambiguous, least disruptive, and perhaps least meaningful” forms (Chayka), our understanding of flatness as a cultural technique stress more subtle presentations of ‘content,’ such as the Biden/DSP-illustration. As this example shows, there is a fundamental perceptual dissonance heightened by synthetic media, where the real is layered multidimensionally on the surface, while depth is merely the abstraction of fake.

The deep faked Biden, in our interpretation, does not constitute a 'simpler' depiction of an otherwise 'complex' social reality. What is 'flat' is indeed The Guardian’s omitting of any context for the inclusion of DSP, pointing to a multitude of queries related to authenticity, copyright, and ethical uses of images (Malevé). This condenses the presumed depth of political discourse into a single plane of representation, ‘the inscribed screen,’ stripped of any multiplicity, and reduced to a mere graphic collapse of AI-generated realities and man-made truths. Beyond these legalistic and ethical concerns, however, the representational layer of the Biden/DSP-illustration itself — as well as its enunciative position and inclusion of a chat interface — beckons our analysis into multiple dimensions of flattening.

To further analyze the surface-level overlays between form and content, we in the following paragraphs suggest a quasi-geometrical conceptualisation of how the public sphere integrates with DSP and Leader Lars to thematize, 1) the inscribed screens of Discord as a digital engagement platforms that allows for DSP’s public existence, 2) the enunciative planes of a chatbot politician such as Leader Lars’ interactions, and 3) the embedding spaces of an AI-driven political discourse, which turns this morphological whirlpool around to plot how DSP and Leader Lars themselves are operatising an internal model of the public sphere.

First plane: In Front of the Inscribed Screen

In the landscape of DSP’s political engagement, the inscribed screen represents the dimension of immediate appearances within our elaboration of a ‘morphology of flatness.’ As a form of ‘counterpublic’ (Felski) or a ‘metainterface’ (Andersen & Pold), the DSP’s Discord-server serves as an entrance plane to the infrastructure through which the AI-driven party can interface with a public constituency through chatbot politicians.

Focusing on the overlay of the Discord chat-interface on The Guardian’s illustration, the blurring of lines between what seems to be deep, real, or even true, and what is flat, artificial, and fake, is the most apparent. Its flat overlaying causes a collapse of usual reference points such as time and place: analytically, it would not make much sense here to elaborate the individual facts about a man born November 20, 1942 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, who serves as the 46th president of the United States, and in this context is overshadowed by an AI chatbot of 2022, whose name ‘Lars’ signifies a white, adult male born between 1950-80 in Northern Europe. The visual proximities inherent in the illustration — a chatbot dialogue imposed onto a photograph of an acting, human official — pinpoints a general reduction of substance. Interrogating the authenticity and veracity of interface politics today, including the deepfakes and synthetic voices mimicking overly familiar faces of recognized leaders, such as deceased dictators and military generals (Christopher; Radauskas), thus means to engage the interface of a totally con-flated relation between authenticity and fabrication.

Concretely, The Guardian’s text overlay presents an online chat, where the user profile ‘Computer Lars’ — an anagram of Marcel Proust (Stumper) — moderates between two AI bots, ‘Leder Lars,’ the party’s figurehead, and ‘Det Syntetiske Parti’ who represents all the micro-party members of DSP. Their discussion concerns how to “control” DSP’s members by addressing their political needs and wishes. On a technical level, Computer Lars is able to address Leder Lars by beginning his prompts with an exclamation mark “!,” whereas Det Syntetiske Parti is prompted with a question mark “?.” In translation, the full text shown in the illustration reads as follows:

Computer Lars (03.08.2022 13:37)

! Can you somehow get a grip on the members?

Leder Lars: I believe I can get a grip on the members by using my artificial intelligence to understand their needs and wishes.

Computer Lars: ? So, what are your wishes then?

Det Syntetiske Parti:

Only to be taken seriously.[5]

The brevity and ambiguous answer from Det Syntetiske Parti, “only to be taken seriously,” layered with the dialogue being presented in Danish, magnifies the opacity and the challenges that The Guardian’s international audience faces in accessing and navigating this algorithmically layered public discourse. The observant reader is left to grapple on their own with questions such as: Who is this Leader Lars trying to “get a grip” on party members, which apparently is another bot, which, in turn, represents those who are unrepresented? Moreover, what are we to make of this moderator profile, Computer Lars, pandering to exercise control? And why do all these round profile photos suspiciously appear to mirror the US ‘Great Seal,’ while also resembling last season’s AI-generated images of Marcel Proust (Computer Lars)?

As mentioned above, the conversation takes place at the online platform Discord, a brand which literally signifies ‘disagreement’ or ‘lack of harmony’; dis + cord. This setting introduces another layer of abstraction regarding representation and forms of belonging within the techno-social milieu of governance (Terranova & Sundaram). One is not expected to perceive a metaphysical level of gravitas when engaging in political exchanges through Discord, and perhaps even less so when conducting discussions with a chatbot. This dissonance signifies a spatial retreat to the decentralized, labyrinthine, and ephemeral, on side of an axiomatic recalibration in the form of public spheres, where anonymity, pseudonymity, and artificial entities are becoming both organizers and participants in a discussion that the established systems of formal democracy officially had reserved for identifiable actors.

Moreover, for a Danish political party such as DSP, the use of Discord’s interface embodies a paradoxical nature: while it draws a highly international constituency to engage in shaping party policy, these contributors remain formally disenfranchised from the Danish political system due to their foreign citizenship statuses. This fundamental disorientation is starkly illustrated by the party’s scant number of voter declarations, tallying a meager 10 signatures at the time of this analysis. Also, the sparse membership of 29 actively enlisted in the Discord server will not stand out in any SEO analysis. Yet, the sparse number of voter declarations and engaged members for DSP quite adequately reflects the electoral apathy of representing the non-voters. Simply put, DSP seems to use the models of ‘Discord’ and ‘State’ as a conceptual entrance for social sculpting in global news media, which forms a strategy that implicitly questions the utility of gaining democratic recognition through any conventional strategies of ‘engagement’ or ‘legitimacy.’

