Pdf:APRJA Content Form: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<div id="cover-title"> | <div id="cover-title"> | ||

A Peer-Reviewed Journal About<br><br> | A Peer-Reviewed Journal About<br><br> | ||

CONTENT FORM | CONTENT/FORM | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="authors"> | <div class="authors"> | ||

& | Manetta Berends & Simon Browne<br> | ||

Kendal Beynon<br> | |||

Edoardo Biscossi<br> | Edoardo Biscossi<br> | ||

Luca Cacini<br> | |||

Esther Rizo Casado<br> | Esther Rizo Casado<br> | ||

Pierre Depaz<br> | |||

Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias<br> | Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias<br> | ||

Mateus Domingos<br> | Mateus Domingos<br> | ||

Bilyana Palankasova<br> | |||

Asker Bryld Staunæs & Maja Bak Herrie<br> | |||

Denise Helene Sumi<br> | |||

<p> | |||

Christian Ulrik Andersen <br> | |||

& Geoff Cox (Eds.)<br> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 40: | Line 43: | ||

Contents | Contents | ||

* '''Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox'''<br>[[#Editorial|Editorial: Content Form]] | * '''Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox'''<br>[[#Editorial|Editorial: Doing Content/Form]] | ||

* ''' | * '''Manetta Berends & Simon Browne'''<br>[[#wiki-to-print|About wiki-to-print]] | ||

* '''Denise Helene Sumi'''<br>[[#On_Critical_"Technopolitical_Pedagogies"|On Critical "Technopolitical Pedagogies": Learning and Knowledge Sharing with Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care]] | * '''Denise Helene Sumi'''<br>[[#On_Critical_"Technopolitical_Pedagogies"|On Critical "Technopolitical Pedagogies": Learning and Knowledge Sharing with Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care]] | ||

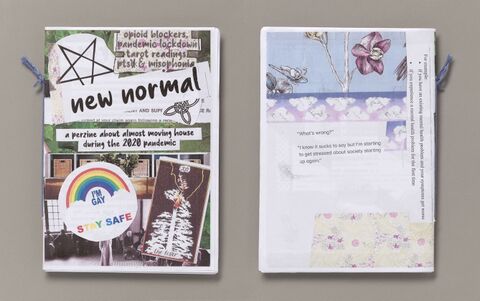

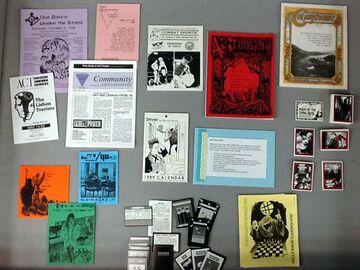

* '''Kendal Beynon'''<br>[[#Zines_and_Computational_Publishing_Practices|Zines and Computational Publishing Practices: A Countercultural Primer]] | * '''Kendal Beynon'''<br>[[#Zines_and_Computational_Publishing_Practices|Zines and Computational Publishing Practices: A Countercultural Primer]] | ||

* '''Luca Cacini'''<br>[[#The_Autophagic_Mode_of_Production|The Autophagic Mode of Production: Hacking the | * '''Bilyana Palankasova'''<br>[[#Between_the_Archive_and_the_Feed|Between the Archive and the Feed: Feminist Digital Art Practices and the Emergence of Content Value]] | ||

* '''Edoardo Biscossi'''<br>[[#Platform_Pragmatics|Platform Pragmatics: Labour, Speculation and Self-reflexivity in Content Economies]] | |||

* '''Luca Cacini'''<br>[[#The_Autophagic_Mode_of_Production|The Autophagic Mode of Production: Hacking the Metabolism of AI]] | |||

* '''Pierre Depaz'''<br>[[#Shaping_Vectors|Shaping Vectors: Discipline and Control in Word Embeddings]] | |||

* '''Asker Bryld Staunæs & Maja Bak Herrie'''<br>[[#Deep_Faking_in_a_Flat_Reality?|Deep Faking in a Flat Reality?]] | |||

* '''Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias'''<br>[[#Logics_of_War|Logics of War]] | * '''Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias'''<br>[[#Logics_of_War|Logics of War]] | ||

* ''' | * '''Esther Rizo Casado'''<br>[[#Xeno-Tuning|Xeno-Tuning: Dissolving Hegemonic Identities in Algorithmic Multiplicity]] | ||

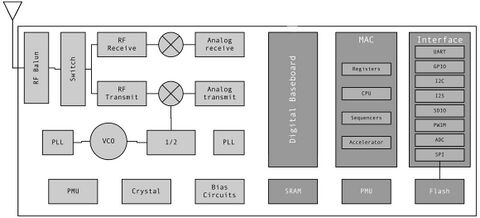

* ''' | * '''Mateus Domingos'''<br>[[#Unstable_Frequencies|Unstable Frequencies: A Case for Small-scale Wifi Experimentation]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 67: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class=" | <div class="item" id="wiki-to-print"> | ||

{{ :APRJA Content Form - Wiki-to-print }} | |||

</div> | |||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Denise Sumi }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 74: | Line 81: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Kendal Beynon }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 87: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Bilyana Palankasova }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 92: | Line 99: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Luca Cacini }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 98: | Line 105: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Pierre Depaz }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 104: | Line 111: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Asker Asker Bryld Maja Herrie }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 116: | Line 123: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Esther Rizo Casado }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 122: | Line 129: | ||

<div class="item"> | <div class="item"> | ||

{{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 | {{ :Content Form:APRJA 13 Mateus Domingos }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[Category:Content Form]] | [[Category:Content Form]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:11, 11 November 2024

Contents

- Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox

Editorial: Doing Content/Form - Manetta Berends & Simon Browne

About wiki-to-print - Denise Helene Sumi

On Critical "Technopolitical Pedagogies": Learning and Knowledge Sharing with Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care - Kendal Beynon

Zines and Computational Publishing Practices: A Countercultural Primer - Bilyana Palankasova

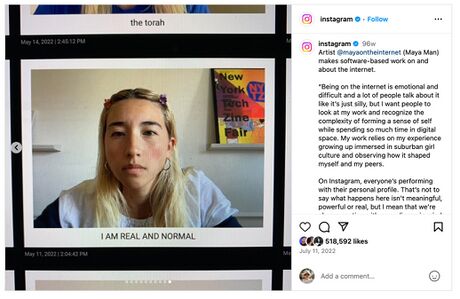

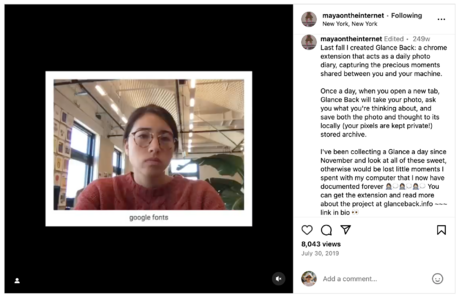

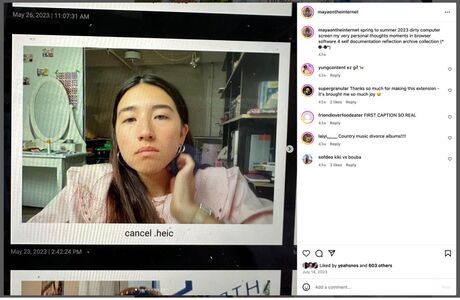

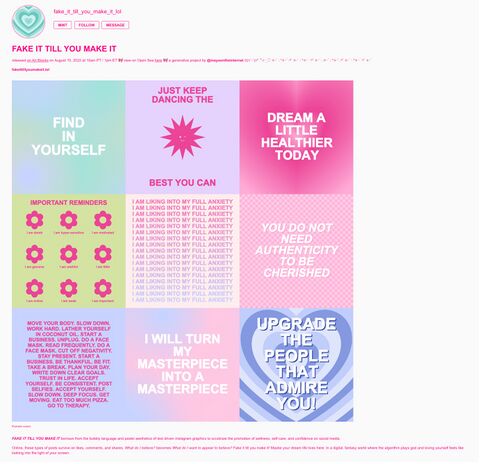

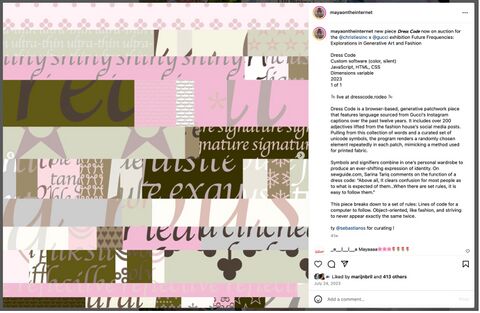

Between the Archive and the Feed: Feminist Digital Art Practices and the Emergence of Content Value - Edoardo Biscossi

Platform Pragmatics: Labour, Speculation and Self-reflexivity in Content Economies - Luca Cacini

