Toward a Minor Tech:FeministServers5000

nate wessalowski, Mara Karagianni

From Feminist Servers to Feminist Federation

Abstract

Situated within the technofeminist care practices of feminist servers, this text explores the possibilities of feminist federation. Speaking from our collective practice of system administration, we start by introducing Systerserver, laying out the feminist pedagogies that inform our practice of learning and doing together with technologies and the politics of maintenance and care. We then revisit the identity politics of feminist servers as more than safe/r spaces in the cis-male-dominated domain of free/libre and open source software communities. Finally, we reflect on our experiences of building and federating a feminist video platform with the PeerTube software on Systerserver. Facing the techno-social challenges around the protocol of federation and adapting the software alongside our federating practice, we focus on sustainable and care-oriented alternatives to ‘scaling up’ the affective infrastructures of our feminist servers.

We never know how our small activities will affect others through the invisible fabric of our connectedness. In this exquisitely connected world, it's never a question of 'critical mass'. It's always about critical connections. – Grace Lee Boggs

Introduction

In this text we adopt practices of weaving feminist networks of solidarity and care1 in the age of hybrid on- and offline world-making (Haraway 35f). More specifically, we investigate the possibilities of growing into a feminist federation, which accompany the continuation of a feminist video platform project based on the PeerTube software.2 The idea of installing, maintaining and adapting PeerTube in order to build a feminist video platform emerged from the closely knit collaboration of three feminist servers: Anarchaserver,3 Systerserver4 and Leverburns.5 Each of these servers maintains free and open source software that supports different ways of techno-political organizing, from media cloud hosting and tools for the creation of polls, to web hosting for archived cyber-/ technofeminist websites. While some of the sysadmins involved in the installation of PeerTube are or have been involved with two or even all three feminist servers, Anarchaserver and Leverburns mainly supported the project with their tools, while the PeerTube platform was realized through and on Systerserver. For this reason, we focus on the practices around Systerserver and the group of system administrators (sysadmins) actively involved in the PeerTube project. The authors and contributors to this text are women, trans and non-binary people currently part of Systerserver and with different geolocations in Europe. Systerserver organizes mainly through self-hosted mailing lists,6 video calls and other tools that enable shared working sessions and occasional meetings in person during feminist hacking or other, project-related events.

The video platform was set up with the support of a Belgian art fund received in 2021, not as a permanent infrastructure but as an experimental process for sharing artistic videos and live streaming. A year later, when the funded period came to an end, two things became clear: although there was a need from video-makers7 to host their art and content in feminist and community-based environments, we didn’t want to become yet another centralized service infrastructure. Instead, awarded with another grant by a Dutch design fund, we set out to enable other collectives to host their own infrastructures and join a feminist federation of video platforms.

The process of writing about the possibilities of feminist federation started with Systerserver’s participation in the Minor Tech workshop,8 where questions around scalability were discussed and researched. ‘Scalability’ is more than just a descriptive category: it has also been infused with the ethical obligation to facilitate participation (Sterne VII), namely to involve as many people as possible, if not to ‘change the world’. In this sense small scale projects are measured by their potential to finally and eventually ‘grow up’ and ‘become major’. Projects or collectives such as feminist servers, which are understood to be ‘niche’ or ‘small scale’, typically involve a limited number of people, known only within certain counter-publics (Travers) or circles of friends. They are not geared towards profit, nor efficiency, and often work with a (trans)local embeddedness, where geographies and cultures come together in virtual and physical spaces, and therefore they cannot be easily replicated. Starting from our practice of system administration and the embodied experiences of collectively building a feminist video platform, we turn to explore the process ‘from feminist servers to feminist federation’. Based on a technofeminist understanding of the political and gendered aspects of technology, we ask how technologies and protocols of decentralized social media networking and federation9 can facilitate this process. What are the challenges of forming and growing into a feminist federation?

Feminist Servers

Feminist servers are infrastructures for nourishing communities of feminists with an interest in technologies or a digitally mediated, art and/or activist, praxis. They are an embedded techno-social practice, a critical intervention into the human-machine dichotomies, and protagonists of a speculative fiction calling for a feminist internet (spideralex, “Internet Féministe”; Toupin/spideralex). Due to their ‘techno-nature’ they are highly connective, interlinking and forming temporary networks of care and solidarity to exchange knowledge and tools, learn together and become involved with each others’ infrastructure projects.10 The genealogies of feminist servers are not easy to trace as they form ties and intersections with various movements such as cyber- techno- and trans hack feminisms, women-in-tech initiatives, academic fields around network, media and publishing, autonomous tech collectives and network activism, digital commons enthusiasts, the hacker, self-hosting, free/libre and open source software (FLOSS) movements, Do-it-yourself/together (DIY/T) culture, and feminist cybersecurity and self-defense. The motivations behind the formation of feminist servers often stem from the need for spaces in which lesbians, women, non-binary and trans persons, disidentes de género (gender dissidents), and queers can share knowledge about technology and organize themselves. 11

