Toward a Minor Tech:AnikinaKeskintepe5000

Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice in Media Arts and Resistant Tech

Introduction

Speculative narratives of (techno)magic such as those offered by feminist technoscience, cyberwitches and techno-shamanism come from knowledge systems long marginalised in a hyper-optimised and hard-science-reliant capitalist discourse. Aiming to de-centre Western rational imaginaries of technology, they speak from decolonial and translocal perspectives, in which the relations between human and technology are reconfigured in terms of care, relationality and multiplicity of epistemic positions. At the same time, such practices and narratives raise interesting questions about the epistemic and aesthetic procedures involved in the relationship of technology and magic. What is even more intriguing is their relationship to the existing critiques of binary definitions of technology, such as Haraway’s ‘naturecultures’. How do these speculative practices enable critical approaches to technology?

In this paper, we consider (techno)magic as relational ethics combined with the capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from commodified forms of belief and knowledge and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine. Situated within the context of resistant tech practices and media art, we will consider some ways in which “magic” in the age of hegemonic Western epistemologies acts as alternative political imaginaries. Drawing on feminist STS and work of artists such as Choy Ka Fai, Omsk Social Club, Ian Cheng, Suzanne Treister and others, we propose to address (techno)magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice.

Situating (Techno)magic

Recent exhibitions demonstrate an interest in technology as connected to, intermixed with or implicated in magical practices. Inke Arns’ “Technoshamanism” (2021) at HMKV Hartware MedienKunstVerein, in Dortmund, Germany, was, perhaps, the most directly relevant to the topic. “Post-Human Narratives—In the Name of Scientific Witchery” (2022) at Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, curated by Kobe Ko, explored para-scientific, esoteric and unorthodox medical practices mixing science and witchcraft. “Wired Magic” (2020) at Haus der Elektronischen Künste Basel, curated by Yulia Fisch and Boris Magrini, focused on the rituals and methods of artists intertwining magical practices with technology. Recently, “The Horror Show!” (2023) at Somerset House, London, contained a section titled “Ghost”, which outlined the British history of post-spiritualist hauntologies of electronic media.

As Jamie Sutcliffe notes at the launch of “Magic”, a collection he edited in the Whitechapel series “Documents of Contemporary Art”, the interest towards magical practices in arts reemerges every few years. [1] However, the specific intersection of the magical and the technological also tends to follow waves of innovation and the consequent waves of anxiety about technology within public discourse (as can be seen even in the recent rise in apocalyptic debates about artificial intelligence after the launch of ChatGPT). They often refer to the famous quote by Arthur C. Clarke: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (Clarke). What does this quote say about these debates? More often than not, it is understood as a necessity for linear progress: if technology is to advance sufficiently, it must undergo the process of development. It also implies that advanced technology cannot avoid being opaque: its internal operation must be inaccessible to the use, casting the human-technology relationship into the categories of “belief” or “trust”.

What is often forgotten in these discussions is the fact that these narratives are produced by the specific tech companies who are fully responsible for making technology opaque or not. The anxiety-driven narratives tend to forego the issues of ethics and care in favour of driving catastrophic imaginaries of technology. Therefore, critical attention to these narratives, while not being the main focus of this article, must be a starting point for any discussion of the imaginaries of technology. And it should be clearly understood that the imaginaries of technology are as crucial for the understanding of its socio-political unfolding and operation as the issues of its functionality, operation and economy. With this in mind, we would like to re-situate our proposition of (techno)magic by taking it outside of the binary of rationality and irrationality. Rather, we would organise it around the following question: what place is accorded to magic in the current discourses of technology, both fueled by and shielded from practices of belief?

If we approach magic and technology as fields of knowledge with specific genealogies, we will often find them entangled. Erkki Huhtamo outlines the archaeology of magic in media, pointing out that the development of media technologies is closely tied to magic, from Mechanical Turk to moving images and animation (Huhtamo). In the West, the Victorian history of spiritualism and mesmerism, ghost photography and technologically aided “neo-occult” séances directly connected supernatural forces, energies and spirits with the newly introduced technological and scientific advancements (see Chéroux et al. 2005, Mays and Matheson 2013). Jeffrey Sconce in “Haunted Media” addresses a particular kind of electronic presence, “at time occult” sense of livenes or “nowness” that inhabits the electronic media (2000). This history extends back to the invention of modern means of communication that introduced simultaneity and immediacy as radically new types of experience of other people’s voices and images, such as with the introduction of telegraph by Samuel Morse in 1844 in the USA, or photography by Louis Daguerre in 1839 in France. [2] These histories (while a close look at them is beyond the scope of our current exploration) bring an interesting dimension to the intersections of magic and technology.

