Toward a Minor Tech:Wilson5000: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (→QAgg) |

||

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

Given that QAgg’s archive contains a wealth of additional materials (Twitter, Gab, and TRUTH Social posts from several figures who have–in one way or another–become incorporated into QAnon’s worldview), the act of mapping Q Drops onto the external materials and events in the world is effectively automated by way of the various means of corpus-building within its interface. In essence, the affordances of QAgg represent the methodological ''avant-garde'' of QAnon ‘research,’ wherein every thinkable mechanism for the extraction of meaning, bringing into relation, and ultimate production of ‘research’ findings have been operationalised upon its materials–and if these affordances are not sufficient than a user can go to QAgg’s ‘Data Science’ tab and download JSONs or CSVs of QAgg’s archives and perform whatever further analysis upon these materials they wish. Although QAgg’s preoccupation with metadata speaks to a certain effort towards the appropriation of data science’s methods in the aggregator, the provision of these files warrants further reflection. Specifically, because it represents an attempt to utilise technical apparatus of neoliberal governmentality and epistemology (Chun) – aspects of the QAnon subject’s alleged ‘oppressors’ – towards furthering the epistemic basis of the phenomenon’s fascist worldview.<ref>See also Lee et al. on Covid-19 sceptics’ use of analogous rhetoric and methods towards similarly reactionary aims.</ref> | Given that QAgg’s archive contains a wealth of additional materials (Twitter, Gab, and TRUTH Social posts from several figures who have–in one way or another–become incorporated into QAnon’s worldview), the act of mapping Q Drops onto the external materials and events in the world is effectively automated by way of the various means of corpus-building within its interface. In essence, the affordances of QAgg represent the methodological ''avant-garde'' of QAnon ‘research,’ wherein every thinkable mechanism for the extraction of meaning, bringing into relation, and ultimate production of ‘research’ findings have been operationalised upon its materials–and if these affordances are not sufficient than a user can go to QAgg’s ‘Data Science’ tab and download JSONs or CSVs of QAgg’s archives and perform whatever further analysis upon these materials they wish. Although QAgg’s preoccupation with metadata speaks to a certain effort towards the appropriation of data science’s methods in the aggregator, the provision of these files warrants further reflection. Specifically, because it represents an attempt to utilise technical apparatus of neoliberal governmentality and epistemology (Chun) – aspects of the QAnon subject’s alleged ‘oppressors’ – towards furthering the epistemic basis of the phenomenon’s fascist worldview.<ref>See also Lee et al. on Covid-19 sceptics’ use of analogous rhetoric and methods towards similarly reactionary aims.</ref> | ||

While | While the actual content of QAgg’s materials is effectively secondary to their metadata, QAgg nevertheless offers several means through which users can share Q Drops to other platforms and, therefore, facilitate the dissemination of their ‘research.’ This includes means to generate a direct link to a given Q drop, copy its text, or generate a jpeg image of it as it appears on QAgg. The most interesting distribution tool, however, is ‘digital camo.’ This affordance produces a randomly generated dazzle camouflage pattern underneath the content of a Q Drop in an effort to evade image recognition-based moderation systems and therefore–in theory–allow for the circulation of Q drops on platforms where QAnon has been banned (Facebook, Google, Twitter, see also fig. 10). Whether or not such mechanisms of evasion work, such anticipation of machinic moderation speaks to questions of QAnon’s potential to develop minor tech in the recognition and subversion of platform governance strategies. It also speaks to particular mechanisms of subject formation within QAnon where the stigmatisation of this material serves to reify it as – essentially – ‘what they don’t want you to see’ (see Barkun). That the effort to subvert this marginalisation takes the form of a camouflage is also instructive as it speaks to the militaristic ontology of the QAnon subject; they are not just ‘researchers,’ but “digital soldiers” (Roose) in an insurgency. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|[[File:QAgg Digital Camo 1.png|200px]] | |[[File:QAgg Digital Camo 1.png|200px]] | ||

Revision as of 09:11, 11 August 2023

Jack Wilson

Minor Tech and Counter-revolution:

Tactics, Infrastructures, QAnon

Minor Tech and Counter-revolution: Tactics, Infrastructures, QAnon

Abstract

Following repeated assertions by QAnon promoters that to understand the phenomenon one must ‘do your own research’ this article seeks to unpack how ‘research’ is understood within QAnon, and how this understanding is operationalised in the production of particular tools. Drawing on exemplar literature internal to the phenomenon, it examines discourses on question of QAnon’s epistemology with particular reference to the stated purpose of ‘research’ and its difference to an allegedly hegemonic (or ‘mainstream’) episteme. The article then turns to how these discourses are operationalised in the research tools QAnon.pub and QAgg.news (‘QAgg’). Finally, it concludes by way of a reflection on how QAnon’s aggressively counter-revolutionary strategies and infrastructures can trouble the concept of the ‘minor’ in minor tech.