Systerserver is one of the earliest known feminist server collectives. The server was launched in 2005 as an initiative of the GenderChanger Academy (Mauro-Flude/Akama 51) founded and composed by a group of women involved in a squatted Internet Cafe/ Hackerspace in Amsterdam (ASCII) during the late 90s (Derieg). GenderChanger Academy was formed, in early 2000s, to “get more women involved in technology”12 by initiating tech skill-sharing workshops.13 In 2002 the first Eclectic Tech Carnival (/etc) took place – a new format derived from the Amsterdam affiliated network that would enable skill-sharing sessions, workshops and discussions in the shape of self-organized hack meetings across Europe from Croatia to Greece to Serbia, Austria, Romania and Italy.14 During these mostly annual meetings, Systerserver – while often dormant throughout the rest of the year – was activated as a supportive infrastructure for hosting websites, organizing, learning and archiving. When the frequency of the /etc meetings slowed down – partly due to a crisis in identity politics and remediation of trans-hostility and the inclusion of trans persons – new strategies to keep the server active were sought out. By that time, many people had been involved with Systerserver and most of those who had launched the server were no longer actively participating. In 2021 the current group of sysadmins applied for funds to develop a feminist video platform, in order to sustain the feminist server project and the community around it.

Even though in the context of feminist servers a ‘server’ is not a purely technical term, virtual and physical machines are integral to the techno-social practices which constitute feminist servers. The technical infrastructures of Systerserver, Anarchaserver and Lever Burns are either located within shared activist networks on virtual servers, someone’s home or, in the case of Systerserver at mur.at, within a net culture initiative that has a data room. Some of the servers are stable enough to distribute their services, and this allows the servers to depend on each other, sharing their tools while fostering webs of commitment, responsibility and care.

In resonance with other writings on the subject of feminist servers, (spideralex, “internet féministe”, Niederberger, “Feminist Server”, “Der Server ist das Lagerfeuer”, Mauro-Flude/Akama, “A Feminist Server Stack”, Kleesattel) the following passages trace important aspects of the feminist pedagogies that inform the practices of maintaining a server and building a feminist video platform through Systerserver.

Making (safe/r) spaces for feminist and queer communities

The idea of a feminist server is sometimes linked to the concept of safe/r spaces,15 which actively oppose patterns of discrimination, taking intersectional safety needs and trust into account. Feminist servers can become safe/r spaces for queer, trans and women-identified persons who experience patriarchal oppressions and violence, especially in the cis male-dominated realm of information technology and digital infrastructures. Most of the time, feminist servers stay intimate, known to small circles of friends and allies with no explicit or formalized politics of invitation. However, with the PeerTube platform Systerserver opened their affective infrastructure to seek out critical connections with other feminists and collectives with a shared interest in self-managed digital infrastructures away from the exposure to harassment, exploitation and censorship inherent to mainstream platforms.16 During these residencies, we entered into an exchange with the techno-political desires, vulnerabilities and accessibility needs of different modes of inhabiting our feminist video platform. Together with Broken House,17 a community tool for sex-positive artists and porn makers in Berlin, we realized an unlisted and invite-only 24-hours streaming event that showcased a collage of post-porn art, archival material and video clips. The artists felt comfortable hosting a sensitive event on a feminist server, because knowing the people behind the machine, and knowing that the streaming remains unlisted, established a shared trust. Another residency with the design research collective for disability justice MELT18 resulted in an illustrated video about a project called ACCESS SERVER, which included sign language and was published as multiple versions of one video, each with a different set of subtitles.

Feminist critique of FLOSS: Choosing our dependencies19

The PeerTube software that we installed on Systerserver is free software for the creation of video and streaming platforms, which is maintained and developed by the French non-profit Framasoft initiative. PeerTube forms part of FLOSS, an umbrella term for free and open source software such as the Linux kernel, Firefox web browser, NextCloud or Signal Messenger. Freedoms are granted through licenses such as the GPL (General Public License) or, in the case of PeerTube, Affero GPL.20 By circumventing existing proprietary copyright regimes, this allows everyone with the necessary skills to run, study, improve and distribute the software. Feminist servers – whenever we can – run and adapt free and open source software with regards to our specific and embodied needs. Free software aligns politically with feminist servers’ core values, such as sharing knowledge, empowering each other and working against power hierarchies based on gatekeeping, access to resources, tools and knowledge, as it allows them to run the software for themselves and on their machines (see also Snelting/spideralex 4 with reference to Laurence Rassel, Niederberger, “Der Server ist das Lagerfeuer” 7f). This is a form of emancipation from centralized or autonomous tech infrastructures, which are often administered by cis men, which thus challenges the historical attribution of femininity as something in opposition to technology, and the power awarded through technological proficiency (Travers 225, citing Cockburn). Free software therefore allows for bypassing the power monopolies held by tech corporations under the matrix of patriarchal techno-domination. Despite continuous efforts to address the diversity of identities in FLOSS development,21 however, only around 10 percent of contributions in FLOSS stem from women (Bosu/Sultana). These injustices are rooted in interrelated causes that form access barriers, such as sexist bias (Terrell/ Kofink/ Middleton/ Rainear/Murphy-Hill/ Parnin/ Stallings) and toxic behavior paired with the refusal to acknowledge forms of discrimination (‘gender blindness’) given the supposedly open nature of FLOSS projects (Nafus). Feminists have also pointed to factors such as the unequal distribution of care work and unequal wages resulting in an imbalance regarding free time for contributing volunteer work. Many digital infrastructure projects, even though in theory open for anyone to participate, are therefore prone to reinforcing mechanisms of exclusion and power hierarchies alongside intersectional patterns of marginalization (Dunbar-Hester 3f).

