Pdf:Toward a Minor Tech: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

<div class="item" id="item-p1-b"> | <div class="item" id="item-p1-b"> | ||

<h1 class="inline"> | <h1 class="inline">Rendering Minor Worlds</h1> | ||

{{ Toward a Minor Tech:Teodora-500 }} | {{ Toward a Minor Tech:Teodora-500 }} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 12:14, 20 January 2023

Editorial

Toward a Minor Tech

Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox

The three characteristics of minor literature are the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective arrangement of utterance. Which amounts to this: that “minor” no longer characterises certain literatures, but describes the revolutionary conditions of any literature within what we call the great (or established).

–– Deleuze and Guattari, “Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature”

The 2023 edition of transmediale explores “how technological scale sets conditions for relations, feelings, democratic processes, and infrastructures.” (https://2023.transmediale.de/). This becomes apparent in the massification of images and texts, and the application of various scalar machine techniques that try to make these comprehensible for human and non-human readers.“There is a problem with scale”, as Anna Tsing puts it, in its connection to modernist master narratives that organise life on an increasingly globalised scale (the “bigness” of capitalism). Instead, she writes, we need to “notice” the small details and not assume that these need to be scaled up to be effective. In technical fields, there is a similar problem with scale, as Big Tech dominates, with ensuing environmental damage; big computing begets big data.

Following a process of open exchanges and a three-day research workshop in London, at LSBU and KCL, this publication brings together researchers who address the problems of technological scale, thinking through the potentials of 'the minor'; or what we are referring to as minor (or minority) tech – small tech that operates at human scale (more peer to peer than server-client) and stutters in its expression and application. As Marloes de Valk puts it in the Damaged Earth Catalog: “Small technology, smallnet and smolnet are associated with communities using alternative network infrastructures, delinking from the commercial Internet.” As such, the publication sets out to question the universal ideals of technology and its problems of scale, extending it to follow the three main characteristics identified in Deleuze and Guattari's essay, namely deterritorialization, political immediacy, and collective value.

Together authors address minor tech through its relation to big data, machine learning, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, blockchain mining, art worlds, global organisation of labour, extractions of natural resources, exploitation, energy consumption, trans-feminisms and decoloniality. Further issues that arise question, for instance, the dynamics between big data and small technology, attentive to what Cathy Park Hong calls “minor feelings” (that derive from racial and economic discrimination in society); how to bring together new material and minor cultural assemblages between humans and nonhumans, ecology, and technological infrastructure and systems; or, how this relates to minor practices and collective action.

This publication includes short articles that were written during the workshop and as a result of extensive peer exchange, and will be extended in the next issue of APRJA (http://aprja.net) to be published Summer 2023.

At the workshop, the authors and editors of this publication were joined by Marloes de Valk, Elena Marchevska, Tung-Hui Hu (at The Photographers' Gallery), and Manetta Berends & Simon Browne (Varia). The workshop and publication were supported by CSNI (London South Bank University), and SHAPE Digital Citizenship and Graduate School Arts (Aarhus University).

Camille Crichlow title

Camille Crichlow text

Rendering Minor Worlds

Rendering Minor Worlds

Teodora Sinziana Fartan

Critical renderings of speculative virtual imaginaries are increasingly emerging today as a form of collective utterance, a minority language that responds to the current states of emergency that we find ourselves in socially, politically, ecologically and technologically. The recent crystallization of immersive worlding as an experiential storytelling practice situates itself within the political context of resistance through its search for modes of being-otherwise. Kafka writes of literature that it should “affect us like a disaster, that grieves us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone”, foregrounding the affective and transformative power of storytelling - stretching forwards from his time to the present day, we see this practice of critical storytelling extended into the realm of virtual ecologies with artists like Ian Cheng, Lawrence Lek, David Blandy and Larry Achiampong, Sahej Rahal and Keiken formulating critiques of our contemporary context by producing minor worlds that speculatively explore alternative narratives. As Stengers urges us, these practices attempt to imagine “connections with new powers of acting, feeling, imagining, and thinking” and then prototype, hack, develop and render these into being.

A question, therefore emerges: how can we position and conceptualize these novel modes of expression that operate within the scales of virtual game spaces and their underlying networks of exchange? How can practices of worlding enable us to abandon “habitual temporalities and modes of being”, as Helen Palmer puts it, and think beyond ourselves, speculatively, towards possible futures and fictions?