Introduction

For the large part, the contributions to this issue have discussed instances of ‘minor tech’ that offer creative and necessary inverventions in tactics and infrastructures that are–in their deployment by big tech–exploitative, exclusionary, and often environmentally catastrophic. As such, the impression of minor tech may well be that its ‘small’ or ‘human’ scale necessarily precludes such tactics and technologies’ use in the service of a reactionary political project. Nevertheless, this article argues that QAnon can be understood as an assemblage of ‘minor techs’: small-scale contrarian practices and infrastructures whose very granularity produces the conditions for the aggregation that is known as ‘QAnon’ to occur and mutate from the cryptic missives of one ‘anon’ among many on 4chan’s /pol/ board in late 2017; to–in 2023–a global phenomenon with ominous implications for the question of post-truth’s effects on contemporary cultural and political life (see Rothschild; Sommer, Trust the Plan).

Andersen and Cox open this issue quoting Deleuze and Guattari’s definition of ‘minor literature’ as characterised by “the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective arrangement of utterance” (18). They go on to suggest that minor tech’s politics of scale potentially offer an analogous operation with regard to the production of autonomous – potentially revolutionary – spaces for marginalised groups. It is in this sense that this article’s contention regarding QAnon’s being a minor tech arises. Specifically, it is in the injunction to ‘do your own research.’ Among QAnon’s myriad factions the statement is a veritable refrain that characterises involvement in the phenomenon as more than simply believing its conspiratorial worldview, but rather participating in its production by investigating its veracity for oneself and, by implication, arriving at similar conclusions. While there has been some scholarly research into various aspects of QAnon’s participatory culture (de Zeeuw and Gekker; Kir et al.; Marwick and Partin; See), how this is conceptualised and enabled within the phenomenon through minor tech tactics and infrastructures remains comparatively understudied.

This article, accordingly, seeks to unpack how ‘research’ is understood within QAnon, and how this understanding is operationalised in the production of particular tools. Drawing on exemplar literature internal to the phenomenon, it will first examine discourses surrounding the question of QAnon’s inverted epistemology with particular reference to the stated purpose of ‘research’ and its perceived difference to an allegedly hegemonic (or ‘mainstream’) episteme. Following this analysis of QAnon’s internal discourses on the matter of ‘research,’ the discussion will then turn to how these discourses are reflected and enacted in the ‘Q Drop’ aggregators QAnon.pub and QAgg.news (‘QAgg’). Q Drops are QAnon subjects’ term for the ambiguous dispatches made by the eponymous, mysterious figure known as ‘Q’ which form the ur-text of the phenomenon. While there is a certain consistency to the Q Drops insofar as they are concerned with the actions of Donald Trump and his allies against the nefarious ‘Deep State’ or ‘Cabal’ who are alleged to have undermined the former party’s efforts to ‘Make America Great Again,’ they are also characterised by an extreme degree of vagueness which demands epistemic work on the part of the QAnon subject.

Since these materials have been posted exclusively to anarchic and unarchived image boards – first 4chan, then 8kun (formerly 8chan) – Q Drop aggregators scrape, archive, and afford users means do ‘research’ with the Q Drops. A notable feature of the Q Drop aggregators is their increasing complexity over time: where QAnon.pub (established March 2018) is effectively wholly concerned enabling the analysis of the content of Q Drops, QAgg (April 2019) mines Drops for actual and esoteric meta-data, supposedly encrypted additional information that pushes the Q Drops’ semiosis to the point of potential exhaustion. The increasing granularity of how Q Drops are interpreted and applied in the ‘research’ afforded by QAgg specifically reflects a broader tendency towards the molecular intensification of QAnon subjects and speaks to a broader argument regarding precisely the ‘minor’ quality of QAnon’s technical apparatuses that make its reactionary manifestation at scale possible.

‘Research’ at a human scale

Despite the centrality of Q to the worldview of QAnon, they do not present themselves as, nor are they taken to be, a prophet bearing a revealed truth. Instead, Q characterises themselves as instructing their followers in what might be understood as a degraded form of ideology critique wherein the asserted reality of the phenomenon’s worldview is rendered visible in the mediatic traces of the world:

You are being presented with the gift of vision.

Ability to see [clearly] what they've hid from you for so long [illumination].

Their deception [dark actions] on full display.

People are waking up in mass.