First of all, the contemporary idea of “magic” itself is constituted and situated as a term created by Western modern technologies and Western orientalism, where the inevitable categorisation of unexplained phenomena either as scientific truths or as magical illusions played a significant role in the construction of the myth of contemporary science as rational and infallible. Secondly, while “magic” as a term serves to further underscore the terms “science” and “technoscience” as rational, magic as such simply refers to alternative knowledge systems in which the myth of rationality is not the dominant one, and other cosmologies can come to the fore. Depending on how magic is understood within these two senses (as a Western term for everything irrational or as a word referring to cosmologies outside of it), and what kind of knowledge system stands behind it, we can construct multiple interpretations of magic, including ones where magic is read as modernity’s ultimate technology, and ones where magic is proposed as alternative to technology. In line with the first understanding, Arjun Appadurai speculates that capitalism can be also seen as “the dreamwork of industrial modernity, its magical, spiritual and utopian horizon, in which all that is solid melts into money” (481). He notes:

Capitalism is fundamentally about disciplined dreaming, playful calculation, and speculative productivity. In its visions of growth without limit, of innovation as habit, and of risk as something to be exploited and not only to be hedged against, capitalism is always a dream about future value, a stage for negotiations between the visible and the invisible, a procedure for the disruption of routine, and a set of rules for the always expanding realm of the unruly and the unruled (483).

In this reading, calculation and speculation that predict future values in pursuit of growth and innovation are the mechanisms with which new frontiers are assumed and immediately subjugated under this logic.

The second understanding of magic as alternative to technology can be approached through the work of Federico Campagna, for whom Magic and Technic are two of the many possible “reality-settings” - “implicit metaphysical assumptions that define the architecture of our reality, and that structure our contemporary existential experience” (4). While he does not exclude the existence of other knowledge systems beyond these two, he sees Magic as oppositional to Technic: if Technic’s first-order principle is the knowability of all things through language, Magic’s first and original principle is that of the “ineffable”, where “the ineffable dimension of existence is that which cannot be captured by descriptive language, and which escapes all attempts to put it to ‘work’ - either in the economic series of production, or in those of citizenship, technology, science, social roles and so on” (10). This is an important distinction in the quantified world of digital culture: “being put to work” means not only the physical labour process, but also various data being put to work within a statistical model, or being valorised in any other way.

What we are interested in, in relation to (techno)magic is looking at it as epistemic acts or acts of knowledge construction in art (specifically media art) and resistant tech practices in order to see what alternative ideas of technology we could trace through them. We are also interested in seeing the potential impact of such reframing for the ethics and epistemics of human-technology interaction and for developing relations of care with and via technology with others and the world. We approach this from the perspective of our encounters with the concepts of magic in Western art and technology scene, and from our positions as Western-educated curator-researcher and artist-researcher.

It is also important to underline that the kind of “magic” that we mean comes from the inspiration with contemporary artistic research where the magical is interpreted politically: borrowing further from the discussion of “Documents of Contemporary Art”, we are not interested in “esoteric transcendentalism or results-based magic” but rather in “the aspect of ritual that allows for an encounter with otherness in the self”, or “wonderment” (Whitechapel Gallery). Magic, and especially magical rituals, serves as a de-habituation from the naturalised behaviours of epistemic systems we find ourselves in.

What we call (techno)magic, then, is understood, first of all, as an act of granting access to an alternative knowledge system. It retains the techno- part in brackets in order to preserve doubt about the false separation of the types of knowledge represented by the two parts, much in the same way that Appadurai’s speculation removes boundaries between different knowledge practices within capitalist dreaming. We note that Appadurai's speculation that “everything is magical” steps over salient differences that could be contained within the “magical” and its identification with a multiplicity of cultural worlds. And while we take on board Campagna’s designation of “the ineffable” as a way to refuse capitalist capture, we want to further situate it in the context of media art and resistant tech practices, where (techno)magical constructs can act as interventions into knowledge frameworks of late techno-capitalism, extending the relations of care and dissolving the hierarchies of knowledge production inherited from the Western modernity.

The urgency of such care within the entanglements of technology with the world is particularly clear now. As Eduardo Viveiros de Castro argues, Anthropocene-thinking requires reassessing the predominant modes of operation in order to consider the heterogeneity of living and being in the world, accounting for a multiplicity of ontologies. Against the techno-capitalist drive to reduce and enforce hegemonic universal claims and exclude other ways of understanding the world, a framework for reflecting on how the world is for others can be a starting point for making visible and counteracting inequality, ecological destruction and extinction of species. In “Techno-Shamanism” (2021), Inke Arns approached technology and magic intermixing through four focal points: metallurgy and alchemy; cosmology; artificial intelligence and ecology; non-human actors. She underlined ecology as the central idea of the exhibition; for her, the the return to shamanic and animist practices “has to do with the fact that we are living in a time when we realise that the system we have had up to now is also serving to destroy the world as we know it” (Arns). The turn toward alternative knowledge systems also allows to produce alternative conceptions of technology, along with speculations on what kind of world they could engender. The ecological, feminist, decolonial approach is crucial in (techno)magical practice.

What we also want to emphasise against the backdrop of other entanglements of technology and magic, is that the question lies not only in the opposition of magic to technoscience within rationality-irrationality binary, but also in what potential is there for the magical to reinscribe the discredited meanings of the notion of belief. The magical, in the sense that we propose to consider here, activates a different modality of the word “belief” than the commodified belief systems within capitalism. Rather, belief stands for a long-denied possibility of an alternative political imaginary (one that, as Mark Fisher suggests, is excluded within capitalist realism (Fisher)). Within capitalism, belief can only be exercised without judgement within the confines of certain institutions, such as a temple, a church, a hospital, a rave, an art space. In the same way that it discredits other belief systems, the neoliberal mind does not allow “magic” into realms of serious consideration, inflecting it with categorical epistemic downgrade, especially when it comes to research.[3] It is also not by mistake that the most popular magical story of the last thirty years is, essentially, a bureaucratised and regulated environment of a school for wizards. Therefore, in our thinking, this is the core provocation of magic: it activates the systems of belief in a space where they are not supposed to be activated. And non-religious belief seems like a precondition for convivialist politics of coexistence, joyful labour, care and non-hierarchical relationality.

