APRJA Content Form - Editorial: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

'''Christian Ulrik Andersen & Geoff Cox ''' | '''Christian Ulrik Andersen<br>& Geoff Cox ''' | ||

= Editorial = | = Editorial = | ||

Revision as of 07:33, 15 October 2024

Christian Ulrik Andersen

& Geoff Cox

Editorial

Doing Content/Form

Content cannot be separated from the forms through which it is rendered. If our attachment to standardised forms and formats – served to us by big tech – limit the space for political possibility and collective action, then we ask what alternatives might be envisioned, including for research itself?[1] What does research do in the world, and how best to facilitate meaningful intervention with attention to content and form? Perhaps what is missing is a stronger account of the structures that render our research experiences, that serve to produce new imaginaries, new spatial and temporal forms?

Addressing these concerns, published articles are the outcome of a research workshop that preceded the 2024 edition of the transmediale festival, in Berlin.[2] Participants developed their own research questions and provided peer feedback to each other, and prepared articles for a newspaper publication distributed as part of the festival.[3] In addition to established conventions of research development, they also engaged with the social and technical conditions of potential new and sustainable research practices – the ways it is shared and reviewed, and the infrastructures through which it is enabled. The distributed and collaborative nature of this process is reflected in the combinations of people involved – not just participants but also facilitators, somewhat blurring the lines between the two. Significantly, the approach also builds on the work of others involved in the development of the tools and infrastructures, and the short entry by Manetta Berends and Simon Browne acknowledges previous iterations of 'wiki-to-print' and 'wiki2print', which has in turn been adapted as 'wiki4print'.[4]

Approaching the wiki as an environment for the production of collective thought encourages a type of writing that comes from the need to share and exchange ideas. An important principle here is to stress how technological and social forms come together and encourage reflection on organisational processes and social relations. As Stevphen Shukaitis and Joanna Figiel have put it in “Publishing to Find Comrades”: “The openness of open publishing is thus not to be found with the properties of digital tools and methods, whether new or otherwise, but in how those tools are taken up and utilized within various social milieus.”

Using MediaWiki software and web-to-print layout techniques, the experimental publication tool/platform wiki4print has been developed as part of a larger infrastructure for research and publishing called ‘ServPub’,[5] a feminist server and associated tools developed and facilitated collectively by grassroot tech collectives In-grid[6] and Systerserver.[7] It is a modest attempt to circumvent academic workflows and conflate traditional roles of writers, editors, designers, developers alongside the affordances of the technologies in use, allowing participants to think and work together in public. As such, our claim is that such an approach transgresses conventional boundaries of research institutions, like a university or an art school, and underscores how the infrastructures of research, too, are dependent on maintenance, care, trust, understanding, and co-learning.

These principles are apparent in the contribution of Denise Sumi who explores the pedagogical and political dimensions of two 'pirate' projects: an online shadow library that serves as an alternative to the ongoing commodification of academic research, and another that offers learning resources that address the crisis of care and its criminalisation under neoliberal policies. The phrase "technopolitical pedagogies" is used to advocate for the sharing of knowledge, and to use tools to provide access to information and restrictive intellectual property laws. Further examples of resistance to dominant media infrastructures are provided by Kendal Beynon, who charts the historical parallel between zine culture and DIY computational publishing practices, including the creation of personal homepages and feminist servers, as spaces for identity formation and community building. Similarly drawing a parallel, Bilyana Palankasova combines online practices of self-documentation and feminist art histories of media and performance to expand on the notion of "content value" through a process of innovation and intra-cultural exchange.

