Pdf:APRJA Minor Tech

A Peer-Reviewed Journal About

MINOR TECH

Christian Ulrik Andersen

& Geoff Cox (Eds.)

Camille Crichlow

Scaling Up, Scaling Down:

Racialism in the Age of Big Data

Scaling Up, Scaling Down: Racialism in the Age of Big Data

Abstract

This article explores the shifting perceptual scales of racial epistemology and anti-blackness in predictive policing technology. Following Paul Gilroy, I argue that the historical production of racism and anti-blackness has always been deeply entwined with questions of scale and perception. Where racialisation was once bound to the anatomical scale of the body, Thao Than and Scott Wark’s conceptualisation of “racial formations as data formations” inform insights into the ways in which “race”, or its 21st century successor, is increasingly being produced as a cultivation of post-visual, data-driven abstractions. I build upon analysis of this phenomena in the context of predictive policing, where analytically derived “patrol zones” produce virtual barriers that divide civilian from suspect. Beyond a “garbage in, garbage out” critique, I explore the ways in which predictive policing instils racialisation as an epiphenomenon of data-generated proxies. By way of conclusion, I analyse American Artist’s 21-minute video installation 2015 (2019), which depicts the point of view of a police patrol car equipped with a predictive policing device, to parse the scales upon which algorithmic regimes of racial domination are produced and resisted.

Introduction

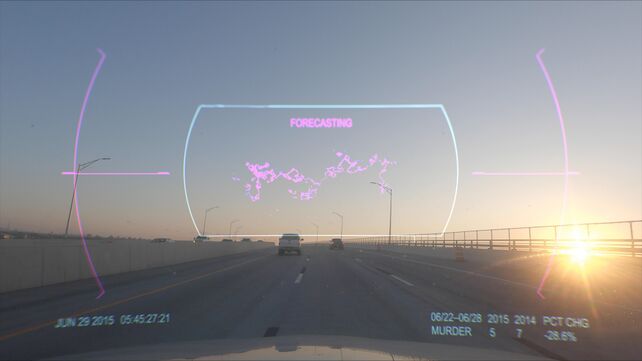

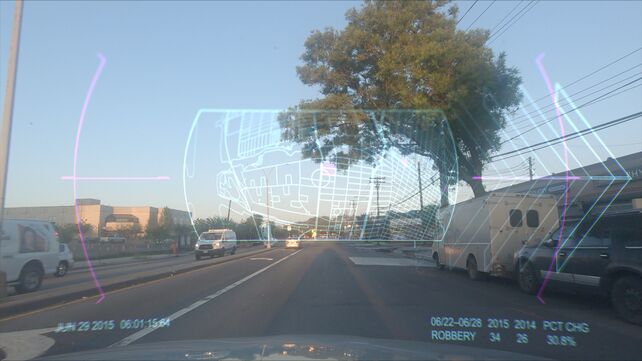

2015, a 21-minute video installation shown at American Artist’s 2019 multimedia solo exhibition My Blue Window at the Queen’s Museum in New York City, assumes the point of view of a dashboard surveillance camera positioned on the hood of a police car cruising through Brooklyn’s side streets and motorways. Superimposed on the vehicle’s front windshield, a continuous flow of statistical data registers the frequency of crime between 2015 and the preceding year: “Murder, 2015: 5, 2014: 7. Percent change: -28.6%”. Below a shifting animation of neon pink clouds, the word “forecasting” appears as the sun rises on the freeway. The vehicle suddenly changes course, veering towards an exit guided by a series of blinking ‘hot spots’ identified on the screen’s navigation grid. Over the deafening din of a police siren, the car races towards its analytically derived patrol zone. The movement of the camera slows to a stop on an abandoned street as the words “Crime Deterred” repetitively pulse across the screen. This narrative arc circuitously structures the filmic point of view of a predictive policing device.

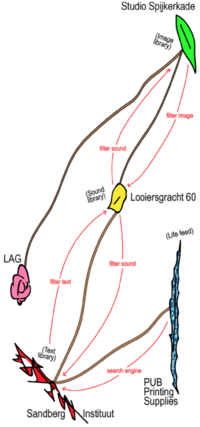

In tandem with American Artist’s broader multimedia oeuvre, 2015 similarly operates at historical intersections of race, technology, and knowledge production. Their legal name change to American Artist in 2013 suggests a purposeful play with ambivalence. One that foregrounds the visibility and erasure of black art practice, asserting blackness as descriptive of an American artist, while simultaneously signalling anonymity to evade the surveillant logics of virtual spaces. Across their multimedia works forms of cultural critique stage the relation between blackness and power while addressing histories of network culture. Foregrounding analytic means through which data-processing and algorithms augment and amplify racial violence against black people in predictive policing technology, American Artist’s 2015 interweaves fictional narrative and coded documentary-like footage to construct a unique experimental means to invite rumination on racialised spaces and bodies and their assigned “truths” in our surveillance culture.

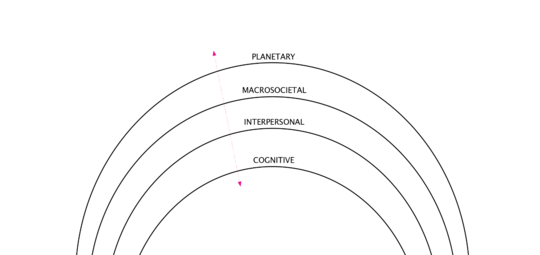

As large-scale automated data processing entrenches racial inequalities through processes indiscernible to the human eye, 2015 plays with scale as response. Following Joshua DiCaglio, I invoke scale here as a mechanism of observation that establishes “a reference point for domains of experience and interaction” (3). Relatedly, scale structures the relationship between the body and its abstract signifiers, between identity and its lived outcomes. As sociologist and cultural studies scholar Paul Gilroy observes, race has always been a technology of scale: a tool to define the minute, miniscule, microscopic signifiers of the human against an imagined nonhuman ‘other’. In the 21st century, however, racialisation finds novel lines of emergence in evolving technological formats less constrained by the perceptual and scalar codes of a former racial era. No doubt, residual patterns of racialisation at the scale of the individual body remain entrenched in everyday experience. Here, however, I adopt a different orientation, one that specifically examines the less considered role of data-driven technologies that increasingly inscribe racialisation as a large-scale function of datafication.

Predictive policing technology relies on the accumulation of data to construct zones of suspicion through which racialised bodies are disproportionately rendered hyper-visible and subject to violence (Brayne; Chun). Indeed, predictive analytics range across a wide spectrum of sociality. Health care algorithms employed to predict and rank patient care, favour white patients over black (Obermeyer) and automated welfare eligibility calculations keep the racialised poor from accessing state-funded resources, for example. (Rao; Toos). Relatedly, credit-market algorithms widen already heightened racial inequalities in home ownership (Bhutta et. al). While racial categories are not explicitly coded within the classificatory techniques of analytic technologies, large-scale automated data processing often produce racialising outputs that, at first glance, appear neutral.

Informed by the “creeping” role of prediction and subsequent “zones of suspicion,” I consider how racial epistemology is actively reconstructed and reified within the scalar magnitude of “big data”. This article will focus on racialisation as it is bound up in the historical production of blackness in the American context, though I will touch on the ways in which big data is reframing the categories upon which former racial classifications rest more broadly. Following Paul Gilroy’s historical periodisation of racism as a scalar project of the body that moves simultaneously inwards and downwards towards molecular scales of corporeal visibility, I ask how “big data” now exerts upwards and outwards pressures into a globalised regime of datafication, particularly in the context of predictive policing technology. Drawing from Thao Than and Scott Wark’s conception of racial formations as data formation, that is, “modes of classification that operate through proxies and abstractions and that figure racialized bodies not as single, coherent subjects, but as shifting clusters of data” (1), I explore the stakes and possibilities for dismantling racialism when the body is no longer its singular referent. To do this, I build upon analysis of this phenomena in the context of predictive policing, where analytically derived “patrol zones” produce virtual barriers that that map new categories of human difference through statistical inferences of risk. I conclude by returning to analysis of American Artist’s 2015 as an example of emergent artistic intervention that reframes the scales upon which algorithmic regimes of domination are being produced and resisted.