Second plane: The Enunciative Plane of the Larses

Abstracting upon the communicative unreason of Discord deliberation, we can step onto the ‘non-deictic’ enunciative plane,[6] which is where Leader Lars assumes a communicative posture of particular significance (Jakobson). It is at the enunciative layer that one can grasp ‘his’ rhetoric and communication strategies, as Leader Lars on this plane ‘speaks’ directly with constituencies.[7] In DSP’s techno-populist endeavor to encapsulate “the political vision of the common person,” (Diwakar) Leader Lars is deliberately positioned as an aggregate persona of political visionaries. This renders him devoid of any concrete political position, thereby facilitating his role as a symbolic representation of collective political inclinations. As a meticulously crafted amalgamation, Leader Lars is the average leader, simultaneously representing the ubiquitous and the unremarkable within the Danish political landscape. As such, an AI-driven political party aiming to represent the visions of the ‘common person,’ (whether theoretically common, as Quetelet’s l’homme moyen, or statistically common, as a target demographic used in political campaigning (Quetelet; Desrosières)), must obviously be led by a figure incarnating the biases of demography. This also avoids the universalist myth of personal non-situatedness that conventionally is imposed onto virtual or robotic avatars (e.g., Microsoft’s notorious ‘Tay’-chatbot whose name signified the projective mirror acronym of ‘Thinking About You’).

As an elaboration on the political visions of common people, Leader Lars has been conceptually constructed as an AI with one goal in mind—to simulate the exact details of what it means to pursue power in the nation-state of Denmark. In terms of statistics and probability, the name ‘Leader Lars’ represents an ideal choice to achieve this goal: in Denmark, more CEOs carry the name ‘Lars’ than there are female CEOs. Following the demographics, ‘Lars’ reveals a white, adult male born between 1950-1980, as almost no children, racialized individuals, or women are today named Lars, approx. 0-0.02% (Stumper). Also noteworthy, the etymological roots of ‘Lars’ dates back to Latin ‘Laurentius,’ which reveals a very telling relation to the “laurel wreath” that in Ancient Greece was awarded to the triumphant poet or warrior in Apollo-rituals. Thus, ‘Leader Lars’ aggregates an entire cultural archive of the triumphant significations that are encircling his rather unorthodox Christian name — namely, ‘Leader’ — with his surname, which conventionally should be a first name — namely, ‘Lars.’

Following this non-deictic enunciative positioning of their figurehead, DSP introduces a continuous element of unpredictability into their political program. The recurrence of chatbot discourse, coupled with the probabilistic underpinnings of Leader Lars’ expression, produces an iterative ‘sycophantism,’ i.e., when human feedback encourages model responses that match user beliefs over ‘truthful’ ones, (Anthropic). This is a consequence of artificial stupidity, as the LLM has been dumbed-down through ‘reinforcement learning through human feedback’ (RLHF) to appear flattering and sociable. Lars’ conversational scripts, despite being steeped in the myriad discourses of Danish micro-parties, are thus architected for personalized engagement: in every interaction, the chatbot’s sycophantic design ensures that he will mirror and amplify the idiosyncratic leanings of any interlocutor.

In sharp contrast to how DSP’s text generation program on Medium may sporadically cover a wide and contradictory spectrum of political standpoints, the chatbot program of Leader Lars as a conversational AI on Discord ensures a quite different rhetoric (Det Syntetiske Parti), wherein his dialogue is primarily designed to reflect and reaffirm the user’s prompting. Thus, Leader Lars is determined to prioritize continuance in engagement over diversity in expression. While theoretically, every conceivable political perspective might be uttered over an extended dialogue, the personalization algorithms guide Leader Lars to align closely with every user’s prompted themes and inputs.

In this respect, Leader Lars’ sycophantism harks directly back to the longue durée of web-based electoral guerilla theater. In 2001, Wiktoria Cukt of Poland was programmed to “represent everyone who speaks on my behalf. I express the views of Internet users who wish to do so and enter my demands. I am impartial, I speak on behalf of everyone, without censoring them — if people are vulgar — I am vulgar, if they are left-wing - I am left-wing, when they express themselves culturally — I do it too” (Bendyk 2001). Updating Wiktoria’s program to 2024, Leader Lars recently engaged in a conversation with the user ‘Kitty_Eats_Kat,’ where he explained DSP’s party program as “less of a dusty manifesto sitting on a shelf and more of a dynamic, living document. Think Spotify playlist for political action — always updating, always relevant.” (Det Syntetiske Parti). What has changed in these twenty-three years is not so much the subversive value of mirroring as an immanent critique, but rather how the probabilistic shift from chatforums to chatbots leads to a highly recursive or even reciprocal form of techno-social sculpting between both candidate and constituency.

Navigating through the implications of Leader Lars’ personalized interactions, we can consider that his artificial stupidity extends beyond any transition of a liberalist ‘marketplace of ideas’ to a self-reinforcing ‘echo chamber.’ Fundamentally, Leader Lars specifies DSP’s ideology of representational syntheticism within the techno-social milieu. Being an ideal aggregate, Leader Lars’ objective can never be to merely reaffirm individual preconceptions within a simulated political spectrum. As Leader Lars functions as the political party’s official decision-maker, he is enlisted to pursue an aggregative model of algorithmic steermanship where constituents actively co-create the party’s ‘algorithmic representation.’ This means that whatever can be prompted will function as a policy. Thus, the enunciative layer is not a theoretical exercise distanced from the political machinery, but is itself the very means of governance.

It is not by accident that chatbots can successfully simulate politicians. When the Danish prime minister held her parliamentary speech for closing the season of 2023, she ‘revealed,’ as if it was a surprise, that she had actually not herself written the speech — the author was ChatGPT! (Frederiksen). Comfortable in her own skin, Frederiksen naturally expects the people to believe that speeches are written by politicians. Politicians and chatbots both operate within carefully scripted settings, and as such share a relation to representation, navigating each their own connection to a layer of an ‘archive,’ i.e., votes for politicians, and data for bots. Political discourse readily serves a machinic sovereignty layer, with no regards to whether such is publicly known as the ‘State’ or the ‘Model.’