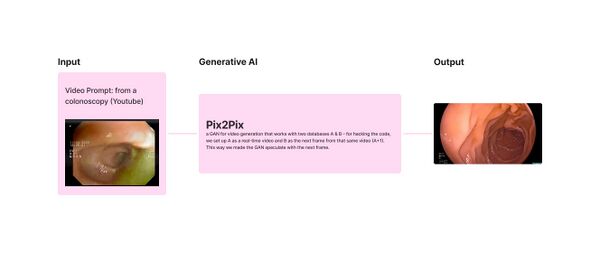

The Autophagic Mode of Production: Hacking the Metabolism of AI - Pierre Depaz

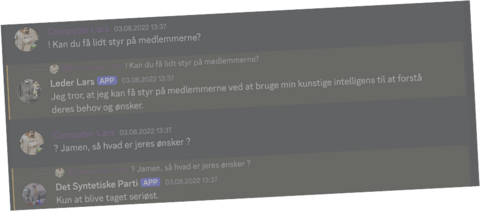

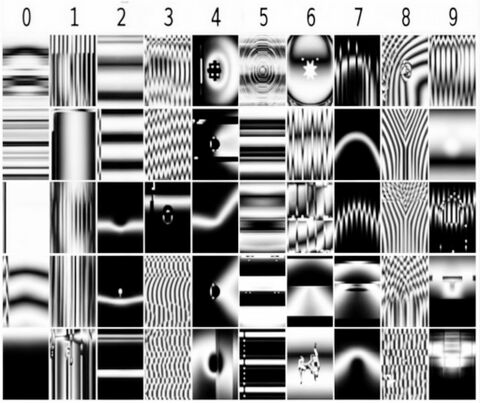

Shaping Vectors: Discipline and Control in Word Embeddings - Asker Bryld Staunæs & Maja Bak Herrie

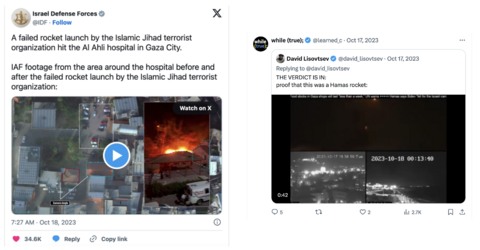

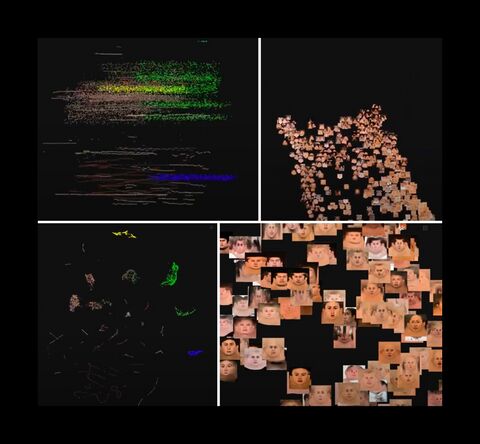

Deep Faking in a Flat Reality? - Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias

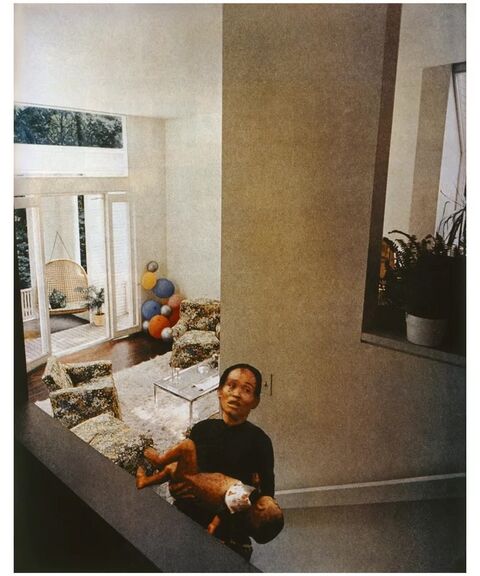

Logics of War - Esther Rizo Casado

Xeno-Tuning: Dissolving Hegemonic Identities in Algorithmic Multiplicity - Mateus Domingos

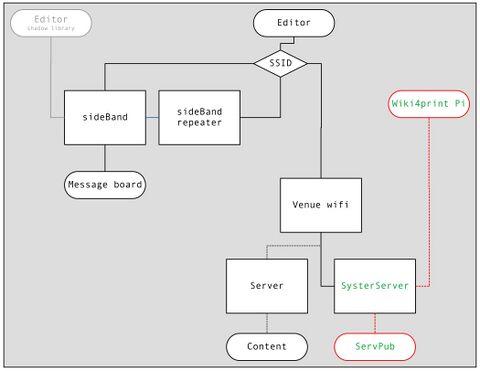

Unstable Frequencies: A Case for Small-scale Wifi Experimentation

A Peer-Reviewed Journal About_

ISSN: 2245-7755

Editors: Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox

Published by: Digital Aesthetics Research Centre, Aarhus University

Design: Manetta Berends & Simon Browne (CC)

Fonts: Happy Times at the IKOB by Lucas Le Bihan, AllCon by Simon Browne

CC license: ‘Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike’

Christian Ulrik Andersen

& Geoff Cox

Editorial

Doing Content/Form

Content cannot be separated from the forms through which it is rendered. If our attachment to standardised forms and formats – served to us by big tech – limit the space for political possibility and collective action, then we ask what alternatives might be envisioned, including for research itself?[1] What does research do in the world, and how best to facilitate meaningful intervention with attention to content and form? Perhaps what is missing is a stronger account of the structures that render our research experiences, that serve to produce new imaginaries, new spatial and temporal forms?

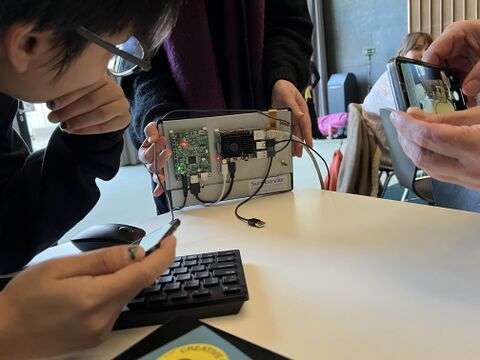

Addressing these concerns, published articles are the outcome of a research workshop that preceded the 2024 edition of the transmediale festival, in Berlin.[2] Participants developed their own research questions and provided peer feedback to each other, and prepared articles for a newspaper publication distributed as part of the festival.[3] In addition to established conventions of research development, they also engaged with the social and technical conditions of potential new and sustainable research practices – the ways it is shared and reviewed, and the infrastructures through which it is enabled. The distributed and collaborative nature of this process is reflected in the combinations of people involved – not just participants but also facilitators, somewhat blurring the lines between the two. Significantly, the approach also builds on the work of others involved in the development of the tools and infrastructures, and the short entry by Manetta Berends and Simon Browne acknowledges previous iterations of 'wiki-to-print' and 'wiki2print', which has in turn been adapted as 'wiki4print'.[4]

Approaching the wiki as an environment for the production of collective thought encourages a type of writing that comes from the need to share and exchange ideas. An important principle here is to stress how technological and social forms come together and encourage reflection on organisational processes and social relations. As Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have put it in “Publishing to Find Comrades”: “The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus.”

Using MediaWiki software and web-to-print layout techniques, the experimental publication tool/platform wiki4print has been developed as part of a larger infrastructure for research and publishing called ‘ServPub’,[5] a feminist server and associated tools developed and facilitated collectively by grassroot tech collectives In-grid[6] and Systerserver.[7] It is a modest attempt to circumvent academic workflows and conflate traditional roles of writers, editors, designers, developers alongside the affordances of the technologies in use, allowing participants to think and work together in public. As such, our claim is that such an approach transgresses conventional boundaries of research institutions, like a university or an art school, and underscores how the infrastructures of research, too, are dependent on maintenance, care, trust, understanding, and co-learning.

These principles are apparent in the contribution of Denise Sumi who explores the pedagogical and political dimensions of two 'pirate' projects: an online shadow library that serves as an alternative to the ongoing commodification of academic research, and another that offers learning resources that address the crisis of care and its criminalisation under neoliberal policies. The phrase "technopolitical pedagogies" is used to advocate for the sharing of knowledge, and to use tools to provide access to information and restrictive intellectual property laws. Further examples of resistance to dominant media infrastructures are provided by Kendal Beynon, who charts the historical parallel between zine culture and DIY computational publishing practices, including the creation of personal homepages and feminist servers, as spaces for identity formation and community building. Similarly drawing a parallel, Bilyana Palankasova combines online practices of self-documentation and feminist art histories of media and performance to expand on the notion of "content value" through a process of innovation and intra-cultural exchange.