People are no longer blind. (Q Drop 4550, square brackets in original)[1]

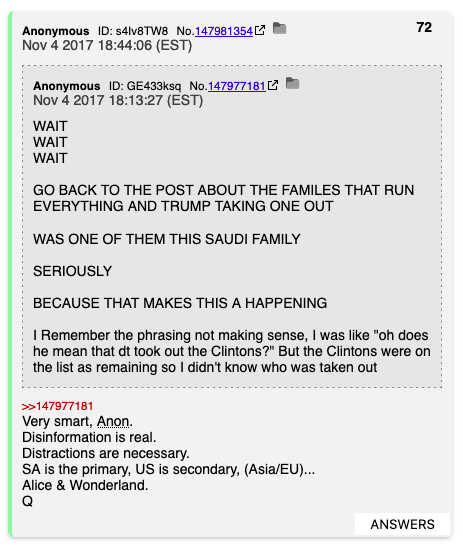

'Research’ in QAnon is typically characterised by the mapping of contemporary events to the content or metadata of Q Drops by QAnon subjects, with Q occasionally intervening to correct or confirm QAnon subjects’ inferences and findings. Beyond the initial series of Drops where Q claimed that the arrest of Hillary Clinton was imminent – “between 7:45 AM - 8:30 AM EST on Monday - the morning on Oct 30, 2017” (1) – they very rarely make explicit claims as to the future. Instead, Q tends to vaguely intone on contemporary events or ‘correct’/‘verify’ the findings of QAnon subjects. Here, the failed prediction that was the basis of the very first Q Drop is illustrative. While Hillary Clinton was not arrested, the 2017-2019 Saudi Arabian purge began some days after the first Q Drop (namely, on the 4th of November 2017) with a wave of arrests across the Gulf State. In response, a user of 4chan’s /pol/ board posited that it was in fact this event that Q was in fact alluding to (fig. 1). Per Q in their reply to said user: “Very smart, Anon. Disinformation is real. Distractions are necessary” (72). In essence, the first Q Drops were framed as about the then-forthcoming purge, with the discussion of Hillary Clinton being misdirection to run cover for this operation.

Rather than mirroring the didactic pedagogy and unaccountable epistemic hierarchies of the so-called "mainstream media" (Pamphlet Anon and Radix 93), Q is seen as instructing QAnon subjects in a particular way of seeing and mode of inquiry. As the QAnon promoter David Hayes (a.k.a. ‘Praying Medic’) explains in a passage on this topic that is worth quoting at length:

Q uses the Socratic method. Using questions, he’ll examine our current beliefs on a given subject. He'll ask if our belief is logical, then drop hints about facts we may not have uncovered, and suggest an alternative hypothesis. He may provide a link to a news story and encourage us to do more research. The information we need is publicly available. We're free to conduct our research in whatever way we want. We're also free to interpret the information however we want. We must come to our own conclusions because Q keeps his interpretations to a minimum. For many people, researching for themselves, thinking for themselves, and trusting their own conclusions can make following Q difficult. When you’re accustomed to someone telling you what to think, thinking for yourself can be a painful adjustment. (Hayes 17)

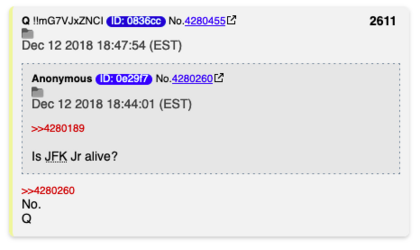

While Q possesses a certain authority in terms of having the proverbial ‘last word’ with regard to the work of QAnon subjects, this is not exercised in most cases. It is always the QAnon subject’s obligation to ‘do your own research’ – which is, again, the mapping of contemporary events to the content, metadata, and meaning of the Q Drops. Indeed, despite Q’s ostensibly ‘final’ authority with regard to what is and is not an aspect of the phenomenon’s worldview output, there are some instances where the figure has been effectively ignored due to the salience of the individual and their ‘research.’ For example, there many QAnon subjects who believe that the deceased son of the assassinated president John F. Kennedy – John F. Kennedy Jr. – is still alive (Sommer, “QAnon, the Pro-Trump Conspiracy Theorists, Now Believe JFK Jr. Faked His Death to Become Their Leader”), and this despite Q’s explicit denial thereof (fig. 2).

QAnon’s fetishization of individual interpretation as well as the salience of primary sources therein has been identified by Marwick and Partin as an instance ‘scriptural inference.’ Tripodi characterises scriptural inference as a prevailing epistemology among religious and right-wing actors in the United States wherein “those who believe in the truth of the Bible approach secular political documents (e.g., a transcript of the president’s speech or a copy of the Constitution) with the same interpretative scrutiny” (6). While Tripodi notes an analogous compulsion among their research subjects to “do their own research” (6), the extent to which epistemic authority is located in the ‘researching’ subject is unclear. In comparison, the centrality of a particular QAnon subject’s ‘research’ to themselves is an explicit refrain: even prominent QAnon promoters describe their findings with this qualification (Colley; Dylan Louis Monroe at Conscious Life Expo 2019; The Fall of the Cabal).

The overarching impression is that ‘research’ within QAnon is not so much about working towards the production of a body of knowledge that all QAnon subjects can agree upon rather than it is concerned with the proliferation of many personalised ‘truths.’ As in the Q Drops, as in the mediatic traces of the world–all are material available for the individual’s interpretation of one in terms of the other towards the production of increasingly personalised and complex ‘research.’ That these conditions work to produce an worldview that is characterised at the micro- and macro-levels by a swirling mess of complexity and contradictions is simply taken as evidence of the phenomenon’s good health; there is no ‘groupthink’ (Hayes).