Maintenance as Care

Computer science and IT industry culture has tried to distinguish between software development as creative work in contrast to the tedious labor of software maintenance (Hilfling Ritasdatter 156f)22. This distinction also applies to sysadmin work, which is mostly about maintaining, repairing and updating infrastructure and thus shares many characteristics with invisiblized, racialized and feminized care work (Tronto 112-114). The problems of devaluation are rooted within the intricacies of the server-client relationship, as well as the ‘software as service’ or cloud paradigm. The questions “Who is serving whom? Who is serving what? What is serving whom?” lie therefore at the center of the critical practice around feminist servers, which “radically question the conditions for serving and service; they experiment with changing client-server, user-device and guest-host-ghost relations where they can.” (Transfeminist Wishlist).

Practices of care and maintenance within feminist servers must be understood as negotiations of collective responsibility. One important agreement for Systerserver is the no-pressure policy, which allows its sysadmins to participate according to their availabilities and thereby extends the principle of care towards themselves by taking into account the different intersectional precarities that define their situation. Contributions to the maintenance of the machine, and to the social relations around it, entail security upgrades, hardware replacements, backups, data migrations, and attentive documentation. In the case of the Systerserver video platform, this includes adapting the software to the needs of its community and specific use cases, curating new accounts, updating the platform’s code of conduct and communicating changes to the inhabitants of the platform. Nonetheless, the attitude of feminist servers’ work does not comply with the superimposed specters of seamlessness, infinite resources and the nonstop availability of computing.23

Affective Infrastructures

Feminist servers are often described in terms of digital, material and discursive or speculative infrastructures, which ties in many of the above mentioned aspects around making space, looking into issues of safety, trust, access and questions of being served, as well as maintenance and care (Niederberger, “Feminist Server”). Cultural theorist Lauren Berlant writes that “the question of politics becomes identical with the reinvention of infrastructures for managing the unevenness, ambivalence, violence, and ordinary contingency of contemporary existence.” (Berlant 394) To her, building and maintaining infrastructures is a way of doing (techno) politics, as infrastructures shape and organize the social relations that form around them. While critiquing the dismissal of the material nature of ‘cyberspace’, an infrastructural approach can sometimes tilt into prioritizing the technical over the social aspects. This is why some of us understand feminist servers in terms of affective infrastructure, foregrounding acts of community-based maintenance and affective labor. Everyday and mundane repair necessary for when things break down, can – in small and multiple increments – lead to larger changes in knowledge production (Hilfling 168 with reference to Graham and Thrift)

Affective infrastructures suggest a different relation to tools and data, an “added layer of intimacy” (Motskobili 9) based on the collective practice of hosting and adapting software to meet our needs and desires. In reference to the histories of queer resistance and the re-appropriation of the ‘pink triangle’24 by the queer community, Systerserver’s video platform adapted the pink triangle as a deconstructed PeerTube logo: one of its tactics of designing a queer-friendly interface. This also changes the practices of engaging with the infrastructures as a “space that we want to inhabit, as inhabitants, where we make a contribution, nurturing a safe space and a place for creativity and experimentation, a place for hacking heteronormativity and patriarchy.” (Snelting/spideralex 5)

Feminist Federation

After the first phase of the PeerTube platform was implemented on Systerserver and a curated period of try-outs had come to an end, questions regarding the continuation and maintenance of the video platform as well as long-term availability arose. While the response from the resident artists and collectives was very encouraging, growing Systerserver’s video platform into a more visible instance25 did not align with the sysadmin’s capacities, resources, and interests. Thus, instead of taking up more responsibility as a ‘single point of service’ and adopting the naturalized logic of ‘scaling up’, Systerserver decided to explore a different path to nurturing its feminist communities: the formation of a feminist federation. This is an ongoing process that, at the time of writing, has just started to unfold. This text can thus only provide a preliminary outline of what a feminist federation on the basis of the PeerTube software might eventually grow into.