The turn towards immersive world design is enabled by the recent deployment of game engine technologies towards critical digital experimentation, enabling artists to produce increasingly complex digital artifacts. Similarly to the properties of a minor language formulated by Deleuze and Guattari in their analysis of Kafka’s writing, today’s turn towards the production of virtual worlds as sites of alternative possibilities is deterritorializing the existing entertainment-centric and economically-driven mode of existence of immersive game productions. Within the parameters of the game engine itself, the various features, interfaces and functionalities of mainstream game design software are geared towards competitive ludic productions. However, with the increased accessibility of gaming technologies, we see the emergence of collective efforts to utilize game engines critically, towards the production of minority worlds, where the entertainment-focused properties of commodified games are replaced with experimental assemblages and their affect constellations.

When the majority language of the game engine is deployed into the minor territories of experiment and social critique, the audience's connection to political immediacy is facilitated through the experimental readings that are enabled. Pushing beyond the transformation of given content into the appropriate forms expected of major literature, worlding moves into the territory of minority expressions, where experimental and non-linear formats operate in networked and multifaceted ways, “speaking first and only conceiving afterwards”, as McLean infers. This study, therefore, aims to trace the ways in which new openings into alternative imaginaries are made possible on the shores of virtual worlds: how do virtual ecologies allow for new ways of being and knowing? And through these new modes of existence, how can worlding promote a state of community and becoming, foregrounding active solidarities?

The minor vocabularies of conspiracy theories, crypto, and other forms of secular magic trade in the promises of hermetic knowledge. Feelings of accessing another reality might rather be the effects of producing it by segregating those who are in from those who are out.

Contributors

Christian Ulrik Andersen, Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, is attempting to bring the knowledge and practices of digital culture and art to the fore.

Geoff Cox is Professor of Art and Computational Culture at London South Bank University, and co-director of Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (CSNI), working across software studies and contemporary aesthetics.

Camille Crichlow is a PhD Researcher at the Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Racism and Racialisation (University College London). Her research interrogates how the historical and socio-cultural narrative of race manifests in contemporary algorithmic technologies.

Mateus Domingos is an artist and MRes researcher at CSNI, London South Bank University.

From a network of Feminist Servers the following authors contributed: mara karagianni - artist, software developer, sysadmin, ooooo - Transuniversal constellation, nate wessalowski - PhD student at Münster University, vo ezn - sound && infrastructure artist.

Teodora Sinziana Fartan is an artist and PhD researcher at CSNI, London South Bank University.

Susanne Förster is a PhD candidate and research associate at the University of Siegen. Her work deals with imaginaries and infrastructures of conversational artificial agents.

Inte Gloerich (Utrecht University & Institute of Network Cultures) researches sociotechnical imaginaries around blockchain technology as they appear in for instance memes, startup culture, and art.

Daniel Chávez Heras is Lecturer in Digital Culture and Creative Computing at King's College London. He studies the computational production and analysis of visual culture.

Macon Holt is a a Post-Doctoral researcher at Copenhagen Business School. He is author of 'Pop Muisc and Hip Ennui. A Sonic Fiction of Capitalist Realism' (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Jung-Ah Kim is a PhD researcher in Screen Cultures and Curatorial Studies at Queen’s University. She studies the relationship between weaving and computing and traditional Korean textiles.

Edoardo Lomi is a PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School. His project focuses on the palliative care of digital infrastructures.

Inga Luchs is a PhD candidate at the University of Groningen. In her research, she deals with questions of data classification and discrimination from a cultural and technical perspective.

Gabriel Menotti is Associate Professor in Film & Media at Queen's University and an independent curator, and co-cordinates the Besides the Screen network.

Alasdair Milne is a PhD researcher with Serpentine Galleries’ Creative AI Lab and King’s College London. His work focuses on the collaborative systems that emerge around new technologies.

Anna Mladentseva is a PhD researcher at University College London whose project focuses on the conservation of software-based works of art and design from the Victoria & Albert museum.

Shusha Niederberger is a PhD researcher based at Zurich University of the Arts and working on user subject positions in datafied environments and aesthetic strategies of using otherwise.

Søren Bro Pold Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, works with the arts of the interface and interface criticism.

Roel Roscam Abbing is a PhD researcher in Interaction Design at Malmö University's School of Arts and Communication. There he studies alternative and federated social media systems.

Winnie Soon is a Hong Kong-born artist coder and researcher, engaging with themes such as Free and Open Source Culture, Coding Otherwise, artistic/technical manuals and digital censorship.

Magdalena Tyżlik-Carver ferments data and investigates Critical Data and related practices through curating. She is Associate Professor in Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University.

Varia is a space for developing collective approaches to everyday technology. https://varia.zone

Jack Wilson is a PhD researcher at the University of Warwick’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies. He is not a conspiracy theorist.

xenodata co-operative investigates image politics, algorithmic culture and technological conditions of knowledge production and governance through art and media practices. The collective is run by curator Yasemin Keskintepe and artist-researcher Alexandra (Sasha) Anikina.