Nevertheless, the phenomenon’s internal heterogeneity all points to the asserted ‘truth’ of QAnon’s worldview, with contrary analysis pathologized as either being the uncritical work of someone in the thrall of the ‘mainstream’ episteme or deliberately malicious efforts of the Deep State and its agents. Actual difference – being that which is definitionally other to a subject or particular set of conditions – is not tolerated within QAnon. What is true of the phenomenon’s epistemology is also true of its worldview and accounts for QAnon’s actual hostility towards minoritarian movements. To the QAnon subject, America being made ‘Great Again’ is a fantasy of fascist restoration, a perverted ‘end of history’ wherein the conditions for the different or new are permanently evacuated.

Scales of ‘Research’: the Q Drop Aggregators

While QAnon has arguably always been a cross-platform phenomenon (Zadrozny and Collins), the figure of Q themselves is closely associated with image boards 4chan, 8chan, and 8kun. Indeed, the primary mechanism though which Q’s dispatches are considered authentic is by way of their posting exclusively to the image board they call home–presently 8kun–with their current tripcode.[2] While providing a basically adequate means for performing the apparent provenance for these ambiguous missives, this practice of “no outside comms” (465) beyond the anarchic and ephemeral image boards where Q dwells generates a certain tension with the previously discussed injunction to ‘do your own research.’ In this respect, it is necessary to explain the technical conditions within which QAnon emerged in order to understand the parallel development of archival infrastructures.

4chan was launched in 2003 by the fourteen-year-old Christopher Poole as an English language clone of the Japanese board 2chan.ner (Beran). Given the lack of server space initially available to him, Poole elected to limit the number of threads on any given board and archive nothing. Combined with the site’s default username–‘Anonymous’–and a laissez-faire moderation policy, Poole somewhat unwittingly created the conditions for the emergence of an extraordinarily dynamic and culturally significant milieu whose influence can be seen across digital culture as well as in the strategies of activist groups ranging from Occupy Wall Street, to Anonymous, to – more recently – the ‘alt-right’ and QAnon (Coleman; Phillips et al.). 8chan, meanwhile, was launched in 2013 by Fredrick Brennan and became prominent among 4chan’s more reactionary users in 2014 as a ‘free speech’-guaranteeing clone of 4chan, which at the time had banned any mention of the misogynist witch-hunt known as ‘gamergate’ (Marwick and Lewis; Sandifer). In 2019, after the respective perpetrators of the Christchurch, Poway, and El Paso massacres associated themselves with the site, it was removed from the clearnet for approximately a month before relaunching as ‘8kun’ (Hagen et al.; Keen)

While the ephemerality of 4chan was initially a means to manage limited computational resources, this quality has since come to define the culture of ‘the chans’–the global array of websites with similar affordances and user cultures that include, but are not limited to 4chan, 8chan, and 8kun (see De Keulenaar). For instance, 4chan and 8chan are both characterised by the strictly limited number of active threads (200 for 4chan, 355 for 8chan/kun) with only the most commented upon (or ‘bumped’) persisting until they too – after running out of steam or reaching the boards’ ‘bump limit’ (300 and 750 comments, respectively) – are inevitably ‘pruned’ (permanently deleted) to make way for new posts. Given the febrile rate of posting among both boards’ extensive userbases, any given thread has a strikingly short lifespan in comparison to mainstream social media platforms with a significant amount of content being pruned within a matter of minutes and the longest-lived threads persisting for only a handful of hours (Hagen, “Rendering Legible the Ephemerality of 4chan/Pol/ – OILab”).

The prevailing view on this scalar compression of many users into an extremely limited discursive environment is that it applies a kind of Darwinian pressure on the content posted to the boards (Moot’s Final 4chan Q&A). As there are no archives, content only endures if it survives this evolutionary stress and enters the embodied memory of the userbase. Although there are user-developed mechanisms of reposting to ‘counter’ this ephemerality and allow discussions to continue over longer periods of time than might be possible otherwise – for instance, through the practice of creating and maintaining ‘general threads’ on a particular topic that are revived at the point of their reaching the boards’ bump limit –these nevertheless still primarily deal in the repetition of content by reiterating a particular line of argument, reposting a particular meme, etc., rather than archiving it (OILab). Indeed, despite the fact that there are extensive and accessible archives of these boards, these infrastructures do not really figure in the discourses of 4chan and 8chan/kun as it is occurring, or indeed, could not even be implemented given the feverish temporality of posting (Hagen, “‘Who Is /Ourguy/?”).

