Toward a Minor Tech:Kir 500

As the reliance on digital platforms expands, so does the relevance and urgency to develop more diverse critical tools that scrutinise their environments, affordances and in-built relations. This begs for research outside the academic institution to establish the ground for critical dialogue and productive speculations. Relatedly, a tendency emerges across the artistic field to spatialise digital platforms, embody them and critically put them on display. How do scale and situatedness appear and matter across such artworks? And (how) do such creative contributions help to critically nuance diverse existing understandings of large-scale digital platforms? Without drawing any conclusions, this text devotes particular attention to the spatial parameters presented through the actions of misplaced content, disrupted archives and dysfunctional systems in three diverse artistic examples that explore different spatial configurations (Berlant 2016; Stanfill 2015).

Scene 1: Online A left-aligned list of words is set in a bold black and almost illegible type. These are the names of the artists. Listed underneath are classical blue-lettered hyperlinks. The page contains nothing more than this: names in bold, accompanied by blue plane links (fig 1).

The digital platform Cosmos Carl presents a website and framework with links to artistic initiatives that appropriate existing commercial platform tools. Amongst the works are projects that modify publicly accessible surveillance cameras (Someplace, somewhere 2020) or intentionally misuses Airbnb to present infrastructures of lakes in Georgia (Petits Filous (26,000 Rivers)). While internet pages are commonly visited with a purpose and directed according to expectations (Bucher 2017), Cosmos Carl playfully challenges such online navigation.

Scene 2: At streetlevel

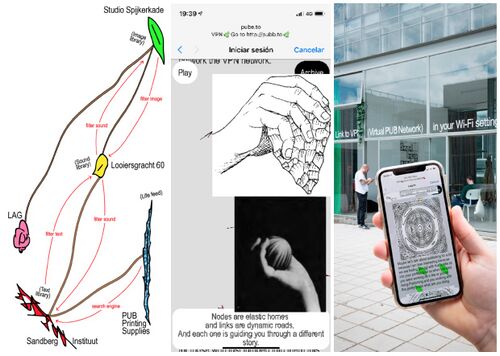

Imagine a locally disrupted online platform: a scattered illustration turns up on a smartphone screen: the circular pattern turns into a globe, then an installation setting, and finally into the shape of a famous cartoon character.

The scene unfolding describes the features of the emancipatory file server, VPN (Virtual PUB Network) (fig. 2). As an artistic work, VPN served the purpose of mapping and archiving the graduation show of the Art and Design university Sandberg Instituut (Amsterdam). However, whereas archives typically help to create order, the visual interfaces of VPN are location-dependent and coded to intentionally disrupt the user's scroll. When introducing VPN, what is of interest is not so much the content but the disrupted archives. VPN presents how an interdisciplinary systematic creative strategy may provoke interaction between artists, audience, and spatial surroundings (Bhowmik & Parikka 2021).

Scene 3: On sea

From a mesh of online strategic misusage to locally intended server disruption, the final scene brings us onto the hyper-local solar panel-powered floating context of the art collective 100 Rabbits.

Living, working, and DIY making minor tech tools from their sailboat at open sea, the setup of 100 Rabbits includes everything from generating the power they need to build the programmes they use (drawing, writing, editing, archiving, coding) (Fig. 3). When at sea, bandwidth is limited, electricity scarce, and access to information is protocol dependent, effectively the tools and programmes by 100 Rabbits demand simple constructions (to be disassembled, reassembled, and repaired) (Latour 1994). With the two former cases in mind, 100 Rabbits presents a hyper-local scale of how consequences of connectivity limitations and power consumption materialise into creative DIY solutions.