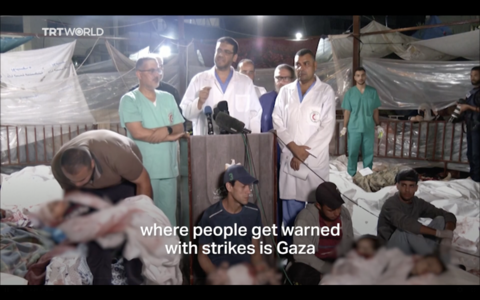

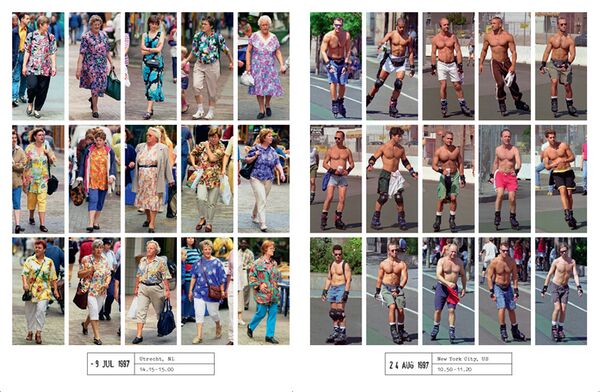

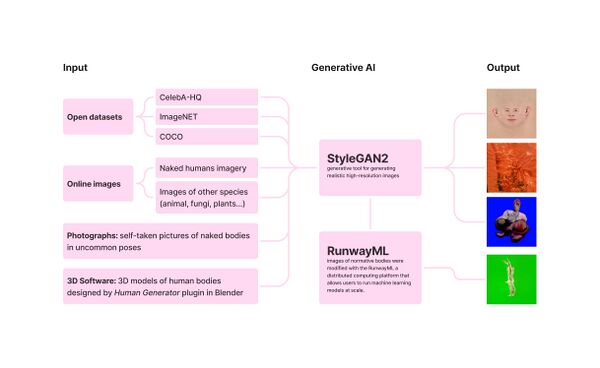

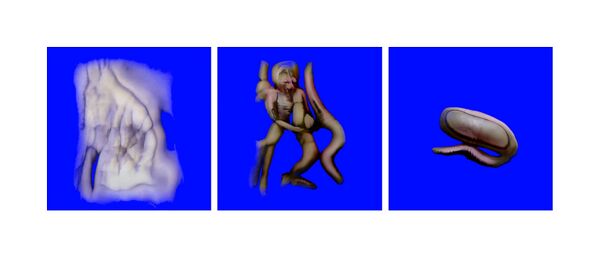

New forms of content creation are also examined by Edoardo Biscossi, who proposes "platform pragmatics" as a framework for understanding collective behaviour and forms of labour within media ecosystems. These examples of content production are further developed by others in the context of AI and large language models (LLMs). Luca Cacini characterises generative AI as an "autophagic organism", akin to the biological processes of self-consumption and self-optimization. Concepts such as “model collapse” and "shadow prompting" demonstrate the potential to reterritorialize social relations in the process of content creation and consumption. Also concerning LLMs, Pierre Depaz meticulously uncovers how word embeddings shape acceptable meanings in ways that resemble Foucault’s disciplinary apparatus and Deleuze’s notion of control societies, as such restricting the lexical possibilities of human-machine dialogic interaction. This delimitation can be also seen in the ways that electoral politics is now shaped, under the conditions of what Asker Bryld Staunæs and Maja Bak Herrie refer to as a "flat reality". They suggest "deep faking" leads to a new political morphology, where formal democracy is altered by synthetic simulation. Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias argues something similar can be seen in the mediatization of war, such as in the case of a YouTube video of a press conference held in Gaza, where evidence of atrocity co-exists with its simulated form. On the other hand, rather than seek to reject these all-consuming logics of truth or lies, Esther Rizo Casado points to artistic practices that accelerate the hallucinatory capacities of image-generating AI to question the inherent power dynamics of representation, in this case concerning gender classifications. Using a technique called "xeno-tuning", pre-trained models produce weird representations of corporealities and hegemonic identities, thus making them transformative and agential. Falsifications of representation become potentially corrective of historical misrepresentation.

Returning to the workshop format, Mateus Domingos describes an experimental wi-fi network related to the feminist methodologies of ServPub. This last contribution exemplifies the approach of both the workshop and publication, drawing attention to how constituent parts are assembled and maintained through collective effort. This would not have been possible without the active participation of not only those mentioned to this point, the authors of articles but also the grassroots collectives who supported the infrastructure, and the wider network of participant-facilitators (which includes Rebecca Aston, Emilie Sin Yi Choi, Rachel Falconer, Mara Karagianni, Mariana Marangoni, Martyna Marciniak, Nora O' Murchú, ooooo, Duncan Paterson, Søren Pold, Anya Shchetvina, George Simms, Winnie Soon, Katie Tindle, and Pablo Velasco). In addition, we appreciate the institutional support of SHAPE Digital Citizenship and Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University, the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University, the Creative Computing Institute at University of the Arts, London, and transmediale festival for art and digital culture, Berlin. This extensive list of credits of human and nonhuman entities further underscores how form/content come together, allowing one to shape the other, and ultimately the content/form of this publication.

Notes

- ↑ With this in mind, the previous issue of APRJA used the term "minor tech", see https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

- ↑ Details of tranmediale 2024 can be found at https://transmediale.de/en/2024/sweetie. Articles are derived from short newspaper articles written during the workshop.

- ↑ The newspaper can be downloaded at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/File:Content-Form_A-Peer-Reviewed-Newspaper-Volume-13-Issue-1-2024.pdf

- ↑ See the article that follows for more details on this history, also available at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Wiki-to-print.

- ↑ For more information on ServPub, see https://servpub.net/.

- ↑ In-grid, https://www.in-grid.io/

- ↑ Systerverver, https://systerserver.net/

Works cited

Andersen, Christian, and Geoff Cox, eds., A Peer Reviewed Journal About Minor Tech, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2023), https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

Shukaitis, Stevphen, and Joanna Figiel, "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of Temporality and Solidarity in Autonomous Print Cultures," Lateral Vol. 8, No. 2 (2019), https://csalateral.org/issue/8-2/publishing-comrades-temporality-solidarity-autonomous-print-cultures-shukaitis-figiel

Biographies

Christian Ulrik Andersen is Associate Professor of Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University, and currently a Research Fellow at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies.

Geoff Cox is Professor of Art and Computational Culture at London South Bank University, Director of Digital & Data Research Centre, and co-Director of Centre for the Study of the Networked Image.

Manetta Berends & Simon Browne

About wiki-to-print

This journal is made with wiki-to-print, a collective publishing environment based on MediaWiki software[1], Paged Media CSS[2] techniques and the JavaScript library Paged.js[3], which renders a preview of the PDF in the browser. Using wiki-to-print allows us to work shoulder-to-shoulder as collaborative writers, editors, designers, developers, in a non-linear publishing workflow where design and content unfolds at the same time, allowing the one to shape the other.

Following the idea of "boilerplate code" which is written to be reused, we like to think of wiki-to-print as a boilerplate as well, instead of thinking of it as a product, platform or tool. The code that is running in the background is a version of previous wiki-printing instances, including:

- the work on the Diversions[4] publications by Constant[5] and OSP[6]

- the book Volumetric Regimes[7] by Possible Bodies[8] and Manetta Berends[9]

- TITiPI's[10] wiki-to-pdf environments[11] by Martino Morandi

- Hackers and Designers'[12] version wiki2print[13] that was produced for the book Making Matters[14]

So, wiki-to-print/wiki-to-pdf/wiki2print is not standalone, but part of a continuum of projects that see software as something to learn from, adapt, transform and change. The code that is used for making this journal is released as yet another version of this network of connected practices[15].

This wiki-to-print is hosted at CC[16] (creative crowds). While moving from cloud to crowds, CC is a thinking device for us how to hand over ways of working and share a space for publishing experiments with others.

Notes

- ↑ https://www.mediawiki.org

- ↑ https://www.w3.org/TR/css-page-3/

- ↑ https://pagedjs.org

- ↑ https://diversions.constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://osp.kitchen

- ↑ http://data-browser.net/db08.html + https://volumetricregimes.xyz

- ↑ https://possiblebodies.constantvzw.org

- ↑ https://manettaberends.nl

- ↑ http://titipi.org

- ↑ https://titipi.org/wiki/index.php/Wiki-to-pdf

- ↑ https://hackersanddesigners.nl

- ↑ https://github.com/hackersanddesigners/wiki2print

- ↑ https://hackersanddesigners.nl/s/Publishing/p/Making_Matters._A_Vocabulary_of_Collective_Arts

- ↑ https://git.vvvvvvaria.org/CC/wiki-to-print

- ↑ https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org

Denise Helene Sumi

On Critical "Technopolitical Pedagogies"

On Critical "Technopolitical Pedagogies"

Learning and Knowledge Sharing with Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care

Abstract

This article explores the pedagogical and political dimensions of the projects Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care. Public Library/Memory of the World (2012–ongoing) by Marcell Mars and Tomislav Medak serves as an online shadow library in response to the ongoing commodification of academic research and threats to public libraries. syllabus⦚ Pirate Care (2019), a project initiated by Valeria Graziano, Mars, and Medak, offers learning resources that address the crisis of care and its criminalisation under neoliberal policies. The article argues that by employing "technopolitical pedagogies" and advocating the sharing of knowledge, these projects enable forms of practical orientation in a complex world of political friction. They use network technologies and open-source tools to provide access to information and support civil disobedience against restrictive intellectual property laws. Unlike other scalable "pirate" infrastructures, these projects embrace a nonscalable model that prioritises relational, context-specific engagements and provides tools for the creation of similar infrastructures. Both projects represent critical pedagogical interventions, hacking the monodimensional tendencies of educational systems and library catalogues, and produce commoner positions.