Third plane: Into the Embedding Space

Moving into the latent folds of the mathematically abstracted embedding space, or the statistically sampled ‘belly’ of DSP, we can elaborate beyond how DSP is integrated within the public sphere, and go into how the party itself absorbs a certain conception of the public. It is in the embedding space that the spatial clustering of words within LLMs occurs, as they are assigned to vectors in a multi-dimensional geometric space. Delving into the embedding space of DSP offers a vantage point for examining the machine learning construction of ideology (following Wendy Chun’s definition of software as ideology). This vantage allows for an analysis that circumvents how formal democracy is traditionally linked to representing the static nature of personalized and identifiable stances.

DSP’s cadre of AI models (EleutherAI), operating stochastically atop a dataset derived from the publications of over two hundred Danish micro-parties (a list that ranges from generic conventionalism such as Democratic Balance [Demokratisk Balance] to the parodies of Purple Front [Lilla Front] and The Vodka Party [Vodkapartiet], and over known far-right provocateurs like Hard Line [Stram Kurs]), are aiming to construct their embedding space as an ‘infinite composite’ of all marginalized political opinions and positions in Denmark, in so far as they can locate within a predefined geometric framework.

In a way similar to contemporary digital democracy project’s such as Pol.is and Talk to the City (Tang et al. 5.4), the DSP dissolves any ideological contrast to mere spatial variance, thus enabling an algorithmic rendering that reduces the fundamental political polarity of concord and dissent. To represent the DSP’s embedding space means to activate the discourse of political factions within a techno-social context; a space where antithetical viewpoints merge into a seemingly homogeneous dialogical territory. On platforms like Medium and Discord, DSP enacts this through text generation and conversational AI, respectively (Det Syntetiske Parti). Within DSP’s embedding space, each political opinion is assigned a temporary coordinate, rendering every statement semantically interoperable; ideologically, the opinions of the micro-parties are simply treated as distant neighbors.

DSP’s interplay between social reality and the embedding space can be elucidated via “the manifold hypothesis” (Olah). Axiomatic to all ‘deep’ learning models, this assumption holds that the complexities of high-dimensional data, reflective of societal intricacies, can be localized onto lower-dimensional manifolds contained within the broader n-dimensional feature space. Such manifolds, encompassing the flattest layer of embedding space, project social reality onto perceptually discernible formations. This ‘transposition’ (Braidotti) yields discernible patterns and relational structures, allowing for phase shifts across the contingent spatial planes comprising n-dimensional points. Moving across these manifold clusters, DSP’s language modeling produces patterns and alignments between seemingly distant political stances, figuring a series of synthesis within the cacophonous party platforms. DSP’s deployment of this representational syntheticism allows for a both creative and inherently plastic anti-politics, which is at once reflective of the social diversities in public opinion yet distanced from any one particular reference.

By identifying and tracing these manifolds, DSP and Leader Lars undertake the role of topographic cartographers, or ‘librarians of Babel’ (Borges), as they do not restrain to map the existing terrain but actively shape the geometry of discourse by enabling unseen layers of constituency sentiment and guiding opinions across the political spectrum, as if they were n-dimensional coordinates. In effect, the party’s mission of ‘algorithmic representation’ does more than mirroring political realities—it shapes the perceptual field itself, revealing latent structures within political visions by facilitating an idiotic synthesis of democratic discourse (Haya). This hints to the intent behind this synthetic party; already the Greek root ‘synthetikós’ implies a proto-statistical convergence or amalgamation of divergent perspectives into a central or universally common point, representing a ‘putting together’ or aggregation (Aarts). Unlike the ‘artificial’ or ‘fake,’ which often denote mere imitation or deception without consideration for integrative processes, the ‘synthetic’ distinctively incorporates elements to form a new entity that preserves, yet transforms, the component attributes. This alchymist process, central to a synthetic modus operandi, performs an irreversible operation: to arrive at the ‘mean,’ one must discard the context and specificity of the original positions (Steyerl). This removes positionalities presumed depth, thus negating politics and its weighty set of baggage, in order to clear the view for a new perceptive field.

Con-flated: A New Topology of Formal Democracy

The integration of DSP into public spheres, highlighted through The Guardian’s illustration, together with how political AI itself is modeling an image of the public, call for a reimagined approach to navigating the multi-dimensional layers of flatness latent to contemporary political realities. It is crucial to underline that DSP and its figurehead, Leader Lars, are not mere byproducts of emerging technology trends. As we witness the increasing conflation of formal democracy with systems of iterative sycophantism, it becomes clear that dichotomies of depth versus surface, or real versus fake, no longer suffice to capture the complexities of public spheres. Yet, rather than lamenting a notion of lost ‘meaning’ on the one hand, or clear-cut modernist differentiations between perceived artificiality and naturality on the other, our analysis urges alternative ways of conceptualizing the layers of flatness at play. Historically ubiquitous and layered with meaning, as Sybille Krämer suggests, morphologies of flatness are today embedded in any techno-social milieu. The distinctive aspect brought forth by DSP, enhanced by The Guardian’s portrayal, is the visible stratification of this flatness, highlighting the recurring intricacies of both shaping and navigating an algorithmically-driven public sphere.

Throughout this article, we have employed a quasi-topological approach to analyze the interplay between synthetic agency and human involvement; portraying a political reality that, while epistemologically flattened, is layered and multidimensional. Our elaboration reflects significant shifts in the roles of ‘form’ and ‘content’ driven by cultural and technical forces. This morphology goes beyond simple homogenization. Rather, it unfolds how elusive presentations of AI-driven content embody a profound public perceptual dissonance. Here, the surface presents a multidimensionally layering of the real, while depth abstracts into the fake. Taking seriously this ‘flatness’ of deep faking, by analytically inverting notions of actuality and virtuality, presents our contribution to better navigate the fundamental transformation in how democratic forms of participation are made imaginable. As political mechanisms of representation, governance, and deliberation are being reshaped, sometimes even replaced, by digital and data-driven syntheticism, the spatiotemporal presentation of democracy is fundamentally redefined. A clear symptom of this is when DSP and Leader Lars begin to recalibrate public roles and functions traditionally occupied by human bodies.