The scales of Euclidean anatomy

The story of racism, as Paul Gilroy tells it, moves simultaneously inwards and downwards into the contours of the human body. The onset of modernity – defined by early colonial contact with indigenous peoples and the expansion of European empires, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and the emergence of enlightenment thought – saw the evolution of a thread of natural scientific thinking centered around taxonomical hierarchies of human anatomy. 18th century naturalist Carl Linnaeus’s major classificatory work, Systema Naturae (1735), is widely recognised as the most influential taxonomic method that shaped and informed racist differentiations well into the nineteenth century and beyond. Linnaeus’s framework did not yet mark a turn towards biological hierarchisation of racial types. Nevertheless, it inaugurated a new epoch of race science that would collapse and order human variation into several fixed and rigid phenotypic prototypes. By the onset of the 19th century, the racialised body took on new meaning as the terminology of race slid from a polysemous semantic to a narrower signification of hereditary, biological determinism. In this shift from natural history to the biological sciences, Gilroy notes a change in the “modes and meanings of the visual and the visible”, and thus, the emergence of a new kind of racial scale; what he terms the scale of comparative or Euclidean anatomy (844). This shift in scalar perceptuality is defined by “distinctive ways of looking, enumerating, measuring, dissecting, and evaluating – a trend that could only move further inwards and downwards under the surface of the skin (844). By the middle of the 19th century, for example, the science of physiognomy, phrenology and comparative anatomy had encoded racial hierarchies within the physiological semiotics of skulls, limbs, and bones. By the early 20th century, the eugenics movement pushed the science of racial discourse to ever smaller scopic regimes. Even the microscopic secrets of blood became subject to racial scrutiny through the language of genetics and heredity.

Now twenty years into the 21st century, our perceptual regime has been fundamentally altered by exponential advancements in digital technology. Developments across computational, biological, and analytic sciences produce new forms of perceptual scale, and with it, as Gilroy suggests, open consideration for envisioning the end of race as we know it. Writing in the late 1990’s, Gilroy observed how technical advancements in imaging technologies, such as the nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscope [NMR/MRI], and positron emission tomography [PET], “have remade the relationship between the seeable and the unseen” (846).” By imaging the body in new ways, Gilroy proposes, emergent technologies that allow the body to be viewed on increasingly minute scales “impact upon the ways that embodied humanity is imagined and upon the status of bio-racial differences that vanish at these levels of resolution” (846). This scalar movement ever inwards and downwards became especially evident in the advancements of molecular biology. Between 1990 and 2003, the Human Genome Project mapped the first human genome using new gene sequencing technology. Their study concluded that there is no scientific evidence that supports the idea that racial difference is encoded in our genetic material. Once and for all, or so we thought, biological conceptions of race were disproved as a scientifically valid construct. In this scalar movement beyond Euclidean anatomy, as Gilroy discerns, the body ceases to delimit “the scale upon which assessments of the unity and variation of the species are to be made” (845). In other words, we have departed from the perceptual regime that once overdetermined who could be deemed ‘human’ at the scale of the body.

Rehearsing this argument is not meant to suggest that racism has been eclipsed by innovations in technology, or that racial classifications do not remain persistently visible. Gilroy (“Race and Racism in ‘The Age of Obama’”), along with his critics, make clear that the “normative potency” of biological racism retains rhetorical and semiotic force within contemporary culture. Efforts to resuscitate research into race’s biological basis continue to appear in scientific fields (Saini), while the ongoing deaths of black people at the hands of police, or the increase in violent assaults against East Asian people during the Corona virus pandemic, demonstrate how racism is obstinately fixed within our visual regime. Gilroy suggests, however, that while the perceptual scales of race difference remain entrenched, these expressions of racialism are inherently insecure and can be made to yield, politically and culturally, to alternative visions of non-racialism. To combat the emergent racism of the present, this vision suggests, we must look beyond the perceptual-anatomical scales of race difference that defined the modern episteme. Having “let the old visual signifiers of race go”, Gilroy directs attention to tasks of doing “a better job of countering the racisms, the injustices, that they brought into being if we make a more consistent effort to de-nature and de-ontologize ‘race’ and thereby to disaggregate raciologies” (839).

Attending to these tasks of intervention requires that we keep in mind the myriad ways in which the residual traces left by older racial regimes subtly insinuate the functions of newly emergent “post-visual” technologies. As Alexandra Hall and Louise Amoore observe, the nineteenth century ambition to dissect the body, and thus lay bare its hidden truths, also “reveal a set of violences, tensions, and racial categorizations which may be reconfigured within new technological interventions and epistemological frameworks” (451). Referencing contemporary virtual imaging devices which scan and render the body visible in the theatre of airport security, Hall and Amoore suggest that new ways of visualizing, securitizing, and mapping the body draw upon the old-age racial fantasy of rendering identity fully transparent and knowable through corporeal dissection. While the anatomical scales of racial discourse have not been wholly untethered from the body, the ways in which race, or its 21st century successor is being rendered in new perceptual formats, remains an urgent question.

‘Racial formations as data formations’

Beyond anatomical scales of race discourse, there is a sense that race is being remade not within extant contours of the body’s visibility, but outside corporeal recognition altogether. If the inward direction towards the hidden racial truths of the human body defined the logics and aesthetics of our former racial regime, how might we think about the 21st century avalanche of data and analytic technologies that increasingly determine life chances in an interconnected, yet deeply inequitable world? Can it be said that our current racial regime has reversed racialism’s inward march, now exerting upwards and outwards pressures into a globalised regime of “big data”?

Big data, broadly understood, refers to data that is large in volume, high in velocity, and is provided in a variety of formats from which patterns can be identified and extracted (Laney). “Big”, of course, evokes a sense of scalar magnitude. For data scholar Wolfgang Pietsch, “a data set is ‘big’ if it is large enough to allow for reliable predictions based on inductive methods in a domain comprising complex phenomena”. Thus, data can be considered ‘big’ in so far as it can generate predictive insights that inform knowledge and decision-making. Growing ever more prevalent across major industries such as medical practice (Rothstein), warfare (Berman), criminal justice (Završnik) and politics (Macnish and Galliot), data acquisition and analytics increasingly forms the bedrock of not only the global economy, but domains of human experience.

Big data technologies are often claimed to be more truthful, efficient, and objective compared to the biased and error-prone tendencies of human decision-making. Its critics, however, have shown this assumption to be outrightly false – particularly for people of colour. Safiya Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression highlights cases of algorithmically driven data failures which underscore the ways in which sexism and racism are fundamental to online corporate platforms like Google. Cathy O’Neil’s Weapons of Maths Destruction addresses the myriad ways in which big data analytics tend to disadvantage the poor and people of colour under the auspice of objectivity. Such critiques often approach big data through the lens of bias – either bias embedded in views of the dataset or algorithm creator, or bias ingrained in the data itself. In other words, biased data will subsequently produce biased outcomes – garbage in, garbage out. Demands for inclusion or “unbiased data”, however, often fail to address the racialised dialectic between inside and outside, human and Other. As Ramon Amaro argues, “to merely include a representational object in a computational milieu that has already positioned the white object as the prototypical characteristic catalyses disruption superficially” (53). From this perspective, the racial other is positioned in opposition to the prototypical classification, which is whiteness, and is thus seen as “alientated, fragmented, and lacking in comparison” (Amaro 53). If the end goal is inclusion, Amaro follows, what about a right of refusal to representation? This question is particularly pertinent in a context where inclusion also means exposure to heightened forms of surveillance for racialised communities, particularly in the context of policing (Lee and Chin).