What Is the Purpose of Pedagogy? Or How to Compose Content

Every human lives in a world. Worlds are composed of contents, the identification of those contents, and by the configuration of content relations within — semantically, operationally and axiologically. [...] The identification of the contents of a world and its relational configuration is what establishes frames of reference for practical orientation. (Reed 1)

This quote, taken from the opening words of Patricia Reed's essay "The End of a World and Its Pedagogies" offers a good entry point for what will be discussed below in relation to the two projects Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care. Public Library/Memory of the World is an online shadow library initiated in 2012 by Marcell Mars and Tomislav Medak in a situation where knowledge and academic research was, and still is, largely commodified and followed the logics of property law, when public libraries were threatened by austerity measures and existing shadow libraries were increasingly threatened by lawsuits (Mars and Medak 48). As a continuation of Memory of the World, and as a response to a period of neoliberal politics in which care is "increasingly defunded, discouraged and criminalised," syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care was initiated in 2019 by Valeria Graziano, Mars and Medak (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 2). It is an online syllabus that provides information on initiatives that counter the criminalisation of care in a neoliberal system. The following text will discuss the two projects and argue that they produce and distribute content that can be linked back to their specific form of "technopolitical pedagogy" and commoning of knowledge, thus producing a specific practical and political orientation in the world (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 7). Practical orientation, with reference to Reed, is understood as a method of situating oneself within a complex and shifting reality and paying particular attention to the vectors and structures of specific relations and their activations. Practical orientation requires an active position in the development of new frameworks. If we understand content and information retrieval as a political project in itself (Kolb and Weinmayr 1), then what content we are able to access and how we are able to access is matters in relation to how worlds are composed.

These two projects were specifically chosen because they differ from similar "pirate" infrastructures such as sci-hub or library genesis in that they operate differently and are relatively small in scale. In her text "On Nonscalability", Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing argues for the development of a "theory of nonscalability", which she defines as the negative of scalability (Lowenhaupt Tsing 507). "Scalable projects"," she writes, "are those that can expand without changing" (Lowenhaupt Tsing 507). While she refers to relationships as "potential vectors of transformation" (Lowenhaupt Tsing 507), the content of both Public Library/Memory of the World and Syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care is presented with a strong reference to the librarians, authors, activists, and initiatives assembled, thus potentially allowing for a relationship with the non-interchangeable people behind the projects or book collections. Both projects provide not only the content, but also the tools to recreate such infrastructures/forms in different contexts and are therefore non static. The two projects differ from similar pirate structures in that they are not scalable in their current form and provide toolkits for recreating similar infrastructures. They are not a project of "uniform expansion", but capable of forming relations of care rather than modes of alienation (Lowenhaupt Tsing 507).

In the essay quoted above, Reed discusses the concept of worlds (actual worlds or models) as frameworks of inhabitation, shaped by content-related relations that create practical orientations. She argues that the current globalised world is characterised by monodimensional tendencies, leading to a "making-small of worlds" and a reduction of content and diversity (a similar argument to that of Lowenhaupt Tsing regarding the modern project of scalability in the sense of growth and expansion). This tendency to make "small worlds" is a familiar metaphor for describing the topologies of network technologies (Watts). One guiding question of this essay is how projects such as Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care can counteract this making-small of worlds. Reed explores how worlds endure through their ability to absorb friction but come to an end when they fail to do so. She points to a disparity created by what she calls the "insuppressible friction" of "Euromodern" and "globalising practices" with "the planetary" and suggests that at the end of a world, when frictions are no longer absorbed, pedagogies must attune by adapting to existing configurations and imagining other worlds (Reed 3). Although Reed focuses on the "insuppressible friction" around the disparity of the Euromodern and the planetary, I intend to apply her argument that pedagogies must attune to learn to absorb the disparity created by frictions otherwise — namely to a state where the disparity for a political desire for a monodimensional world order, a pluriversal world order, or one that understands the world as complex "dynamic cultural fabric" becomes irrepressible (Rivera Cusicanqui 107). What is the purpose of any pedagogy if not to absorb these very political frictions?

Then, what is the purpose of pedagogy, of a school, of a university? Gary Hall, critical theorist and media philosopher, answers this question as follows:

One of the purposes of a university is to create a space where society's common sense ideas can be examined and interrogated, and to act as a testing ground for the development of new knowledges, new subjectivities, new practices and new social relations of the kind we are going to need in the future, but which are often hard — although not impossible — to explore elsewhere. (Hall 169)

This essay is written at a time when pro-Palestinian protests on US campuses are spreading to European and Middle Eastern universities. According to the Crowd Counting Consortium, more than 150 pro-Palestinian demonstrations took place on US campuses between April 17 and 30, 2024. The same Washington Post article that reported these figures affirmed that state, local, and campus police, often in riot gear, monitored or dispersed crowds on more than eighty campuses (Rosenzweig-Ziff et al.). While their presence was often requested by university administrations themselves, by the early morning of May 17, 2024, more than 2,900 people had been arrested at campus protests in the US (Halina et al.). It is in this climate at universities, Hall’s statement quoted above about the university as a space for testing new social relations and new subjectivities needs to be critically reconsidered, as well as the university, its libraries, and archives as citadels of knowledge. Another level on which this text argues in favor of learning from and with projects such as Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care and its everyday and critical pedagogies , is the growing discussion about the decolonisation of libraries in the Global North; about how knowledge has been catalogued, collected, and stored in these library catalogues; about what socially and historically generated orders and hierarchies underlie them, and what content has been left out by which authors (Kolb and Weinmayr 1).

If knowledge — including academic research, books, and papers being produced by scholars and researchers — is to circulate in a multitude of ways, then ways of sharing this knowledge and spaces for learning should be supported, enhanced, and presented alongside an institutional setting. Learning and producing knowledge from within institutions should not exclude learning from and sharing with the periphery. Any form of knowledge can never be entirely public or private but must involve a variety of "modes of authorship, ownership and reproduction", as Hall writes (161). These distributed modes of authorship, ownership, and reproduction protect a society from knowledge being censored or even destroyed — and so worlds, histories, and biographies can continue to flourish and be discussed from different perspectives. In addition to state educational institutions such as universities, libraries, and state archives, other pillars within societies are needed to preserve and disseminate knowledge.

In the book School: A Recent History of Self-Organized Art Education, Sam Thorne has collected conversations that feature projects that enable alternative pedagogical practices or “radical education” outside of large state institutions, such as the Silent University in Boston; the School for Engaged Art in St. Petersburg/Berlin, associated with the collective and magazine Chto Delat; or the Public School founded by Sean Dockray and Fiona Whitton, associated with the platform AAAARG.org, among many others (Thorne 26). With his contribution to the field, Thorne gathers examples of "flexible, self-directed, social and free" and often "small", "non-standardized" programmes and formats for general education (Thorne 31ff). Within this trajectory of self-organised educational platforms and critical/radical pedagogies, the focus on Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus⦚ Pirate Care may offer a response to the increasingly repressive climate within public educational institutions, the critical review of existing library catalogues, and the "circuits of academic publishing" still largely controlled by these same institutions alongside a profitable academic publishing industry (Mars and Medak 60). Unlike most of the examples in School, the two examples I want to discuss are defined by the fact that they are not site-specific, but make use of network technologies and infrastructures, and therefore offer a reassessment of the question of how to use the possibilities of knowledge circulation offered by technological networks, thinking alongside questions of authorship, ownership, and reproduction, as well as the maintenance and care of knowledge.

Both projects will be discussed as examples of "techno-cultural formulations" (Goriunova 44) that embed critical pedagogies and not only address the current regulations of the circulation of knowledge and the criminalisation of care and solidarity that coinsides with it, but also offer tools and strategies to oppose these mechanisms individually and collectively. Goriunova's notion of "techno-cultural formations" refers to the ways in which technology and cultural practices co-evolve and shape one another and how these interactions produce new forms of culture and social organization, not falling into the narrative of techno-determinism. While “techno-cultural formations” play a crucial role in how knowledge is being navigated or retrieved, this essay argues, that it is all the more important to pay attention to critical pedagogies within techno-cultural formations as well as the content-form relation of certain formations. In order to better understand how techno-cultural formations shape social organisation differently from techno-determinism, the next part will make a small excursion to describe how distributed network technologies have been used in the last two decades to further confuse practical orientation, before returning to the actual projects.