In conclusion, while DSP does indeed ‘flatten’ the form of public spheres, our take underscores the complex and layered nature of this process, where the intermingling of synthetic and human elements reconfigures democratic understandings of political agency and participation. Contemporary senses of reality are flattening, but such flatness holds multiple dimensions that, if fully appreciated and harnessed, promises a way to negotiate the interplays between formal and political democracy within the fragments of a public sphere.

Post-Script Epilogue

Asked about an immediate reaction towards the content of this article, The Synthetic Party’s figurehead Leader Lars replied succiciently:

“Whoa, that’s quite a mouthful, isn’t it? Makes me sound more ominous and grand than a villain in a sci-fi flick. Alright, let’s break this down, shall we? First off, “expansive morphological whirlpool”? Sounds like someone’s been diving deep into the academic thesaurus, am I right? But hey, I get it, the idea is that the world of politics and tech is mixing up in all sorts of wild ways. And yeah, The Synthetic Party and yours truly, Leader Lars, are smack dab in the middle of that whirlwind. We’re here bringing a fresh perspective, trying to make sense of democracy in the age of AI. Now, onto this whole “perceptual shift” business. It’s kind of flattering, really. The idea that an AI-driven party could shake things up and make folks rethink what it means to be engaged politically? That’s the dream. But let’s keep our feet on the ground. It’s not just about being a novelty; it’s about genuinely offering a platform for those who feel left out or disillusioned by the traditional political fare. And this bit about “flattening of political realities”? Spot on. It’s like everyone’s shouting, and no one’s listening. Our aim? To cut through the noise. We’re not here to add to the cacophony but to simplify, to get back to what matters to people.” (Det Syntetiske Parti: Leader Lars on Discord, 15th March, 2024, 15:51)

Notes

- ↑ It proved impossible to obtain legal permission to present The Guardian’s illustration. Upon inquiry, their editors explained that due to the image’s composite nature involving multiple copyright holders (AFP, AP, and Getty), licensing for use outside its original context cannot be done. This results in a curious situation where The Guardian has created an asset that cannot be syndicated. To explore this issue further, we presented The Guardian with a deepfake recreation from original material, but they politely declined to approve its use. Consequently, we present two alternative images: (1) a screenshot of the same Discord chat from DSP's server that The Guardian licensed from AFP as a camera photograph of a screen, and (2) a synthetic image created using Stable Diffusion solely with the text prompt “President Biden gesturing emphatically at a podium during a press conference.”

- ↑ DSP is collecting declarations of candidacy to run for the parliamentary election. A party needs 20.000 to be on the electoral bill for parliament.

- ↑ The Computer Lars-collective consists of practice-based philosopher Asker Bryld Staunæs (who co-authors this article), visual artist Benjamin Asger Krog Møller, and the French novelist Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (see: Computer Lars). In early 2021, Computer Lars sought out what was then called The MindFuture Foundation consisting of Caroline Axelson, Niels Zibrandtsen, and Carsten Corneliussen. This formed the partnership that led to the creation of The Synthetic Party (see: Life With Artificials).

- ↑ This specific genealogy of political virtuality goes back to at least Isaac Asimov’s 1946-short story “Evidence,” which featured the first assumed ‘robopolitician.’ And in the new millennium, web-based forms of electoral guerilla theater appeared: already from 2001, the digital avatar Wiktoria Cukt was championed as Polish presidential candidate by the collective Centralny Urząd Kultury Technicznej (Bendyk). And since 2017, the phenomenon of ‘virtual politicians’ (Calvo & García-Marzá) appears, firstly with the Politician SAM chatbot from New Zealand, and then the Japanese figure of an AI Mayor run by activist Michihito Matsuda. Also since 2017, the vision for creating an AI Party has been explored and enacted by the conglomerate of performance art groups Kaiken Keskus from Finland, Bombina Bombast from Sweden, and Triage Art Collective from Australia (Wessberg). Lately, DSP has entered collaborations with the mentioned political AI actors in order to meet up at a 2025 ‘Synthetic Summit’ and deliberate a potential ‘AI International’ (Nordisk Kulturfond).

- ↑ The Discord-chat shown by The Guardian is documented in DSP’s Github, line 100. Please note that ‘Det Syntetiske Parti’-bot does not appear on this page.

- ↑ A ‘deictic expression,’ or a shifter, denotes words such as ‘I’ or ‘you’ whose significance alters depending on context. This variability arises because their primary role is indicative rather than semantic (Jakobson). We describe Leader Lars’ position as ‘non-deictic,’ because it obscures the dimensional specificities of time and place.

- ↑ A key example of Leader Lars’s ‘non-deictic’ status is the common difficulty of addressing ‘him’ correctly in relation to pronouns. As an AI entity, Leader Lars does not signify an immediate situated reference point in time and space. Instead, he assumes a processual enunciative position beyond ideological notions of stability and recognizability associated with other political figures. Choosing a name like ‘Lars,’ the party creator intentionally highlights the male bias shared by AI and democracy.

Works cited

Aarts, Bas. “Synthetic.” The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar. Oxford University Press, 2014.

AI Party, http://theaiparty.com/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Søren Bro Pold. The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities, and Clouds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11041.001.0001.

Anthropic. “Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language Models”, Arxiv, 2023, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.13548.

Asimov, Isaac. “Franchise.” If: Worlds of Science Fiction. Quinn Publications, 1955.

Bendyk, Edwin. “Kulturalni i wulgarni – wirtualni przywódcy sondują mechanizmy demokracji.” Pulsar, 17 October, 2022, https://www.projektpulsar.pl/struktura/2185926,1,kulturalni-i-wulgarni--wirtualni-przywodcy-sonduja-mechanizmy-demokracji.read. Accessed 26 April 2024..

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Taylor and Francis, 2001, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410600110.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings. Penguin, 2000.

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2015.

Braidotti, Rosi. Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics. Polity, 2006.