At the same time, we are not suggesting that magic is a universal solution to capitalism; it's not possible to exit into magic as some kind of a primordial innocent state, and no knowledge system can play a role of a “noble savage” at this point in history. To us, magic is a granular, messy middle situated between sliding and not always matching scales of epistemic conditions and politics. This is important in the processes of construction of belief in relation to the scale of technology, which operates differently at the levels of “minor tech” (Andersen, Cox) and at the scaled-up, infrastructural level of corporations and states.

These considerations situate our definition: we understand (techno)magic as an act of transgressing a knowledge system plus relational ethics plus capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. Technology, in relation to magic, should be liberated from being a despirited tool (a hammer), or from being a magic-wand type solution to the world’s problems; (techno)magic activates a possibility of the ineffable, and therefore, uncapturable of magic in certain space-times inside techno-capitalist infrastructures. With this, (techno)magic offers two immediate propositions, in that it 1) accepts “naturecultures” instead of a binary divide between technology and nature; and 2) inserts new granular relationalities between existing extremes, creating “minor” rather than grand narratives.

In the first proposition, (techno)magic blurs the lines between what is considered “natural” and “technological” precisely because it exists at the borders of understanding particular operations as matters of truth, knowledge, (ir)rationality, belief, care or affect. Donna Haraway argues that nature and culture are not separate entities, but rather entangled and co-constructed (Haraway). She states that the distinction between nature and culture is not neutral, but politically and culturally specific, shaped by power dynamics and historical processes. (Techno)magic does not only exist within natureculture, constituting new forms of ritual making and relationality, but is also similarly pre-shaped, as a term, by a particular idea of what is considered “magical” and “technological”, and their place within natureculture. (Techno)magic could be called “ethico-onto-epistemological”, following Karen Barad’s suggestion of the inseparability of ethics, ontology and epistemology (Barad, 90), precisely because it exists at the intersection of politics that argues against separation of these philosophical entities, and because it lends itself to problematising the experiences of the self and being-in-the-world.

Returning to the second proposition, in which (techno)magic complicates the relations of scale by inserting granular relationalities, it is important to underline, again, that (techno)magic does not simply become a technological prosthesis, but also does not become completely externalised as a miracle. Rather, its minor narratives are about acts of personal becoming political through interaction. The relationality of “becoming-familiar” with the machine can be read as a literal familiarising yourself with a machine or technology that is unknown, and experiencing joyful co-production once the machine becomes known to the body and to its epistemic operation. But it can also be read as becoming-closer, like a familiar of a witch, meaning a useful spirit or demon (in European folklore) with whom a contract is made to collaborate. What is important here is the context of opening up new capacities to act, or capacities to act differently in a reality that was previously hidden.

Having proposed to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice, we would like to offer a methodological speculation on what kind of practices could be considered within the remit of (techno)magic, following these two propositions. One example is a ritual-based work by artist Choy Ka Fai. Rituals are important relational practices since they weave together physical bodies through a set of symbolic actions that allow participants to build relationships between each other, with technologies, as well as other entities with the aim of bringing forth a transformational process for the self.

Choy Ka Fai’s audio-visual performance Tragic Spirits (2020) from his project Cosmic Wanderer (2019-ongoing) investigates how shamanic rituals in Siberia in their histories and present constitutions intersect with broader environmental, technological and political shifts. The performance combines audiovisual sequences (which include documentary footage of the artist's journey and 3D visualisations) with a performance by a dancer. While the human dancer performs on stage, her movements are mirrored by a virtual avatar on the screen, transmitted by motion capture. The work suggests the interconnectedness between human body, nature, ritual and technology, culminating in the phrase “I have arrived at the centre of the universe - the universe inside you [me]” (Choy Ka Fai) that appears on the screen during documentary sequences. What Choy Ka Fai suggests is reaching a place and a state of deep connectedness attained through oscillation created by the many components of the ritual. The audio-visual experience, employing music and intense visuals, reaches the point where the energy of sound vibration is felt as a bodily encounter with the magical reality of the 3D figure on the screen.

Speaking of (techno)magic in the case of Choy Ka Fay’s work offers an opportunity to consider what kind of relationality the technological aspects of the work enable in relation to the spiritual ones. While the technology of motion capture in itself focuses on quantifying and abstracting the lived experience, and often serves the monetisation and further capture of data’s value, in Tragic Spirits it seems to be employed towards another goal, namely, mediating the experience of facing the ineffable. The movement between the documentary film, the dancer, the music and the avatar creates a closed circuit loop between the bio-techno-kinetics and their representation on the screen. In doing so, the performance weaves the “blackbox” of technology within a sacred ritual. The motion capture animates the avatar on the screen, allowing the viewers to see the connection between it and the dancer. Yet, considering this bond and the dancer in the traditional sense of shaman entering an altered state of consciousness, the viewers don’t make the same journey as her - the motion capture can mediate and make visible, but can not abstract or datafy the spiritual journey. This is, precisely, one of the major points of the work: the unknowable must be confronted, seen, heard and experienced without being subsumed.

