Toward a Minor Tech:Miln500

Between philosophy of mind and the planetary

Alasdair Milne

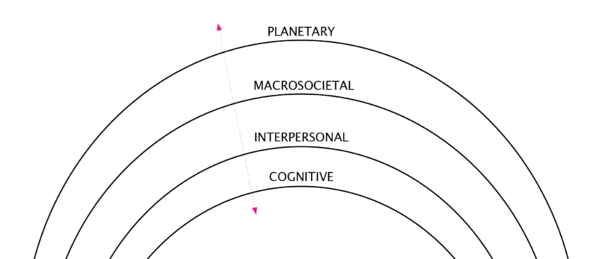

Big Theories about ‘advanced technologies’ (Serpentine R&D Platform, 2020) are burdened by ambiguities of scale. A tendency toward invoking grander macrolevels of ‘planetary computation’ lies in one direction (Hui, 2020). The zoomed-in investigation that characterises philosophy of mind, and its technological equivalents, operates in the other (Metzinger, 2004; Gamez, 2018) accompanied by dense metaphysical perplexities. A maximally noncontroversial view of this scalar setup might look like this (see fig. 1).

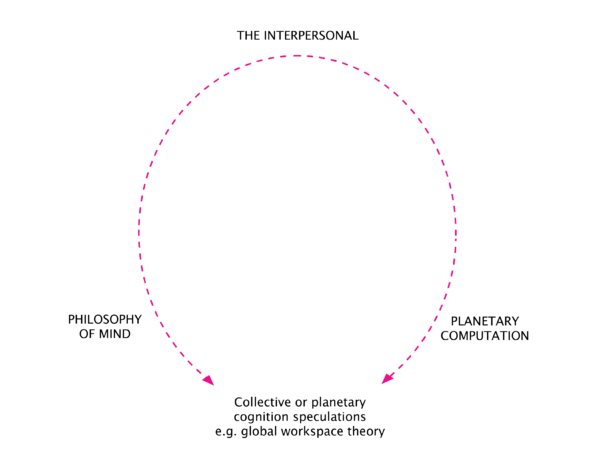

Sometimes the macroscopic and the minute are horseshoed into speculations of collective or planetary-scale cognition (for example VanRullen and Kanai’s ‘global workspace theory’) to compound their urgencies. Such perspectives complicate a straightforward linear view of scale (see fig. 2).

Perhaps these tendencies come from seeing (particularly art-adjacent) technologies and outputs as artefacts to be evaluated in postproduction rather than a distributed and simultaneous field of research & development. But might there be a different level of granularity from which we can build theories of human-computational interdependence? Hannah Arendt posits that human activity is situated in the interdependent field of ‘the space of appearances’ in which thought and deliberation take place as common activities. Here, our world is understood as partly ‘a composition of human artifice’ built together through ‘work’ at the scalar level of the ‘interpersonal’ (Hayden, 2015: 754). The ‘world’, in this view, is always implicated in human relations. This is not to say that we don’t engage in analysis across scales, but rather that we can share a ground with such technology and it’s developmental contexts from where to begin an inquiry.

If we adopt this Arendtian framing the barrier to access then becomes a practical one rather than an ontological impasse. If we want to understand technological development at the scale of the conglomerates (which is vital work) we might seek permission to access their personnel and environs (Jaton, 2021) engaging the toolkit of science and technology studies. But if we are interested in how artists’ systems stand to operate as blueprints for alternative (or ‘minor) technologies, we should seek the hospitality instead of artists themselves, and the institutions that sometimes house the most intensive technical research practices. These ‘minor’ artists’ projects act as subsystems (or countersystems) within a corporate dominated landscape of technical R&D, or what Meadows calls a ‘leverage point’ which can initiate broader change. Here then we zoom out again, from mapping the artist’s system as delimitable, to situating each as an enactive subsystem within a broader systemic landscape. Remembering that the action takes place at the interpersonal level, though, should give us hope that change can be leveraged upscale.