New forms of content creation are also examined by Edoardo Biscossi, who proposes "platform pragmatics" as a framework for understanding collective behaviour and forms of labour within media ecosystems. These examples of content production are further developed by others in the context of AI and large language models (LLMs). Luca Cacini characterises generative AI as an "autophagic organism", akin to the biological processes of self-consumption and self-optimization. Concepts such as “model collapse” and "shadow prompting" demonstrate the potential to reterritorialize social relations in the process of content creation and consumption. Also concerning LLMs, Pierre Depaz meticulously uncovers how word embeddings shape acceptable meanings in ways that resemble Foucault’s disciplinary apparatus and Deleuze’s notion of control societies, as such restricting the lexical possibilities of human-machine dialogic interaction. This delimitation can be also seen in the ways that electoral politics is now shaped, under the conditions of what Asker Bryld Staunæs and Maja Bak Herrie refer to as a "flat reality". They suggest "deep faking" leads to a new political morphology, where formal democracy is altered by synthetic simulation. Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias argues something similar can be seen in the mediatization of war, such as in the case of a YouTube video of a press conference held in Gaza, where evidence of atrocity co-exists with its simulated form. On the other hand, rather than seek to reject these all-consuming logics of truth or lies, Esther Rizo Casado points to artistic practices that accelerate the hallucinatory capacities of image-generating AI to question the inherent power dynamics of representation, in this case concerning gender classifications. Using a technique called "xeno-tuning", pre-trained models produce weird representations of corporealities and hegemonic identities, thus making them transformative and agential. Falsifications of representation become potentially corrective of historical misrepresentation.

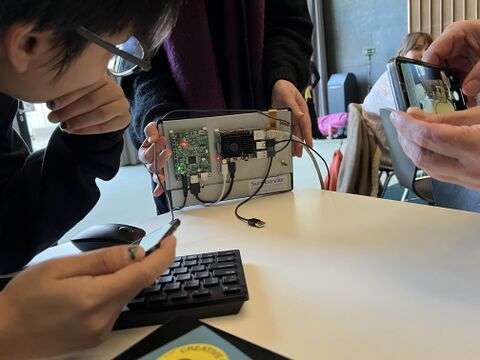

Returning to the workshop format, Mateus Domingos describes an experimental wi-fi network related to the feminist methodologies of ServPub. This last contribution exemplifies the approach of both the workshop and publication, drawing attention to how constituent parts are assembled and maintained through collective effort. This would not have been possible without the active participation of not only those mentioned to this point, the authors of articles but also the grassroots collectives who supported the infrastructure, and the wider network of participant-facilitators (which includes Rebecca Aston, Emilie Sin Yi Choi, Rachel Falconer, Mara Karagianni, Mariana Marangoni, Martyna Marciniak, Nora O' Murchú, ooooo, Duncan Paterson, Søren Pold, Anya Shchetvina, George Simms, Winnie Soon, Katie Tindle, and Pablo Velasco). In addition, we appreciate the institutional support of SHAPE Digital Citizenship and Digital Aesthetics Research Center at Aarhus University, the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image at London South Bank University, the Creative Computing Institute at University of the Arts, London, and transmediale festival for art and digital culture, Berlin. This extensive list of credits of human and nonhuman entities further underscores how form/content come together, allowing one to shape the other, and ultimately the content/form of this publication.

Notes

- ↑ With this in mind, the previous issue of APRJA used the term "minor tech", see https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

- ↑ Details of tranmediale 2024 can be found at https://transmediale.de/en/2024/sweetie. Articles are derived from short newspaper articles written during the workshop.

- ↑ The newspaper can be downloaded at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/File:Content-Form_A-Peer-Reviewed-Newspaper-Volume-13-Issue-1-2024.pdf

- ↑ See the article that follows for more details on this history, also available at https://cc.vvvvvvaria.org/wiki/Wiki-to-print.

- ↑ For more information on ServPub, see https://servpub.net/.

- ↑ In-grid, https://www.in-grid.io/

- ↑ Systerverver, https://systerserver.net/

Works cited

Andersen, Christian, and Geoff Cox, eds., A Peer Reviewed Journal About Minor Tech, Vol. 12, No. 1 (2023), https://aprja.net//issue/view/10332.

Shukaitis, Stevphen, and Joanna Figiel, "Publishing to Find Comrades: Constructions of Temporality and Solidarity in Autonomous Print Cultures," Lateral Vol. 8, No. 2 (2019), https://csalateral.org/issue/8-2/publishing-comrades-temporality-solidarity-autonomous-print-cultures-shukaitis-figiel/.

Biographies

Christian Ulrik Andersen is Associate Professor of Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University, and currently a Research Fellow at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies.

Geoff Cox is Professor of Art and Computational Culture at London South Bank University, Director of Digital & Data Research Centre, and co-Director of Centre for the Study of the Networked Image.