Content Form:APRJA 13 Bilyana Palankasova: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

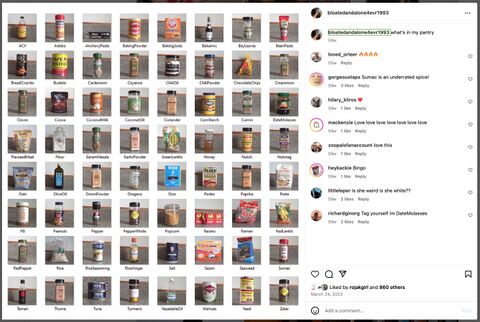

Consumerism fantasies, wealth, and wellness trends are recurring themes in Soda’s practice, which she also explores in works such as ''it just smells like literally like you're sitting on the beach drinking a margarita and you're loving your life and you're super rich and like you own a yacht'' (2020) and the subsequent ''My Candle Collection'' (2021), which use scented candles. The artist has reflected on these suggesting “sometimes I think my work is about shopping” (''Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda''). This statement could also be supported by the artist’s consistent engagement with and content about food-related household objects and places, like the kitchen, or the pantry (Fig. 5). ''What’s in my pantry'' (2023) suggests a parallel with the ‘What’s in My Bag’ trope in feminine lifestyle content, to reverse it and instead curate an alphabetical collection of ingredients and spices, found in the artist’s pantry. While we could read this through the lens of shopping, it is also another instance of the artist adopting archival behaviours – cataloguing, indexing, collecting, curating, presenting etc. This reading is evocative of the duality of the archive<ref>In this context and following Groys’s theory, ‘the archive’ is used interchangeably with ‘the museum.’</ref> and the supermarket, which Groys suggests in an interview, discussing ''On the New''. He describes the supermarket and the museum as the two models in our civilisation, extending a similar argument he does in ''On the New'', where ‘supermarket’ is framed as transient and focused on the now, whereas ‘the museum’ allows for comparison, because it preserves the old (Lijster, "The Future of the New: An Interview with Boris Groys"). In a sense, ''What’s in my pantry'' exemplifies this oscillation between the supermarket and the museum, or the profane and the archive. Content here emphasises the inclination and capacity of networked social platforms to imitate the archive by replicating its values – to save, collect, curate. Content crosses the value boundary between the two domains in the context of posting-as-practice and content-as-art, to point to the emergence of ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary digital practice. | Consumerism fantasies, wealth, and wellness trends are recurring themes in Soda’s practice, which she also explores in works such as ''it just smells like literally like you're sitting on the beach drinking a margarita and you're loving your life and you're super rich and like you own a yacht'' (2020) and the subsequent ''My Candle Collection'' (2021), which use scented candles. The artist has reflected on these suggesting “sometimes I think my work is about shopping” (''Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda''). This statement could also be supported by the artist’s consistent engagement with and content about food-related household objects and places, like the kitchen, or the pantry (Fig. 5). ''What’s in my pantry'' (2023) suggests a parallel with the ‘What’s in My Bag’ trope in feminine lifestyle content, to reverse it and instead curate an alphabetical collection of ingredients and spices, found in the artist’s pantry. While we could read this through the lens of shopping, it is also another instance of the artist adopting archival behaviours – cataloguing, indexing, collecting, curating, presenting etc. This reading is evocative of the duality of the archive<ref>In this context and following Groys’s theory, ‘the archive’ is used interchangeably with ‘the museum.’</ref> and the supermarket, which Groys suggests in an interview, discussing ''On the New''. He describes the supermarket and the museum as the two models in our civilisation, extending a similar argument he does in ''On the New'', where ‘supermarket’ is framed as transient and focused on the now, whereas ‘the museum’ allows for comparison, because it preserves the old (Lijster, "The Future of the New: An Interview with Boris Groys"). In a sense, ''What’s in my pantry'' exemplifies this oscillation between the supermarket and the museum, or the profane and the archive. Content here emphasises the inclination and capacity of networked social platforms to imitate the archive by replicating its values – to save, collect, curate. Content crosses the value boundary between the two domains in the context of posting-as-practice and content-as-art, to point to the emergence of ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary digital practice. | ||

[[File: | [[File:Bilyana Fig 5 Molly Soda.jpg|thumb|480px|Figure 5. Molly Soda, ''What’s in my pantry'' (2023), Instagram post, 24 March, 2023.]] | ||

Revision as of 12:25, 3 September 2024

Bilyana Palankasova

Between the Archive and the Feed

Feminist Digital Art Practices and the Emergence of Content Value

Abstract

This article discusses feminist performance and internet art practices of the 21st century through the lens of Boris Groys’s theory of innovation. It analyses works by Signe Pierce, Molly Soda, and Maya Man, to position practices of self-documentation online in exchange with feminist art histories of performance and electronic media. The text proposes that the discussed contemporary art practices fulfil the process of innovation detailed by Groys through a process of re-valuation of values via an exchange between the everyday, trivial, and heterogenous realm of social media (‘the profane’) and the valorised realm of cultural memory (‘the archive’). Using digital ethnography and contextual analysis, framed by the theory of innovation, the text introduced ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary art on the Internet. The article demonstrates how feminist internet art practices expand on cultural value through the realisation of a process of innovation via an intra-cultural exchange between the feed and the institution.