Sandy Di Yu is a PhD researcher at the University of Sussex and co-managing editor of DiSCo Journal (www.discojournal.com), using digital artist critique to examine shifting experiences of time.

Freja Kir is researching across intersections of artistic methods, spatial publishing and digital media environments. Creatively directing fanfare – collective for visual communication. Contributing to stanza – studio for critical publishing. PhD researcher, University of West London.

Jack Wilson title

Jack Wilson text

Susanne Förster title

Susanne Förster text

Alasdair Milne title

Alasdair Milne text

Inga Luchs title

Inga Luchs text

Blockchains otherwise

Blockchains otherwise

Inte Gloerich

Is resistance to blockchain-based marketisation possible? Activist and artistic engagements with blockchain technology point to (at least) four different, partially overlapping, tactics towards this aim. The first is part of an accelerationist logic: riding the waves of capital until capitalism finally crashes, funding alternative values with whatever profit was accrued while it lasted. As Jaya Klara Brekke puts it: “tap the end of capitalism for those funds you will need in order to build new worlds” (2022, 104). The artwork Terra0 could be an example of this logic. Connecting a forest to a blockchain, the project gives the forest agency to sell its logs and buy more land to expand itself (Seidler, Hampshire, and Kolling 2016). Economic growth logic inverted for a more bountiful nature.

The second tactic is part of prefigurative politics, which David Graeber describes as “the idea that the organizational form that an activist group takes should embody the kind of society we wish to create” (2013, 23). Building alternative blockchain systems that perform a different kind of politics and social organization could be an example of this. DisCO, a distributed cooperative organisation inspired by feminist economics, thinks about ways of making visible the value of care work in blockchain-inspired governance systems. DisCo does not settle for blockchain ‘as is’, but bends it to fit their values (Troncoso and Utratel 2019).

Then, there are those that explore how blockchain’s logics can be subverted to make space – however minor – for different ways of relating in non-financialised ways. To explore what this might mean, I've been inspired by Patricia de Vries’ take on “plot work as an artistic praxis” (2022) that builds on decolonial theorist Sylvia Wynter’s description of plots: small, imperfect corners of relative self-determination within the larger context of colonial plantations (1971). De Vries asks how artistic work, implicated as it is in institutional and capitalist logics, can perform plot work to create space for relating outside of those logics. A possible answer to this question comes from artist Sarah Friend, who programmed her Lifeforms NFTs in such a way that they ‘die’ if they are not cared for. The NFT has to be given away for free to someone else, who then takes over the caring responsibilities (2021). Lifeforms represent little plots of care relationships, not only to the NFT, but also to those around you, calling on others to ‘care for’ instead of ‘capitalize on’.

However, these tactics hinge on the assumption that blockchain is here to stay. Perhaps another tactic should also be explored: how to protect fragile life-sustaining elements against capture by blockchain’s market logics? A tentative example could be Ben Grosser’s Tokenize This, that creates “unique digital objects” in the form of a url that is only accessible once, and is deleted straight afterwards (2021). This project doesn’t protect anything against tokenisation necessarily, but it does create slippery objects difficult to grasp through tokens. Perhaps ephemerality in the context of purported immutability can be a fruitful lens for more work in this direction.

Edoardo Lomi & Macon Holt title

Edoardo Lomi & Macon Holt text

nate wessalowski & Mara Karagianni (Feminist Servers) title

nate wessalowski & Mara Karagianni (Feminist Servers) text

Shusha Niederberger title

Shusha Niederberger text

Roel Roscam Abbing title

But does it scale?

Roel Roscam Abbing

This is a terrible question common in technical circles to judge the merit of proposals and projects: can your idea expand in size to be relevant to many and, therefore, relevant at all? It is also often used as a way to put down alternative proposals, based on the implication that these proposals won’t scale and are therefore not worth pursuing further. Simultaneously, scalability is one of Silicon Valley’s core concerns as it enables the massive profits of social platforms.

Initially, I found myself avoiding the question of scalability, but due to recent developments I find myself compelled to consider it sincerely. Alternative digital infrastructures can engender different social relations than those of the scaled social platforms. However, if we are to build other systems that “mirror the world we want to see” and build actual prefigurative counter-powers (Keyes et al.) to platform capitalism, these alternatives, in one way or another, will need to operate at scale.

The negative externalities of scaled social platforms are becoming ever more evident, leading to an interest for non-scalability or other undoings of scale. This is expressed in the grassroots of computational culture (de Valk), as well as within human-computer interaction research literature (Larsen-Ledet et al.; Lampinen et al.). Over scalability, this literature suggests other metaphors such as proliferation as a way to consider the impact of a project.

