Toward a Minor Tech:Kir

Leaking digital scale – a trio of artistic strategies

This writing briefly presents a collection of three artistic scenes unfolding in or around the peripheries of minor tech. With particular attention to the diverse qualities at play, the cases all aim to downscale technology to a graspable level. Regarding the examples as strategies for altering digital scales, I suggest the artworks as productive lenses to critically examine the dimensions of large-scale digital platforms.

Scene 1: On line

A left-aligned list of words is set in a bold black and almost illegible type. These are the names of the artists. Listed underneath are classical blue-lettered hyperlinks. The page contains nothing more than this: names in bold, accompanied by blue plane links (fig 1).

The digital platform Cosmos Carl presents a website and framework with links to artistic initiatives that appropriate existing commercial platform tools. Amongst the works are projects that modify publicly accessible surveillance cameras (Someplace, somewhere 2020) or another that intentionally misuses Airbnb to present infrastructures of lakes in Georgia (Petits Filous (26,000 Rivers)). While internet pages are commonly visited with a purpose and directed according to expectations (Bucher 2017), Cosmos Carl playfully challenges such online navigation. In this writing, Cosmos Carl contributes with an easily accessible example of artistic intentionally misuse of familiar digital tools.

Scene 2: In the street

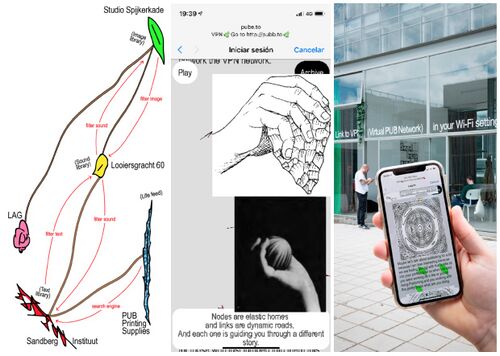

Imagine a locally disrupted online platform: a scattered illustration turns up on a smartphone screen: the circular pattern turns into a globe, then an installation setting, and finally into the shape of a famous cartoon character, all happening along with a twisted interference of sounds and texts.

The scene unfolding describes the features of the emancipatory file server, VPN (Virtual PUB Network) (fig. 2). As an artistic work, VPN served the purpose of mapping and archiving the graduation show of the independent Art and Design university Sandberg Instituut (Amsterdam). However, whereas archives typically help to create order, the visual interfaces of VPN were location-dependent and coded to intentionally disrupt the user's scroll. When introducing VPN, what is of interest is not so much the content but the physically dependent disruption. VPN presents how an interdisciplinary systematic creative strategy may provoke interaction between artists, audience, and spatial surroundings (Bhowmik & Parikka 2021). In extension to the previous example, VPN presents a locally dependent model of misplaced content, disrupted archives, and dysfunctional systems.

Scene 3: At sea

From a mesh of online strategic misusage to locally intended server disruption, the final scene brings us onto the hyper-local solar panel-powered floating context of the art collective 100 Rabbits.

Living, working, and DIY making minor tech tools from their sailboat at open sea, the setup of 100 Rabbits includes everything from generating the power they need to building the programmes they use (drawing, writing, editing, archiving, coding) (Fig. 3). While the programmes developed by 100 Rabbits stand out in a minor tech context, it is with interest in how limitations of access and space are reflected in the works by 100 rabbits. When at sea, bandwidth is limited, electricity scarce, and access to information is dependent on the protocols brought along, effectively the tools and programmes by 100 Rabbits demand logical build-ups (to be disassembled, reassembled, and repaired) (Latour 1994). In this writing, 100 Rabbits bring an inquiry into digital tools, the energy consumed, and the access demanded by commercial digital services. With the two former cases in mind, 100 Rabbits presents a hyper-local scale of how consequences of connectivity limitations and power consumption materialise into creative DIY solutions.

Across scale

From walking and reading to sailing and scrolling, the cases present different qualities of artistic approaches that intentionally are made material, leap into space, or extend out of their digital native sphere. This orientation provides us with a selection of works that expose the processes of known and lesser-known online tools. Through this optic the artistic cases bring forth different strategies to reflect digital scales vertically (Manovich 2012). Here, the concept of scale draws on architectural traditions for systemising space, exemplified by media scholar Berhard Siegert by tracing the development of the three-dimensional grid as an introduction to visual megastructures. Sociology and design scholar Benjamin Bratton further explores visual megastructures by presenting the Stack as a metaphor for digital scale (Bratton 2015). While one should read into this with a critical eye, turning to the example by Bratton exemplifies the complexities brought along in the attempt to comprehend digital scales.

The examples presented in this writing introduce how procedures of twisting or reproducing functions of digital tools may visually or physically reveal the intentions of computational functions and their interfaces (Berlant 2016; Stanfill 2015). Such processes likewise reflect how the language and code of corporate digital platforms could be challenged through activistic and artistic subversions (Cramer & Fuller 2007). The examples were specifically brought together to consider how artistic works can be approached in relation to minor tech solutions and provoke a critical understanding of digital structures.

While many different analytical directions could spring from this point of view, I specifically situate the works into questions of scale in an artistic minor tech context: What may we learn from looking to artistic practices and visualisations concerned with minor tech? And (how) do such creative contributions help to nuance diverse existing understandings of digital platforms? How can we situate artistic platform appropriation as a strategy to critically understand large-scale digital platforms?

Colophon

Bhowmik, S. & Parikka, J. (2021). Memory Machines: Infrastructural Performance as an Art Method, Leonardo Journal MIT press, vol 54

Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*, in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, University of Chicago, USA

Bratton, B. (2015). The Stack. On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge MA, London: MIT Press

Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society 20(1), 30-44.

Cramer, F. and Fuller, M. Interface, in Fuller, M. (2007). (Ed.), Software Lexicon, MIT Press

Latour, B. (1994): On Technical Mediation: Philosophy, Sociology, Genealogy in Common Knowledge, Vol 3, Issue 2, 29-64

Manovich, L. (2012). How to compare one million images? in Berry, D. (ed.), Understanding Digital Humanities, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 249–278

Siegert, B. (2015) Cultural Techniques. Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, New York: Fordham University Press

Stanfill, M. (2015). The interface as discourse: The production of norms through web design, new media & society 2015, Vol. 17

Mentioned art works:

Cosmos Carl, by Frederique Pisuisse and Saemundur Thor Helgason

Petits Filous (26,000 Rivers), Josephine Callaghan, hosted on Airbnb, linked at Cosmos Carl

Someplace, somewhere, Steinunn Önnudóttir, hosted on My Earth Cam, linked at Cosmos Carl

PUB VPN Network by Agustina Woodgate, Miquel Hervas Gomez, Sascha Krischock

100 Rabbits by Rekka Bellum and Devine Lu Linvega

Thanks to Rapahel Bastide for inspiration, to Frederique Pisuisse for Cosmos Carl insights and to PUB VPN for sharing their build instructions made in collaboration with LAG lab for VPN