As a result, if one were to look for the Q Drops in-situ, they would find them spread across three websites, containing seven boards therein (chronologically: /pol/ on 4chan, then /CBTS/, /TheStorm/, /GreatAwakening/ on 8chan, and /QResearch/, /patriotsfight/ and /projectdcomms/ on 8kun) with local archives for these boards ranging from non-existent (4chan) to extremely patchy and unsearchable (8chan/kun), to say nothing about the veritable ocean of unrelated and likely obscene content that one would also encounter. Under such conditions, QAnon’s ur-text appears as a distributed and disjointed series of image board posts with unstable authorship. Q drop aggregators intervene at this point, collecting the (currently 4,399) Q drops into an online archive and presenting them as a coherent corpus through which ‘research’ can occur. QAnon subjects do not need to navigate the hostile interface and culture of a chan board–and few do (see “Do You Believe in Coincidences?”).[3] Instead, they can ‘research’ Q Drops at their leisure on the aggregators. Additionally, the Q Drop aggregators afford the circulation of Drops across the wider web, including the major corporate platforms despite QAnon’s ostensive ‘deplatforming’ after its pandemic-facilitated ‘boom’ and the events of 6 January 2020 (O’Connor et al.). In essence, by enabling distributed small scale acts of individual‘research’ on the part of QAnon subjects, Q drop aggregators facilitate the production of QAnon at the immense scale that the phenomenon has achieved. The paper will now proceed with a comparative analysis of how two major Q Drop aggregators (QAnon.pub and QAgg) make their materials available for users’ ‘research’ efforts.

QAnon.pub

QAnon.pub’s domain was registered on the 7th of March 2018 (DomainTools, Whois Record for QAnon.Pub) and captured by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine on the 9th of the same month. As such, it is not only the oldest of the aggregators discussed in this article, but is also very likely to have been the first of the Q Drop aggregators. Indeed, its pseudonymous developer (‘qntmpkts’) is credited with aiding in the development of the open-source 8kun scraping software that is basis of many other Q Drop aggregators (see Aliapoulios et al.; QAlerts). At the time of writing QAnon.pub’s collection consists of 4,966 Q Drops, 110 Q Proofs, and 349 ‘answers’ to specific drops.

QAnon.pub’s interface presents the user a reverse-chronological grid of Q Drops, bearing essentially the same metadata that would appear on a chan board–albeit without the measures of direct engagement à la the list of replies that would appear on the post in-situ; as well as lacking the context that would account for the salience of the tripcode, thread ID, and post number (fig. 4, 5). Drops are also grouped according to the date they were made and numbered for–presumably–ease of reference. Insofar as the material of the Q Drops themselves is concerned, their articulation in QAnon.pub suggests that the aggregator is concerned with the simple provision of the Q Drops as – essentially – texts.

Such an impression is furthered in the aggregator’s affordances. The search bar is a simple filter for the content of the Q Drops (one cannot search a particular Drop number or filter by date, for example), the Drops can only be ordered in chronological or reverse-chronological sequence, and the child window that appears when clicking “ANSWERS” button displays a line-by-line of the Drop by way of text taken from the ‘STORM is HERE’ spreadsheet, and occasionally via a Q proof (fig. 6, 7).[4] Here, in essence, Q Drops (which were originally distributed in time and space) are formatted in such a way that they resolve into a larger text, and as such QAnon.pub enables the analysis of their textual and narrative elements–in linear time–more or less exclusively.

QAgg

QAgg’s domain was registered on the 3rd of November 2019–although the site’s changelog states that the site itself was launched on the 3rd of April 2019 (see DomainTools, Whois Record for QAgg.News; TechmasterQ). At the time of writing (April 2023), the site has been down since late November/early December 2022. In addition to its 4,966 Q Drops, QAgg also maintained extensive archives of posts made to Twitter, Gab, and TRUTH Social by QAnon-relevant figures.

Likely as a result of its being the most recently established major Q Drop aggregator, QAgg is the most complex example of such an archival infrastructure within QAnon. Here, ‘complex’ is not intended to suggest sophistication or legitimacy on the part of QAnon’s ‘researchers’ or their methods, but more akin to a kind of paranoid psychosis where the Q Drops and other are rendered available ‘researched’ at increasingly molecular scales of detail and abstraction. On QAgg, this impulse is most evident in the aggregator’s emphasis on metadata.

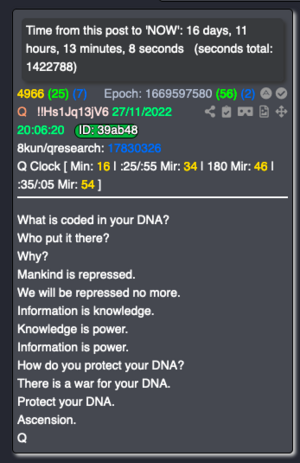

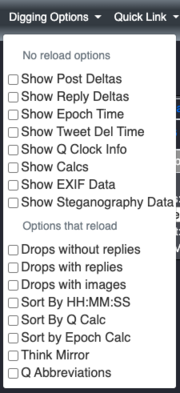

While users can engage with QAgg in a largely textual capacity as one would consult QAnon.pub, the utility of QAgg is in how the aggregator makes the metadata of Q Drops available for users’ ‘research’ (fig. 9). This metadata ranges from the relatively grounded provision of a Drop’s timestamp in unix epoch time and the analysis of the EXIF data in the images of a given Drop to the decidedly esoteric in the form of numerology and ‘deltas.’ The visibility of metadata is toggled by way of the site’s ‘digging options’ (fig. 9), which also affords the ability to filter or rearrange the order of the materials in the interface. QAgg’s search, furthermore, affords the use of sophisticated queries wherein a user can search the aggregator’s materials by date and time (or a range thereof), by Q clock minute, platform or ‘player,’ as well as using Boolean ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ operators to string these specific queries together (TechmasterQ).