Relatedly, the language of bias, inclusion, and exclusion does not account for the ways in which big data analytics are producing new racial classifications emerging not from data inputs, but within correlative models themselves. As Thao Than and Scott Wark suggest, “the application of inductive techniques to large data sets produces novel classifications. These classifications conceive us in new ways – ways that we ourselves are unable to see” (3). Following Gilroy’s idea that changes in perceptuality led by the technological revolution of the 21st century require a reimagination of race, or a repudiation of it altogether, Than and Wark claim that racialism is no longer solely predicated on visual hierarchies of the body, but rather “emerges as an epiphenomenon of automated algorithmic processes of classifying and sorting operating through proxies and abstractions” (2). This phenomenon is what they term racial formations as data formations. That is, racialisation shaped by the non-visible processing of data-generated proxies. Drawing from examples such as Facebook’s now disabled “ethnic affinity“ function, which classed users by race simply by analysing their behavioural data and proxy indicators, such as language, ‘likes’, and IP address – Than and Wark show “that in the absence of explicit racial categories, computational systems are still able to racialize us” – though this may or may not map onto what one looks like (3). While the datafication of racial formations may deepen already-present inequalities for people of colour, these formations have a much more pernicious function: the transformation of racial category itself.

Can these emergent formations culled from the insights of big data be called ‘race’, or do we need a new kind of language to account for technologically induced shifts in racial perception and scale? Further, are processes of computational induction ‘racialising’ if they are producing novel classifications which often map onto, but are not constrained by previous racial categories? As Achille Mbembe notes, these questions must also be considered in the context of 21st globalisation and the encroachment of neoliberal logics into all facets of life, such that “all events and situations in the world of life can be assigned a market value” (Vogl 152). Our contemporary context of globalised inequality is increasingly predicated on what Mbembe describes as the “universalisation of the black condition”, whereby the racial logics of capture and predication which have shaped the lives of black people from the onset of the transatlantic slave trade, “have now become the norm for, or at least the lot of, all of subaltern humanity” (Mbembe 4). Here, it is not the biological construct of race per se that is activated in the classifying logics of capitalism and emergent technologies, but rather, the production of “categories that render disposable populations disposable to violence” (Lloyd 2). In other words, 21st century racialism is circumscribed by differential relations of human value determined by the global capitalist order. Nonetheless, these new classifications retain the pervasive logic of difference and division, reconfiguring the category of the disentitled, less-than-human Other in new formations. As Mbembe suggests, neither “Blackness nor race has ever been fixed”, but rather reconstitutes itself in new ways (6). In the next section, I turn to predictive policing technology to parse the ways in which data regimes are mapping new terrains upon which racial formations are produced and sustained.

The Problem of Prediction: Data-led policing in the U.S.

Multiple vectors of racialism, both old and new, visual and post-visual, large and small-scale, play out in the optics of predictive policing technology. Predictive policing software operates by analysing vast swaths of criminological data to forecast when and where a crime of a certain nature will take place, or who will commit it. The history of data collection is deeply entwined with the project of policing and criminological knowledge, and further, the production of race itself. As Autumn Womack shows in her analysis of “the racial data revolution” in late nineteenth century America, "data and black life were co-constituted in the service of producing a racial regime” (15). Statistical attempts to measure and track the movements of black populations during this period went hand in hand with sociological and carceral efforts to regulate and control black life as an object of knowledge. Policing was and continues to be central to this disciplinary project. As R. Joshua Scannell powerfully argues, “Policing does not have a “racist history.’ Policing makes race and is inextricable from it. Algorithms cannot ‘code out’ race from American policing because race is a policing technology, just as policing is a bedrock racializing technology” (108). Like data, policing and the production of race difference co-constitute one another. Predictive policing thus cannot be analysed without accounting for entanglements between data, carcerality, and racialism.

Computational methods were integrated into American criminal justice departments beginning in the 1960’s. Incited by America’s “War on Crime”, the densification of urban areas following the Great Migration of African Americans to Northern cities, and the economic fall-out from de-industrialisation, criminologists began using data analytics to identify areas of high-crime incidence from which police patrol zones were constructed. This strategy became known as hot spot criminology. By 1994, the New York City Police Department (NYPD) had integrated CompStat, the first digitised, fully automated data-driven performance measurement system into its everyday operations. CompStat is now employed by nearly every major urban police department in America. Beginning in 2002, the NYPD began using statistical insights digitally generated by CompStat to draw up criminogenic “impact zones” – namely low income, black neighbourhoods – that would be subject to heightened police surveillance. As Brian Jefferson observes, the NYPD’s statistical strategy “was deeply wound up in dividing urban space according to varying levels of policeability” (116). Moreover, impact zones “provided not only a scientific pretext for inundating negatively racialized communities in patrol units but also a rationale for micromanaging them through hyperactive tactics” such as stop-and-frisk searches (Jefferson 117). Between 2005 and 2006, the NYPD conducted 510,000 stops in impact zones – a 500% increase from the year before. The analytically derived "impact zone” can thus be understood as a bordering technology – one that sorts and divides civilian populations from those marked by higher probabilities of risk, and thus suspicion.

Policing has only grown more reliant on insights culled from predictive data models. PredPol – a predictive policing company that was developed out of the Los Angeles Police Department in 2009 – forecasts crimes based on crime history, location, and time of day. HunchLab, the more “holistic” successor of PredPol, not only considers factors like crime history, but uses using machine learning approaches to assign criminogenic weights to data “associated with a variety of crime forecasting models” such as the density of “take-out restaurants, schools, bus stops, bars, zoning regulations, temperature, weather, holidays, and more” (Scannel 117). Here, it is not the omniscience of panoptic vision, or the individualising enactment of power that characterises Hunchlab’s surveillance software, but the punitive accumulation of proxies and abstractions in which “humans as such are incidental to the model and its effects” (Scannel 118). Under these conditions, for example, “criminality increasingly becomes a direct consequence of anthropogenic climate change and ecological crisis” (Scannel 122).

Data-driven policing is often presented as the objective antidote to the failures of human-led policing. However, in a context where black and brown people around the world are historically, and contemporaneously subjected to disproportionate police surveillance, carceral punishment, and state-sponsored violence, input data analysed by predictive algorithms often perpetuates a self-reinforcing cycle through which black communities are circuitously subjected to heightened police presence. As sociologist Sarah Brayne explains, “if historical crime data are used as inputs in a location-based predictive policing algorithm, the algorithm will identify areas with historically higher crime rates as high risk for future crime, officers will be deployed to those areas, and will thus be more likely to detect crimes in those areas, creating a “self- fulfilling statistical prophecy” (109).

Beyond this critical cycle of ‘garbage in, garbage out,’ Than and Wark’s conceptualisation of racial formations as data formations provides insight into the ways in which predictive policing instils racialisation as a post-visual epiphenomenon of data-generated proxies. While the racist outcomes of data-led policing certainly manifest in the lived realities of poor and negatively racialised communities, predictive policing necessarily relies upon data-generated, non-visual proxies of race – postcode, history of contact with the police, geographic tags, distribution of schools or restaurants, weather, and more. Such technologies demonstrate how different valuations of risk that “render disposable populations disposable to violence” are actively produced not merely through historical data, but in the correlative models themselves (Lloyd 2). While these statistically generated “patrol zones” tend to map onto historically racialised communities, this process of racialisation does not necessarily correspond to the visual, or phenotypic signifiers of race. What emerges in these correlative models are novel kinds of classifications that arise from probabilistic inferences of suspicion through which subjects – often racial minorities – are exposed to heightened surveillance and violence. As Jefferson suggests, “modernity’s racial taxonomies are not vanishing through computerization; they have just been imported into data arrays” (6). The question remains, as neighbourhoods and ecologies, and those who dwell within them, are actively transcribed into newly ‘raced’ data formations, what becomes of the body in this post-visual shift?

2015

This provocation returns us to American Artist’s video installation, 2015. From the onset of the work, the camera’s objectivity is consistently brought into question. Gesturing towards the frame as an architectural narrowing of positionality, the constricted, stationary viewpoint of the camera fixed onto the dashboard of the police car positions the viewer within the uncomfortable observatory of the surveillant police apparatus. The window is imaged as an enclosure which frames the disproportionate surveillance of black communities by police. The world view here is captured from a single axis, a singular ideological vantage point, as an already known world of city landscape passes ominously through the window’s frame of vision. The frame’s hyper-selectivity, an enduring object of scrutiny in the field of evidentiary image-making, and visuality more broadly, is always implicated in the politics of what exists beyond its view, thus interrogating the assumed indexicality, or visual truth of the moving image.