Introduction

This article considers feminist performance and internet art practices from the twenty-first century against Boris Groys’ theory of innovation, proposing that these practices fulfil the innovation process theorised by Groys through a re-valuation of values and intra-cultural exchange between online spaces (particularly social media), as profane, and the institution(s) of contemporary art, as the archive.

The article will discuss the practices of three multi-media artists who work with performance online, use self-documentation methods, and incorporate archival motifs in their work - Signe Pierce, Molly Soda, and Maya Man. Their practices will be framed as exemplifying artistic and cultural innovation following Groys’ conceptual framework of ‘the new’ by relying on intra-cultural exchange between feminist art histories and practices (the archive) and online content (the profane). The theoretical framework is applied to readings of the artworks constructed through digital ethnography.

Signe Pierce is a multi-media artist who uses her body, the camera, and the surrounding environments to produce performances, films, and digital images with a flashy, neon, LA-inspired ‘Instagram’ aesthetic. In her work she interrogates questions about gender, identity, sexuality, and reality in an increasingly digital world and identifies herself as a ‘Reality Artist’ ("Signe Pierce").

Moly Soda is a performance artist and a “girl on the internet” since early 2000s when as a teen she started blogging on Xanga and LiveJournal and in 2009 she started Molly Soda Tumblr (Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda). Her work explores the technological mediation of self-concept, contemporary feminism, cyberfeminism, mass media and popular social media culture.

Maya Man is an artist focused on contemporary identity culture on the Internet. Her websites, generative series, and installations examine dominant narratives around femininity, authenticity, and the performance of self online. In her practice, she mostly works with custom software and considers the computer screen as a space for intimacy and performance, examining the translation of selves from offline to online and vice versa.

Alongside a discussion of the documentary properties and archival themes in these digital practices, the article proposes content value as an artistic attribute, having emerged out of the exchange between the pervasiveness of networked technology (profane realm) and the established tradition of cultural archives.

Theory of Innovation

Innovation is a multifaceted term with different definitions and implications depending on discipline and context, whether it is cultural, artistic, scientific, or technological. Particularly throughout the twentieth, and especially in the twenty-first century, in a cultural context, innovation and the ‘new’ have been thought of as a method of resistance to the banality of commodity production (Lijster, The Future of the New: Artistic Innovation in Times of Social Acceleration 10). At the same time, with the accelerating pace of technology, innovation gained proximity to capitalist agendas and is overwhelmingly used to describe new products or services, often aligned with techno-solutionist approaches. Because of this prominence of technological innovation and its fundamental entanglement with capitalist production, innovation has become problematic in the context of contemporary art (11). In this context of inherent contradiction, can art still deliver social and cultural critique while being subjected to the steady pace of innovation? Philosopher of art Thijs Lijster identifies some of the more prominent aspects of innovation in relation to art and social critique: innovation’s capacity for critique, the distinctions between concepts and practices of innovation, the importance of innovation to artistic practice, and the capacity of innovation to be separated from acceleration (12). This article will consider innovation and the concept of the ‘new’ in its historical and institutional dimensions by using as an analytical framework Boris Groys’s theory of cultural innovation, which he developed in his book On the New. In line with this, the use of ‘innovation’ here refers to processes of cultural innovation which are interlinked with and produce processes of artistic innovation.

Overview of the Theory

In On the New, Groys suggests that contemporary culture is driven by the urge to innovate, and the process of innovation is closely entangled with the economic logic of culture. He claims that the idea of the new has changed and rather than meaning truth, utopia, or essence in cultural difference (which it did in modernist discourse), the new is defined by its positive and negative adaption to the traditional and established culture. Groys applies this principle to artworks in the sense that their value is determined by their relation to other artworks, or cultural archives, not to extra-cultural dimensions. At the same time, he suggests that there is a constantly shifting line of value between these cultural archives and the superfluous, profane realm of the everyday. Innovation occurs when an exchange is realised between the cultural archive and the profane. In this context, innovation means re-valuing what is already valued or established and cross-contaminating it with what is trivial, every day, and profane, so the new can emerge. Groys discusses his theory via examples from art, writing, and philosophy but the epitome of this process of innovation for him are Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades.

In this theoretical framework, I propose a reading of contemporary feminist internet practices as exemplifying the process of cultural innovation as described by Groys. The incorporation of content strategies into contemporary performance practice on the Internet is framed as a process of exchange and re-valuation of values between the established tradition of feminist practice and the vulgarity of contemporary networked social media. In this context, I propose ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary art, having emerged at the interface of critical creative practice, documentary performative practices online, and Web 2.0 social platforms.