The potential for human-technology relationality that extends beyond the instrumental and the techno-solutionist, of course, doesn’t have to be restricted to media art or research contexts. It can be traced to a variety of lived experiences of technology, from mundane to techno-spiritual. However, it is in artistic practices that we find useful fissures and tensions, and where politics have the potential to become most immediately visible and negotiated.

Care, Feminist Technoscience and (Techno)magic as Relational Ethics

Having established (techno)magic as human-technological relationality, it becomes necessary to further situate it in relation to the ethics and politics of being human: by whom and for whom should this relationality be redefined? Magic has also served as a one of the “categorical fictions that would justify both the non-Western and Euro-American proletarian superstitions by colonial and governmental expansion” (Whitechapel Gallery). Seen as an instrument of imperialism and colonial violence, magic designated what kind of worlds and knowledge systems can exist and, by extension, what kind of environments can be destroyed and what kind of voices will be excluded and dominated. Feminist and decolonial (techno)magic, then, needs to engage with the concepts of positionality, care, labour, embodied experience of life, and demonstrate a particular type of embedded-ness that entails awareness for relationality and multiple ontologies. How could we imagine a feminist approach to (techno)magic that would be well-positioned against the processes of epistemic violence? And what do we mean by care and relational ethics in the context of resistant tech practices and media arts?

The recent work of writer and technologist K Allado-McDowell, whose book Air Age Blueprint weaves theory, poetry, AI-generated text and diagrams in what can be read as a manifesto of cybernetic animism and interspecies collaboration. Allado-McDowell constructs a blueprint of a world where AI allows a wider sense of communication and understanding of non-humans, and where human consciousness is augmented entheogenically,[4] meeting this new universe half-way. While the concept of (techno)magic finds parallels with this imaginative work, as it does with the concept of procedural animism (Anikina), it also finds some differences in the treatment of the role of the human. Reading it both as inspiration and with productive critique, we first trace the question of the possibility of decolonial embedded-ness of non-Western cultural traditions in the Western context; and then consider how to position (techno)magic closer to the applied practices of care, relationality and labour.

Air Age Blueprint underlines the importance of belief systems in the current techno-cultural moment:

The age of the human is defined by our quantifiable effects on natural systems… These effects are in inheritance, the expression of a genetic trauma in the belief systems and sociotechnical structures of the modern West, a kind of curse. Redesigning infrastructure away from Anthropocenic destruction is one way of breaking this curse. But to do this we need a new set of beliefs and a new imaginary (67).

For Allado-McDowell, the new imaginary is built on the premise of “interspecies intelligence” (70), achieved through a combination of entheogenically altered perception and AI sensing systems that would make natural world not only legible to humans, but also deeply understood and acknowledged: “the goal is to articulate an Earth-centric myth that meets the requirements of human flourishing in an ecosystem where humans are recognised as animals dependent on birdsong or jaguar vitality for their survival and thriving” (70).

Allado-McDowell underlines that they conceive of “non-speciest thinking of Indigenous cosmologies and shamanic spirituality as a diverse set of ecological epistemologies: different ways of knowing not just through reason or intuition, but also on the level of ontology and practice” (71). This upholds the initial question: how do we conceive of the lifeworlds of others as “ecological epistemologies” without assimilating them into the language and operation of the late liberalism and Western epistemology - one could argue, often in the same way that the words “shaman” and “shamanic” already do?

Allado-McDowell offers precise critiques of that possibility. They are acutely aware that the proposition for the combination of ecological awareness, technology and entheogenic culture can be (and already is to some extent) subject to capitalist capture and extraction. This is true as much for technology (wearables, augmented reality, global connectedness) and shamanic practices (alienated from their original context and reframed as mindfulness or self-care), as it is for entheogenic practices that are being subsumed and redeveloped as novel psychedelic compounds. To decolonise entheogenesis, Allado-McDowell underlines, the crucial steps are required: “more interrogation of the Anthropocene, associated environmental reversals and technoscientific instrumentalism”, combined with urgent critique of capitalism (77).

Air Age Blueprint seems to come from a particular context of capitalism that puts emphasis on entheogenesis, the universalised image of “ecosemiotics” and references to transhumanism and cybernetics. The narrative proposes outlets for emancipation, yet they seem to circulate within the boundaries of the individual rather than collective practice (in human terms). At the end of the book, the main character, a film-maker and poet, freelances as a beta-tester of a new AI program, Shaman.AI. The character is prompted to “contaminate” the database with indigenous knowledge structures they encountered early in the narrative in the Amazonian rainforest while being taught by a healer. The metaphor of contamination, while already existing in real life interactions with machine learning systems as “prompt injection” (or “injection attack”, in cybersecurity language) is, at the same time, a proposal for subversive action and an acknowledgement of the near-impossibility of direct resistance.