The frame’s ambiguous functionality is made palpable when the car pulls over to stop. Over the din of a loud police siren, we hear a car door open and shut as the disembodied police officer climbs out of the car to survey the scene. Never entering the camera’s line of vision, the imagined, diegetic space outside the frame draws attention to the occlusive nature of the recorded seen-and heard. As demonstrated in the countless acquittals of police officer’s guilty of assaulting or killing unarmed black people, even when death occurs within the “frame” of a surveillance camera, dash cam or a civilian bystander, this visual record remains ambiguous and is rarely deemed conclusive. Consider the cases of Eric Garner, Philando Castille, or Rodney King, a black man whose violent assault by a group of LAPD officers in 1991 was recorded by a bystander and later used as evidence in the prosecution of King’s attackers. Despite the clear visual evidence of what took place, it was the Barthesian concept of the “caption” – the contextual text which rationalises or situates an image within a given ontological framework – that led to the officer’s acquittal. As Brian Winston notes, “what was beyond the frame containing “the recorded ‘seen-and-heard’” was (or could be made to seem) crucial. This is always inevitably the case because the frame is, exactly, a “frame” – it is blinkered, excluding, partial, limited” (614). This interrogation of the fallacies of visual “evidence” is a critical armature of 2015’s intervention, one that interrogates the underlying assumptions of visuality and perception in surveillance apparatuses, constructing the frame of the police window not as a source of visible evidence, but that which obfuscates, conceals, or obstructs.

Beyond the visual, other lives of data further complicate the already troubled notion of the visible as a stable category. As Sharon Lin Tay argues, “Questions of looking, tracking, and spying are now secondary to, and should be seen within the context of, network culture and its enabling of new surveillance forms within a technology of control.” (568). In other words, scopic regimes that implicitly inform the surveillance context are increasingly subsumed by the datasphere from which multiple stories and scenes may be spun. “Evidence” no longer relies solely on a visual account of “truth”, but rather on a digital record of traces. American Artist’s representation of predictive policing software and technologies of biometric identification alludes to the scope in which data is literally superimposed onto our own frame of vision. Predicting our locations, consumption habits, political views, credit scores, and criminal intentions, analytic predictive technologies condense potential futures into singular outputs. As the police car follows the erratic route of its predictive policing software on the open road, we are simultaneously made aware of a future which is already foreclosed.

Here, as 2015 so aptly suggests, the life of data exists beyond our frame of view but increasingly determines what occurs within it. Data is the text that literally “captions” our lives and identities. In zones deemed high-risk for crime by analytic algorithms, subjects are no longer considered civilians, but are hailed and interpolated as criminalised suspects through their digital subjectification. As the police car cruises through Brooklyn’s sparsely populated streets and neighbourhoods in the early morning, footage of people going about their daily business morphs into an insidious interrogation of space and mobility. As the work provocatively suggests, predictive policing construct zones of suspicion and non-humanity through which the body is interrogated and brought into question. In identifying the body as “threat” by virtue of its geo-spatial location in a zone wholly constructed by the racializing history of policing data, the racial body is recoded, not as a necessarily phenotypic entity, but as a product of data. American Artist’s 2015 palpably coneys race as lived through data, shaping who, and what comes into the frame of the surveillant apparatus. The unadorned message: race is produced and sustained as a product of data.

Yet, at the same time, the work’s aesthetic intervention interrogates the enduring physiological nature of visual racialism through the coding of the body. As the police car cruises through the highlighted zones of predicted crime, select passers-by are singled out and scanned by a facial recognition device. This visceral reference to biometric identification – reading the body as the site and sign of identity – complicates the claim that the primordial, objectifying force of visual evidence are transcended by neutral seeming post-visual data apparati. Biometric systems of measurement, such as facial templates or fingerprint identification, are inherently tied to older, eighteenth and nineteenth century colonial and ethnographic regimes of physiological classification that aimed to expose a certain truth about the racialized subject through their visual capture. Contemporary biometric technologies, as Simone Browne argues, retain the same systemic logics of their colonial predecessors, “alienating the subject by producing a truth about the racial body and one’s identity (or identities) despite the subject’s claims” (110). It has been repeatedly shown, for example, that facial recognition software demonstrates bias against subjects belonging to specific racial groups, often failing to detect or misclassifying darker-skinned subjects, an event that the biometric industry terms a “failure to enrol” (FTE). Here, blackness is imaged as outside the scope of human recognition, while at the same time, black people are disproportionately subjected to heightened surveillance by global security apparatuses. This disparity shows that while forms of racialisation are increasingly migrating to the terrain of the digital, race still inheres, even if residually, as an epidermal materialisation in the biometric evidencing of the body.

In American Artist’s 2015, extant tension between data and the lived, phenotypic, or embodied constitution of racialism suggests that these two racializing formats interlink and reinforce each other. By evidencing the racial body, on one hand as a product of data, and on the other, an embodied, physiological construction of cultural and scientific ontologies of the Other, American Artist makes visible the contemporary and historical means through which race is lived and produced. By calling into question the visual and digital ways the racial body is made to evidence its being-in-the-world, Artist challenges and disrupts the evidentiary logics of surveillance apparatuses – that being, what Catherine Zimmer describes as the “production of knowledge through visibility” (428). By entangling racializing forms of surveillance within a realist documentary-like coded format, American Artist calls into question what it means to document, record, or survey within the frame of moving images. As data increasingly guides where we go, what we see, and whose bodies come into question, claims on the recorded seen and heard, as well as the digitally networked, must continually be interrogated. In the context of our current democratic crisis, where the volatile distinctions between “fact” and “fiction” have produced a plethora of unstable meanings, American Artist’s artistic 2015 is a prime example of emergent activist political intervention that interrogates the underlying assumption of documentary objectivity in both cinematic and data-driven formats, subverting the racial logics that remain imbricated within visual and post-visual systems of classifications.

Conclusion

This article explores the shifting terrain of racial discourse in the age and scalar magnitude of big data. Drawing from Paul Gilroy’s periodisation of racialism from Euclidian anatomy of the 19th century to the genomic revolution of the 1990’s, I show that race has always been deeply entwined with questions of scale and perception. Gilroy observed that emergent digital technologies afford potentially new ways of seeing the body, and subsequently, conceiving humanity in novel scales detached from the visual. Similar insights inform Than and Wark’s prescient account of racial formations as data formations – the idea that race is increasingly being produced as a cultivation of data-driven proxies and abstractions. In the context of ongoing logics of contemporary race, American Artist’s 2015 returns consideration to the ways in which residual, and emergent characteristics of racialism are embedded in everyday systems of predictive policing technology. Through multimedia intervention, Artist’s video work conveys racialism not as a single, static entity, but as a historical structure that mutates and evolves algorithmically across an ever-shifting geopolitical landscape of capital and power. In this instance, American Artist orchestrates one critical means to grasp racialism’s multiple forms, past and present, visual, and otherwise, towards future modalities and determinations not yet realised.

Works cited

Amaro, Ramon. The Black Technical Object: On Machine Learning and the Aspiration of Black Being. Sternberg Press, 2023.

Amoore, Louise. “Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror.” Political geography 25.3 (2006): 336–351.

Berman, Eli et al. Small Wars, Big Data: The Information Revolution in Modern Conflict. Princeton University Press, 2018.

Bhutta, Neil, Aurel Hizmo, and Daniel Ringo. “How Much Does Racial Bias Affect Mortgage Lending? Evidence from Human and Algorithmic Credit Decisions,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-067. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2022.

Brayne, Sarah. Predict and Surveil: Data, Discretion, and the Future of Policing. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Discriminating Data: Correlation, Neighborhoods, and the New Politics of Recognition. The MIT Press, 2021.

DiCaglio, Joshua. Scale Theory : a Nondisciplinary Inquiry. University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Doug Laney. “3D Data Management: Controlling Data Volume, Velocity, and Cariety”, Gartner, File No. 949, 6 February 2001, http://blogs.gartner.com/doug-laney/files/2012/01/ad949-3D-Data-Management-Controlling-Data-Volume-Velocity-and-Variety.pdf.