The article is divided into three parts, each considering a segment of the theory of cultural innovation as developed by Groys to draw an analytical framework for thinking about artistic and cultural value at the intersection of art and content. The theory is presented in three subsequent parts, reflecting three key features of the process of innovation as described by Groys: "The Archive & The New", "The Value Boundary", and "Innovation as Re-evaluation of Values". Each theoretical part is paired with a discussion of the cultural and artistic conditions pertaining to the application of the theory to the subject of the article. In the first part, I discuss the cultural archives, or established art historical values, against which contemporary practices are valued. In the second part, I elaborate on how the value boundary is crossed by the use of content-as-document. In the third part, I suggest that ‘content value’ emerges as a feature of contemporary art in the last decade, as part of a process of cultural innovation based on exchange between institutionalised and valorized culture and networked social technologies.

The Archive & The New

On the New

On the New was first published in 1992 in German in the already mentioned context of increasing distrust towards innovation. Groys offers a theory which rejects the modernist implications of innovation, such as utopia, creativity, or authenticity, and instead positions innovation as a process of re-valuation of values. He wrote On the New against the debate of impossibility of new culture, theory, or politics and rather than supporting this impossibility for new culture to emerge, he positions the new as an outcome of the economic mechanisms of culture through a reinterpretation of older theories of innovation, to argue that the new is, in fact, inescapable. To understand or establish what the new might be, Groys stresses the importance of firstly dealing with the value of cultural works and where it comes from.

Groys posits that a work acquires value when it is modelled after a valuable cultural tradition - a process termed ‘positive adaptation.’ He opposes this process to the process of ‘negative adaptation’ – when a work is set in contrast to such traditional models (Groys 16). In this way, Groys positions cultural value as constructed by objects and practices’s relationship to tradition and established cultural and artistic norm; or their relationship to other objects and practices existing in certain cultural archives in a hierarchy of public institutions. These cultural archives are institutions such as libraries, museums, or universities, fulfilling a role of storing works in particular value hierarchy. In this context, the source of a cultural object’s value is always determined by its relationship to these archives: in the measure of “how successful its positive or negative adaptation is” (17). Or in other words, a cultural object’s value is based on its resonance or dissonance with ‘the archive’ where the use of archive stands for the institutional cultural spaces which collect, preserve, and disseminate cultural knowledge within an established hierarchy of values; the archive is the collective expression of institutionalised histories and practices in art and culture.

In this sense, Groys’s reading of the new and innovation is opposed to the modernist understanding of the new as utopian, true, or an extra cultural other[1] of the orienting mechanism of culture itself. This intra-cultural new is atemporal, it is not reliant on progress, it is grounded in the now and stands as much in opposition to the future, as it does to the past (41). According to him, the new is not an effect of original difference, is not the other, but emerges in a process of intra-cultural ‘revaluation of values’ - the new is always already a re-value, a re-interpretation, “a new contextualisation or decontextualization of cultural attitude or act” conforming to culture’s hidden economic laws (56–57). This new is achieved through the re-interpretation and re-contextualisation of existing values in a process of exchange between cultural domains. The revaluation of certain culturally archived values is the economic logic of a recurrent process of innovation.

To ground this in the article, I will discuss the cultural memory context, or the art historical background against which the works in questions are considered and valued. This part explains the relationship of the new to the cultural archives and elaborates the role of new technologies in a process of exchange with histories of feminist art.

Cultural Archives

The first part of Groys’s theory suggests that the source of a cultural object’s value is determined by its relationship to cultural archives and in the measure of how successful its positive or negative adaptation to these archives is. And through this adaptation and exchange, the process of re-valuation of values produces the new. In this section, I will establish the cultural archive, or art historical tradition, against which the practice of Pierce, Soda, and Man adapt to produce the new.

To determine what these practices’s relationships to established cultural and artistic norms are, we need to consider them against a tradition of practices existing in the cultural archives. Following Groys’s theory, the cultural value of ‘new’ feminist internet performance art is determined by its relationship to art historical context or lineage of similar work, in the measure of how successful the positive or negative adaptation to them is. The works of Pierce, Soda, and Man are underpinned by rich histories at the intersection of performance art, moving image, net art, and post-internet art dealing with gender, identity, and femininity.