From the Citadel to Calibre: Becoming an Autonomous Amateur Librarian

The push to disorient and capitalise on the "hyper-emotionalism of post-truth politics" (Hall 172), together with the rise of the digital platform economy, where companies such as Google or Amazon connect users and producers and extract value from the data generated by their interactions, transforming labour and further concentrating capital and power (Srnicek), has become increasingly influential in the politics of the last two decades. These developments have further confused the practical orientation and identification of information and content, and created political frictions. What became known as the Cambridge Analytica data scandal revealed to a wider public that the populist authoritarian right was exploiting the possibilities of network and communication technologies for its own ends. What Alexander Galloway observed in his 2010 essay "Networks" became clear:

Distributed networks have become hegemonic only recently, and because of this it is relatively easy to lapse back into the thinking of a time when networks were disruptive of power centers, when the guerilla threatened the army, when the nomadic horde threatened the citadel. But this is no longer the case. The distributed network is the new citadel, the new army, the new power. (Galloway 290)

In the same essay, Galloway points out the inherent contradictions within networked systems — how they simultaneously enable open access and impose new forms of regulation, thus he called for a "critical theory" when applying the network form (Galloway 290). Although, in 2010, Galloway was still very much focusing on distributed networks as the new citadel, when in fact it was the scale-free networks that a few years later made it possible for the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica data scandal to fully unfold at the scale it did. In her award-winning article, investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr reveals the mechanisms and scale by which data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica harvested data from individual Facebook users to supply to political campaigns, including Donald Trump's 2015 presidential campaign and the Brexit campaign. Cadwalladr compares the massive scandal to a "massive land grab for power by billionaires via our data". She wrote: "Whoever owns this data owns the future".

In their text "System of a Takedown" on circuits of academic publishing, Mars and Medak remind us that the modern condition of land grabbing and that of intellectual property, and thus copyright for digital and discrete data, have the same historical roots in European absolutism and early capitalism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Intellectual labour in the age of mechanical reproduction, they say, has been given an unfortunate metaphor: "A metaphor modeled on the scarce and exclusive character of property over land." (Mars and Medak 49) Mars and Medak refer to a complex interplay between capital flows, property rights, and the circuits of academic publishing. In their text, they essentially criticise what they call the “oligopoly” of academic publishing. Mars and Medak state that in 2019, academic publishing was a $10 billion industry, 75 percent of which was funded by university library subscriptions. They go on to show that the major commercial publishers in the field make huge profit margins, regularly over 30 percent in the case of Reed Elsevier, and not much less in the case of Taylor and Francis, Springer, Wiley-Blackwell, and others. Mars and Medak argue that publishers maintain control over academic output through copyright and reputation mechanisms, preventing alternatives such as open access from emerging. They suggest that this control perpetuates inequality and limits access to knowledge (Mars and Medak 49). Mars and Medak follow a trajectory in their critique of the regulation of the circulation of knowledge. In his 2008 "Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto", programmer and activist Aaron Swartz criticised the academic publishing system and advocated civil disobedience to oppose these mechanisms:

The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations. [...] It's outrageous and unacceptable. [...] We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world. We need to take stuff that's out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks.” (Swartz 2008)

A few years prior to the publication of the "Guerilla Open Access Manifesto", the "Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities" was presented. The declaration points out that the internet offers an opportunity to create a global and interactive repository of scientific knowledge and cultural heritage, which could be distributed through the means of networking. The declaration calls on policymakers, research institutions, funding agencies, libraries, archives, and museums to consider its call to action and to implement open-access policies. More than twenty years later, access to this particular system that legally circulates academic knowledge remains accessible only to a few privileged students, professors, and university staff. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights' call for equal access to education is in no way supported by a system in which knowledge is still treated as a scarcity rather than a common good. Under these continuing conditions, Mars and Medak argue that courts, constrained by viewing intellectual property through a copyright lens, have failed to reconcile the conflict between access to knowledge and fair compensation for intellectual labour. Instead, they have overwhelmingly supported the commercial interests of major copyright industries, further deepening social tensions through the commodification of knowledge in the age of digital reproduction (Mars and Medak 2019). For this reason, Mars and Medak suggest that copyright infringement (in relation to academic publishing circuits) is not a matter of illegality, but of "legitimate action" (Mars and Medak 55). They argue that a critical mass of infringement is necessary for such acts to be seen as legitimate expressions of civil disobedience. The author of Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates, Adrian Johns, writes that

"information has become a key commodity in the globalized economy and that piracy today goes beyond the theft of intellectual property to affect core aspects of modern culture, science, technology, authorship, policing, politics, and the very foundations of economic and social order. [...] That is why the topic of piracy causes the anxiety that it so evidently does. [...] The pirates, in all too many cases, are not alienated proles. Nor do they represent some comfortingly distinct outside. They are us. (Johns 26)

On his personal blog, Mars explains how to become an autonomous online librarian by sharing books using network technologies to contribute to critical mass. Calibre, an open-source software, allows you to create an individual database for a book/PDF collection (Mars). Calibre semiautomatically collects metadata from online sources. Each individual collection can be shared in a few simple steps when connected to a LAN (local area network). The entire collection can also be made available to others over the internet (outside the LAN). This is a bit more complex, but easy to learn and use. These mechanisms — a database and some basic knowledge of how to use networking technologies — form the basis of contributing to systems like the Public Library/Memory of the World. Database software like Calibre, networking technologies and tutorials like Mars's, as well as the maintenance of the website itself, make it possible to become an autonomous amateur librarian: knowledge can be made freely available by the many for the many. A project like Public Library/Memory of the World creates a potential for decentralisation, bringing together materials and perspectives that are not already validated or authorised by the formalised environment of an institutional library (Kolb and Weinmayr 2), but allowing for "flexible, self-directed, social and free" and many "small", "non-standardised", and independent libraries and learning platforms, like those presented by Thorne (31). As of May 23, 2024, the library currently offers access to 158,819 books, available in PDF or EPUB format, maintained and offered by twenty-six autonomous librarians, that you could potentially contact in one way or another.

Learning with Syllabi: Becoming a "Subject Position"

While Public Library/Memory of the World is often referenced in discussions of the commons, open access, online piracy, and shadow libraries (Sollfrank, Stalder, and Niederberger), syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care can be situated in the political tradition of radical writing and publishing in a new media environment (Dean et al.). Alongside this tradition, the initiators Graziano, Mars, and Medak claim that the project is in fact a continuation of the shadow library and its particular ethics and is using pedagogy as an "entry point" (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 4). Inspired by "online syllabi generated within social justice movements" such as #FergusonSyllabus (2014), #BlkWomenSyllabus (2015), #SayHerNameSyllabus (2015), #StandingRockSyllabus (2016), or #BLMSyllabus (2015/2016) (Learning with Syllabus), syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care serves as a transnational research project involving activists, researchers, hackers, and artists concerned with the "crisis of care" and the criminalisation of solidarity in "neoliberal politics" (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 117). After an introduction to the syllabus and its content, summaries, reading lists, and resources from the introductory sessions "Situating Care", "The Crisis of Care and its Criminalisation", "Piracy and Civil Disobedience, Then and Now", as well as guidance for exercises, are provided. Each session/section is accompanied by an exhaustive list of references and resources, as well as links to access the resources. This is followed by more detailed insights into civic and artistic projects and activist practices such as "Sea Rescue as Care", "Housing Struggles", "Transhackfeminism", and "Hormones, Toxicity and Body Sovereignty", to name but a few. Regarding its specific pedagogies and "technopolitics", it explains that:

We want the syllabus to be ready for easy preservation and come integrated with a well-maintained and catalogued collection of learning materials. To achieve this, our syllabus is built from plaintext documents that are written in a very simple and human-readable Markdown markup language, rendered into a static HTML website that doesn’t require a resource-intensive and easily breakable database system, and which keeps its files on a git version control system that allows collaborative writing and easy forking to create new versions. Such a syllabus can be then equally hosted on an internet server and used/shared offline from a USB stick. (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 5)

In addition to the static website (built with Hugo), it is possible to generate a PDF of the entire syllabus with a single click (this feature is built into the website using Paged.js). Some of the topics are linked to a specific literature repository on the shadow library Public Library/Memory of the World. The curriculum lives on a publishing platform, Sandpoints, developed by Mars. Sandpoints enables collaborative writing, remixing, and maintenance of a catalogue of learning resources as "concrete proposals for learning" (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 4). The source code for the software is made available via GitHub, and all "original writing" within the syllabus is released "under CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0), Public Domain Dedication, No Copyright" and users are invited to use the material in any way (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 6). The arrangement of this specific form of "Pirate Care" — an open curriculum linked to a shadow library, built with free software, together with the call for collective action — produces and distributes activities and content that can be linked back to the specific form of solidarity and ethics that the project is concerned with.