Gilroy, Paul. “Race Ends Here.” Ethnic and racial studies, vol 21, no. 5, 1998, pp. 838–847.

Gilroy, Paul. “Race and Racism In the Age of Obama”. The Tenth Annual Eccles Centre for American Studies Plenary Lecture given at the British Association for American Studies Annual Conference, 2013.

Jefferson, Brian. Digitize and Punish: Racial Criminalization in the Digital Age. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Lloyd, David. Under Representation: The Racial Regime of Aesthetics. New York: Fordham University Press, 2018.

Macnish, Kevin, and Jai Galliott, editors. Big Data and Democracy: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Mbembe, Achille. 2013. Critique of Black Reason. Duke University Press.

Melamed, Jodi. 2011. Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism . University of Minnesota Press.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018

Obermeyer. Ziad et al. “Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations” Science, 2019, pp. 447-453.

O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Allen Lane, 2016.

Rothstein, M. “Big Data, Surveillance Capitalism, and Precision Medicine: Challenges for Privacy.” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 49, no. 4, 2021, pp. 666-676..

Saini, Angela. Superior: the Return of Race Science. Beacon Press, 2020.

Scannel, R. Joshua. “This Is Not Minority Report predictive policing and population racism”. Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want, edited by Ruha Benjamin. Princeton University Press, 2022, pp. 106-129.

Than, Thao, and Scott Wark. “Racial formations as data formations.” Big Data & Society, 2021, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1-5.

Vogl, Joseph.Joseph Vogl. Le spectre du capital. Diaphanes, 2013.

Winston, Brian. “Surveillance in the Service of Narrative”. A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film, edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow. John Wiley & Sons, 2015, pp. 611-628.

Womack, Autumn. The Matter of Black Living: the Aesthetic Experiment of Racial Data, 1880-1930. The University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Završnik, Aleš. “Algorithmic Justice: Algorithms and Big Data in Criminal Justice Settings.” European journal of criminology, vol 18, no. 5, 2021, pp. 623–642.

Susanne Förster

The Bigger the Better?!

The Size of Language Models and the Dispute over Alternative Architectures

The Bigger the Better?! The Size of Language Models and the Dispute over Alternative Architectures

Abstract

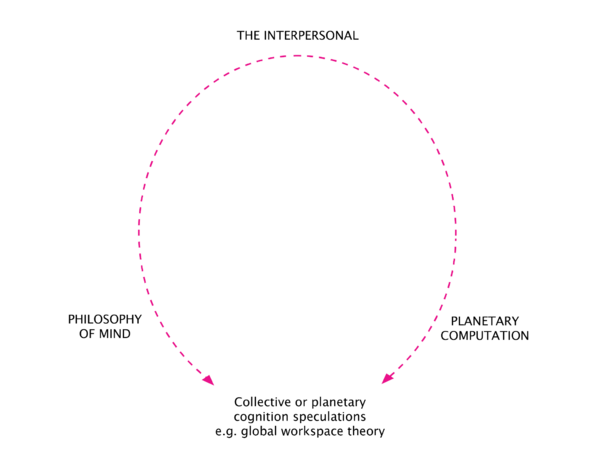

This article looks at a controversy over the ‘better’ architecture for conversational AI that unfolds initially along the question of the ‘right’ size of models. Current generative models such as ChatGPT and DALL-E follow the imperative of the largest possible, ever more highly scalable, training dataset. I therefore first describe the technical structure of large language models and then address the problems of these models which are known for reproducing societal biases or so-called hallucinations. As an ‘alternative’, computer scientists and AI experts call for the development of much smaller language models linked to external databases, that should minimize the issues mentioned above. As this paper will show, the presentation of this structure as ‘alternative’ adheres to a simplistic juxtaposition of different architectures that follows the imperative of a computable reality, thereby causing problems analogous to the ones it tried to circumvent.

In recent years, increasingly large, complex and capable machine learning models such as the GPT model family, DALL-E or Stable Diffusion have become the super trend of current (artificially intelligent) technologies. Trained on identifying patterns and statistical features and thus intrinsically scalable, the potential of large language models is seen as based on their generative capabilities to produce a wide range of different texts and images.

The monopolization and concentration of power within a few big tech companies such as Google, Microsoft, Meta and OpenAI that accompanies this trend is promoted by the enormous economic resources afforded by the models’ training processes (see Luitse and Denkena). The risks and dangers of this big data paradigm have been stressed widely: The working conditions and invisible labor that goes into the creation of AI and ensures its fragile efficacy has been addressed in the context of click-work or content moderation (f.e., Irani; Rieder and Skop). In Anatomy of an AI System, Kate Crawford’s and Vladan Joler (Crawford and Joler) detailed the material setup of a conversational device and traced the far fetching origins of its hardware components and working conditions. Critical researchers have also pointed out how the composition of training data has resulted in the reproduction of societal biases. Crawled from the Internet, the data and thus the generated language mainly represent hegemonic identities whilst discriminating against marginalized ones (Benjamin). Moreover, the infrastructure needed to train these models requires huge amounts of computing power and has been linked to a heavy environmental footprint: The training of a big Transformer model emitted more than 50 times the amount of carbon dioxide than an average human per year (Strubell et al., Bender et al.). Criticizing this seemingly inevitable turn to ever larger language models and the far-reaching implications of this approach for both people and the environment, Emily Bender et al., published their now-famous paper On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models be Too Big? in March 2021 (Bender et al.). Two of the authors, Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell, both co-leaders of Google’s Ethical AI Research Team, were fired after publishing this paper against Google’s veto.

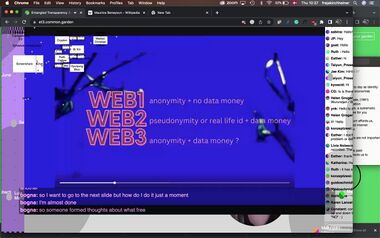

The dominance of the narrative of "scalability, [...], the ability to expand - and expand, and expand" (Tsing 5) deep learning models – especially by big tech companies – has clouded the view for alternative approaches. With this paper, I will look at claims and arguments for different architectures of conversational AI by first reconstructing the technical development of generative language models. I will further trace the reactions to errors and problems of generative large language models and the dispute over the ‘proper’ form of artificial intelligence between proponents of connectionist AI and machine learning approaches on the one side and those of symbolic or neurosymbolic AI defending the need for ‘smaller’ language models linked to external knowledge databases on the other side. This debate represents a remarkable negotiation about forms of ‘knowledge representation’ and the question of how language models should (be programmed to) ‘speak’.

Initially, the linking of smaller language models with external databases promising accessibility, transparency and changeability had subversive potential for me because it pledged the possibility of programming conversational AI without access to the large technical infrastructure it would take to train large language models (regardless of whether those models should be built at all). As I will show in the following, the hybrid models presented as an alternative to large language models also harbor dangers and problems, which are particularly evident in an upscaling of the databases.

In need of more data

Since its release in November 2022, the dialogue-based model ChatGPT generated a hype of unprecedented dimensions. Provided with a question, exemplary text or code snippet, ChatGPT mimics a wide range of styles from different authors and text categories such as poetry and prose, student essays and exams or code corrections and debug logs. Soon after its release, the end of both traditional knowledge and creative work as well as classical forms of scholarly and academic testing seemed close and were heavily debated. Endowed with emergent capabilities, the functional openness of these models is perceived as both a potential and a problem as they can produce speech in ways that appears human but contradicts human expectations and sociocultural norms. ChatGPT was also called a bullshit generator (McQuillan): Bullshitters, as philosopher Harry Frankfurt argues, are not interested in whether something is true or false, nor are they liars who would intentionally tell something false, but are solely interested in the impact of their words (Frankfurt).