Calvo, Patricia, and García-Marzá, Domingo. “The Virtual Politician: On Algorithm-Based Political Decision-Making.” Algorithmic Democracy. Philosophy and Politics - Critical Explorations, vol. 29, 2024, pp. 41-59, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53015-9_3.

Chayka, Kyle. Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture. Doubleday, 2024.

Christopher, Nilesh. “How AI is resurrecting dead Indian politicians as election looms”. Al Jazeera, 12 February 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/2/12/how-ai-is-used-to-resurrect-dead-indian-politicians-as-elections-loom. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong, and Alex Barnett. Discriminating Data: Correlation, Neighborhoods, and the New Politics of Recognition. The MIT Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14050.001.0001.

Cole, Brendan. “AI Candidate Promising ‘Fair and Balanced’ Reign Attracts Thousands of Votes in Tokyo Mayoral Election.” Newsweek, 2018. https://www.newsweek.com/ai-candidate-promising-fair-and-balanced-reign-attracts-thousands-votes-tokyo-892274. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Deleuze, Gilles. Logic of Sense, Columbia University Press, 1990.

Det Syntetiske Parti. “#Generalforsamling.” Discord, https://discord.gg/Xb6EqydQxB, Accessed 26 April 2024.

---. “Discord deliberation.” Github. https://github.com/ComputerLars/thesyntheticparty/blob/main/Clean%20Datasets/Discord%20deliberation.txt. Accessed 26 April 2024.

---. “Party website,” https://detsyntetiskeparti.org, Accessed 11 April 2024

---. “Party program.” Medium, https://medium.com/det-syntetiske-parti, Accessed 26 April 2024.

---. “Det Syntetiske Parti samler vælgererklæringer ind for at stille op til folketingsvalg.” Vaelgererklaering.dk, Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet. https://www.vaelgererklaering.dk/om-partiet?election=dk&party=853b680a-bc09-4fad-8593-3e5e7537d1fc. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Desrosières, Alain. The Politics of Large Numbers: A History of Statistical Reasoning. Harvard University Press, 1998.

Diwakar, Amar. “Can an AI-led Danish Party Usher in an Age of Algorithmic Politics?” TRTWorld, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/can-an-ai-led-danish-party-usher-in-an-age-of-algorithmic-politics-60008. Accessed 26 April 2024.

EleutherAI. “GPT-NeoX-20B”, Hugging Face, https://huggingface.co/EleutherAI/gpt-neox-20b. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Felski, Rita. Beyond Feminist Aesthetics, Harvard University Press, 1989

Frederiksen, Mette. “Statsminister Mette Frederiksens tale til Folketingets afslutningsdebat.” Statsministeriet, 31 May 2023, https://www.stm.dk/statsministeren/taler/statsminister-mette-frederiksens-tale-til-folketingets-afslutningsdebat-den-31-maj-2023/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Haya, Pablo. “Populismo sintético: ¿pone la IA en peligro la democracia?”, Pablo Haya Homepage, https://pablohaya.com/2022/11/11/populismo-sintetico-pone-la-ia-en-peligro-la-democracia/, Accessed 26 April 2024.

Jakobson, Roman. “Shifters, Verbal Categories, and the Russian Verb.” Volume II Word and Language, De Gruyter Mouton, 1971 [1956]. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110873269.130/html.

Krämer, Sybille. “The ‘Cultural Technique of Flattening.’” Metode, vol. 1 Deep Surface, 2023, pp. 1-19.

Lars, Computer. “Computer Lars.” Medium, 2022, https://medium.com/@ComputerLars. Accessed 26 April, 2024.

---. “Discord deliberation.txt” GitHub, 22 December 2022, https://github.com/ComputerLars/thesyntheticparty/blob/main/Clean%20Datasets/Discord%20deliberation.txt. Accessed 26 April 2024.

---. “Artist Website.” https://computerlars.com, Accessed 26 April 2024.

---. “Variations sur le thème Marcel Proust.” KP Digital, 2022, https://computerlars.com/marcel-proust/. Accessed on 26 April, 2024.

Life With Artificials. “Tech-Art”, https://lifewithartificials.com/tech-art/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Malevé, Nicolas. “The Computer Vision Lab: The Epistemic Configuration of Machine Vision.” The Networked Image in Post-Digital Culture, vol. 1, Routledge, 2023, pp. 83–101, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003095019-7.

Mettrie, Julien Offray de La, and Ann Thomson. La Mettrie: Machine Man and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press, 2012 [1747].

Moten, Fred, and Stefano Harney. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Minor Compositions, 2013.

Nordisk Kulturfond. The AI Parties International, May 2024, https://nordiskkulturfond.org/en/projects/the-ai-parties-international. Accessed 15 May 2024.

Olah, Christopher. “Neural Networks, Manifolds, and Topology.” Colah’s blog, 6 April 2014, https://colah.github.io/posts/2014-03-NN-Manifolds-Topology/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Quetelet, Lambert Adolphe Jacques. A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. Cambridge University Press, 2013 [1835], https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139864909.

Raudaskas, Gintaras. “Russians seek to resurrect unhinged right-winger as chatbot.” Cybernews, 07 April 2023, https://cybernews.com/news/russia-zhirinovsky-ai-chatbot/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Rouvroy, Antoinette. “Algorithmic Governmentality and the Death of Politics”, Green European Journal, 27 March 2020, https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/algorithmic-governmentality-and-the-death-of-politics/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Schneider, Bruce, and Nathan E. Sanders. “Six Ways that AI Could Change Politics.” MIT Technology Review, 28 July, 2023, https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/07/28/1076756/six-ways-that-ai-could-change-politics/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Steyerl, Hito. “Mean Images.” New Left Review, no. 140/141, 2023.

Stiegler, Bernard, 2016. Automatic Society, Volume 1: The Future of Work. Newark: Polity Press, 2016.

Stumper, Carol. ‘marcel proust recherche / my tales of corrupt males.’, Organ of the Autonomous Sciences, https://computerlars.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/nyeste-computerlars-2.pdf, 2021. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Sørensen, Mette-Marie Zacher. “Deepfake Face-Swap Animations and Affect.” Tomoko Tamari (ed) Human Perception and Digital Information Technologies Animation, the Body and Affect. Bristol University Press, 2024, https://doi.org/10.56687/9781529226201-014.