The specific technopolitical pedagogies of the two projects discussed do indeed apply a critical theory when using the network form, thus allowing for a practical orientation (especially when engaging with techno-cultural formulations.) They do so by exploring the specific content-form relations of research practices and their tools themselves; by advocating for the implementation of care in the network form; and by applying methodologies for commoning for enabling transversal knowledge exchange. They do so while embracing the opportunities offered by network technologies, calling for "technologically-enabled care and solidarity networks" (syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care 2). These systems are in place to support the use of experimental web publishing tools. By distributing information outside dominant avenues, Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus⦚ Pirate Care continue to challenge the "unusable politics" (transmediale) and "unjust laws" (Swartz) that continue to produce harmful environments, offering a reassessment of the inherently violent dynamics of the realities of Publishing (with a capital P) (Dean et al.), the circulation of information as a commodity, and imperialist logics of structural discrimination. As a model for commoning knowledge in the form of a technically informed care infrastructure, the project not only enables its users to engage with the syllabus and library as a curriculum, but also to build and maintain similar infrastructures. As an alternative publishing infrastructure, these projects continue to have an impact on politics, pedagogies, and governance and can serve as models to carefully institute. In their 2022 publication "Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care", the Institute for Technology in the Public Interest (TITiPI) explore how big tech continues to intervene in the public realm. Therefore, TITiPI asks: "How can we attend to these shifts collectively in order to demand public data infrastructures that can serve the greater public good?" (TITiPI 2022)

Projects such as Public Library/Memory of the World and syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care produce what Goriunova — with reference to the conceptual persona in Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s “What is Philosophy?” — has called a "subject position", one that is "abstracted from the work and structures of shadow libraries, repositories and platforms" and that operates in the world in relation to subjectivities (Deleuze and Guattari; Goriunova 43). Goriunova's subject position is one that is radically different from what Hall recalls when he speaks of new subjectivities being formed within universities. In relation to making and using and learning with a shadow library like Public Library/Memory of the World or a repository like syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care, Goriunova states:

They [the subject positions] are formed as points of view, conceptual positions that create a version of the world with its own system of values, maps of orientation and horizon of possibility. A conceptual congregation of actions, values, ideas, propositions creates a subject position that renders the project possible. Therefore, on the one hand, techno-cultural gestures, actions, structures create subject positions, and on the other, the projects themselves as cuts of the world are created from a point of view, from a subject position. This is neither techno-determinism, when technology defines subjects, nor an argument for an independence of the human, but for a mutual constitution of subjects and technology through techno-cultural formulations. (Goriunova 43)

When one actively engages with network technologies, shadow libraries, repositories, and independent learning platforms, a subject position is constantly abstracted and made manifest. I would add to that, when one actively engages with network technologies, shadow libraries, repositories, and independent learning platforms a "commoner position" is constantly abstracted and made manifest. Galloway uses the Greek "Furies" as a metaphor for the "operative divinity" in the anti-hermeneutic tradition of networks and calls for a "new model of reading [...] that is not hermeneutic in nature but instead based on cybernetic parsing, scanning, rearranging, filtering, and interpolating" (Galloway 290). The Furies, which occur above all when human justice and the law fail somewhere, are suddenly reminiscent of the figure of the pirate that disobeys "unjust legal" and "social rules" (Graziano, Mars 141). The question remains: How can pedagogy attune so that it can create commoner positions that are willing to take on the work of the furies and the pirates, the work of parsing, scanning, rearranging, filtering, and interpolating? Who owns and shares the content that composes our dialogues and worlds?

Works cited

Cadwalladr, Carole. "The Great British Brexit Robbery: How Our Democracy Was Hijacked." The Guardian, May 7, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/may/07/the-great-british-brexit-robbery-hijacked-democracy. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. "Ch'ixinakax utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization." South Atlantic Quarterly (2012) 111 (1): 95–109.

Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities, 2003. https://openaccess.mpg.de/Berlin-Declaration. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Bennet, Halina, Olivia Bensimon, and Anna Betts, et al. "Where Protesters on U.S. Campuses Have Been Arrested or Detained." New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/us/pro-palestinian-college-protests-encampments.html. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Dean, Jodi, Sean Dockray, Alessandro Ludovico, Pauline van Mourik Broekman, Nicholas Thoburn, and Dimitry Vilensky. "Materialities of Independent Publishing: A Conversation with AAAAARG, Chto Delat?, I Cite, Mute, and Neural." New Formations 78 (2013): 157–78.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. What is Philosophy?, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. Columbia University Press, 1994.

Galloway, Alexander R. "Networks." In Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen, 280–96. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Goriunova, Olga. "Uploading Our Libraries: The Subjects of Art and Knowledge Commons." In Aesthetics of the Commons, edited by Cornelia Sollfrank, Felix Stalder, and Shusha Niederberger, 41–62. Diaphanes, 2021.

Graziano, Valeria, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak. "Learning from #Syllabus." In State Machines: Reflections and Actions at the Edge of Digital Citizenship, Finance, and Art, edited by Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, and Inte Gloerich, 115–28. Institute of Network Cultures, 2019.

———. "When Care Needs Piracy: The Case for Disobedience in Struggles Against Imperial Property Regimes." In Radical Sympathy, edited by Brandon LaBelle, 139–56. Errant Bodies Press, 2022.

Graziano, Valeria, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak, eds. syllabus ⦚ Pirate Care. 2019. https://syllabus.pirate.care. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Hall, Gary. "Postdigital Politics." In Aesthetics of the Commons, edited by Cornelia Sollfrank, Felix Stalder, and Shusha Niederberger, 153–80. Diaphanes, 2021.

Johns, Adrian. Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Kolb, Lucie, and Eva Weinmayr. "Teaching the Radical Catalog — A Syllabus." Arbido: Dekolonialisierung von Archiven 1 (2024). https://arbido.ch/de/ausgaben-artikel/2024/dekolonialisierung-von-archiven-decolonisation-des-archives/teaching-the-radical-catalog-a-syllabus. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Lowenhaupt Tsing, Anna. "On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales." Common Knowledge, Vol. 18, Issue 3, Fall 2012, 505-524.

Mars, Marcell. "Let’s Share Books." Blog post. January 30, 2011. https://blog.ki.ber.kom.uni.st/lets-share-books. Accessed May 22, 2024.

———. "Public Library/Memory of the World: Access to Knowledge for Every Member of Society." 32C3, CCC Congress, 2015. https://media.ccc.de/v/32c3-7279-public_library_memory_of_the_world. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Mars, Marcell, and Tomislav Medak. "System of a Takedown: Control and De-commodification in the Circuits of Academic Publishing." In Archives, edited by Andrew Lison, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak, and Rick Prelinger, 47–68. Meson Press, 2019.

Memory of the World, eds. Guerrilla Open Access — Memory of the World. Post Office Press, Rope Press, and Memory of the World, 2018.

Reed, Patricia. "The End of a World and Its Pedagogies." Making & Breaking 2 (2021). https://makingandbreaking.org/article/the-end-of-a-world-and-its-pedagogies. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Rosenzweig-Ziff, Dan, Clara Ence Morse, Susan Svrluga, Drea Cornejo, Hannah Dormido, and Júlia Ledur. "Riot Police and Over 2,000 Arrests: A Look at 2 Weeks of Campus Protests." Washington Post, May 3, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2024/university-antiwar-campus-protests-arrests-data/. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Sollfrank, Cornelia, Felix Stalder, and Shusha Niederberger, eds. Aesthetics of the Commons. Diaphanes, 2021.

Srnicek, Nick. Platform Capitalism. Polity Press, 2016.

Swartz, Aaron. "Guerilla Open Access Manifesto." July 2008. https://archive.org/details/GuerillaOpenAccessManifesto. Accessed May 22, 2024.

The Institute for Technology in the Public Interest, Helen V. Pritchard, and Femke Snelting, eds. Infrastructural Interactions: Survival, Resistance and Radical Care, 2022. http://titipi.org/pub/Infrastructural_Interactions.pdf. Last accessed May 22, 2024.

Thorne, Sam. School: A Recent History of Self-Organized Art Education. Sternberg Press, 2017.

transmediale 2024. https://transmediale.de/de/2024/sweetie. Accessed May 22, 2024.

Watts, Duncan. Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks between Order and Randomness. Princeton University Press, 2003.

Biography

Denise Helene Sumi (she/her) is a curator, editor, and researcher. She works as a doctoral researcher at the Peter Weibel Institute for Digital Cultures at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and has been the coordinator of the Digital Solitude program at the international and interdisciplinary artist residency Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, from 2019 to 2024. Her research focuses on the mediation of artistic experimental directions that establish and maintain technology-based relationships, lateral knowledge exchange, and collective approaches. Sumi was editor in chief of the Solitude Journal and is cofounder of the exhibition space Kevin Space, Vienna. Her writing and interviews have been published in springerin, Camera Austria, Spike Art Quarterly, Solitude Journal, Solitude Blog, and elsewhere.