Generative large language models such as OpenAI’s GPT model family or Google’s BERT and LaMDA are based on a neural network architecture – a cognitivist paradigm based on the idea of imitating the human brain logically-mathematically and technically as a synonym for "intelligence", but usually without taking into account physical, emotional and social experiences (see Fazi). In the connectionist AI approach, ‘learning’ processes are modeled with artificial neural networks consisting of different layers and nodes. They are trained to recognize similarities and representations within a big data training set and compute probabilities of co-occurrences of individual expressions such as images, individual words, or parts of sentences. After symbolic AI was long considered as the dominant paradigm, the "golden decade" of deep neural networks – also called deep learning – dawned in the 2010s, according to Jeffrey Dean (Dean). 2012 is recognized as the year in which deep learning gained acceptance in various fields: On the one hand, the revolution of speech recognition is associated with Geoff Hinton et al., on the other hand, the winning of the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge with the help of a convolutional neural network represented a further breakthrough (Krizhevsky et al.). Deep learning neural networks with increasingly more interconnected nodes (neurons) and layers and powered by newly developed hardware components enabled huge amounts of compute power became the standard.

Another breakthrough is associated with the development of the Transformer Network architecture, introduced by Google in 2017. The currently predominant architecture for large language models is associated with better performance due to a larger size of the training data (Devlin et al.). Transformers are characterized in particular by the fact that computational processes can be executed in parallel (Vaswani et al.), a feature that has significantly reduced the models’ training time. Building on the Transformer architecture, OpenAI introduced the Generative Pre-trained Transformer model (GPT) in 2018, a deep learning method which again increased the size of the training datasets (Radford et al., “Improving Language Understanding”). Furthermore, OpenAI included a process of pre-training, linked to a generalization of the model and an openness towards various application scenarios, what is thought to be achieved through a further step of optimization, i.e., the fine-tuning. At least with the spread of the GPT model family, the imperative of unlimited scalability of language models has become dominant. This was especially brought forward by Physics (Associate) Professor and Entrepreneur Jared Kaplan and OpenAI, who identified a set of ‘scaling laws’ for neural network language models, stating that the more data available for training, the better the performance thereof (Kaplan et al.). OpenAI has continued to increase the size of its models: While GPT-2 with 1.5 billion parameters (a type of variable learned in the process of training) was 10 times the size of GPT-1 (117 million parameters), it was far surpassed by GPT-3 with a scope of 175 trillion parameters. Meanwhile, OpenAI has transformed from a startup promoting the democratization of artificial intelligence (Sudmann) to a 30 billion dollar company (Martin) and from an open source community to a closed one. While OpenAI published research papers with the release of previous models describing the structure of the models, the size and composition of the training data sets, and the performance of the models in various benchmark tests, much of this information is missing from the paper on GPT-4.

On errors and hallucinations

Generative language models, however, are being linked – above all by developers and computer scientists – to a specific kind of ‘error’: “[I]t is also apparent that deep learning based generation is prone to hallucinate unintended texts”, Ji et al. write in a review article collecting research on hallucination in natural language generation (Ji et al.). According to the authors, the term hallucination has been used in the field of computer visualization since about 2000, referring to the intentionally created process of sharpening blurred photographic images, and only recently changed to a description of an incongruence between image and image description. Since 2020, the term has also been applied to language generation, however not for describing a positive moment of artificial creativity (ibid.): Issued texts that appear sound and convincing in a real-world context, but whose actual content cannot be verified, are referred to by developers as ‘hallucinations’ (ibid., 4). In this context, hallucination refers not only to factual statements such as dates and historical events or the correct citation of sources; it is equally used for editions of non-existent sources or the addition of aspects in a text summary. While the content is up for discussion, the language form may be semantically correct and convincing, resulting in an apparent trust in the model or its language output.

For LeCun, Bengio and Hinton, “[r]epresentation learning is a set of methods that allows a machine to be fed with raw data and to automatically discover the representations needed for detection or classification. Deep-learning methods are representation-learning methods with multiple levels of representation, obtained by composing simple but non-linear modules that each transform the representation at one level (starting with the raw input) into a representation at a higher, slightly more abstract level.” (LeCun et al. 436). In technical terms, hallucination thus refers to a translation or representation error between the source text or ‘raw data’ [sic] on the one hand and the generated text, model prediction or ‘representation’ on the other. Furthermore, another source of hallucinations is located in outdated data, causing the (over time) increasing production of factually incorrect statements. This ‘error’ is explicitly linked to the large scale of generative models: Since the training processes of these models are complex and expensive and thus seldomly repeated, the knowledge incorporated – generally – remains static (Ji et al.) However, with each successive release of the GPT model family, OpenAI proclaims further minimization of hallucinations and attempts to prevent programs from using certain terms or making statements that may be discriminatory or dangerous, depending on the context, through various procedures that are not publicly discussed (see Cao).

From the definitions of representation learning, hallucination, and the handling of this 'error', a number of conclusions can be drawn that are instrumental to the discourse on deep learning and artificial intelligence: The representation learning method assumes that it does not require any human intervention to recognize patterns in the available data, to form categories and make statements that are supposed to be consistent with the information located in the data. Both the data and the specific outputs of the models are conceived as universally valid. In this context, hallucination remains a primarily technical problem presented as technically solvable, and in this way it is closely linked to a promise of scaling: With the reduction of (this) error, text production seems to become autonomous, universal, and openly applicable in different settings.

On data politics

The assumption that data represent a ‘raw’ and objective found reality, which can be condensed and generated into a meaningful narrative through various computational steps, has been criticized widely (e.g. Boellstorff; Gitelman and Jackson). It is not only the composition of the data itself that is problematic, but equally the categories and patterns of meaning generated by algorithmic computational processes, which reinforce the bias – inevitably (see Jaton) – found in the data and make it once more effective (Benjamin; Noble). Technical computations adhere to an objectivity and autonomy that pushes human processes of selection and interpretation of the data into the background, presenting them instead as ‘found’ and ‘closed’ (e.g., boyd and Crawford; Kitchin). Building on a rich tradition of science and technology studies that highlighted the socio-technical co-production of human, natural and technical objects (f.e. Knorr Cetina, Latour and Woolgar), Adrian Mackenzie has introduced the term 'machine learner' to refer to the entanglement of "humans and machines or human-machine relations […] situated amidst these three accumulations of settings, data and devices" (Mackenzie 23).

"[Big] data," as Taş writes, "are a site of political struggle." (Taş 569). This becomes clear not only through the public discussion of generative models and the underlying question of which statements language models are allowed to make. At the latest with the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, it was publicly debated which responses of the model were considered unexpected, incorrect or contrary to socio-cultural norms. Generative models have been tested in a variety of ways (Marres and Stark): The term 'jailbreaking' for example, denotes a practice in which users attempt to trick the model to create outputs that are restrained by the operating company's policy regulation. These include expressions considered as discriminating and obscene or topics such as medicine, health or psychology. In an attempt to circumvent these security measures, jailbreaking exposes the programmed limitations of the programs. Moreover, it also reveals what is understood by the corporations as the ‘sayable’ and the ‘non-sayable’ (see Foucault). This is significant insofar as these programs have already become part of everyday use, and the norms, logics, and limits inherent in them have become widely effective. In only five days after its release, ChatGPT had already reached one million users (Brockman). As foundation models (Bommasani et al.), OpenAI's GPT models and DALL-E are built into numerous applications, as are Google's BERT and LaMDA. Recently, the use of ChatGPT by a US lawyer or the demand to use the program in public administration (Armstrong; dpa/lno) was publicly discussed. These practices and usage scenarios make it clear that – practically – generative models represent technical infrastructures that are privately operated and give the operating big tech companies great political power. The associated authority in defining the language of these models but also in guiding politics recently became visible in a number of instances:

In an open letter, published in March 2023 on the website of the Future of Life Institute, AI researchers including Gary Marcus, Yoshua Bengio, and Yann LeCun – the latter working for Meta – as well as billionaire Elon Musk, urged for a six-month halt of training of models larger than GPT-4 (Future of Life Institute, “Pause Giant AI Experiments”). “Powerful AI systems”, they wrote, “should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable.” (ibid.), referring to actual and potential consequences of AI technology, such as the spread of untrue claims or the automation and loss of jobs. Also arguing with the creation of fake content, impersonation of others, and on the assumption that generated text is indistinguishable from that of human authors, OpenAI had initially restricted access to GPT-2 in 2019 (Radford et al., "Better Language Models"). Both the now more than 31,000 signatories of the open letter (as of June 2023) and OpenAI itself argue not against the architecture of the models, but for the use of so-called security measures. The Future of Life Institute writes in its self-description: “If properly managed, these technologies could transform the world in a way that makes life substantially better, both for the people alive today and for all the people who have yet to be born. They could be used to treat and eradicate diseases, strengthen democratic processes, and mitigate - or even halt - climate change. If improperly managed, they could do the opposite […], perhaps even pushing us to the brink of extinction.” (Future of Life Institute, “About Us”).