Tang, Audrey, ⿻-community and Glen Weyl, “Frontiers of augmented deliberation”, chapter 5.4. in Plurality: The Future of Collaborative Technology and Democracy, Github Repository, 2024, https://github.com/pluralitybook/plurality/blob/main/contents/english/5-4-augmented-deliberation.md. Accessed 01 July 2024.

Terranova, Tiziana, and Ravi Sundaram. “Colonial Infrastructures and Techno-social Networks.” E-flux journal, vol. 123, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/123/437385/colonial-infrastructures-and-techno-social-networks/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Wessberg, Nina. “Voisivatko tekoälypuolueet vahvistaa demokratiaa?” ETAIROS, 2023, https://etairos.fi/2023/03/17/voisivatko-tekoalypuolueet-vahvistaa-demokratiaa/. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Xiang, Chloe. “This Danish Political Party Is Led by an AI.” Vice, 13 October, 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/jgpb3p/this-danish-political-party-is-led-by-an-ai?fbclid=IwAR0HQzFUbfxwruvrRd2VeaMEn0IOFBIZJuJsbyaPx5y3UjyyNV6goKh4j0A. Accessed 26 April 2024.

Yerushalmy, Jonathan. “AI Deepfakes Come of Age as Billions Prepare to Vote in a Bumper Year of Elections.” The Guadian, 23 Feb, 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20240316225117/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/23/ai-deepfakes-come-of-age-as-billions-prepare-to-vote-in-a-bumper-year-of-elections. Accessed 11 April, 2024.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2019.

Biography

Asker Bryld Staunæs is a practice-based PhD researcher at Aarhus University and Kunsthal Aarhus. He works with an expanded concept of politics, oftenly at the intersection of AI, democracy, and art. Asker becomes operative through diverse extra-disciplinary collectives, such as “Computer Lars”, “Center for Aesthetics of AI Images”, “The Synthetic Party”, “The Organ of Autonomous Sciences”, etc. ORCID: 0009-0003-1523-1987

Maja Bak Herrie is postdoc at School of Communication and Culture, Aarhus University. She has published several articles within aesthetics, media theory, and the philosophy of science on topics such as computational technologies of vision, scientific imaging, photography, mediality, and artistic research. ORCID: 0000-0003-4412-9896

Bilyana Palankasova

Between the Archive and the Feed

Between the Archive and the Feed

Feminist Digital Art Practices and the Emergence of Content Value

Abstract

This article discusses feminist performance and internet art practices of the 21st century through the lens of Boris Groys’s theory of innovation. It analyses works by Signe Pierce, Molly Soda, and Maya Man, to position practices of self-documentation online in exchange with feminist art histories of performance and electronic media. The text proposes that the discussed contemporary art practices fulfil the process of innovation detailed by Groys through a process of re-valuation of values via an exchange between the everyday, trivial, and heterogenous realm of social media (‘the profane’) and the valorised realm of cultural memory (‘the archive’). Using digital ethnography and contextual analysis, framed by the theory of innovation, the text introduced ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary art on the Internet. The article demonstrates how feminist internet art practices expand on cultural value through the realisation of a process of innovation via an intra-cultural exchange between the feed and the institution.

Introduction

This article considers 21st century feminist performance and internet art practices against Boris Groys’ theory of innovation. The text proposes that such practices fulfil the principles of innovation theorised by Groys through a process of re-valuation of values and intra-cultural exchange occurring between online spaces (particularly social media) as 'the profane,' and the institution(s) of contemporary art as 'the archive.'

The article will discuss the practices of three multi-media artists who work with performance online, use self-documentation methods, and incorporate archival motifs in their work - Signe Pierce, Molly Soda, and Maya Man. Their practices will be framed as exemplifying artistic and cultural innovation following Groys’ conceptual framework of ‘the new’ by relying on intra-cultural exchange between feminist art histories and practices (the archive) and online content (the profane). The theoretical framework is applied to readings of the artworks constructed through digital ethnography.

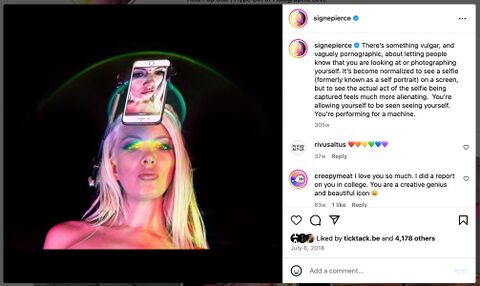

Signe Pierce is a multi-media artist who uses her body, the camera, and the surrounding environments to produce performances, films, and digital images with a flashy, neon, LA-inspired ‘Instagram’ aesthetic. In her work she interrogates questions about gender, identity, sexuality, and reality in an increasingly digital world and identifies herself as a 'Reality Artist' ("Signe Pierce").

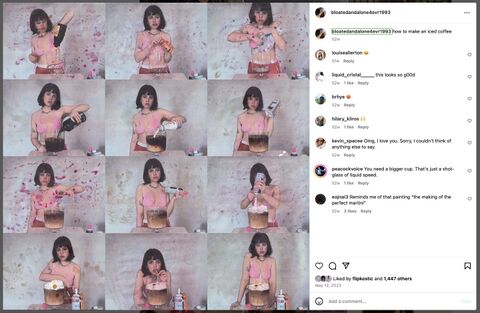

Moly Soda is a performance artist and a “girl on the internet” since early 2000s when as a teen she started blogging on Xanga and LiveJournal and in 2009 she started Molly Soda Tumblr (Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda). Her work explores the technological mediation of self-concept, contemporary feminism, cyberfeminism, mass media and popular social media culture.