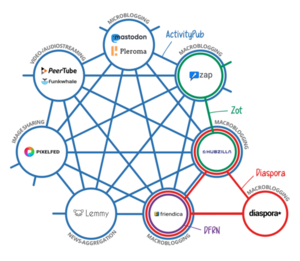

PeerTube is based on the open communication protocol ActivityPub,26 which allows a video platform to connect not just with other PeerTube platforms, but with all social networks and other media instances based on the same protocol. The technosocial agreement behind this is called federation, which is characteristic of the fediverse:27 a decentralized network of currently around 50 different types of social media such as Mastodon (microblogging), Mobilizon (event management), Funkwhale (sound/audio hosting) or Pixelfed (image hosting).28 Through federation, content such as microblogging or files (images, documents, videos) that are hosted on one instance can be accessible from another. All instances within the fediverse are maintained by a collective or individual sysadmins, who can open their infrastructures to a community of participants according to their politics of invitation (e.g. open access or invite-only) and who can adopt or fork29 the software, propose a code of conduct or make design choices for their instance.

The concept of federation originally derives from a political theory of networks in which power, resources and responsibilities are shared between actors, thus circumventing the centralization of authority (Mansoux and Roscam Abbing). When this is implemented within alternative social networks, Robert Gehl and Diana Zulli have argued that it can maintain the local autonomy of all instances while at the same time strengthening the collective commitment to an ethical code fostering connection and exchange. They have linked the politics behind federated social media to the concept of the covenant, a federalist political theory developed by Daniel Elazar (Gehl and Zulli 3). A covenant is an agreement to (self-) governance by a group of people, and it is based on shared ethical choices.31 Participants’ consent is actively and continuously negotiated, which means in the case of the fediverse that instances can freely choose to either leave or join the fediverse by federating with other instances (Gehl and Zulli 4). This capacity for consensual engagement and autonomous boundary setting aligns with feminist servers’ technofeminist desire for autonomous infrastructures and choosing our own dependencies. Not only does PeerTube software as part of FLOSS allow us to create a safe/r space on our machines, but the application of an open protocol such as ActivityPub also establishes a technosocial base that effectively enables growing bonds among different feminist communities. Here connection becomes a consensual choice, not a forced commitment or a default that is hard to reverse. Even after federating with each other, connections can be dissolved (‘defederated’) at any time – for example in the case of irreconcilable safety needs or in the face of diverging values – leaving instances with the ability to self-determine and negotiate their boundaries according to their needs. Their ability to consent is tied to the formation of non-hierarchical bonds that presuppose the absence of undesired dependencies or power relations.

PeerTube has an opt-in federation style, meaning that after a new installation of the PeerTube software, the instance is neither followed by nor following other instances and is therefore only hosting its own inhabitants and contents. In order to federate, the administrators of the instance accept so-called ‘follow requests’, and follow other instances with whom they would like to share content.32 After the initial setup of PeerTube, Systerserver’s community started to look for instances with whom to federate and share their content, but realized that there were hardly any queer or feminist platforms around. Considering that PeerTube and even the fediverse are not widely known and due to their closeness to the cis male-dominated FLOSS communities and the demanding prerequisites for the installation and maintenance, this is not very surprising. However, it has consequences for the feminist appropriation of the principles and technosocial protocols of federation. In order for Systerserver to federate its platform, it is necessary to take on an empowering and pedagogical approach, transcending the retrospective logic of ‘connecting’ something that already exists by growing relational networks of solidarity and care into supporting the making of video infrastructures embedded in other localities.

Looking into this kind of resonance with other communities, Systerserver started to facilitate and participate in setting up two new video platforms:33 one at Ca la Dona, a feminist community center in Barcelona and one with Broken House, the Berlin-based community tool with which Systerserver had already collaborated in the form of a residency when first setting up the PeerTube platform. The installation and federating processes are part of two week-long programs, each carried out together with the local communities.34 Once the platforms are up and federated, they aggregate the content of each community’s platform through the web interface of the other platforms. However, this is only one of the ways in which critical connections between feminist and queer communities can manifest themselves within a feminist federation. Another important aspect is the facilitation of networks of solidarity and care among the participants. These kinds of networks can grow by meeting each other and forming relationships that can facilitate the exchange of knowledges, support, advice and resources. In doing so, this can result in the formation of a covenant of platforms who agree to federate with each other alongside certain core values or upon a shared code of conduct.

Supporting local communities in the endeavors of building up their own technopolitical infrastructures comes with the challenges of meeting other spatial and cultural realities as well as getting to know about different needs tied to the context and motivations behind building a video platform. In the case of Ca la Dona, the local community and space was able to reactivate old hardware (rack servers) donated to the space and install their PeerTube instance on an in-house server.35 However, issues arose with regard to the excessive energy consumption of the old hardware and the lack of a stable network interface to the outside. In the case of Broken House, which is the coming collaboration, challenges that lie ahead range from choosing a hosting provider for renting a server, to ensuring that the local community can establish connections with people who are motivated to learn and support with administering the server.