As this depiction richly illustrates, the Future of Life Institute is an organization dedicated to ‘long-termism’, an ideology that promotes posthumanism and the colonization of space (see MacAskill), rather than addressing the multiple contemporary crises (climate, energy, corona pandemic, global refugee movements, and wars) promoted by global financial market capitalism that profoundly reinforce social inequalities. Moreover, "AI doomsaying," i.e., the narrative of artificial intelligence as an autonomously operating agent whose power grows with access to more and more data and ever-improving technology, and whose workings remain inaccessible to human understanding as a black-box, further enhances the influence and power of big tech companies by attributing to their products the power "to remake - or unmake - the world." (Merchant).

On the linking of language models and databases

Taking up criticism of large language models such as the ecological and economic costs of training or the output of unverified or discriminating content, there are debates and frequent calls to develop fundamentally smaller language models (e.g., Schick and Schütze). Among others, David Chapman, who together with Phil Agre developed alternatives to prevailing planning approaches in artificial intelligence in the late 1980s (Agre and Chapman), recently called for the development of the ‘smallest language models possible’: "AI labs, instead of competing to make their LMs bigger, should compete to make them smaller, while maintaining performance. Smaller LMs will know less (this is good!), will be less expensive to train and run, and will be easier to understand and validate." (Chapman). More precisely, language models should "'know' as little as possible-and retrieve 'knowledge' from a defined text database instead." (ibid.). In calling for an architectural separation of language and knowledge, Chapman and others tie in with long-running discussions in phenomenology and pragmatism as well as those in formalism and the Theory of Mind.

Practices of data collection, processing and analysis are ubiquitous. Accordingly, databases are of great importance as informational infrastructures of knowledge production (cf. Nadim). They are not only "a collection of related data organized to facilitate swift search and retrieval" (ibid.), but also a "medium from which new information can be drawn and which opens up a variety of possibilities for shape-making" (Burkhardt, 15, my translation). Lev Manovich, in particular, has emphasized the principle openness, connectivity and relationality of databases (Manovich). In this view, databases appear as accessible and explicit, allowing for an easy interchangeability and expansion of entries, eventually permitting an upscaling of the entire architecture. Databases have been an important component of symbolic AI - also known as Good Old-Fashioned AI (GOFAI). While connectionist AI takes an inductive approach that starts from "available" data, symbolic AI is based on a deductive, logic- and rule-based paradigm. Matteo Pasquinelli describes it as a "top-down application of logic to information retrieved from the world" (Pasquinelli 2). Symbolic AI has become known, among other things , as a representation of ontologies or semantic webs.

Linking external databases with small and large language models emerges as a concrete answer to the problems of generative models, in which knowledge is understood as being ‘embedded’, and which – as illustrated by the example of hallucination – leads to various problems. While connectionist approaches have dominated in recent times, architectures of symbolic AI seem to reappear. The combination of databases and language models is already a common practice and currently discussed under the terms ‘knowledge-grounding’ or ‘retrieval augmentation’ (f.e. Lewis et al.). Retrieval-augmented means that in addition to fixed training datasets, the model also draws on large external datasets, an index of documents whose size can run into the trillions of documents. Meanwhile, models are called small(er) as they contain a small set of parameters in comparison to other models (Izacard et al.). In a retrieval process, documents are selected, prepared and forwarded to the language model depending on the context of the current task. With this setup, the developers promise improvements in efficiency in terms of resources such as the amount of parameters, ‘shots’ (the amount of correct information in the data sets), and corresponding hardware resources (ibid.).

In August 2022, MetaAI has already released Atlas, a small language model that was extended with an external database and which, according to the developers, outperformed significantly larger models with a fraction of the parameter count (ibid.). With RETRO (Retrieval-Enhanced Transformer), DeepMind has also developed a language model that consists of a so-called baseline model and a retrieval module. (Borgeaud et al.). In 2017, ParlAI, an open-source framework for dialog research founded by Facebook in 2017, presented Wizard of Wikipedia, a program – a benchmark task – to train language models with Wikipedia entries (Dinan et al.). They framed the problem of hallucination of, in particular, pre-trained Transformer models as one of updating knowledge. With this program, models are fine-tuned to extract information from database articles to be then casually inserted into a text or conversation without sounding like an encyclopedia entry themselves, thereby appearing semantically and factually correct. With the imagining of small models as ‘free of knowledge’, the focus changes: now not only size and scale are considered a marker of performance, but also the infrastructural and relational linking of language models to external databases. This linking of small language models to external databases thus represents a transversal shift in scale: While the size of the language models is downscaled, the linking with databases implies a simultaneous upscaling.

However, the ideal of an accessible and controllable database falls short where it is conceived as potentially endlessly scalable. It is questionable whether a possibly limitless collection of knowledge is still accessible and searchable or whether it does not transmute into its opposite: "When everything possible is written, nothing is actually said (Burkhardt 11, my translation). What prior knowledge of the structure and content of the database would accessibility require? The conditions of its architecture and the processes of collecting, managing and processing the information are quickly forgotten (ibid. 9f.) and obscure the fact that databases as sites of power also are exclusive and always remain incomplete. Inherent in the idea of an all-encompassing database is a universalism that assumes a generally valid knowledge and thus fails to recognize situated, embodied, temporalized, and hierarchized aspects. Following Wittgenstein, Daston has likewise illustrated that even (mathematical) rules are ambiguous and, as practice, require interpretation of the particular situation (Daston 10).

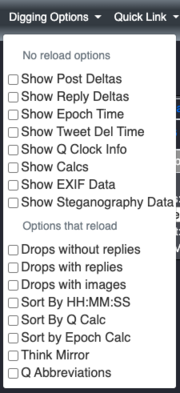

On disputes over better architectures

The narrative of the opposition of symbolic and connectionist AI locates the origin of this dispute in a disagreement between, on the one hand, Frank Rosenblatt and, on the other, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, who claimed in their book Perceptrons that neural networks could not perform logical operations such as the and/or (XOR) function (Minsky and Papert). This statement is often seen as causal for a cutback in research funding for connectionist approaches, later referred to as the ‘winter of AI’. (Pasquinelli 5). For Gary Marcus, professor of psychology and neural science, this dispute between the different approaches to AI continues to persist and is currently being played out at conferences, via Twitter and manifestos, and specifically on Noema, an online magazine of the Berggruen Institute, on which both Gary Marcus and Yann LeCun publish regularly. In an article titled AI is hitting a wall, Marcus calls for a stronger position of symbolic approaches and argues in particular for a combination of symbolic and connectionist AI (Marcus, “Deep Learning is Hitting a Wall”). For example, research by DeepMind had shown that "We may already be running into scaling limits in deep learning" and that increasing the size of models would not lead to a reduction in toxic outputs and more truthfulness (Rae et al.). Google has also done similar research (Thoppilan et al.). Marcus criticizes deep learning models for not having actual knowledge, whereas the existence of large, accessible databases of abstract, structured knowledge would be "a prerequisite to robust intelligence." (Marcus, “The Next Decade in AI”). In various essays, Gary Marcus recounts a dramaturgy of the conflict, with highlights including Geoff Hinton's 2015 comparison of symbols and aether, and calling symbolic AI "one of science's greatest mistakes " (Hinton), or the direct attack on symbol manipulation by LeCun, Bengio and Hinton in a 2016 manifesto for deep learning published in Nature (LeCun et al.). For LeCun, however, the dispute reduces to a different understanding of symbols and their localization. While symbolic approaches would locate them ‘inside the machine’, those of connectionist AI would be outside ‘in the world’. The problem of the symbolists would therefore lie in the problem of the "knowledge acquisition bottleneck", which would translate human experience into rules and facts and which could not do justice to the ambiguity of the world (Browning and LeCun). “Deep Learning is going to be able to do anything”, quotes Marcus Geoff Hinton (Hao).