The concerns against scalability are manifold. Anna Tsing demonstrates how scalability is a system's property “to expand without changing the nature of what it does”(Tsing, 2012, p. 8) and, as such, is fundamental to extractive capitalism. Consequently, scalability has the effect of erasing difference and local diversity, leaving ruins in its wake.

In response to Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter in 2022, millions looked to Mastodon. This social network differentiates from Twitter in that it is a part of a network of thousands of smaller and interconnected sites known as the Fediverse, itself not run by any single entity. In the months after the purchase, this has proven to be a scalable system, but one that scales differently. Thousands of new and self-sovereign social networks were set up and through federation to become a part of a larger network. Thus, rather than scaling a single platform vertically, the process saw a network of networks scaling horizontally (Zulli et al.).

As someone who co-administers one of those small social networks, the months during Musk’s takeover made the necessity of scalability as a design property of software acutely felt. Our little space had to grow substantially within a short period of time. Not for growth or profit, but to be able to accommodate friends in need.

Through a different scalability, but scalability, nonetheless, millions managed to explore an alternative to the platform model by joining and trying, if only briefly, another model. Had the software and the model not been scalable at that moment of urgency, it would have been dismissed straight away. Instead, through scalability, the ideas and the model started to proliferate beyond the originary technical communities, after almost two decades of being around but being dismissed. Now that the terrible question is answered, we can start collectively posing more interesting ones.

xenodata co-operative title

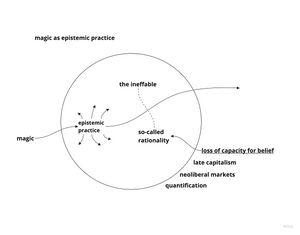

Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice

xenodata co-operative (Alexandra Anikina, Yasemin Keskintepe)

Speculative narratives of (techno)magic such as those offered by feminist technoscience, cyberwitches and techno-shamanism come from knowledge systems long marginalised in a hyper-optimised and hard-science-reliant capitalist discourse. Aiming to de-centre Western rational imaginaries of technology, they speak from alternative epistemic positions, decolonial and translocal perspectives. But what exactly does it mean to appeal to “magic” in the age of hegemonic Western epistemics? How do we deal with magic in the context of resistant tech practices?

Magic, as considered here, activates a different modality of the word “belief” than the commodified beliefs within capitalism. Rather, belief stands for a long-denied possibility of an alternative political imaginary (one that, as Mark Fisher suggests, is excluded within capitalist realism). Within this system, belief can only be exercised within the confines of certain institutions and framings: a church, a hospital, a rave, an art space. This is the core provocation of magic: it activates the systems of belief in spaces where they are not supposed to be activated.

Technology, in relation to magic, could also be liberated from being a despirited tool (a hammer), or from being a magic-wand type solution to the world’s problems; (techno)magic activates a reality-system of magic in certain space-times inside techno-capitalist infrastructures. At the same time, magic is not a universal solution to capitalism; it's not possible to exit into magic as some kind of an innocent primordial state. Magic is a granular, messy middle situated between sliding and not always matching scales of epistemic conditions, beliefs and politics.

(Techno)magic alters infrastructures, procedures and protocols, introducing the ineffable, 'that which cannot be captured by descriptive language, and which escapes all attempts to put it to "work"' (Campagna 10) - including not only human physical labour but also data put to work within statistical models. Yet, by animating the thought process, magic opens it to the possibility of the Other, and makes apparent the flows of (political) energy as an embodied experience. We understand (techno)magic as relational ethics + capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from libertarian, commodified, power-hungry, toxic, conquering forms of belief and knowledge; and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine.

Artists do this by means of rituals: Choy Ka Fai weaves (motion capture) technology within shamanistic dance rituals in his audio-visual performance Tragic Spirits, and Omsk Social Club creates Live Action Role Plays (LARP)that introduce communal “states that could potentially be fiction or a yet unlived reality” (Omsk). Both facilitate a bodily encounter with the reality-system of magic, a transgression into imaginary politics and other worlds.

We propose to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice. We appeal to a tentative future: thought becoming operationalised as we engage in thinking-with diagrams and use diagrams as rituals-demarcated-in-space; finding solidarity with our dead - ancestors, but also crude oil - in the face of the Anthropocene; rituals against forgetting; making technospirits and conjuring worlds.

Anna Mladentseva title

Anna Mladentseva text

Sandy Yu title

Feeling short on time? PhD Researcher claims it's because of digital optimisation

Sandy Di Yu

It’s me, I’m the researcher. And I’ve been running late for things all my life. I was born 10 days late, and then some decades later I was like, “why is everyone around me feeling like time has both stood still and disappeared?” It turns out there’s a load of people who have asked the same thing, people who are way smarter and more established, and those people have provided a myriad of interesting responses.