The artistic traditions in question could be traced back to the 1970s, when Lynn Hershman Leeson started experimenting with fictional characters. Works like Roberta Breitmore (1973-1978) and Lorna (1979-1983) employed interaction and technology, such as TV and new video formats like LaserDisc, to critique the performance of gender (Harbison 70). Later, Hershman started making Internet-based projects, such as CyberRoberta (1996) (Harbison 71) to further examine the authenticity of self and the complications and anxiety emerging with the arrival of the Internet. Hershman’s The Electronic Diaries (1984-96) is a video series representative of a period in the 1980s and 1990s when artists were experimenting with cyberspace as a social space for self-representation and liberation (Harbison 7). In the videos, the artist confronts fears and traumas through recoded confessions, speaking directly to the camera. The tapes are fractured and use digital effects to reflect the psychological changes and misperceptions of self the protagonist experiences (Tromble 70). The series became a key work for the artist and for artists’ video more broadly as it restated and resonated with a lot of the feminist video themes of the preceding decade. At the same time, her work engaged with the new politics of representation that had emerged with the affordances of new communication and media technologies (Harbison 66).

Hershman’s contribution to what Rosalind Krauss at the time had termed ‘aesthetics of narcissism’ (Krauss) was suggesting that the separation of the subject and its fictional manifestations in the electronic mirror, need to be considered not just in the immediacy of the technological medium, but in the entire system and network of televisual environment (Tromble 145). Exploring early ideas around surveillance and confronting your image in real-time through new media, Hershman stresses the need for the mediated reflection to be understood not simply as a reflection of reality but as a force which actively manipulates and constructs reality. Thus, her work presents the screen as a space where identities are negotiated, constructed, and reconstructed. Through embedding the subject’s image within a larger television context, Hershman highlights the complexities of identity as mediated, fragmented, and entangled with fictional representations in the context of the pervasive influence of television.

Extending the thematic line of fictionalisation and trauma in another artistic context, mouchette.org (1996-ongoing) by Dutch artist Martine Neddam is an influential work of net art which takes the form of a personal website of a fictional character – a 13-year-old girl named Mouchette. The website takes the form of an interactive diary of a girl who shares thoughts on death, desire, and suicide. Neddam uses the characteristics of the web in ways which serve the story, such as confusing hyperlinks circulations, interactivity which layers the story, and constant identity play performed through a virtual character. The interactivity of the web and the nature of the work foster an active community of engaged audience which follows the work and could even use the website for their own projects (Dekker 152). Because of its expansive and pervasive character, the artwork has been a key case study in documenting and preserving net art since the project has generated documentation based on people’s experiences and memories, as well as documents of the site itself, making Mouchette a performative site and its own archive (Dekker and Giannachi 10). The interactivity and technological conditions of HTML also mean that the artwork facilitated these exchanges through anonymous interactions allowing the exploration of ambiguity and ethics in a way which today’s regulated online environments would impede.

Another key communication technology which was used in artistic performative experiments and became a transmitter of online female identities was the webcam. Ana Voog was the first artist to call her work ‘webcamming art,’ using her webcam as a tool to create Anacam (1997) – a twenty-four hours a day live broadcast of the artist’s home. Voog streamed daily activities, such as cooking, cleaning, having sex, chatting with cam-watchers, and hosting visitors. Alongside her vernacular, domestic activities, Voog also included performance art and visual experiments (Lehner 119). Blending performance and authenticity, Voog was one of the first artists to engage in continuous webcam streams and interacting directly with her audiences. Her use of technologies like a webcam and the Internet created art which was personal and had a new kind of immediacy for the audience.

A decade later, Petra Cortright took a different approach to webcam art with VVEBCAM (2007). The artis recorded herself staring into her webcam while playing with the various visual effects of her 20 USD webcam, including overlays of animated pizza slices, cats, and snowflakes (Lehner 120). The video was uploaded on YouTube and marked a significant departure from the typical camgirl genre where rather than addressing the camera and audience directly and engaging with erotic themes, Cortright documented herself as an immersed user, interacting with her computer ("Net Art Anthology"). In the video, Cortright appears to not wear makeup and is dressed casually, seemingly purposefully ‘unsexy’ (Lehner 120). When the video was uploaded to YouTube, she added tags, which rank higher in search engines and attract users looking for explicit content, like “tits vagina sex nude boobs britney spears paris hilton” (Soulellis 428). VVEBCAM took place on the cusp on a massive transformation in the way online users engage with posts, as soon after, the feed emerged – Facebook’s newsfeed ‘The Wall’ was introduced in 2006 and the iPhone was launched in 2007 (Soulellis 428). At the same time, artists started experimenting with posting on surf clubs and other blogs as a method to draw attention to the artistic value of user content (Moss 149).

Posting originally evolved into a metaphor for an online condition in the early days of the Internet but especially with the expansion of networked activity in the 1980s, and was a term which transitioned from newspaper bulletin boards and drew on wider traditions of announcement by and within a community (Soulellis 425–26). Relatedly, the origins of ‘content’ can also be traced to publishing metaphors and related to the visual or textual material in books, magazines, and newspapers. At the turn of the century, open and participatory web and digital media tools, like blogging, and particularly in 2005 with the launch of YouTube, brough fundamental changes in the media and information environment, in the way that audiences responded to culture online (Burgess 60).