In relation to this view, (techno)magic leaves open the question of interweaving specific cultural practices into its understanding of “magic”. At the moment, (techno)magic, while taking the considerations we outlined above on board, leaves open the question of interweaving a specific cultural practice of magic. This is an unresolved tension that we reserve as a potential task for the future research. In a way, this article is meant to create a space for inviting magic into the broadly defined discussions of media and technology on ethical and political terms; it serves as an academic incantation of a sort, a protective circle for future narratives of (techno)magic to appear and propagate. It focuses on ethics of relationality as understood by feminist technoscience and as ethics that operationalise the terms of labour, embodied experience and care.

Where Allado-McDowell suggests that a future ecosemiotic AI translating between the human and non-human worlds is construed as “what in the Amerindian view might look like a shaman” (71), bringing the Amerindian epistemology into the Western one, we would like to continue the line of questioning into the specific Western politics of imagination, care and labour without choosing a specific magical tradition. First, we are wary of positioning these systems of knowledge as ready-made solutions: indigenous knowledge is not an instrument of care for the Western world. Rebuilding relations of care requires attention to the material and embodied worlds within existing epistemologies. see decolonial epistemologies. Secondly, in the context of existing media art and resistant tech practices, the ideas of “magic” come from very different lifeworlds. Some are employing specific vocabularies to describe technology, such as “spells” or “codebooks”, while not necessarily practicing magic as traditionally understood ( some members of varia and syster server collectives). Some directly draw on the existing witchcraft practices (Cy X, a “Multimedia Cyber Witch”, or Lucile Olympe Haute, artist and author of “Cyberwitches Manifesto”). The International Festival of Technoshamanism in Brazil unites practitioners who integrate computation, software and hardware into existing systems of belief by techno-mediating rituals and approaching technological artefacts as magical tools, beings or effigies. Following this, if there is a specific tradition of magic to draw upon, there is also a multiplicity of potential (techno)magics, each requiring an exploration of the situated knowledge systems and ethical positions of people who adopt them. What becomes important in the context of the current article is considering how these multiple position plug into the existing Western epistemics, and how the disruption of the dominant knowledge systems takes place.

Furthermore, when we refute the idea of “innocence” contained in non-Western lifeworlds (and, therefore, their magical traditions), we encounter the acts of belief in the current Western world in their granular and messy context. What we call technology does not preclude non-instrumental relations to the world, and is sometimes directly contingent on un-articulated acts of belief. For example, this happens in the places where belief is justified by one or another accepted reason, be it a case of cryptocurrency exchange or a shintoist robot priest. In the former, it is a pre-approved belief in the fluctuations of value that upholds the existence of crypto-market; and in the latter, it is the established religious practice that paves the way for technology to be accepted. Similarly, acts of belief are encountered where care is monetised, such as in toys Ai-Bo or Tamagochi, or in a medical field (where care is a valuable resource that can be outsourced to robots). If we let go of these commodified types of belief, what prevents us from making new relations of care outside of the boundaries drawn by techno-capitalism? Lucille Olympe Haute in Cyberwitches Manifesto, for instance, foregrounds magic as a practice of resistance grounded in feminist ethics. She writes about technology and magic without hierarchical distinction:

Let's use social networks to gather in spiritual and political rituals. Let's use smartphones and tarot cards to connect to spirits. Let's manufacture DIY devices to listen to invisible worlds (n.p.).

In the ethos of this manifesto, technology is liberated from the burden of being rational and therefore is reinscribed back into the realm of ethico-political practice. What other practices can we think of that would allow us to inscribe relationality of care into the current technological landscape?

We imagine (techno)magic as a materially embedded and embodied feminist practice that starts from a point in which non-humans, including machines, are not outside of the normative human-to-human relationality. This calls also for the rethinking of the commons and for the new ethics of relationality with non-humans. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa explores this in her book Matters of Care. She calls for a deeper integration of the concept of care into the relational and material consideration of the world:

Care is everything that is done (rather than everything that ‘we’ do) to maintain, continue, and re-pair ‘the world’ so that all (rather than ‘we’) can live in it as well as possible. That world includes… all that we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web (modified from Tronto 1993, 103) (161).

She follows Bruno Latour in underlining that human existence is not dependent and deeply interwoven solely with humans, but rather on many others, including technological things. Latour calls for turning away from “matters of fact” and to “matters of concern” as a resolution of the issue of taking “facts” for granted and therefore voiding the relations with these matters of political urgency. Puig de la Bellacasa then suggests a productive critique of escalating “matters of concern” further as “matters of care,” ”in a life world (bios) where technosciences and naturecultures are inseparably entangled, their overall sustainability and inherent qualities being largely dependent upon the extent and doings of care” (Brons, n.p.).

Turning towards specific entanglements produced by artists, we can consider another ritualistic artwork that reframes technology in relation to belief systems. Omsk Social Club’s uses LARPing (Live Action Role Play) as a way to create “states that could potentially be fiction or a yet unlived reality” (Omsk Social Club). In each work, a future scenario functions “as a form of post-political entertainment, in an attempt to shadow-play politics until the game ruptures the surface we now know as life” (Omsk Social Club). Some of the themes they explore include rave culture, survivalism, desire and positive trolling. The work S.M.I2.L.E. bears particular interest as a “mystic grassroot” ceremony (Omsk Social Club) that explores freedom from protocols of quantification and efficiency in the age of technological precision. The work starts with each user giving up one of their 5 core senses to engage in synesthetic experiences and reach other states of sensing. The work is, at the same time, a critique of the communities that gather around eco-technological innovation, and a spiritual ceremonial practice through which users are exploring synesthetic acts including being blindfolded, fasting and dancing. These allow users to engage with the LARP structure as a ritual that critiques neopagan constructions for their lack of reflexivity, and suggests a local politics of being, interacting, sensing and playing.