The most obvious answer to time scarcity lies in the hours of labour the average worker puts into her day. This is despite the fact that automation technologies have infiltrated every crevice of contemporary life (Crary, 2013: 40). The promise of emancipation from mundane work remains unfulfilled, mocking us as those same technologies produce ever more work or else commodify the small moments of respite in between.

The increase in work is a symptom of capitalistic growth, which necessitates accelerated productivity for its own survival. Yet since the use of digital platforms has become mainstream, the loss of time has reached a fever pitch. So the question then becomes, what is to be blamed for our current state of time scarcity: the managerial structure of our current socioeconomic system, or the development of digital technologies? Which came first and caused the other, the capitalist chicken or the technological egg?

While existing literature often points to both in equal measure, what is most striking is the inextricable ways in which digitality and management have become woven together in recent years. My hunch, thus, is that neither is solely culpable, for one wouldn't exist in its current form without the other. Instead, it is the logic of optimisation that enfolds both the systemic structure of digital technologies and the managerial framework of contemporary capitalism to cannibalistically exacerbate one another. Timescales thus become skewed such that time is paradoxically both negligible and infinite, due to processing speeds and the perceived perpetuity of digital media, respectively.

Optimisation might mean hiding the discrete units that necessitate digitality, making the metaphors of flow or stream into reality and predicated on the contrived synchronicity of micro-processes (Soon, 2016: 211). It could involve the trimming of code to fewer lines to achieve an aesthetic particular to “good” algorithms (Galloway, 2021:227). It could be following an unofficial but known set of rules in an attempt to get web pages in front of more viewers as with Search Engine Optimisation, or else squeezing every last drop of value from a data set (Halpern, 2022: 201).

Regardless of how it materialises, the logic of optimisation mirrors the mechanics of “progress”, a hangover from post-enlightenment sentiments that continues to plague the current state of socioeconomic affairs (Azoulay, 2019:21). Consequently, we are left with no future to work towards and no past for which to be liable, a perpetual present without time that we're somehow already late for.

Jung-Ah Kim title

What Weaving Can Teach Us

Jung-Ah Kim

Technology nowadays is characterized by a number of computer devices that we depend on, such as laptops, tablets, smartphones, smartwatches, etc. As the level of dependence that we have on these devices increases over time, it’s difficult to not think that we lose our agency over them. The black boxing of the devices, despite its merits, prevents us from connecting and understanding them even when they apparently exhibit ‘user-friendly’ interface designs.

Traditional crafts such as weaving may seem peripheral, and minor compared to advanced technology nowadays that entertain us and increase our productivity. However, hands-on engagement with old devices such as weaving handlooms could be pedagogical, shedding new light on our understanding of technology, offering an alternative relationship. I would like to share my experience of working on a weaving handloom that gave me new access to the technological things around me.

Weaving looms share a common history with computers. Many histories of computing begin with Analytical Engine, a calculating machine that Charles Babbage attempted to build in the nineteenth century. It is widely known that Babbage conceived this machine based on the punched card system and the formal mechanics of Jacquard’s loom, the first automated loom invented in 1804. The Jacquard loom used a long series of interconnected punched cards to encode more complex patterns while enhancing the production speed.

However, the connection between weaving and computers cannot be reduced to the role of punched cards. Weaving and computers naturally process data in similar ways regardless of the punched cards because to weave means to decide whether a warp thread is to be picked up or not. Therefore, weaving has been a binary art from its very beginning as stated by the computer pioneer Heinz Zemanek (Harlizius-Klück 179). A 4-shaft loom can be thought of as 4-bit opcodes with different orderings, resulting in indirect patterns (Griffiths, “Coding With Threads: Frame Loom”).

Working on a weaving loom can also inform us a lot about physical, tangible forms of interaction with technology. Spending hours manually setting up the loom, passing each thread into the heddles make you feel connected to the machine in an unexpected way. Your whole body interacting with the loom, throwing the shuttle across the warp, and controlling treadles to see your pattern emerge on the fabric gives you a sense of control that you’re working with the machine, not dependent on it.

This consequently offered me a new perspective and appreciation of the world full of handy and useful technical things that relate together and I’m part of, not separated from it or merely dependent on it. The smaller and older ways of engaging with traditional crafts and old devices made me feel empowered, rather than a minor being weighed down by big, complex tech knowledge. Many crafts and their technologies have a long history and as a result embody a great deal of knowledge and expertise. They invite you to the world of the common, average everyday experience of things full of surprises and wonder.

Freja Kir Kirchheiner title

Freja Kir Kirchheiner text

Mateus Domingos title

Mateus Domingos text

Gabriel Menotti title

Moving Textures

Gabriel Menotti

So-called poor media has a wealth of its own. TikTok choreographies and ASMR voiceovers win at the attention economy also because they achieve affective responses disproportionate to their modest (re)production requirements. There isn’t much to see, and it rarely matters what is being said. Through localized – and rather specific – stimuli, these and other kinds of oddly satisfying content overpower the available sensoria.