In this context, another key moment for creating performance and video art for the new Web 2.0 platforms was Ann Hirsch’s The Scandalishious Project (2008-2009). For eighteen months, Hirsch’s fictional character Caroline Benton, a self-described camwhore, hipster, and freshman college art student in upstate New York, uploaded over a hundred monologic, blurry, low-resolution webcam videos to her YouTube channel Scandalishious (Steinberg 47). In the series, the artist danced in front of her webcam, vlogged, and engaged with followers, which responded to and commented on the videos ("Net Art Anthology"). The videos are satirical and humorous and play on stereotypes about sexiness and heterosexual desire (Brodsky 91–104). Scandalishious is a very early example of social media-based work and in the performance, Hirsch addresses the subject of girls online via an exploration of self-representation as feminist practice ("Net Art Anthology").

The artworks discussed here inform the context in which Pierce, Soda, and Man work and form the cultural archives against which the practices of the three artists are valued. They represent a lineage of works using performative and documentary strategies (similar to previous generation of feminist practice) and new technology – such as TV, LaserDisc, HTML, webcams etc. This illustrates a trajectory of feminist performance artists engaging with multimedia technologies, Web 1.0, and later Web 2.0. The arrival of Internet platforms for text and visual media, such as blogs, surf clubs, and later YouTube and others introduced online posting as an artistic method which also drew on the community fostering aspects of the digital platforms. Concerned with girlhood, femininity, hyperreality, cyberfeminism and subjectivity of identity, these artworks and practices use technology and documentary strategies to perform, curate, collect and archive selves via new media and digital technologies. The work of Pierce, Soda, and Man positively adapts to the cultural archive and steps on these histories and traditions to perform a process of innovation where new practices emerge through revisiting the established critical value of the art historical examples. At the same time, it negatively adapts to the archives by engaging them in a process of exchange with the vulgarity of contemporary networked social media.

This is not to say that the argument of the text is that the contemporary works are innovative compared to their art historical predecessors in a way which detracts from tradition. Rather, following Groys, innovation here is regarded as an ever-repeating cultural process which ultimately adjusts established cultural values to repeatedly incorporate the transitory everyday, to produce cultural and artistic newness. The practices of Pierce, Soda, and Man are interrogated as representative of the period 2014 – 2024 when the ubiquity of networked communication technologies and user-generated content (along with the existing traditions of feminist performance using technology described above) produce the conditions for the emergence of ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary art.

Value Boundary

On the New

Foundational principle of how cultural archives function is that they embrace the new and reject the derivative - what’s new is understood as different, while also being as valuable as the old. At the same time, “organised cultural memory rejects as superfluous and redundant everything that merely reproduces what already exists” - Groys identifies this domain which comprises all things that are not included in the archives, as ‘the profane realm’ (64). He suggests that there is a constantly shifting line of value that separates ‘the archives’ from ‘the profane realm,’ where ‘profane’ consists of that which is perceived to be valueless, extra-cultural, and transitory. Within this conceptual framework, something becomes new when it moves from the profane realm to the archives, as the profane, by virtue of its heterogeneity, becomes “a reservoir for potentially new cultural values” (64). The proposition of this article is that content (or user-generated content), as a dimension of artistic work, has realised this move from the profane realm of pervasive social media to the archives (or to institutionalised culture).

To ground his theory, Groys uses Duchamp’s ready-mades as an example and discusses his work L.H.O.O.G (1919) as well as The Fountain (1917) to compare profane things with cultural values. In 1919, Duchamp drew a moustache and a goatee on a postcard depicting Mona Lisa. The title is a sort of word play and eliding the words in French sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul,” or “There is fire down bellow” (Duchamp). Duchamp’s interpretation of Mona Lisa is a “mutilated reproduction, which is basically a piece of trash” (65) and by confronting da Vinci’s work with its derivative, Duchamp exposes them as two different visual forms, suggesting there is no essential criteria to distinguish them based on their value. And if the “piece of trash” is as beautiful as the Mona Lisa, then [we should] “consider every hierarchising value distinction between the two images to be an ideological fiction designed to justify the domination of certain institutions of cultural power” (66). The newness in this comparison emerges in the act of value juxtaposition of two things which are usually assigned different values. The comparison does not eradicate the value hierarchy but means that “the trashy reproduction, regarded as a new object, gains access to the system for the preservation of culture” (66). As a result of the comparison, the reproduction is valorised and gains cultural value, since it presents itself as the other, or the profane, while at the same time due to a certain critical analysis, is also similar to existing cultural values. This valorisation, however, does not affect the fundamental distinction between the archive and the profane; the fact that a comparison’s been made across the value boundary doesn’t eradicate the boundary, it just modifies it (66).

To ground this part of the theory, in the next section I consider networked social platforms as the profane to discuss the shifting line of value between the archive and the profane in the works of Signe Pierce and Molly Soda.