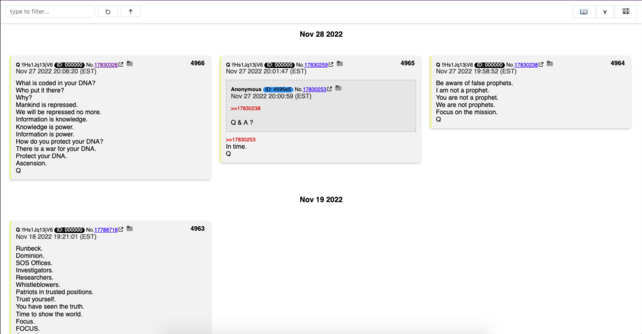

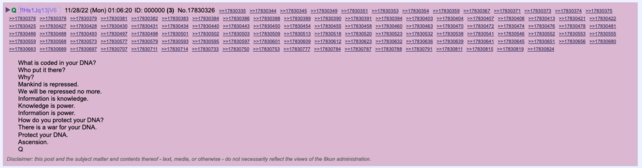

Given that QAgg’s archive contains a wealth of additional materials (Twitter, Gab, and TRUTH Social posts from several figures who have–in one way or another–become incorporated into QAnon’s worldview), the act of mapping Q Drops onto the external materials and events in the world is effectively automated by way of the various means of corpus-building within its interface. In essence, the affordances of QAgg represent the methodological avant-garde of QAnon ‘research,’ wherein every thinkable mechanism for the extraction of meaning, bringing into relation, and ultimate production of ‘research’ findings have been operationalised upon its materials–and if these affordances are not sufficient than a user can go to QAgg’s ‘Data Science’ tab and download JSONs or CSVs of QAgg’s archives and perform whatever further analysis upon these materials they wish. Although QAgg’s preoccupation with metadata speaks to a certain effort towards the appropriation of data science’s methods in the aggregator, the provision of these files warrants further reflection. Specifically, because it represents an attempt to utilise technical apparatus of neoliberal governmentality and epistemology (Chun) – aspects of the QAnon subject’s alleged ‘oppressors’ – towards furthering the epistemic basis of the phenomenon’s fascist worldview.[5]

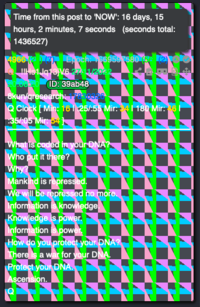

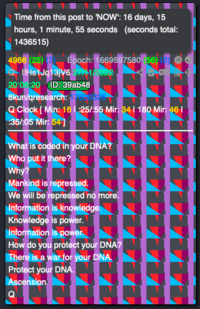

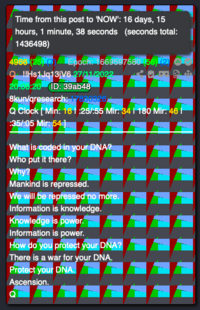

While the actual content of QAgg’s materials is effectively secondary to their metadata, QAgg nevertheless offers several means through which users can share Q Drops to other platforms and, therefore, facilitate the dissemination of their ‘research.’ This includes means to generate a direct link to a given Q drop, copy its text, or generate a jpeg image of it as it appears on QAgg. The most interesting distribution tool, however, is ‘digital camo.’ This affordance produces a randomly generated dazzle camouflage pattern underneath the content of a Q Drop in an effort to evade image recognition-based moderation systems and therefore–in theory–allow for the circulation of Q drops on platforms where QAnon has been banned (Facebook, Google, Twitter, see also fig. 10). Whether or not such mechanisms of evasion work, such anticipation of machinic moderation speaks to questions of QAnon’s potential to develop minor tech in the recognition and subversion of platform governance strategies. It also speaks to particular mechanisms of subject formation within QAnon where the stigmatisation of this material serves to reify it as – essentially – ‘what they don’t want you to see’ (see Barkun). That the effort to subvert this marginalisation takes the form of a camouflage is also instructive as it speaks to the militaristic ontology of the QAnon subject; they are not just ‘researchers,’ but “digital soldiers” (Roose) in an insurgency.