It is important to note that the word “users” is chosen by Omsk Social Club to underline the role of the ceremony as a quasi-technology or software for the participants to make use of: the work reactivates machine-human relations as politically engaged and embodied ritual experiences. Omsk Social Club often works outside or between frameworks set by art institutions, engaging with spaces such as raves or the office space of a museum - institutional infrastructures outside of the “white cube”. In doing so, they also reinscribe the format of LARP in the context of art and technology infrastructures, producing critical meaning through the embodied interaction of the players/users. As Chloe Germaine notes, LARP is distinct from other modes of playing in how it prioritises the embodied immersion and “inhabiting both position of ‘I’ and ‘They’ as player-character negotiations” (Germaine 3). Furthermore, Germaine underlines how the “magic circle”, or limits of what is considered an in-game place and what is “out of character area”, allows the players to “hack and transform identities and social relationships” (Germaine 3). In Omsk Social Club’s, “creating a drift between body and mind” (Anikina, Keskintepe) is an important part of the ritualised engagement. LARPing is a kind of an “open source magic” and a “theatre for the unconscious” in that it allows the users to get an embodied experience of technology (including the technology of their own body) and practice and experience new political positions (Anikina, Keskintepe).

Choosing to care actively is the starting point of considering (techno)magic as a relational ethics and embodied epistemic practice. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from libertarian, commodified, power-hungry, toxic, conquering forms of belief and knowledge, and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine.

By Way of Conclusion: Spirit Tactics and Aesthetics for Anthropocene

Part of becoming-familiar means letting go of human exceptionalism to an extent: becoming on the scale that, in current theoretical thinking, extends to being posthuman or even ahuman (as Patricia McCormack suggests). While MacCormack’s writing is oriented within the animal rights discourse, suggesting “ahumanism” as part of abolitionist stance, we share in the call towards the epistemic experimentation that this position entails and in her proposition of “occulture” as a kind of playful epistemics. The methodologies of (techno)magic extend beyond rituals: we should also be able to imagine other resistant forms of looking toward other knowledge systems and lifeworlds. Crucially, this perspective means entangling the technological into what could be called “media-nature-culture”, bringing about a “qualitative shift in methods, collaborative ethics and, (…), relational openness” (Braidotti 155). It suggests a material and embedded form of thinking, which increases the capacity to recognize the diverse and plural form of being. Recognising technological mediation, synthetic biology and digital life leads to emergence of different subjects of inquiry, non-humans as well as humans as knowledge collaborators (Braidotti).

In this light, it is important to address the question of aesthetics and figuration within (techno)magic. Aesthetics here should be seen, primarily, as the realm of the sensible and its distribution (Ranciére), most urgently in relation to the suffering brought by the climate emergency, experienced unevenly across the planet. And while (techno)magic does often involve particular surface-level aesthetics, and artists working with such contexts often utilise “alien” logos and fonts (OMSK Social Club), diagrams (Suzanne Treister) or sigil-like imagery (Joey Holder), the question of sensing goes beyond symbolic relations. Rather, it becomes interesting to approach the media landscape in terms of the Patchy Anthropocene: an idea formulated to disentangle from the universalising and flattening terms of Anthropocene, such as “planetary” (Tsing, Mathews, Bubandt). The idea of a “patch”, they explain, is borrowed from landscape ecology that understands all landscapes as necessarily entangled within broader matrices of human and nonhuman ecologies.

Speculatively, and trying not to create any more new terms, we might want to designate a kind of spirit tactics for image politics in the Anthropocene discourse, as it requires engagement with images as apparitions of capitalism: acknowledging symbolic power and complications of representation, yet focusing on data structures, on the operational images and infrastructural politics of collective thinking and action. Here, perhaps, a note on the two distinct interpretations of the word "spirit" is in order: first, understood as “willpower” or inner determination. Secondly, “spirit” can refer to the supernatural forces figured as beings or entities that are therefore able to participate in political life and in rituals that activate systems of belief. In other words, we can consider spirit tactics as a proposition for a form of political determination to be actualised within (techno)magic, be it images, alternative imaginaries, portals, diagrams and operationalised ways of embodied thinking (rituals).

(Techno)magic asks for the emergence of layered tactics of image production that allows both for the processes of figuration and the underlying “invisuality” of what is being figured (e.g. data). One interesting example that speaks about figuration is Ian Cheng’s work Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (2022), an animation produced in a Unity game engine. The work offers a future imaginary of an techno-psycho-spiritual augmentation in a world where “AI entities are permitted to co-inhabit human minds” (Cheng). BOB (“Bag of Beliefs”), as the AI-system is called, is integrated with the human nervous system. BOB is meant to become a “destiny coach”, acting as a simulation, modelling and advising system that guides the human to probabilistically calculated outcomes during their lifetime.