Content crosses the value boundary

Performative practices on the Internet, and particularly on social networking platforms, are simultaneously performance, documentation, and content. Content aesthetics and behaviours become a feature of such online practices by occupying an artistic, documentary, and public social space. Between the archive and the feed, the content characteristics of these practices cross the value boundary between the valorised and the profane, often via photographic documentation. With the novelty of networked social technologies long gone, subscribing to the behaviours and politics of the feed is the epitome of the everyday, transitory, heterogenous, profane realm of contemporary life. If Hirsch and Cortright posted on YouTube as a practice of experimenting with new networked technologies, a decade or so later social media is fully integrated into online performative practice. At the same time, posting as part of practice borrows qualities and behaviours from the archive itself, such as indexing, tagging, collecting, preserving, and curating. Through these behaviours and conditions, content as part of art, shifts the value boundary between the archive and the profane.

While there are examples of early artistic engagement with social media, some of which were discussed in the previous chapter, the foundational artwork for performative practice on social media is Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections (2014). Ulman performed a fictional makeover on Facebook and Instagram, in which for several months, she did a scripted online performance. Using her social media profiles, Ulman performed various makeovers and lifestyle fantasies, including a breast augmentation, strict Zao Dha Diet, and regular pole-dancing lessons. Packaged in the form of content, the artist used various sets, props, and locations to critique consumerist fantasies by succumbing to what social media demanded of her to be – a ‘hot babe’ ("First Look"). Excellences & Perfections is the work indicative of the start of the period in question in this text and a prime example of Groys’s theory in the way it introduces content aesthetics into a critical artistic context.

Signe Pierce particularly draws on content and Instagram aesthetics and dynamics in her work to reflect on the immediacy and consumption associated with social media content, as well as the urge to capture, record, and document. Two examples are When You Die, Your Camera Roll Flashes before Your Eyes (2019) – an expedited infinite scroll-through of the artist’s iPhone photo library and Digital Streams of an Uploadable Consciousness: Stories 2016-2019 - a 20-minute-long amalgamation of the artist’s Instagram stories and Snapchats from the three-year period. Pierce describes these works as “things that I’ve uploaded to the Internet to be consumed by people” (Bucknell and Pierce). They are not chronological, nor cohesive and constitute a live growing archive – the artist was interested in building an archive of digital streams that quantifies her reality as a purging process in which she exports herself before reaching the next stage of her work (Bucknell and Pierce). The work emphasises the transient nature of digital content while at the same time it is highlighting the impact of these digital narratives on self-representation. Through the documentation and archiving of ephemeral Instagram stories, Pierce suggests that content accrues value over time as part of a digital archive. The works are a heterogenous stream of self-documentation consisting of purely aesthetic or representation content alongside critique of techno-capitalism and data rights violations. Both these works reflect Pierce’s examination of “art world hierarchies and the currency of digital content” (Signe Pierce). Content is both the subject and the method of the work - the framing of digital content as currency lends itself useful in thinking about content as crossing a value boundary and being elevated to art status. Pierce frames everyday digital artefacts like Instagram stories and camera roll images as significant cultural objects, blurring the line between the archive and the profane.

Through her interest in art world hierarchies, Pierce reflects on the exclusivity and inaccessibility of the art world and the capacity for the Internet and social media to reach beyond the art world. This is particularly evident through one of her most accomplished works - American Reflexxx (2015). An unscripted video footage in collaboration with director Alli Coates, in the short film the artist is walking down Myrtle Beach Boardwalk wearing a mirrored mask and an electric blue mini-dress. It was uploaded on YouTube in 2015 and immediately went viral reaching over 2 million views in its first week. The project represented a filming of “the cyborg walking around” and while Pierce walks down the Boardwalk performing, she gets subjected to various forms of mistreatment, ridicule, and abuse, which the authors did not anticipate. One passer-by shouts “It’s just pretentious performance art” (Fig. 1) and in an interview for Mousse Magazine, the artists shares this was the only instance for the hour-long duration of the performance that somebody mentioned art (Bucknell and Pierce). At the same time, people could constantly be seen filming her and one is heard saying, “I’m putting this on Instagram” (Fig. 2). In juxtaposing these two perceptions by Pierce’s audience – one of pretentious performance art, and one of content worthy of virality – we could conceptualise of the shifting line of value between those two domains.