What could otherwise be taken as a formal deficit is at the core of this hypnotic potential. As a minor genre sitting at the fringes of commercial entertainment, oddly satisfying media seems to capitalize on the singular qualities of the textural. Textures, as once defined by Eve Segdwick, constitute “an array of perceptual data […] whose degree of organization hovers just below the level of shape or structure” (2003, 16). This structural insufficiency may lead to a short-circuiting of perception that supplies the feeling of physical properties not immediately present or represented. As one probably knows, particularly textural sights and sounds are often said to unfold through the sense of touch. Textures, in that regard, bear some sort of synesthetic density.

This large capacity for sensorial excitement makes textures instrumental for the aesthetic economy of digital media. As an actual component of digital assets, textures underpin hyperrealism and special effects alike, conveying high-fidelity sensation with little transmission of information.

The textural character of oddly satisfying media becomes evident in their propensity towards kinetic abstraction. Any meaning they may express is of little relevance and often interchangeable by any other. The logic under which they operate is above all phatic: more than signals to be decoded, oddly satisfying media propagates (like) frequencies to be vibed with. Transduction, rather than communication, is the name of this game. External references become subsumed under the pure concatenation of internal motion. By way of cognitive arrest and compulsion, moving textures integrate bodies into the otherwise incommensurable workings of media technologies, facilitating our couplings with the machine.

What follows feels like the surrender of agency. As consumption habits make one increasingly readable to the system, knowing subject and knowable object trade positions. Mesmerizing stimuli take the self out for a ride. Hi-octane fuel for late night doomscrolling: within the prosaic realities of social media, moving textures supplement the perverse incentives of the newsfeed. The latter infamously revolves like a slot machine, keeping us hooked with the deferred promise of a dopamine rush. The former, meanwhile, spins like secular praying wheels, inciting gleeful resignation.

Together, the newsfeed and moving textures seem to co-operate for the production of persistent network effects. An electronic babysitter for the disaffected of any age, playing its part in the disintegration of public spheres as it substitutes meaningful exchanges by a diffuse atmosphere of amorphous comfort - clogging the wires while transmuting people into views, likes, and subscribers.

Søren Bro Pold title

How to face face recognition?

Søren Bro Pold

Algorithmic profiling on platforms is used to create neighbourhoods of homophily (Chun). Corporate data-driven platforms serve to instrumentalize and capitalize on cognitive resonance (Drucker). This is almost impossible to avoid without simultaneously producing more data to be capitalized. A specific version of the profiling that is integrated into most platforms is the ways that gender recognition is used to censor images on Instagram. To make sure that Instagram is not used for sexual content, pictures with visible female nipples are erased, while male nipples are allowed.

As a continuation of trans activist Courtney Demone’s campaign #DoIHaveBoobsNow from 2015, the Copenhagen-based artist Ada Ada Ada has launched the In Transitu project. Each Thursday since December 2021 she has posted topless selfies of herself during gender transition as “a challenge to the Instagram moderation protocols” (Ada). Furthermore, she sends the images to commercially available gender recognition services. So far, Instagram has not blocked her selfies, though the other services often register her as female, however usually they disagree in their results.

The project demonstrates the discrimination caused by letting commercial services evaluate people into binary genders and controlling access via US moral ethics. As pointed out by Janus Rose: “If we allow these assumptions to be built into systems that control people’s access to things like healthcare, financial assistance or even bathrooms, the resulting technologies will gravely impact trans people’s ability to live in society” (Rose). The project demonstrates, and Ada Ada Ada reflects on, what it takes to be perceived as a specific gender: “The logic seems to be: Short hair = Male. Long hair = Female. Long hair on one side only = 50% Make/50% Female” (Ada).

Ada Ada Ada turns gender recognition into a public performance, which besides the discrimination points to the arbitrariness and absurdity of the gender recognition models and the binary and biased understanding of gender they build on, constructed through image sets. Consequently, they also point to the way gender is constructed in our culture(s). The project is a convincing demonstration that gender is not only biologically but culturally constructed.

In Transitu echoes a practice in the transgender community of posting pictures of bodily changes during gender transition as a way of showing mutual support. However, these images are in fact also captured to automatically ‘out’ transgender people by making gender recognition able to recognize transgender. Since it is still dangerous and even illegal to be transgender in many countries, this adds further risks of being targeted and persecuted.