The protagonist of the film is Chalice Wong - a daughter of the scientist responsible for BOB’s development and the first test subject, augmented with BOB since her birth. BOB and Chalice are bound by a contract that allows BOB to take control of life versions of Chalice in order to lead her down to the best possible life path. Yet as film progresses, Chalice is depicted as increasingly alienated and discontent as BOB’s quest for the ideal path of self-actualisation takes over her destiny. She gradually becomes a prosthesis for the AI system. Chalice’s father considers “parenting as programming”, but he also treats his daughter’s fate as an experiment to develop BOB into a commercial product. Animation style, colourful, chaotic and glitchy, which is typical for Ian Cheng’s work, does well to represent both the endless variations of the future that BOB calculates in order to secure the best possible one and the hallucinatory moments of Chalice’s consciousness jumping between her own self and BOB, entangling and disentangling with and from her technological double.

How do we figure our futures from the inside of the capitalist condition in Anthropocene? Life After BOB: The Chalice Study can be seen as a dark speculation on the instrumentalisation of the human “connectedness” to the world, a gamified version where human’s worth is measured on the scale stretching from the failure to the success to self-actualise. The spiritual aspects of Chalice’s journey are shown as completely commercialised: fate, destiny, willpower are all presented as part of a cognitive product that sees the human body as the latest entity to capitalise on.

One particular aspect of Life After BOB: The Chalice Study is significant for questioning the tactics of visualisation. As the work is completed in the game engine, a lot of the underlying data structure for the animation is not hand-coded, but is operationalised through various shortcuts that are usually used in game design. These include light, movement, glitchy interactions of various objects. Ian Cheng notes that making animation in a game engine is more like creating software, allowing for a fast production of iterations of the scenes (Nahari). Furthermore, the prequel to this work, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018-2019), was a live simulation of BOB displayed in a gallery as an artificial life entity that could be interacted with. These procedural aspects of visualisation introduce a consideration of underlying processes: even though Life After BOB: The Chalice Study is a recorded animation and not a live simulation like Ian Cheng’s previous works (the Emissary trilogy), the feel of images being driven by computational processes rather than manual aesthetic choices is still retained. In this sense, and also in the narrative choices of a human child augmented by an AI spirit, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study presents interesting considerations for the visuality of (techno)magic as a kind of combinatorial aesthetic figuration that unfolds between the figuration and its underlying infrastructure.

Ultimately, however, it is not the figuration or even the visualisation of the underlying data structures that become the priority for (techno)magical aesthetics. What is more interesting to us is the epistemic operation and the ways to spatialise and bend cognitive habits. One tentative method that we suggest for this as co-authors of this paper and as a collective is a diagrammatic thinking. A diagram, as we see it, can be critical, operative and performative. It can actualise connections and lines of action. A diagram does not represent, but maps out possibilities; a diagram is a display of relations as pure functions. More importantly, a diagram can enable various scaling of possibilities: from individual tactics to mapping out collective action and to infrastructural operation. K Allado-McDowell employs diagrams in Air Age Blueprint. They comment: the task at hand “is not just ecological science but ecology in thought: how do we construct an image of nature with thought - not through representation or translation, but somehow held in the mind in its own right?” (73). Another example of diagrammatic thinking is the work of Suzanne Suzanne Treister, Technoshamanic Systems (2020–21). Technoshamanic Systems (2020–21) “presents technovisionary non-colonialist plans towards a techno-spiritual imaginary of alternative visions of survival on earth and inhabitation of the cosmos … [and] encourages an ethical unification of art, spirituality, science and technology through hypnotic visions of our potential communal futures on earth” (Treister). The diagrammatic nodes of Treister’s work underline various forgotten and “discredited” lines of knowledge, putting together alternative structures that extend both into the genealogy of knowledge and into the potential versions of the contemporary and of the future. In doing so, it achieves a kind of an epistemic restoration through implying that these nodes belong to the same planes, categories, surfaces and levels of consideration - a move opposite to epistemic violence and hegemonic narratives.

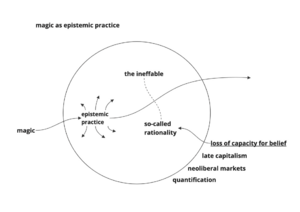

Figure 1 is a diagram drawn by us that represents the role of magic as an epistemic practice in relation to the embodied interaction of individuals (primarily Western subjects) through the world of late techno-capitalism. They can engage with magic (or (techno)magical rituals) as a relational and embodied epistemic practice; yet what they also face, within the Western epistemics, is an overall loss of capacity for belief, fueled by neoliberal markets and datafication. In this epistemic journey, they have to negotiate the pressure of so-called rationality and the inevitable presence of the ineffable, which can be also very normatively interpreted and captured in the form of popular entertainment, traditional belief systems and even random, sub-individual algorithmicised affects of image flows and audiovisual platforms such as TikTok.

Within the (techno)magical consideration, many various diagrams are possible. The aim behind them is not to stabilise, but to make visible and to multiply alternatives. However, this is just one of many potential “spirit tactics”: our ultimate proposition is to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice. We appeal to a tentative future: thought becoming operationalised as we engage in thinking-with diagrams and use diagrams as rituals-demarcated-in-space; finding solidarity with our dead - ancestors, but also crude oil - in the face of the Anthropocene; rituals against forgetting; making technospirits and conjuring worlds.