While adapting PeerTube software to our community needs, we faced two shortfalls: one was the lack of group accounts, and the other the unchecked power of administrators and moderators over the inhabitants’ data and invitation to federate. Group accounts are valuable to communities, especially the most vulnerable ones such as feminist, queer and trans communities, as it enhances anonymity within a group and reduces toxic attacks directed to single persons. ActivityPub has yet to implement accounts for a group of people.36 Christine Lemmer-Webber, lead author of ActivityPub protocol, notes “that the team predominantly identified as queer, which led to features that help users and administrators protect against ‘undesired interaction’.”37 However ActivityPub and PeerTube are still centered around individual creators and do not yet support group accounts or community video channels, even though the community has been asking for this since 2018.38

In his book Platform Socialism, James Muldoon suggests that we should shift our concerns from “privacy, data and size”, and claim the “power, ownership and control” over our digital media (Muldoon 2). Whereas in the case of federated social networks there is an empowering dimension at play as activists start to collectively govern part of the infrastructure, there is an asymmetric power balance between inhabitants and administrators/moderators when it comes to owning our data. Fediverse allows for a social design of privacy by putting effort into providing finer moderation tools (Mansoux and Roscam Abbing 132-33), such as visibility preferences for posts and defederation by blocking other instances. However, by default sysadmins and moderators have access to unencrypted user messages and databases as well as graphs of interactions (Budington). This is why Sarah Jamie Lewis has called for a distribution of powers, such as a privacy preserving persistence layer removed from any specific application:

You need that first persistence layer to be communal and privacy preserving to prevent any entity being in a position do something like all the DMs on this instance are readable by whoever admins it.

Recent technological developments of encrypted social networks (a hybrid of federation and peer-2-peer) have emerged and are in the making.40 However, technical contributions in federated social networks remain dominated by a specific group of developers, still missing out in terms of gender and ethnic diversity.41 This may account for why the design of the more widespread federated social networks falls short in aspects of privacy and group accounts, whose importance for community safety have not been addressed yet.

From where we stand now and according to the resources available to us, we choose to focus on the social and technopolitical aspects of caring for our infrastructures and growing into a feminist federation, rather than on the development of the software itself. This means that we make do with the existing open protocol of ActivityPub and the PeerTube software, which we can adopt in accordance with our basic needs for free software, autonomous safe/r spaces and the possibilities for sustainably growing our affective infrastructures. Nevertheless, we also engage in a closer investigation of the development and debates of and around PeerTube and ActivityPub and their open source communities, such as in writing this text.

Outro: How not to scale but resonate

The anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has criticized the prevalent conceptualization of ‘scalability’ by pointing out how projects of scale are often implicated in extractivist, colonialist and exploitative modes of production. She defines scalability as characteristic of something that can expand without transforming and is therefore prone to rendering surrounding landscape and nature (including humans) into mere resources (Tsing “Nonscalability” 507). Thus the idea of scalability is not compatible and even in conflict with the situated, power-sensitive and non-exploitative approaches that characterize feminist servers. And while the values of feminist servers lie precisely in their nonscalable qualities, accounting for the embodied needs of people, landscapes and machines, this does not make them isolated ‘niche’ phenomena. Instead feminist servers since the beginnings have set out to explore nonscalable ways of forming networks of solidarity and care among themselves and beyond. Among those, this text has explored the beginnings of a feminist federation as one possible mode of reaching out and growing – not in the distorted sense of infinite progress, but in sustainable and careful ways. In the face of both structural and particular precarities, this implies getting to know and strengthening each others’ communities in the process of federating and creating fruitful ways of exchange and mutual support. The roles that Systerserver takes in facilitating local communities before, during and after the installation of PeerTube, are part of a collective learning process, which informs our feminist pedagogies.

This shared effort may at some point result in a covenant with a more explicitly shared set of values articulated from within the feminist federation and in collaboration with all the communities that participate in it. It will reflect a process of learning to maintain feminist infrastructures according to the local needs and context from which each community comes together. This is what we may call the resonance of queer and feminist voices, facilitating and hearing each other out in order to find common ground in recognizing the differences. We do this by engaging in political debates and by establishing critical connections with allies, continuing our efforts of caring for our feminist digital infrastructures now and in the long run. Systerserver’s ongoing experimentation with the possibilities of a feminist federation can be understood as the interplay between a social and artistic embodiment of a technological protocol that allows content to be streamed, accessed and exchanged between servers. But while the idea behind most social networking protocols is to establish as many connections as possible, feminist federation embraces a more hesitant and critical mode of connecting, and is only interested in federating with others who share our approach of queering technopolitics.