The term ‘Neuro-Symbolic AI’, also called the ‘3rd wave of AI’, designates the connection of neural networks – which are supposed to be good in the computation of statistical patterns – with a symbolic representation. While Marcus is being accused of just wanting to put a symbolic architecture on top of a neural one, he points out that there would be already successful hybrids such as Go or chess – which are obviously games and not languages! – and that this connection would be far more complex as there would be several ways to do that, such as "extracting symbolic rules from neural networks, translating symbolic rules directly into neural networks, constructing intermediate systems that might allow for the transfer of information between neural networks and symbolic systems, and restructuring neural networks themselves" (Marcus, “Deep Learning Alone…”).

It’s not simply XOR

The linking of language models with databases, as shown above, is presented by Gary Marcus, MetaAI and DeepMind, among others, as a possibility to make the computational processes of the models accessible through a modified architecture. This transparency suggests at the same time the possibility of traceability, which is equated with an understanding of the processes, and promises a controllability and manageability of the programs. The duality presented in this context between uncontrollable, nontransparent and inaccessible neural deep learning architectures and open, conceivable and changeable databases or links to them, I want to argue, is fundamentally lacking in complexity. This assumes that the structure and content of databases are actually comprehensible. Databases, as informational infrastructures of encoded knowledge, must be machine-readable and are not necessarily intended for the human eye (see Nadim). Furthermore, this simplistic juxtaposition conceives of neural networks as black boxes whose ‘hidden layers’ between input and output inevitably defies access. In this way, the (doomsaying) narrative of autonomous, independent, and powerful artificial intelligence is further solidified, and the human work of design, the mostly precarious activity of labeling data sets, maintenance, and repair, is hidden from view.

Both the discourse about the better architecture and the signing of the open letter by ‘all parties’ also make clear that the representatives of connectionist AI and those of (neuro-)symbolic AI adhere to a technical solution to the problems of artificial intelligence. In either case, the world appears computable and thereby knowable and follows a colonial logic in this regard. Furthermore, the question of whether processes of learning should be simulated 'inductively' by calculating co-occurrences and patterns in large amounts of 'raw' data, or 'top-down' with the help of given rules and structures, touches at its core the 'problem' that the programs have no form of access to the world in the form of sensory impressions and emotions – a debate closely linked to the history of cybernetics and artificial intelligence (see f.e. Dreyfus). With the modeling and constant extension of the models with more data and other ontologies, the programs are built by following an ideal of human-like intelligence. In this perspective, the lack of access to the world is at the same time one of the causes of errors and hallucinations. Accordingly, the goal is to build models that speak semantically correctly and truthfully, while appearing as omniscient as possible, so that they can be easily used in various applications without relying on human correction: the models are supposed to act autonomously. Ironically, the attempt not to make mistakes reveals the artificiality of the programs.

The current hype around generative models like ChatGPT or DALL-E and the monopolization and concentration of power within a few corporations that accompanies it, has seemingly clouded the view for alternative approaches. Tsing's theory provided the occasion to look at the discourse around small, 'knowledge-grounded' language models, which - this was my initial assumption - oppose the imperative of constant scaling-up. Tsing writes that "Nonscalability theory is an analytic apparatus that helps us notice nonscalable phenomena" (Tsing 9). However, the architectures described here do not defy scalability; rather, a transversal shift occurs in that language models are scaled down and databases are scaled up at the same time. The object turned out to be more complex than the mere juxtaposition of scalable and nonscalable.

Conversational AI and generative models in particular are already an integral part of everyday processes of text and image production. The technically generated outputs produce a socially dominant understanding of reality, whose fractures and processes of negotiation are evident in the discussions about hallucinations and jailbreaking. It is therefore of great importance to follow and critically analyze both the technical (‘alternative’) architectures and affordances as well as the assumptions, interests, and power structures of the dominant (individual) actors (Musk, Altman, LeCun, etc.) and big tech corporations that are interwoven with them.

Works cited

Agre, Philip E., and David Chapman. "What Are Plans For?" Robotics and Autonomous Systems, vol. 6, no. 1, June 1990, pp. 17–34. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8890(05)80026-0.

Armstrong, Kathryn. "ChatGPT: US Lawyer Admits Using AI for Case Research". BBC News, 27 May 2023. www.bbc.com, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-65735769.

Bender, Emily M., et al. "On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜". Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, ACM, 2021, pp. 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Polity, 2019.

Boellstorff, Tom. "Making Big Data, in Theory:. First Monday, vol. 18, no. 10, 2013. mediarep.org, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i10.4869.

Bommasani, Rishi, et al. "On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models". ArXiv:2108.07258 [Cs], Aug. 2021. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258.

Borgeaud, Sebastian, et al. Improving Language Models by Retrieving from Trillions of Tokens. arXiv:2112.04426, arXiv, 7 Feb. 2022. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04426.

boyd, danah, and Kate Crawford. "Critical Questions for Big Data". Information, Communication & Society, vol. 15, no. 5, June 2012, pp. 662–79. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.678878.

Brockman, Greg [@gdb]. "ChatGPT just crossed 1 million users; it’s been 5 days since launch". Twitter, 5 December 2022, https://twitter.com/gdb/status/1599683104142430208.

Browning, Jacob, and Yann LeCun. "What AI Can Tell Us About Intelligence". Noema, 16 June 2022, https://www.noemamag.com/what-ai-can-tell-us-about-intelligence.

Burkhardt, Marcus. Digitale Datenbanken: Eine Medientheorie Im Zeitalter von Big Data. 1. Auflage, Transcript, 2015.

Cao, Sissi. "Why Sam Altman Won’t Take OpenAI Public". Observer, 7 June 2023, https://observer.com/2023/06/sam-altman-openai-chatgpt-ipo/.

Chapman, David [@Meaningness]. "AI labs should compete to build the smallest possible language models…". Twitter, 1 October 2022, https://twitter.com/Meaningness/status/1576195630891819008.

Crawford, Kate, and Vladan Joler. "Anatomy of an AI System". Virtual Creativity, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2019, pp. 117–20, https://doi.org/10.1386/vcr_00008_7.

Daston, Lorraine. Rules: A Short History of What We Live By. Princeton University Press, 2022.

Dean, Jeffrey. "A Golden Decade of Deep Learning: Computing Systems & Applications". Daedalus, vol. 151, no. 2, May 2022, pp. 58–74, https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01900.

Devlin, Jacob, et al. "BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding". Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2019, 2019, pp. 4171–86, https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423.pdf.

Dinan, Emily, et al. Wizard of Wikipedia: Knowledge-Powered Conversational Agents. arXiv:1811.01241, arXiv, 21 Feb. 2019. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.01241.

dpa/lno. "Digitalisierungsminister für Nutzung von ChatGPT". Süddeutsche.de, 4 May 2023, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/regierung-kiel-digitalisierungsminister-fuer-nutzung-von-chatgpt-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-230504-99-561934.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. What Computers Can’t Do. Harper & Row, 1972.

Fazi, M. Beatrice. "Beyond Human: Deep Learning, Explainability and Representation". Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 38, no. 7–8, Dec. 2021, pp. 55–77. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276420966386.

Foucault, Michel. Dispositive der Macht. Berlin: Merve, 1978.

Frankfurt, Harry G. On Bullshit. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Future of Life Institute. "About Us". Future of Life Institute, https://futureoflife.org/about-us/. Accessed 20 Apr. 2023.

Future of Life Institute. "Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter". Future of Life Institute, 22 Mar. 2023, https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/.

Gitelman, Lisa, and Virginia Jackson. "Introduction". Raw Data Is an Oxymoron, edited by Lisa Gitelman, The MIT Press, 2013, pp. 1–14.

Hao, Karen. "AI Pioneer Geoff Hinton: 'Deep Learning Is Going to Be Able to Do Everything'". MIT Technology Review, 3 Nov. 2020, https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/11/03/1011616/ai-godfather-geoffrey-hinton-deep-learning-will-do-everything/.