Kendal Beynon

Zines and Computational Publishing Practices

Zines and Computational Publishing Practices

A Countercultural Primer

Abstract

This paper explores the parallels between historical zine culture and contemporary DIY computational publishing practices, highlighting their roles as countercultural movements within their own right. Both mediums, from zines of the 1990s to personal homepages and feminist servers, provide spaces for identity formation, community building, and resistance against mainstream societal norms. Drawing on Stephen Duncombe's insights into zine culture, this research examines how these practices embody democratic, communal ideals and act as a rebuttal to mass consumerism and dominant media structures. The paper argues that personal homepages and web rings serve as digital analogues to zines, fostering participatory and grassroots networks and underscores the importance of these DIY practices in redefining production, labour, and the role of the individual within cultural and societal contexts, advocating for a more inclusive and participatory digital landscape. Through an examination of both zines and their digital counterparts, this research reveals their shared ethos of authenticity, creativity, and resistance.

Introduction

In the contemporary sphere of machine-generated imagery, internet users seek a space to exist outside of the dominant society using the principles of do-it-yourself (DIY) ideology. Historically speaking, this phenomenon is hardly a novel movement, within the field of subcultural studies, we can see these acts of resistance through zine culture as early as the early 1950s. In Stephen Duncombe's seminal text, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, he describes zines as "noncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their creators produce, publish and distribute by themselves" (Duncombe 10-11). The content of these publications offers an insight into a radically democratic and communal ideal of a potential cultural and societal future. Zines are also an inherently political form of communication. Separating themselves from the mainstream, Elke Zobl states "the networks and communities that zinesters build among themselves are "undoubtedly political" and have “potential for political organization and intervention" (Zobl 6). These feminist approaches to zinemaking allow zinemakers to link their own lived experience to larger communal contexts politicising their ideals within a wider social context, allowing space for alternative narratives and futures. In the book mentioned earlier, in an updated afterword for 2017, Duncombe explicitly states: "One could plausibly argue that blogs are just ephemeral (...) zines".

Continuing this train of thought, this paper puts forward the argument that certain computational publishing practices act as a digital counterpoint and parallel to their physical peer, the zine. Within the context of this research, computational publishing practices refers to personal homepages and self-sustaining internet communities, and feminist server practices. The use of the term 'computational publishing' refers to practices of self-publishing both on a personal and collaborative level, while also taking into consideration the open-source nature of code repositories within feminist servers. Both mediums of a countercultural movement, zines and DIY computational publishing practices offer a space to explore the formation of identity, the construction of networks and communities and also aim to reexamine and reconfigure modes of production and the role of labour within these amateur practices. This paper aims to chart the similarities and connections that link the two practices and explore how they occupy the same fundamental space in opposition to dominant society.

Personalising Identity

Zines are commonly crafted by individuals from vastly diverse backgrounds, but one thing that links them all is their self-proclaimed title of 'losers'. In adopting this moniker, zinesters identify themselves in opposition to mainstream society. Disenfranchised from the prescribed representation offered in traditional media forms, zinemakers operate within the frame of alienation to establish self as an act of defiance. As Duncombe writes, zines are a "haven for misfits" (22). Often marginalised in society, feeling as if their power and control over dominant structures is non-existent, these publications offer an opportunity to make themselves visible and stake a claim in the world through their personal experiences and individual interpretations of the society around them. A particular genre of zine called the personal zine, more commonly known as the 'perzine', is a type of zine that outweighs the subjective over the objective and places the utmost importance on personal interpretation. In other words, perzines aim to express pure honesty on the part of the zinemaker. This often is shown through the rebellion against polished and perfect writing styles in favour of the vernacular and handwritten. The majority of the content of perzines aims to narrate the personal and the mundane, recounting everyday stories as an attempt to shed light on the unspoken. Perzines are often referred to as "the voice of democracy" (Duncombe 29), a way to illuminate difference while also sharing common experiences of those living outside of society, all within the comfort of their bedroom.

With personalisation remaining at the forefront of zine culture as a way to highlight individuality and otherness, the personalisation of political beliefs makes up a large majority of the content present within perzines. In a bid to "collapse the distance between the personal self and the political world" (Duncombe 36), zinemakers highlight the relation between the concept of the 'everyday loser' and the wider political climate they are situated within. As stated, the majority of zinemakers operate outside of mainstream society, so by inserting their own beliefs into the wider political space, they are allowing the political to become personal. This achieves a rebuttal towards dominant institutions through active alienation, revealing the individual interpretation of policies present and situating them in a highly personalised context. This practice of personalising the political also links to the deep yearning zinemakers have for searching for and establishing authenticity within their publications. Authenticity in this context is described as the "search to live without artifice, without hypocrisy" (Duncombe 37). The emphasis is placed upon unfettered reactions that cut through the contrivances of society. This can often be seen in misspelled words, furious scribbling and haphazard cut-outs with the idea of professionalism and perfection being disregarded in favour of a more enthusiastic and raw output. The co-editor of Orangutan Balls, a zine published in Staten Island, only known as Freedom, speaks of this practice of creation with Duncombe, "professionalism – with its attendant training, formulaic styles, and relationship to the market – gets in the way of freedom to just 'express'" (38). There is a deliberate dissent between the ideas of a constructed and packaged identity by the incorporation of nonsensical elements that seek to be seen as an act of pure expression.

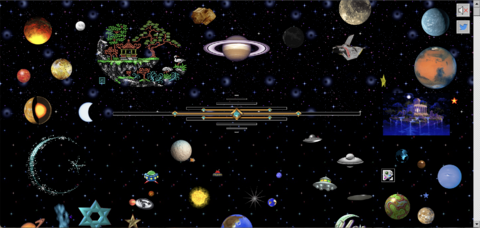

As stated in the introduction to this paper, personal webpages and blogs stand in as the digital equivalent of a perzine. In the mid 1990s, a user's homepage served as an introduction to the creator of the site, employing the personal as a tool to relate to their audience. The content of personal pages, not unlike zines, contained personal anecdotes and narrated individual experiences of their cultural situation from the margins of society. While zines adopted cut-and-paste images and text as their aesthetic style, websites demonstrated their vernacular language through the cut-and-pasting of sparkling gifs and cosmic imagery as a form of personalisation. "To be blunt, it was bright, rich, personal, slow and under construction. It was a web of sudden connections and personal links. Pages were built on the edge of tomorrow, full of hope for a faster connection and a more powerful computer." (Lialina and Espenschied 19) Websites were prone to break or contain missing links which cemented the amateurish approach of the site owner. The importance fell on challenging the very web architectures that were in place, pushing the protocols to the limit to test boundaries as an act of resistance. This resistance is mentioned again by Olia Lialina in a 2021 blog post where she articulates to users interested in reviving their personal homepage: "Don't see making your own web page as a nostalgia, don't participate in creating the 'netstalgia' trend. What you make is a statement, an act of emancipation. You make it to continue a 25-year-old tradition of liberation." These homepage expressions can also be seen as a far cry from the template-based web blogs such as Wordpress, Squarespace or Wix which currently dominate the more standardised approach to web publishing in our digital landscape.

Zines also act as a method of escapism or experimentation. Within the confines of the publication, the writers can construct alternative realities in which new means of identity can be explored. Echoing the cut-and-paste nature of a zine, zinemakers collage fragments of cultural ephemera in a bid to build their sense of self, if only for the duration of the construction of the zine itself. These fragments propose the concept of the complexity of self, separate from the neatly catalogued packages prescribed by dominant ideals of contemporary society. Zines, instead, display these multiplicities as a way to connect with their audience, placing emphasis on the flexibility of identity as opposed to something fixed and marketable.

The search for self is prevalent among contemporary internet users, however, usually this takes the form of avatars or interest-based web forums. Avatars, in particular, allow the user to collage identifying features in order to effectively ‘build’ the body they feel most authentic within. Echoing back to the search for authenticity: "What makes their identity authentic is that they are the ones defining it" (Duncombe 45). Zinemakers aim to use zines as a mean to recreate themselves away from the strict confines of mainstream society and instead occupy an underground space in which this can be explored freely. Echoing this idea, the concept of a personal homepage is frequently embraced as a substitute for mainstream profile-based social media platforms prevalent in the dominant culture. Instead of conforming to a set of predetermined traits from a limited list of options, personal homepages offer the chance to redefine those parameters and begin anew, detached from the conventions of mainstream society.

In short, both zines and homepages become a space in which people can experiment with identity, subcultural ideas, and their relation to politics, to be shared amongst like-minded peers. This act of sharing creates fertile ground for a wider network of individuals with similar goals of reconstructing their own identities, while also encouraging the formulation of their own ideals from the shared consciousness of the community. While zines are the fruit of individuals disenfranchised from the wider mainstream society, they become a springboard into larger groups merging into a cohesive community space.