As a collaborative effort to think and speak about some of the intricacies of caring for machines and bodies in the context of feminist servers, this text can only be an articulative exercise. It will accompany but never capture or represent what it is that some of us are doing or how some of us find meaning in what it is we are doing. Instead it becomes part of our collective processes of developing and sharing knowledge and skills around feminist appropriations of free software, technopolitical tools for organizing, and feminist pedagogies. Feminist servers adopt the ideas of FLOSS and other tech communities where disempowered users can become (code) contributors, system admins and hackers by choosing their own dependencies and enabling communities into becoming infrastructure makers and maintainers. In experimenting and engaging with modes of feminist federation, we aim to reach out and share our knowledges, thereby becoming a little more visible. Doing so also allowed us to document and reflect on our practice and to speculate and make space for questions and articulations that might guide further paths and developments. Feminist servers and modes of federation can support us in our needs and amidst the “ruins of capitalism” (Tsing, “End of the World”). They make space for ways of relating differently to each other and (with) technology.

Acknowledgements

The following sysadmins from a network of feminist servers contributed to the collaborative writing process and previously published versions: ooooo - transuniversal constellation, vo ezn - sound && infrastructure artist, Mara Karagianni - artist and software developer, nate wessalowski - technofeminist researcher and doctoral student.

English correction by Aileen Derieg.

Authors and contributors form part of a wider ecosystem of techno-/ cyberfeminists, sysadmins and allies, mostly across Europe and Abya Yala, South America.

Many thanks to the organizers and reviewers of Minor Tech in giving us the chance to articulate our praxis.

Notes

1 Formulation following spideralex, "Feministische Infrastruktur" 59.

2 https://tube.systerserver.net.

3 https://www.anarchaserver.org/.

5 http://terminal.leverburns.blu.

6 The following lists are part of the extensive network of feminist servers: Adminsysters, https://lists.genderchangers.org/mailman/listinfo/adminsysters; Eclectic Tech Carnival, https://lists.eclectictechcarnival.org/mailman/listinfo/etc-int; Femservers, https://lists.systerserver.net/mailman3/lists/femservers.lists.systerserver.net/.

7 Videomakers who got in touch with Systerserver’s video platform via the residencies and the TransHackFeminism Covergence, https://zoiahorn.anarchaserver.org/thf2022/bienvenides-a-la-convergencia-transhackfeminista-2022/.

8 Minor Tech workshop facilitated by Transmediale 2023, https://aprja.net//announcement/view/1034.

9 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_social_network and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_software_and_protocols_for_distributed_social_networking.

10 For an extensive list of feminst servers, see https://alexandria.anarchaserver.org/index.php/You_can_check_some_of_their_services_in_this_section.

11 While some feminist infrastructure projects are open to feminists of all genders, most of them - like Systerserver - are shaped by a separatist approach that excludes cis men from participating. We do this in order to create spaces where we don’t have to constantly worry about being gendered as ‘other to men’. Many of the ways we relate to and behave around cis men are deeply rooted in our cultural memories: counteracting male violences or carelessness, feeling pressured into proving to be ‘as good as men’, falling back into patterns of serving or pleasing men or just not taking the space due to fear of pushback. Excluding cis men is of course not a sufficient criteria for creating spaces without patriarchal violence but our experiences have taught us that it can be very liberating. Besides, cis men have many opportunities to engage in mixed/all gender tech related activism.

12 https://www.genderchangers.org/faq.html.

13 The adapter they are named after is a device that changes the ascribed ‘orientation’ of a port – both stressing the always gendered aspects of technology as well as the urgent need to reverse and counteract the cis male domination of technological domains.

14 More information about the /etc and past events see https://eclectictechcarnival.org/ETC2019/archive/.

15 The concept of safe/r spaces dates back to the heyday of the second wave of feminism when lesbians, trans people and women started organizing within and through woman only spaces. It has since been adopted to online spaces, see Katrin Kämpf, “Safe Spaces”.

16 About video monetization and censorship on YouTube, see Mara Karagianni, “Software As Dispute Resolution System: Design, Effect and Cultural Monetization”.

17 https://tube.systerserver.net/a/broken_house/video-channels.

18 https://www.meltionary.com/.

19 Formulation following “A Feminist Server Manifesto”.

20 Affero GPL has an extra provision that addresses the use of software over a computer network (such as a web application), and requires the full source code be accessible to any network user of the AGPL-licensed software. “Affero General Public License”. In Wikipedia, accessed June 4, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affero_General_Public_License.

21 See, e.g., the artist project “Read The Feminist Manual” about gender discrimination in FLOSS, an online governance research organized by the Media Enterprise Design Lab of Boulder University of Colorado, accessed on May 21, 2023, https://excavations.digital/projects/read-feminist-manual/.