In Transitu consequently demonstrates how we are all captured, modelled, and recognized by machine vision and profiling. As a performance, it uses this as a stage and to reflect on how we are all being staged. Ada Ada Ada puts herself in the spotlight, which is not without risk, but indeed a courageous act of transgender minor tech: Even if we are controlled by these binary structures, she will not let them define her gender.

Varia text title

Varia text

Magda Tyzlik-Carver title

Fermenting Data Journal - locations, bodies, good life

Magdalena Tyżlik-Carver

Jar is a broad-mouthed container, usually cylindrical and made of glass or earthenware.

I look at my jars of different shapes and sizes, made of glass. I use bigger ones to start the process of fermentation and smaller jars for storage of ferments, until I open them to eat.

My fermenting jars contain fermenting plant matter, usually variety of cabbages but also other vegetables and plants such as carrots, garlic, variety of onions, daikon radish, and ramson leaves. There are also various spices, seeds and roots: ginger, turmeric, fennel seeds, gochugaru powder. I add salt. Water comes from vegetables in krauts. If I have to take it from a tap, I boil it and wait to cool before adding to the jar to submerge the veg.

These fermenting jars are locations. Sites of life-sustaining chemical reactions that generate energy. You can watch how cabbages ferment. Salt insures that this is a non-hostile environment for good bacteria to proliferate. We can’t see these microscopic organisms with a naked eye, but we know they are there. In millions. I can smell the change they provoke. Soon enough it is possible to taste it too. Strong and sour; familiar odour hitting my nostrils briefly as I open the jar to release the gas. Later, I can smell its freshness too.

Once eaten, their work moves to my gut supporting my digestion, boosting bioavailability of nutrients, and my body’s healthy inflammatory response. What could be the good work that can be done while living the good life supported by microbes and fermentation?

Fermentation defines a metabolic process where under specific conditions (in this case no oxygen) microbes create energy, alcohol and lactic acid from sugar and starch. Some say that in its most basic fermentation is a controlled decay. Lyn Margulis and Dorion Sagan (1997), scientists and a researchers of microbial forms, defined fermentation as a microbial invention, ancient biotechnology, and an unprecedented feat that humanity has not matched. Together with photosynthesis, oxygen breathing and removal of nitrogen from the air, fermentation is a miniature chemical system, that has been part of the making of this planet.

Plant, minerals, microbes and I. We create patterns, in time, in bodies, in places. We inhabit each other while also being part of other configurations. At home, at work or school, on the street, in a jar, in the garden, in the city, on social media platforms. What are the patterns of good life there? What is the good work that is done there? Who does it and under what conditions? And for whom?