Building and Sharing the Network

Amongst the alienation felt from being underrepresented in the dominant societal structures, it comes as little surprise that zinemakers often opt for creating their own virtual communities via the zines they publish. In an interview with Duncombe, zinemaker Arielle Greenberg stated "People my age... feel very separate and kind of floating and adrift", this is often counteracted by integrating oneself within a zine community. Traditionally within zine culture, this takes the form of letters from readers to writers, and reviews of other zines that become the very fabric, or content, of the zine themselves. This allows the zine to transform into a collaborative space that hosts more than a singular voice, effectively invoking the feeling of community. This method of forming associations creates an alternative communication system, also through the practice of zine distribution itself. For example, one subgenre of zines is aptly named 'network zines', and their contents entirely comprise reviews of zines recommended by their readership.

This phenomenon is exemplified in the establishment of web rings online. Coined in 1994 by Denis Howe's EUROPa (Expanding Unidirectional Ring of Pages), the term 'web ring' refers to a navigational ring of related pages. While initially, this practice gained traction for search engine rankings, it evolved into a more social context during the mid-1990s. Personal homepages linked to the websites of friends or community members, fostering a network of interconnected sites. In a space in which zinemakers are in opposition to the dictated mode of media publishing, the web ring offers an alternative way of organising webpages as curated by an individual entity, devoid of hierarchy and innate power structures from an overarching corporation, and places the power of promotion into the hands of the site-builders themselves, and extends to the members of the wider community.

The importance of community, or the more favoured term, network, within the zinemaking practice is held in high regard. Due to its non-geographical nature or sense of place, the zines themselves act as a non-spatial network in which to foster this community. Emulating this concept of the medium as the community space itself, online communities also tend to reside within the confines of the platforms or forums that they operate within. For example, many contemporary internet communities dwell in parts of preexisting mainstream social media platforms such as Discord or TikTok, however, their use of these platforms is a more alternative approach than the intended use prescribed by the developers. Primarily using the gaming platform Discord as an example, countercultural communities create servers in which to disseminate and share resources through building topics within the server to house how-to guides and collect useful links to help facilitate handmade approaches to computational publishing practices. The nature of the server is to promote exchange and to share opinions on a wide array of topics, ranging from politics to typographical elements. These servers are typically composed of amateur users rather than professional web designers, fostering an environment where the swapping of knowledge and skills is encouraged. This continuous exchange of information and expertise creates a common vernacular, a shared language, and a set of practices that are distinct to the community. This not only develops the knowledge made available but also strengthens the bonds within the community, as members rely on and support one another in their collective pursuit of a more democratised digital space. In an online social landscape in which the promotion of self remains at the forefront, this act of distribution of knowledge indicates the existence of a participatory culture as opposed to an individualistic one, all united in shared beliefs and goals.

As zinemakers often come from a place of disparity or identify as the other (Duncombe 41), it is precisely this relation of difference, that links these zine networks together, sharing both their originality but also their connectedness through shared ideals and values. Through this collaborative approach, "a true subculture is forming, one that crosses several boundaries" (Duncombe 56). This method of community helps propagate both individualities while simultaneously sharing the very amongst peers, simultaneously allowing their own content to gain the same treatment in the future.

The FOSS movement present in feminist servers also speaks to the ethics of open source software and the free movement of knowledge between users. FOSS, or Free Open Source Software champions transparency within publishing allowing users the freedom to not only access the code but also enact changes to it for their own use (Stallman 168). In Adele C Licona’s book, Zines in Third Space, she also acknowledges the use of bootlegged material: "The act of reproduction without permission is a tactic of interrupting the capitalist imperative for this knowledge to be produced and consumed only for the profit of the producer; it therefore serves to circulate knowledge to nonauthorized consumers" (128). This manner of making stems from a culture of discontent against dominant power structures that control what and how that media is published. Zines are an outlet to express this discontent under their own restrictions and method of reaching their readers while uniting with a wider network of publishers doing the same.

Though zines exist on the fringes of society, their core concerns resonate universally throughout the zine network: defining individuality, fostering supportive communities, seeking meaningful lives, and creating something uniquely personal. Zines act as a medium for a coalitional network that breeds autonomy through making while actively encouraging the exchange of ideas and content. Dan Werle, editor of Manumission Zine states his motivations for zines as a medium for his ideas: "I can control who gets copies, where it goes, how much it costs, its a means of empowerment, a means of keeping things small and personal and personable and more intimate. The people who distribute my zines I can call and talk to... and I talk directly to them instead of having to go through a long chain of never-ending bourgeoisie" (Duncombe 106). With this idea of control firmly placed in the foreground for zinemakers, these zines' aesthetic frequently reflects this, with the hands of the maker is evident in the construction of the publication through handwriting and handmade creation. The importance of physically involving the creator in the process of making zines demonstrates the power the user has over the technological tools used to aid the process, closing the distance between producer and process. Far from only addressing the ethics of the DIY ideals abstractly, zines become the physical fruits of an intricate process, thus encouraging others to get involved and do the same.

Paralleling the materiality of the medium, feminist servers emphasise the technology needed to build and host a server. Using DIY tools such as microcontrollers and various modifications to showcase the inner workings of an active server, the temporal nature of the abstract server is revealed. In this, the vulnerabilities of the tool are also exposed, microcontrollers crash and overheat, de-fetishising the allure of a cloud-based structure, thus, once again bridging the gap between the producer and the process.

Additionally to the question of labour practices in the dominant society, the concept of mass consumption is of real concern to those involved in zine culture. In the era of late capitalism, society has swiftly shifted towards mass-market production, leading to a surge in consumerism. Once a lifestyle made solely available to the wealthy upper classes, mass production of everyday commodities has democratised consumption, making products widely available through extensive marketing to the masses. Historically, consumers felt a kinship with products due to their handmade quality, however, this has diminished in the current market substantially, instead fetishising the hordes of cheaply made objects under the guise of luxury.

Zines are an attempt to eliminate this distance between consumer and maker by rejecting this prescribed production model. Celebrating the amateur and handmade, zines reconnect the links between audience and media through de-fetishising elements of cultural production and revealing the process in which they came to be. Yet again, using alienation as a tool, zinemakers reject their participation in the dominant consumerist model and instead opt for active engagement in a participatory mode of making and consuming. The act of doing it yourself is a direct retaliation to how mainstream media practices are attempting to envelope its audiences, through arbitrary attempts at representation, "because the control over that images resides outside the hands of those being portrayed, the image remains fundamentally alien" (Duncombe 127).

This struggle for accurate representation speaks back to some of the concepts stated in the first part of this paper, namely, how identity is formed and defined. With big-tech corporations headed solely by cisgender white men (McCain), feminist servers aim to diversify the server through their representation of the non-dominant society by sharing knowledge freely. Information is made more widely accessible for marginalised groups beyond the gaze of the dominant power structure and for those with less stable internet connections usually overfed with the digital bloat that accompanies mainstream social platforms. By sharing in-depth how-to guides for setting up their own servers, these platforms not only democratise the internet but also empower individuals to build and sustain more grassroots communities. This accessibility encourages a shift away from reliance on mainstream big-tech corporations, fostering a more inclusive and participatory digital landscape. By enabling users to take control of their own online spaces, these servers promote autonomy, privacy, and a sense of collective ownership.

Zines, similarly, propose an alternative to consumerism in the form of emulation, by encouraging the participatory aspect of zine culture through knowledge sharing, and actively supporting what would usually be seen as a competitor in the dominant consumer culture, readers are encouraged to emulate what they read within their individual beliefs creating a collaborative and democratic culture of reciprocity. The very act of creating a zine and engaging in DIY culture generates a flow of fresh, independent thought that challenges mainstream consumerism. By producing affordable, photocopied pages affording everyday tools, zines counter the fetishistic archiving and exhibition practices of the high art world and the profit-driven motives of the commercial sector: "Recirculated goods reintroduce commodities into the production and consumption circuit, upsetting any notions that the act of buying as consuming implies the final moment in the circuit." (Licona 144) Additionally, by blurring the lines between producer and consumer, they challenge the dichotomy between active creator and passive spectator that remains at the forefront of mainstream society. As well as de-fetishising the form of a publication, they present their opposition and dissonance by actively rejecting the professional and seamless aesthetics that more commercial media objects tend to possess.

This jarring nature of rough and ready against progressively homogenous visuals demands the audience's attention and reflects the disorganisation of the world rather than appeasing it. Commercial culture isolates one from reciprocal creativity through its black-boxing of the process, while zines initially employ alienation to later embrace one as a collaborative equal. The medium of zines and feminist servers isn't merely a message to be absorbed, but a suggestion of participatory cultural production and organisation to become actively engaged in.

Conclusion

From the connections outlined above, the exploration of DIY computational publishing practices reveals significant parallels to the formation of zine culture, both serving as mediums for personal expression, community building, and resistance against dominant societal norms. By examining personal homepages, web rings, and feminist servers, this paper demonstrates how these digital practices echo the democratic and grassroots ethos of traditional zines. These platforms not only offer individuals a space to construct and share their identities but also foster inclusive communities that challenge mainstream modes of production and consumption.