22 In chapter III on Maintenance, Hilfling Ritasdatter critically contests the differences between unproductive labor, which sustains life, and creative work that produces and changes the world, as those have been articulated by various political theorists such as Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (Hilfling Ritasdatter 149), See also the distinction betweendevelopment and maintenance in the “Manifesto for Maintenance Art” from 1969 by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, talked about in the context of feminist servers by Ines Kleesattel, 184f.

23 See also A Feminist Server Manifesto where it states that “A feminist server... tries hard not to apologize when she is sometimes not available.”

24 “Pink triangle”, in Wikipedia, last modified June 1, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pink_triangle.

25 Instance is the term for a particular installation of a software on a server.

26 “What is ActivityPub”, accessed May 26, 2023, https://docs.joinmastodon.org/#fediverse.

27 The word ‘fediverse’ is a lexicon blend of federation and universe, “Fediverse”, in Wikipedia, last modified May 27, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fediverse.

28 An easy way to explain federated media is through the concept of email providers, see https://docs.joinmastodon.org/#federation.

29 In FLOSS environments, forking describes the copying, modification and development of a software in a way that differs from the previous creators’ or the maintainers’ projects and is often accompanied by a splitting of communities.

30 How the Fediverse connects, image creators Imke Senst, Mike Kuketz, licenses Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, source https://social.tchncs.de/@kuketzblog/107045136773063674.

31 Convenantal federation is distinguished from contract federation, which is based on legal texts and institutional laws.

32 This is different from Mastodon, where a kind of convenant is in place. Here, instances are federated per default with other instances which commit to a shared set of rules such as moderation against racism, sexism, trans- and homophobia or daily backups of all data and posts. Accessed May 26, 2023, https://joinmastodon.org/covenant.

33 Systerserver received financial support for this undertaking as part of the 360 Degrees of Proximities project by the Dutch Creative Industries Funds.

34 For more details about the collaboration, see https://mur.at/project/syster360/.

35 In house server means that is physically located in a space vs a cloud server, accessed June 3, 2023, https://www.acecloudhosting.com/blog/in-house-server-vs-cloud-hosting/.

36 Looking into the development history from OStatus and its implementation in previous decentralized social networks, the group feature was dropped in 2013. From a user’s comment inthe pump.io social network code repository we read:

“This is a major drawback since the migration. We were using the ‘koumbitstatus’ group to do status updates for our network in a decentralised way, on some servers outside of our main infrastructure. This functionality is now completely gone.

While I think now that we shouldn’t have relied on identi.ca for that service, I was expecting the ‘federation’ bit to survive the migration: I post those notices from my home statusnet server, and the fact that those don't communicate at all anymore makes this a very difficult migration. This will clearly make us hesitant in using pump.io or any other federated protocol (as opposed to say: a simple html page with rss feeds) to post our updates.”

Accessed on May 28, 2023, https://github.com/pump-io/pump.io/issues/299.

37 In January 2018, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) published the ActivityPub standard as a Recommendation.

38 The request for group accounts has been open on the GitHub code repository of PeerTube since 2018, and there is a long thread of users requesting this feature. In one of the comments we read: "IMHO it would be a good thing to promote collaborative creation. It would be another way to offer something different from Youtube (which is centered on individuals)." Accessed on May 28, 2023, https://github.com/Chocobozzz/PeerTube/issues/699.

39 Sarah Jamie Lewis, https://pseudorandom.resistant.tech/federation-is-the-worst-of-all-worlds.html.

40 See Bluesky (https://blueskyweb.xyz/blog/3-6-2022-a-self-authenticating-social-protocol) and Manyverse (https://www.manyver.se/).

41 Looking at the forum of ActivityPub, most people who have profile pictures and are the most active seem to be white men, https://socialhub.activitypub.rocks/.

Works cited

A Feminist Server Manifesto. 2014, https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit_afterlife.xhtml.

A Wishlist for Trans*Feminist Servers. 2022, https://etherpad.mur.at/p/tfs.

Berlant, Lauren. "The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times". Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 3 (June 2016): 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989.

Bosu, Amiangshu, and Kazi Zakia Sultana. ‘Diversity and Inclusion in Open Source Software (OSS) Projects: Where Do We Stand?’ In 2019 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement (ESEM), 1–11. Porto de Galinhas, Recife, Brazil: IEEE, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/ESEM.2019.8870179.

Budington, Bill. ‘Is Mastodon Private and Secure? Let’s Take a Look’. Electronic Frontier Foundation, 16 November 2022. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/11/mastodon-private-and-secure-lets-take-look.

Cockburn, Cynthia. Machinery of Dominance: Women, Men, and Technical Know-How. Pluto Press, 1985.

Derieg, Aileen. "Tech Women Crashing Computers and Preconceptions". Instituant Practices - Transversal Texts, July 2007. https://transversal.at/transversal/0707/derieg/en.