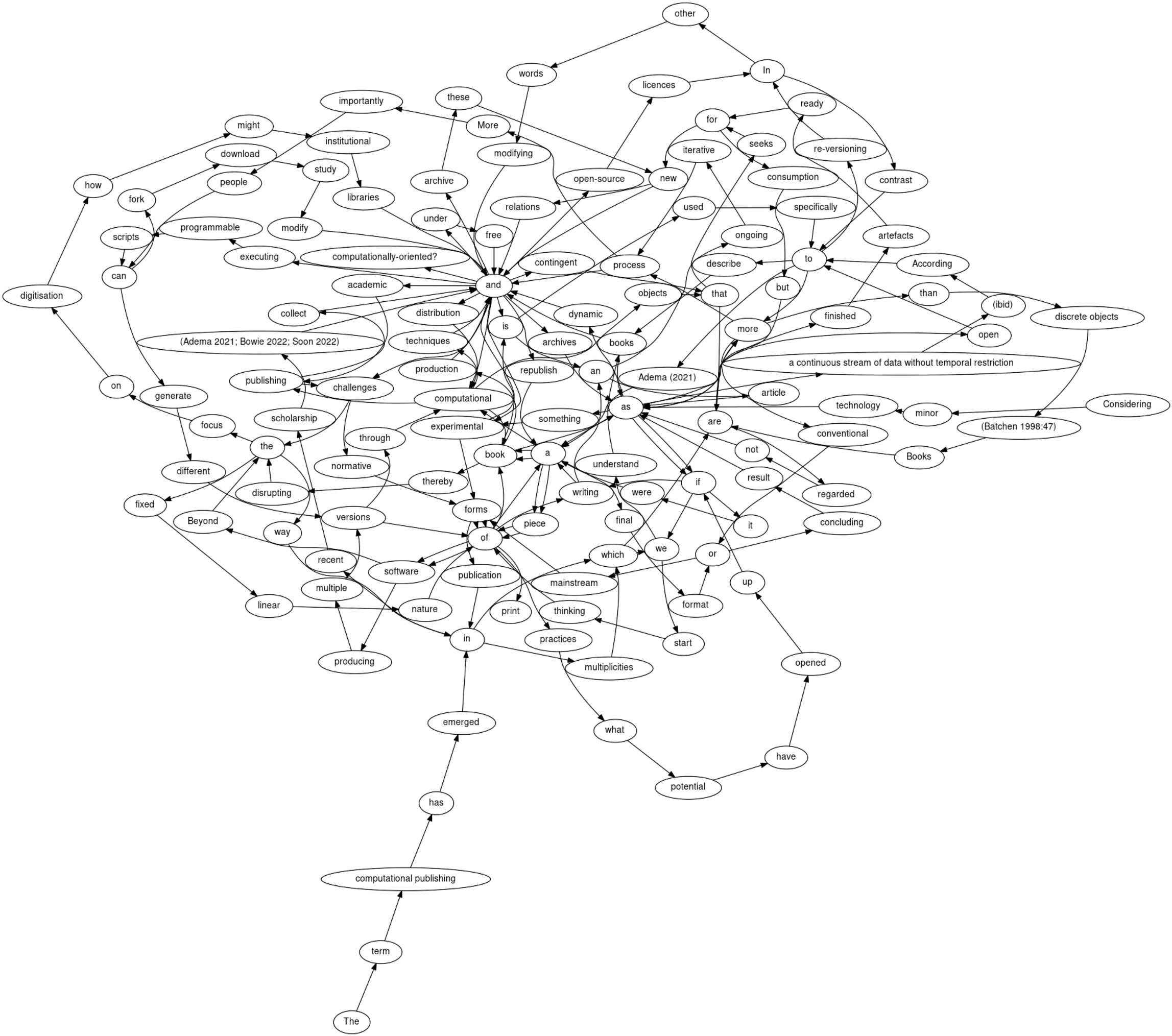

Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software

Writing an Article as if Writing a Piece of Software

Winnie Soon

To generate the graph on the left, execute the following code in the terminal with Graphviz installed : dot -Tsvg tm_article.dot -o tm_article.svg

tm_article.dot:

digraph G {

graph[overlap=false, splines = true];

node[fontname="Hershey-Noailles-help-me"]

layout=neato;

The->term->"'computational publishing'"->has->emerged->in->recent->scholarship->"(Adema 2021; Bowie 2022; Soon 2022)"->and->is->used->specifically->to->describe->books->as->dynamic->and->computational->objects->that->are->open->to->"re-versioning"->In->contrast->to->more->conventional->or->mainstream->forms->of->book->production->and->distribution->computational->publishing->challenges->the->way->in->which->we->understand->books->and->archives->as->more->than->"'discrete objects'"-> "(Batchen 1998:47)"->Books->are->regarded->not->as->a->final->format->or->concluding->result->as->finished->artefacts->ready->for->consumption->but->as->"'a continuous stream of data without temporal restriction'"->"(ibid)"->According->to->"Adema (2021)"->a->computational->book->is->an->ongoing->iterative->process->More->importantly->people->can->fork->download->study->modify->and->republish->a->book->as->if->it->were->a->piece->of->software->producing->multiple->versions->through->computational->techniques->and->under->free->and->"open-source"->licences->In->other->words->modifying->and->executing->programmable->scripts->can->generate->different->versions->of->a->book->thereby->disrupting->the->fixed->linear->nature->of->print

Considering->minor->technology->as->something->experimental->and->contingent->that->seeks->for->new->relations->and->challenges->normative->forms->of->practices->what->potential->have->opened->up->if->we->start->thinking->of->writing->an->article->as->if->writing->a->piece->of->software->Beyond->the->focus->on->digitisation->how->might->institutional->libraries->and->academic->publishing->collect->and->archive->these->new->and->experimental->forms->publication->in->multiplicities->which->are->more->process->and->"computationally-oriented?"

}

Bibliography

Colophon

A Peer-reviewed Newspaper

Volume 12, Issue 1, 2023.

Edited by all authors

Published by Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University

Organised in collaboration with Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, London South Bank University; King's College, London; transmediale, Berlin; Film & Media/FAS, Queen's University; and Varia, Rotterdam.

The publication was generated with wiki-to-print hosted on Creative Crowd, by Varia.

Publishing licence: CC4r - https://constantvzw.org/wefts/cc4r.en.html

Printing: Drukkerij Tripiti, Rotterdam. Printed in an edition of 2000 copies.

Design: Manetta Berends & Simon Browne (Varia) https://varia.zone

Fonts: All fonts used in this newspaper are published freely under the SIL Open Font License: https://scripts.sil.org/OFL, apart from Authentic Sans, which is published under the WTFPL: http://www.wtfpl.net/

- Authentic Sans

- Computer Modern

- Degheest Types

- Junicode Condensed

- Latitude

- Lucette

- Redaction

ISSN: 2245-7593 (Print)

ISSN: 2245-7607 (PDF)