|

|

|

| Figure 10: Some examples of digital camo as applied to Q drop 4966. | ||

Conclusion

While QAnon is definitionally ‘minor’ in the scale of its technical apparatuses and insofar as it too is characterised by “the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective arrangement of utterance” (Deleuze and Guattari 18), the fascist ontology and political project that these tactics and infrastructures produce suggests a certain point of difference that warrants further reflection. That is, where the minor is typically concerned with generating – or making space for – difference within the linguistic/technical apparatuses of a hegemon or oppressor, the space of epistemic difference that QAnon has carved out for itself is only different insofar as it is opposed to the political and epistemic order of the neoliberal regime, while remaining essentially hostile to that which remains Other. In fact – and despite the epistemic heterogeny of the phenomenon – all ‘research’ effectively points to the asserted truth that the phenomenon’s worldview bears the decidedly more concerning implication that the final purpose of the QAnon’s minoritarian tactics and tech is aggressively counter-revolutionary. Namely, it is intent on the erasure of difference from the social formation in favour of a reconfiguration of symbolic authority towards the so-called ‘restoration’ of what is perceived to be the QAnon subject’s ‘rightful’ subject position. The increasingly molecular scale of ‘research’ in QAnon can, therefore, be understood as an effort towards scaling down the world’s heterogeny and difference within the flat onto-ideological field of QAnon’s worldview, which potentially accounts for the deterritorializing vitality of this ‘conspiracy of everything’ (Rothschild). QAnon’s tactics and infrastructures can, therefore, trouble the concept of the minor; and suggest a need to grapple with questions of scale, subjectivation and the technicity of ignorance in addressing the problem of contemporary fascisms.

Notes

- ↑ Hereafter Q Drops are referenced as ‘(Drop number).’ Drop numbers are digits that mark where a particular Drop is located in the chronological sequence of Q’s posts as they appear within the interface of a Q Drop aggregator. While there is some disagreement as to what is and is not an authentic Q Drop among Q Drop aggregators and therefore some disparities in the Drop numbers for specific Drops (Aliapoulios et al.), the numbering of Q Drops between this paper’s case studies is identical and therefore used herein.

- ↑ Per Drop 465 (after the Q’s move from 4chan to 8chan due to the latter’s being ‘compromised’): “No other platforms used. No comms privately w/ anyone.” In reality, this move (platform and rhetorical) was likely an effort on the part of one of the individuals behind Q to consolidate their control over the account (see “Calm Before the Storm”). A tripcode is a cryptographic hash of a user’s password which, when implemented, essentially acts as a username in that it allows for a user to be identified on the typically entirely anonymous chan boards.

- ↑ Many QAnon subjects may, in fact, be entirely unaware of the boards. For example, the Capitol Riot’s ‘poster boy’ (Hsu) Doug Jensen–in an interview with FBI agents a few days after the events of January 6th–located the origin of the phenomenon in a Q Drop aggregator (either QAnon.pub or QMap): “it started off on Twitter – no, it started off with q.pub, and then q.pub got shut down, and now I have another one, it's like qalert.something” (Jensen 7).

- ↑ Based on the document’s comment history (as version history is unavailable) the ‘STORM is HERE’ spreadsheet appears to have been a collaborative effort at a line-by-line analysis of all Q drops in chronological order hosted on Google Sheets. Although at the time of writing the document has now been taken down by Google for violating the platform’s terms of service, an archived version from the 17th of March 2022 can be accessed via the following link: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1eQXM6KLDcVGyMXhqJxNFyA8TvBoSibvFRZOVYaMPjT8/edit?usp=sharing

- ↑ See also Lee et al. on Covid-19 sceptics’ use of analogous rhetoric and methods towards similarly reactionary aims.

Works cited

Aliapoulios, Max, et al. “The Gospel According to Q: Understanding the QAnon Conspiracy from the Perspective of Canonical Information.” ArXiv:2101.08750v2 [Cs], May 2021. arXiv.org, https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.08750v2.

Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. University of California Press, 2003.

Beran, Dale. It Came from Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Accidentally Memed Donald Trump into Office. First edition, All Points Books, 2019.

“Calm Before the Storm.” Q: Into the Storm, directed by Cullen Hoback, 1, HBO, 21 Mar. 2021.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Programmed Visions: Software and Memory. The MIT Press, 2011.

Coleman, E. Gabriella. Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous. Verso, 2014.

Colley, Lori. “The Day I Knew Q Wasn’t a Hoax.” QAnon: An Invitation to the Great Awakening, edited by Captain Roy D and Dustin Nemos, 2019.

De Keulenaar, Emillie. “Freedom and Taboos in the International Ghettos of the Web – OILab.” OILab, 2018, https://oilab.eu/freedom-and-taboos-in-the-international-chanosphere/.

de Zeeuw, Daniël, and Alex Gekker. “A God-Tier LARP? QAnon as Conspiracy Fictioning.” Social Media, 2023.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

“Do You Believe in Coincidences?” Q: Into the Storm, directed by Cullen Hoback, 2, HBO, 21 Mar. 2021.

DomainTools. Whois Record for QAgg.News. https://whois.domaintools.com/qagg.news. Accessed 28 June 2022.

---. Whois Record for QAnon.Pub. https://whois.domaintools.com/qanon.pub. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Dylan Louis Monroe at Conscious Life Expo 2019. Directed by Deep State Mapping Project, 2019. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzVW3KR1Dqw.