Dunbar-Hester, Christina. "Hacking Technology, Hacking Communities: Codes of Conduct and Community Standards in Open Source". MIT Case Studies in Social and Ethical Responsibilities of Computing, no. Summer 2021 (10 August 2021). https://doi.org/10.21428/2c646de5.07bc6308.

Gehl, Robert W., and Diana Zulli. "The Digital Covenant: Non-Centralized Platform Governance on the Mastodon Social Network". Information, Communication & Society (15 December 2022): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2147400.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures: Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices. Duke University Press, 2016.

Hilfling Ritasdatter, Linda. Unwrapping Cobol: Lessons in Crisis Computing. Malmö University, 2020.

Jamie Lewis, Sarah. Queer Privacy Essays From The Margins Of Society, 2017. https://ia600707.us.archive.org/7/items/Sarah-Jamie-Lewis-Queer-Privacy/Sarah</nowiki> Jamie Lewis- Queer Privacy.pdf.

Kämpf, Katrin M. ‘Safe Spaces, Self-Care and Empowerment – Netzfeminismus im Sicherheitsdispositiv’. FEMINA POLITICA – Zeitschrift für feministische Politikwissenschaft 23, no. 2 (17 November 2014): 71–83. https://doi.org/10.3224/feminapolitica.v23i2.17615.

Karagianni, Mara. "Software As Dispute Resolution System: Design, Effect and Cultural Monetization". Computational Culture, no. 7 (21 October 2019). http://computationalculture.net/software-as-dispute-resolution-system-design-effect-and-cultural-monetization/.

Kleesattel, Ines. "Situated Aesthetics for Relational Critique On Messy Entanglements from Maintenance Art to Feminist Server Art". In Aesthetics of the Commons, edited by Cornelia Sollfrank, Felix Stalder, and Shusha Niederberger. Diaphanes, 2021.

Mansoux, Aymeric, and Roel Roscam Abbing. "Seven Theses on the Fediverse and the Becoming of FLOSS". In The Eternal Network: The Ends and Becomings of Network Culture, 124–40. Institute for Network Cultures and Transmediale, 2020.

Mauro-Flude, Nancy, and Yoko Akama. "A Feminist Server Stack: Co-Designing Feminist Web Servers to Reimagine Internet Futures", 2022.

Motskobili, Mika. ‘LEVER BURNS’. Piet Zwart Institute, Willem de Kooning Academy, 2021. https://project.xpub.nl/lever_burns/pdf/Ezn_LeverBurns.pdf.

Muldoon, James. Platform Socialism: How to Reclaim Our Digital Future from Big Tech. Pluto Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv272454p.

Nafus, Dawn. "'Patches Don’t Have Gender': What Is Not Open in Open Source Software". New Media & Society 14, no. 4 (June 2012): 669–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811422887.

Niederberger, Shusha. "Feminist Server – Visibility and Functionality – Creating Commons", 2019. https://creatingcommons.zhdk.ch/feminist-server-visibility-and-functionality/index.html.

———. "Der Server Ist Das Lagerfeuer. Feministische Infrastrukturkritik, Gemeinschaftlichkeit und das kulturelle Paradigma von Zirkulation in Digitaler Infrastruktur". preprint, 2021.

Snelting, Femke, and spideralex. "Forms of Ongoingness". Interview by Cornelia Sollfrank, 16 November 2016.

spideralex. "Pas d´internet féministe sans serveurs féministes". Interview by Claire Richard, 2019. https://pantherepremiere.org/texte/pas-dinternet-feministe-sans-serveurs-feministes/.

———. "Feministische Infrastruktur aufbauen: Helplines zum Umgang mit geschlechtsspezifischer Gewalt im Internet". In Technopolitiken der Sorge, edited by Christoph Brunner, Grit Lange, and nate wessalowski. transversal, 2023.

Sterne, Jonathan, ed. The Participatory Condition in the Digital Age. Electronic Mediations 51. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Terrell, Josh, Andrew Kofink, Justin Middleton, Clarissa Rainear, Emerson Murphy-Hill, Chris Parnin, and Jon Stallings. "Gender Differences and Bias in Open Source: Pull Request Acceptance of Women versus Men". PeerJ Computer Science 3 (1 May 2017). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.111.

Toupin, Sophie and spideralex. "Introduction: Radical Feminist Storytelling and Speculative Fiction: Creating New Worlds by Re-Imagining Hacking". Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, no. 13 (2018). https://doi.org/10.5399/uo/ada.2018.13.1.

Travers, Ann. "Parallel Subaltern Feminist Counterpublics in Cyberspace". Sociological Perspectives 46, no. 2 (June 2003): 223–37. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2003.46.2.223.

Tronto, Joan C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Routledge, 1993.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. "On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales". Common Knowledge 18, no. 3 (1 August 2012): 505–24. https://doi.org/10.1215/0961754X-1630424.

———. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, 2015.