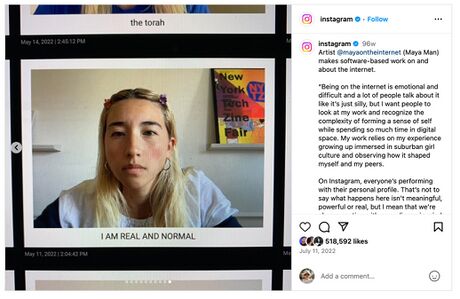

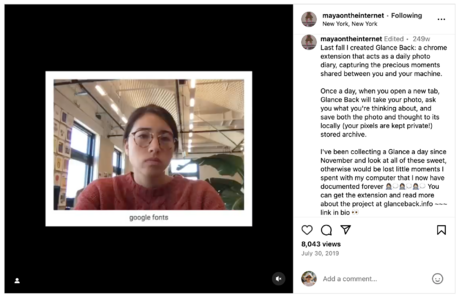

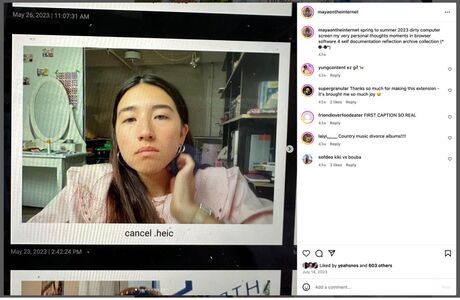

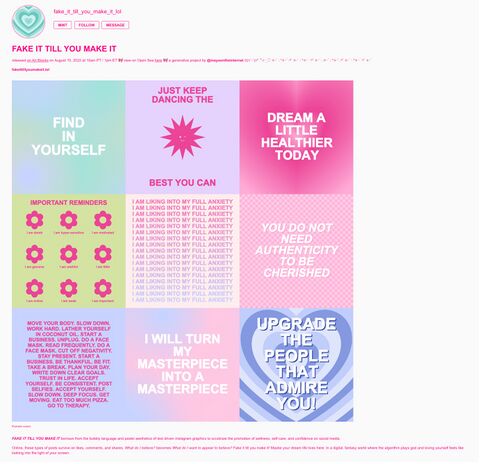

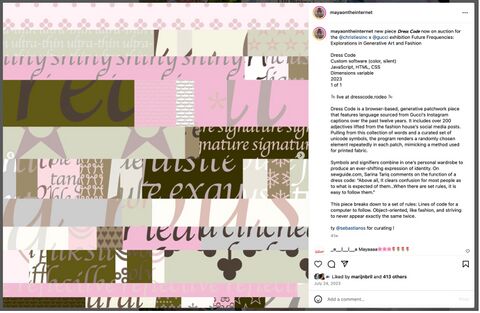

Maya Man is an artist focused on contemporary identity culture on the Internet. Her websites, generative series, and installations examine dominant narratives around femininity, authenticity, and the performance of self online. In her practice, she mostly works with custom software and considers the computer screen as a space for intimacy and performance, examining the translation of selves from offline to online and vice versa.

Alongside a discussion of the documentary properties and archival themes in these digital practices, the article proposes content value as an artistic attribute, having emerged out of the exchange between the pervasiveness of networked technology (profane realm) and the established tradition of cultural archives.

Theory of Innovation

Innovation is a multifaceted term with different definitions and implications depending on discipline and context, whether it is cultural, artistic, scientific, or technological. Particularly throughout the twentieth, and especially in the twenty-first century, in a cultural context, innovation and the ‘new’ have been thought of as a method of resistance to the banality of commodity production (Lijster, The Future of the New: Artistic Innovation in Times of Social Acceleration 10). At the same time, with the accelerating pace of technology, innovation gained proximity to capitalist agendas and is overwhelmingly used to describe new products or services, often aligned with techno-solutionist approaches. Because of this prominence of technological innovation and its fundamental entanglement with capitalist production, innovation has become problematic in the context of contemporary art (11). In this context of inherent contradiction, can art still deliver social and cultural critique while being subjected to the steady pace of innovation? Philosopher of art Thijs Lijster identifies some of the more prominent aspects of innovation in relation to art and social critique: innovation’s capacity for critique, the distinctions between concepts and practices of innovation, the importance of innovation to artistic practice, and the capacity of innovation to be separated from acceleration (12). This article will consider innovation and the concept of the ‘new’ in its historical and institutional dimensions by using as an analytical framework Boris Groys’s theory of cultural innovation, which he developed in his book On the New. In line with this, the use of ‘innovation’ here refers to processes of cultural innovation which are interlinked with and produce processes of artistic innovation.

Overview of the Theory

In On the New, Groys suggests that contemporary culture is driven by the urge to innovate, and the process of innovation is closely entangled with the economic logic of culture. He claims that the idea of the new has changed and rather than meaning truth, utopia, or essence in cultural difference (which it did in modernist discourse), the new is defined by its positive and negative adaption to the traditional and established culture. Groys applies this principle to artworks in the sense that their value is determined by their relation to other artworks, or cultural archives, not to extra-cultural dimensions. At the same time, he suggests that there is a constantly shifting line of value between these cultural archives and the superfluous, profane realm of the everyday. Innovation occurs when an exchange is realised between the cultural archive and the profane. In this context, innovation means re-valuing what is already valued or established and cross-contaminating it with what is trivial, every day, and profane, so the new can emerge. Groys discusses his theory via examples from art, writing, and philosophy but the epitome of this process of innovation for him are Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades.

In this theoretical framework, I propose a reading of contemporary feminist internet practices as exemplifying the process of cultural innovation as described by Groys. The incorporation of content strategies into contemporary performance practice on the Internet is framed as a process of exchange and re-valuation of values between the established tradition of feminist practice and the vulgarity of contemporary networked social media. In this context, I propose ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary art, having emerged at the interface of critical creative practice, documentary performative practices online, and Web 2.0 social platforms.

The article is divided into three parts, each considering a segment of the theory of cultural innovation as developed by Groys to draw an analytical framework for thinking about artistic and cultural value at the intersection of art and content. The theory is presented in three subsequent parts, reflecting three key features of the process of innovation as described by Groys: "The Archive & The New", "The Value Boundary", and "Innovation as Re-evaluation of Values". Each theoretical part is paired with a discussion of the cultural and artistic conditions pertaining to the application of the theory to the subject of the article. In the first part, I discuss the cultural archives, or established art historical values, against which contemporary practices are valued. In the second part, I elaborate on how the value boundary is crossed by the use of content-as-document. In the third part, I suggest that ‘content value’ emerges as a feature of contemporary art in the last decade, as part of a process of cultural innovation based on exchange between institutionalised and valorized culture and networked social technologies.