Endnotes

- ↑ And similar paragraphs referring to recent exhibitions can be found in the earlier collections of academic writing; see, for example, “The Machine and the Ghost” (2013).

- ↑ Here, the public presentation is important for the context, so the invention of photograms by Fox Talbot in Britain in 1834 can be omitted.

- ↑ It is not by chance that when this paper was proposed, in the process of development, to the NECS 2023 conference dedicated to the topic of “Care”, it was allocated in the panel “Media, Technology and the Supernatural”.

- ↑ Entheogen means a psychoactive, hallucinogenic substance or preparation, especially when derived from plants or fungi and used in religious, spiritual, or ritualistic contexts.

Works cited

Allado-McDowell, K. Air Age Blueprint. Ignota Books, 2023.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Geoff Cox. ‘Toward a Minor Tech’. A Peer-Reviewed Newspaper, edited by Christian Andersen and Geoff Cox, vol. 12, no. 1, Apr. 2023, p. 1.

Anikina, Alexandra. ‘Procedural Animism: The Trouble of Imagining a (Socialist) AI’. A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, vol. 11, no. 1, Oct. 2022, pp. 134–51.

Anikina, Alexandra, and Yasemin Keskintepe. Personal conversation with Omsk Social Club. 2 Feb. 2023.

Appadurai, Arjun. ‘Afterword: The Dreamwork of Capitalism’. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 35, no. 3, 2015, pp. 481–85.

Arns, Inke. ‘Deep Talk Technoschamanismus’. Kaput - Magazin Für Insolvenz & Pop, 5 Dec. 2021, https://kaput-mag.com/catch_en/deep-talk-technoschamanism-i_inke-arns_videoeditorial_how-does-it-happen-that-in-the-most-diverse-places-artists-deal-with-neo-shamanistic-practices/.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, 2007.

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman Knowledge. John Wiley, 2019.

Brons, Richard. ‘Reframing Care – Reading María Puig de La Bellacasa “Matters of Care Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds”’. Ethics of Care, 9 Apr. 2019, https://ethicsofcare.org/reframing-care-reading-maria-puig-de-la-bellacasa-matters-of-care-speculative-ethics-in-more-than-human-worlds/.

Campagna, Federico. Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Cheng, Ian. Life After BOB: The Chalice Study. Film, 2022, https://lifeafterbob.io/.

Chéroux, Clément, et al. The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult. Yale University Press, 2005.

Clarke, Arthur C. Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. Harper & Row, 1973.

de la Bellacasa, María Puig. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. U of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009.

Germaine, Chloe. ‘The Magic Circle as Occult Technology’. Analog Game Studies, vol. 9, no. 4, 2022, https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/631195/3/The%20Magic%20Circle%20as%20Occult%20Technology%20Draft%203%203-10-22.pdf.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Haute, Lucile Olympe. ‘Cyberwitches Manifesto’. Cyberwitches Manifesto, 2019, https://lucilehaute.fr/cyberwitches-manifesto/2019-FEMeeting.html.

Huhtamo, Erkki. ‘Natural Magic: A Short Cultural History of Moving Images’. The Routledge Companion to Film History, edited by William Guynn, Routledge, 2010.

Ka Fai, Choy. Tragic Spirits. Audio-visual performance, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOTOn0WtaFA&ab_channel=CosmicWander%E7%A5%9E%E6%A8%82%E4%B9%A9.

Latour, Bruno. ‘Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern’. Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, Jan. 2004, pp. 225–48.

MacCormack, Patricia. The Ahuman Manifesto: Activism for the End of the Anthropocene. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Mays, Sas, and Neil Matheson. The Machine and the Ghost: Technology and Spiritualism in Nineteenth- to Twenty-First-Century Art and Culture. Manchester University Press, 2013.

Nahari, Ido. ‘Empathy Is an Open Circuit: An Interview with Ian Cheng’. Spike Art Magazine, 9 Sept. 2022, https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/?q=articles/empathy-open-circuit-interview-ian-cheng.

Olympe Haute, Lucile. ‘Cyberwitches Manifesto’. Cyberwitches Manifesto, 2019, https://lucilehaute.fr/cyberwitches-manifesto/2019-FEMeeting.html.

OMSK Social Club. S.M.I2.L.E. Ceremony, Volksbühne Berlin, 2019, https://www.omsksocial.club/smi2le.html.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Duke University Press, 2000.

Treister, Suzanne. Technoshamanic Systems. Diagrams, 2021-2022, https://www.suzannetreister.net/TechnoShamanicSystems/menu.html.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, et al. ‘Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology: An Introduction to Supplement 20’. Current Anthropology, vol. 60, no. S20, Aug. 2019, pp. S186–97.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. ‘On Models and Examples: Engineers and Bricoleurs in the Anthropocene’. Current Anthropology, vol. 60, no. S20, Aug. 2019, pp. S296–308.

Whitechapel Gallery. ‘Magic: Documents of Contemporary Art’. YouTube, 2021, September 18, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUOYhzZkxwk&ab_channel=WhitechapelGallery.