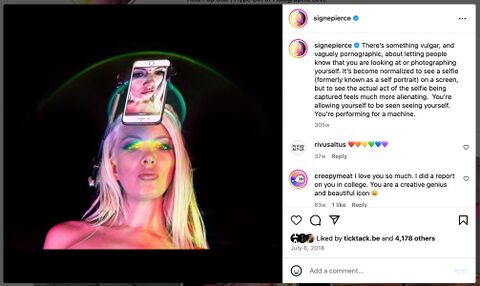

Instagram aesthetics and social medial logics underpin Pierce’s wider practice and become a critical dimension of her ‘Reality Artist’ persona. Alongside conceptual works, Pierce also creates hyper-saturated photographs of Los Angeles palms and neon strip malls which have a distinct visual language drawing on hyperreality, LA aesthetics, and ‘trash culture’ and evocative of vaporwave with its play on consumption, nostalgia and self-referentiality. For instance, in an Instagram post from 2018, the artist shares a cyborgian image of herself taking a selfie with a selfie stick and surrounded by a green light halo. In the caption, she dwells on the vulgarity of being perceived photographing yourself and the alienation of performing for the machine (Fig. 3). Adoring fans have filled the comment section with pledges of love and appreciation of the artist’s creative genius not unlike a celebrity fan club. Content is key feature of the artist’s aesthetic and posting has become part of practice, blurring the line between production, presentation, distribution, and consumption. Networked media has introduced new mechanisms of production and spectatorship, and new forms of value. This is not a condition which compromises the validity of the aesthetic experience provided by the museum, but one which states the contribution of networked platforms to processes of cultural value. The established cultural values of femininity, performance and hyperreality at the critical junction of documentation and digital distribution, are taken out of the institutional archive and into the profane realm of the transitory feed. Here, the documentary, and particularly self-documentation, become the vehicle for the shifting line of value between the archive and the feed.

Molly Soda’s practice includes video performances, social media posts and gallery installations and her work exists on platforms such as Tumblr, YouTube, and Instagram. In her work, she documents and explores processes of constructing, surveilling, and documenting herself. Over time, she became increasingly fascinated with how people construct and perform identities online as part of an evolving culture of trends, codes, and communities with their own vernacular. The artist performs herself as a character within the space of her home and her bedroom has become a widely recognised iconic space on the Internet. Through Soda’s perspective, the Internet is an aspirational space and an embrace of the multiplicities of character you could explore through it, especially in the very millennial way of being confessional online and the self-consciousness and anticipation of other people’s perception of you (Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda).

Me Singing Stay by Rihanna (2018) is a key work, which came out of the artist’s love for girls singing alone in their rooms. The artist was obsessed with the song ‘Stay’ by Rihanna and started compiling a playlist of YouTube videos of girls singing it. Eventually, the artist created a choir of 42 videos with a recording of herself in the centre, also singing the song (Soda). In her work, Soda extensively draws on documentary methods, in line with artist previously discussed in the article. Here, she expands and reverses the documentary space of performance by inserting herself in a collection of digital artefacts. Drawing on the Internet’s culture of vulnerability and immediacy, the artist grounds the work in intimate, emotional, bedroom performances, by curating a collection of digital artefacts out of the heterogenous chaos of the platform. This way, the work positively adapts to a tradition of self-documentation and technological intimacy, while also negatively adapting to such tradition by challenging the hierarchies of cultural archives through appropriating their methods. The line of value between the archive and the profane, or the artwork and content, is also challenged and set in motion by the archival behaviours of collecting and curating, performed by the artist in a transient online space. These methods of collecting content could also be observed in the work Me and my Gurls (2018) consisting of the artist dancing alongside animated GIF gurls joining her in the video, each trying to look sexier than the previous one. Performative artistic practices online are often underpinned by the creation of self-images which are framed as empowering and have become a sort of vernacular photographic practice which embraces “conventions of posturing the self to rehearse certain cultural stereotypes” (Proulx 115). Soda “overidentifies” with the image of the self-empowered, hyper-feminine bedroom camgirl” and through selfies, GIF blog posts, glittery and pink clichéd camgirl imagery depicts a subversive feminine image of unshaven and menstruating body (Proulx 115–16). In a sense, she critiques the mainstream media representations of women by propagating subversive images in the everyday realm where they thrive the most – on social media. This section discussed examples from Pierce and Soda’s practices to illustrate the ways in which the value boundary between art and content shifts through the artists’ use of documentary, archival, collection and curation methods. Applying these approaches to the heterogenous nature of online platforms, they realise a mobility of values in exchange between cultural tradition and Internet vernacular, which produce the conditions for the emergence of ‘content value’ as a key feature of artwork produced on the Internet.

Innovation as Re-valuation of Values

On the New

Crucially, Groys theorises of innovation as an exchange – the hierarchy of values held by the archive is reorganised by a cultural-economic form of exchange “between the profane realm and the valorised cultural memory” (139). In this context of both subscribing to and challenging institutionalised cultural value, Groys suggests that cultural innovation is a process realised by a strategic synthesis of positive and negative adaptation to the valorised cultural tradition because the new still exists and defines itself against the old (107–08). The result of this process is that things in the profane realm become valorised and enter the cultural archive, while other cultural works are devalorized and enter the profane realm. Importantly, this is not to say that if this process of innovation devalorizes certain cultural values, it also detracts from them – to reference the previously discussed example, da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is just as admired after Duchamp, as it was before (Groys 73).