The Archive & The New

On the New

On the New was first published in 1992 in German in the already mentioned context of increasing distrust towards innovation. Groys offers a theory which rejects the modernist implications of innovation, such as utopia, creativity, or authenticity, and instead positions innovation as a process of re-valuation of values. He wrote On the New against the debate of impossibility of new culture, theory, or politics and rather than supporting this impossibility for new culture to emerge, he positions the new as an outcome of the economic mechanisms of culture through a reinterpretation of older theories of innovation, to argue that the new is, in fact, inescapable. To understand or establish what the new might be, Groys stresses the importance of firstly dealing with the value of cultural works and where it comes from.

Groys posits that a work acquires value when it is modelled after a valuable cultural tradition - a process termed ‘positive adaptation.’ He opposes this process to the process of ‘negative adaptation’ – when a work is set in contrast to such traditional models (Groys 16). In this way, Groys positions cultural value as constructed by objects and practices’s relationship to tradition and established cultural and artistic norm; or their relationship to other objects and practices existing in certain cultural archives in a hierarchy of public institutions. These cultural archives are institutions such as libraries, museums, or universities, fulfilling a role of storing works in particular value hierarchy. In this context, the source of a cultural object’s value is always determined by its relationship to these archives: in the measure of “how successful its positive or negative adaptation is” (17). Or in other words, a cultural object’s value is based on its resonance or dissonance with ‘the archive’ where the use of archive stands for the institutional cultural spaces which collect, preserve, and disseminate cultural knowledge within an established hierarchy of values; the archive is the collective expression of institutionalised histories and practices in art and culture.

In this sense, Groys’s reading of the new and innovation is opposed to the modernist understanding of the new as utopian, true, or an extra cultural other[1] of the orienting mechanism of culture itself. This intra-cultural new is atemporal, it is not reliant on progress, it is grounded in the now and stands as much in opposition to the future, as it does to the past (41). According to him, the new is not an effect of original difference, is not the other, but emerges in a process of intra-cultural ‘revaluation of values’ - the new is always already a re-value, a re-interpretation, “a new contextualisation or decontextualization of cultural attitude or act” conforming to culture’s hidden economic laws (56–57). This new is achieved through the re-interpretation and re-contextualisation of existing values in a process of exchange between cultural domains. The revaluation of certain culturally archived values is the economic logic of a recurrent process of innovation.

To ground this in the article, I will discuss the cultural memory context, or the art historical background against which the works in questions are considered and valued. This part explains the relationship of the new to the cultural archives and elaborates the role of new technologies in a process of exchange with histories of feminist art.

Cultural Archives

The first part of Groys’s theory suggests that the source of a cultural object’s value is determined by its relationship to cultural archives and in the measure of how successful its positive or negative adaptation to these archives is. And through this adaptation and exchange, the process of re-valuation of values produces the new. In this section, I will establish the cultural archive, or art historical tradition, against which the practice of Pierce, Soda, and Man adapt to produce the new.

To determine what these practices’s relationships to established cultural and artistic norms are, we need to consider them against a tradition of practices existing in the cultural archives. Following Groys’s theory, the cultural value of ‘new’ feminist internet performance art is determined by its relationship to art historical context or lineage of similar work, in the measure of how successful the positive or negative adaptation to them is. The works of Pierce, Soda, and Man are underpinned by rich histories at the intersection of performance art, moving image, net art, and post-internet art dealing with gender, identity, and femininity.

The artistic traditions in question could be traced back to the 1970s, when Lynn Hershman Leeson started experimenting with fictional characters. Works like Roberta Breitmore (1973-1978) and Lorna (1979-1983) employed interaction and technology, such as TV and new video formats like LaserDisc, to critique the performance of gender (Harbison 70). Later, Hershman started making Internet-based projects, such as CyberRoberta (1996) (Harbison 71) to further examine the authenticity of self and the complications and anxiety emerging with the arrival of the Internet. Hershman’s The Electronic Diaries (1984-96) is a video series representative of a period in the 1980s and 1990s when artists were experimenting with cyberspace as a social space for self-representation and liberation (Harbison 7). In the videos, the artist confronts fears and traumas through recoded confessions, speaking directly to the camera. The tapes are fractured and use digital effects to reflect the psychological changes and misperceptions of self the protagonist experiences (Tromble 70). The series became a key work for the artist and for artists’ video more broadly as it restated and resonated with a lot of the feminist video themes of the preceding decade. At the same time, her work engaged with the new politics of representation that had emerged with the affordances of new communication and media technologies (Harbison 66).

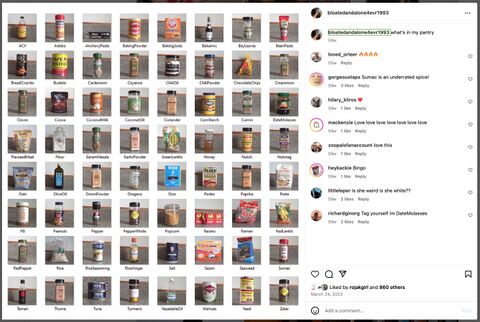

Hershman’s contribution to what Rosalind Krauss at the time had termed ‘aesthetics of narcissism’ (Krauss) was suggesting that the separation of the subject and its fictional manifestations in the electronic mirror, need to be considered not just in the immediacy of the technological medium, but in the entire system and network of televisual environment (Tromble 145). Exploring early ideas around surveillance and confronting your image in real-time through new media, Hershman stresses the need for the mediated reflection to be understood not simply as a reflection of reality but as a force which actively manipulates and constructs reality. Thus, her work presents the screen as a space where identities are negotiated, constructed, and reconstructed. Through embedding the subject’s image within a larger television context, Hershman highlights the complexities of identity as mediated, fragmented, and entangled with fictional representations in the context of the pervasive influence of television.