Hagen, Sal, et al. Infinity’s Abyss: An Overview of 8chan – OILab. 2019, https://oilab.eu/infinitys-abyss-an-overview-of-8chan/.

Hagen, Sal. “Rendering Legible the Ephemerality of 4chan/Pol/ – OILab.” OILab, 2018, https://oilab.eu/rendering-legible-the-ephemerality-of-4chanpol/.

---. “‘Who Is /Ourguy/?’: Tracing Panoramic Memes to Study the Collectivity of 4chan/Pol/.” New Media & Society, Feb. 2022, p. 146144482210782. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221078274.

Hayes, David. Calm Before the Storm. Self Published, 2020.

Hsu, Spencer S. “QAnon ‘Poster Boy’ for Capitol Riot Sent Back to Jail after Violating Court Order to Stay off Internet.” Washington Post, 2 Sept. 2021. www.washingtonpost.com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/legal-issues/douglas-jensen-jailed-qanon-addiction/2021/09/02/50ee9628-0c08-11ec-aea1-42a8138f132a_story.html.

Jensen, Douglas. Interview of: Douglas Austin Jensen. Interview by Tyler Johnson and Scott James, 8 Jan. 2021, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21581097/jensen-transcript.pdf.

Keen, Florence. “After 8chan – Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats.” Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats, 4 Nov. 2020, https://crestresearch.ac.uk/comment/after-8chan/.

Kir, Freja, et al. Scientometrics of Conspiracy Creation: Tracing Conspiracy Making on 4Chan. University of Amsterdam, 2020, https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/QAnon-ScientometricsofConspiracyCreationTracingConspiracymakingon4Chan.

Lee, Crystal, et al. “Viral Visualizations: How Coronavirus Skeptics Use Orthodox Data Practices to Promote Unorthodox Science Online.” Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2021, pp. 1–18. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445211.

Marwick, Alice, and Rebecca Lewis. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. Data & Society Research Institute, 2017.

Marwick, Alice, and William Partin. “Constructing Alternative Facts: Populist Expertise and the QAnon Conspiracy.” New Media & Society, 2022, p. 21.

Moot’s Final 4chan Q&A. Directed by 4chan, 2015. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYUKJBZuUig.

O’Connor, Ciaran, et al. The Boom Before the Ban: QAnon and Facebook. Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 12 Dec. 2020.

OILab. The Baker’s Guild: The Secret Order Countering 4chan’s Affordances – OILab. 2018, https://oilab.eu/the-bakers-guild-the-secret-order-countering-4chans-affordances/.

Pamphlet Anon and Radix. “Changing the Narrative: Trump and the Media.” QAnon: An Invitation to the Great Awakening, edited by Captain Roy D and Dustin Nemos, 2019, pp. 93–104.

Phillips, Whitney, et al. “Trolling Scholars Debunk the Idea That the Alt-Right’s Shitposters Have Magic Powers.” Vice, 22 Mar. 2017, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/z4k549/trolling-scholars-debunk-the-idea-that-the-alt-rights-trolls-have-magic-powers.

QAlerts. “Sqraper: PHP 8Kun Q Post Scraper.” GitHub, 5 June 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20200605191831/https://github.com/QAlerts/Sqraper.

Roose, Kevin. “A QAnon ‘Digital Soldier’ Marches On, Undeterred by Theory’s Unraveling.” The New York Times, 17 Jan. 2021. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/17/technology/qanon-meme-queen.html.

Rothschild, Mike. The Storm Is upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy Theory of Everything. Monoray, 2022.

Sandifer, Elizabeth. Neoreaction a Basilisk: Essays on and around the Alt-Right. 2018.

See, Rose. From Crumbs to Conspiracy: Swarthmore College, 2019.

Sommer, Will. “QAnon, the Pro-Trump Conspiracy Theorists, Now Believe JFK Jr. Faked His Death to Become Their Leader.” The Daily Beast, 2 Aug. 2018. www.thedailybeast.com, https://www.thedailybeast.com/qanon-the-pro-trump-conspiracy-theory-now-believes-jfk-jr-faked-his-death-to-become-its-leader.

---. Trust the Plan: The Rise of QAnon and the Conspiracy That Reshaped the World. 4th Estate, 2023.

TechmasterQ. “FAQ.” QAgg.News, https://qagg.news. Accessed 31 Oct. 2022.

Tripodi, Francesca. Searching for Alternative Facts. Data & Society Research Institute, 16 May 2018, p. 64.

The Fall of the Cabal. Directed by Janet Ossebaard, 2020, https://www.bitchute.com/video/aDjnD3tsbFSH/.

Zadrozny, Brandy, and Ben Collins. “How Three Conspiracy Theorists Took ‘Q’ and Sparked Qanon.” NBC News, 15 Aug. 2018. www.nbcnews.com, https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/how-three-conspiracy-theorists-took-q-sparked-qanon-n900531.