Here, innovation constitutes an egalitarian gesture establishing an equalising moment between the valorised culture (or the archive) and the profane realm. However, valorised culture inherently assigns importance to this gesture and as a valorised realm, it is only seemingly criticized by it. Instead, every such process of innovation fulfils the cultural-economic mechanism and contributes to the expansion of both valorised cultural memory and the hierarchy of institutions which ensure its functioning. In a sense, this innovation process reinforces and maintains the power of the established cultural archive, as it is always grounded in the re-valuation of values, recalibrating. Because of this, it is futile to try an answer a question about the meaning of innovation, as this is a question about innovation’s relationship to extra-cultural reality. What’s relevant to culture is not the meaning of innovation, but the value which drives the process of innovation. Or in Groys’ words, “For culture as a whole, in any event, all that matters in each individual instance is that the value boundary separating cultural memory from the profane realm was successfully crossed and that an innovation occurred as a result” (Groys 74–75).

The Content Value of Art

In this theoretical context and innovation framework, the final part of this article extends further the proposal of ‘content value’ as underpinning the exchange between the archive and the profane. Building on the examples from the cultural archive, and the contemporary works discussed, the article considers other examples of Soda’s work alongside the work of Maya Man as an example of the emancipation of content-as-art from the documentary.

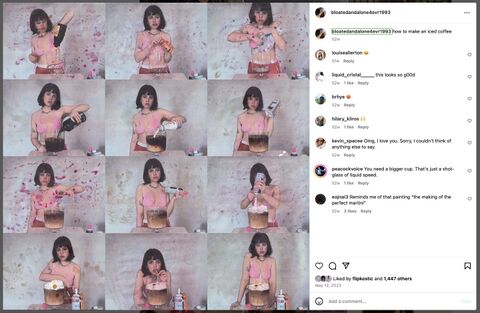

making an iced coffee (2023) is a YouTube video performance of Soda preparing a huge iced coffee using large amounts of incredients, incluidng syrup, milk, variou creams, and candied cherries, while wearing a pink bikini top. The silent deadpan video immediately invokes Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) and in a similar way subverts common stereotypes and perception of women, particularly via the trope of cooking videos and TV housewifes. The work could be interpreted as positively adapting to the cultural archive via the comparison to Rosler, while it negatively adapts to it via its presentation as content. Alongside its video form on YouTube, the work also exists as 12 stills grid image on Instagram (Fig. 4). Through excess and indulgance, the work suggests consumerist fantasies with the artist at the centre, drawing on the trope of the hot girl online. Satirising the ubiquity of ‘how-to’ videos, the work simultaneously critiques the commodification of femininity and the proliferation of content.

Consumerism fantasies, wealth, and wellness trends are recurring themes in Soda’s practice, which she also explores in works such as it just smells like literally like you're sitting on the beach drinking a margarita and you're loving your life and you're super rich and like you own a yacht (2020) and the subsequent My Candle Collection (2021), which use scented candles. The artist has reflected on these suggesting “sometimes I think my work is about shopping” (Virtual Studio Visit: Molly Soda). This statement could also be supported by the artist’s consistent engagement with and content about food-related household objects and places, like the kitchen, or the pantry (Fig. 5). What’s in my pantry (2023) suggests a parallel with the ‘What’s in My Bag’ trope in feminine lifestyle content, to reverse it and instead curate an alphabetical collection of ingredients and spices, found in the artist’s pantry. While we could read this through the lens of shopping, it is also another instance of the artist adopting archival behaviours – cataloguing, indexing, collecting, curating, presenting etc. This reading is evocative of the duality of the archive[2] and the supermarket, which Groys suggests in an interview, discussing On the New. He describes the supermarket and the museum as the two models in our civilisation, extending a similar argument he does in On the New, where ‘supermarket’ is framed as transient and focused on the now, whereas ‘the museum’ allows for comparison, because it preserves the old (Lijster, "The Future of the New: An Interview with Boris Groys"). In a sense, What’s in my pantry exemplifies this oscillation between the supermarket and the museum, or the profane and the archive. Content here emphasises the inclination and capacity of networked social platforms to imitate the archive by replicating its values – to save, collect, curate. Content crosses the value boundary between the two domains in the context of posting-as-practice and content-as-art, to point to the emergence of ‘content value’ as a feature of contemporary digital practice.

Notes

- ↑ The concept of the new as an extra-cultural other is closely tied to modernist understandings of artistic innovation as occurring in opposition to and outside of established cultural norms. For example, this could be traced back to the 20th century avant-garde positioning itself against the mainstream cultural order, or later to the work of The Frankfurt School, particularly Adorno and Horkheimer, arguing that true innovation exists outside the realm of the commodified cultural product.

- ↑ In this context and following Groys’s theory, ‘the archive’ is used interchangeably with ‘the museum.’