Toward a Minor Tech:AnikinaKeskintepe5000: Difference between revisions

m (→Endnotes) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Toward a Minor Tech]] | [[Category:Toward a Minor Tech]] | ||

[[Category:5000 words]] | [[Category:5000 words]] | ||

= Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice in Media Arts and Resistant Tech = | = Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice in Media Arts and Resistant Tech = | ||

xenodata co-operative (Alexandra Anikina, Yasemin Keskintepe) | |||

== Abstract == | == Abstract == | ||

Revision as of 13:06, 22 June 2023

Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice in Media Arts and Resistant Tech

xenodata co-operative (Alexandra Anikina, Yasemin Keskintepe)

Abstract

Speculative narratives of (techno)magic such as those offered by feminist technoscience, cyberwitches and techno-shamanism come from knowledge systems long marginalised in a hyper-optimised and hard-science-reliant capitalist discourse. Aiming to de-centre Western rational imaginaries of technology, they speak from decolonial and translocal perspectives, in which the relations between humans and technology are reconfigured in terms of care, relationality and multiplicity of epistemic positions. In this paper, we consider (techno)magic as an act of transgressing a knowledge system plus relational ethics plus capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from commodified forms of belief and knowledge and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine. What critical approaches, epistemic and aesthetic procedures do these speculative practices enable in media art and resistant tech? In what ways does “magic” act as an alternative political imaginary in the age of hegemonic Western epistemologies? Drawing on feminist STS and the works of artists such as Choy Ka Fai, Omsk Social Club, Ian Cheng, Suzanne Treister and others, we propose to address (techno)magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice.

Sorcery? It is a metaphor, of course? You don't mean that you believe in sorcerers, in 'real' sorcerers who cast spells, transform charming princes into frogs or make the poor women who have the bad luck to cross their path infertile? We would reply that this sort of accumulation of characteristics translates what happens whenever one speaks of the 'beliefs' of others. There is a tendency to put everything into the same bag and to tie it up and label it 'supernatural’. What then gets understood as 'supernatural' is whatever escapes the explanations we judge 'natural’, those making an appeal to processes and mechanisms that are supposed to arise from 'nature' or 'society’. – Philippe Pignarre and Isabelle Stengers, Capitalist Sorcery: Breaking the Spell

Introduction

Recent exhibitions demonstrate an interest in technology as connected to, intermixed with or implicated in magical practices. Inke Arns’ Technoshamanism (2021) at HMKV Hartware MedienKunstVerein, in Dortmund, Germany, was, perhaps, the most directly relevant to the topic. Post-Human Narratives—In the Name of Scientific Witchery (2022) at Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences, curated by Kobe Ko, explored para-scientific, esoteric and unorthodox medical practices mixing science and witchcraft. Wired Magic (2020) at Haus der Elektronischen Künste Basel, curated by Yulia Fisch and Boris Magrini, focused on the rituals and methods of artists intertwining magical practices with technology. Recently, The Horror Show! (2023) at Somerset House, London, contained a section titled Ghost, which outlined the British history of post-spiritualist hauntologies of electronic media.

As Jamie Sutcliffe notes at the launch of Magic, a collection he edited in the Whitechapel series Documents of Contemporary Art, the interest towards magical practices in arts reemerges every few years. [1] However, the specific intersection of the magical and the technological also tends to follow waves of innovation and the consequent waves of anxiety about technology within public discourse (as can be seen even in the recent rise in apocalyptic debates about artificial intelligence after the launch of ChatGPT). They often refer to the famous quote by Arthur C. Clarke: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” (Clarke, n.p.). What does this quote say about these debates? More often than not, it is understood as a necessity for linear progress: if technology is to advance sufficiently, it must undergo the process of development. It also implies that advanced technology cannot avoid being opaque: its internal operation must be inaccessible to the use, casting the human-technology relationship into the categories of 'belief' or 'trust'.

The anxiety-driven narratives tend to forego the issues of ethics and care in favour of driving catastrophic imaginaries of technology. With this in mind, we would like to situate our proposition of (techno)magic by taking it outside of the binary of rationality and irrationality. Rather, we would organise it around the following question: what place is accorded to magic in the current discourses of technology, both fueled by and shielded from practices of belief?

Situating (Techno)magic

If we approach magic and technology as fields of knowledge with specific genealogies, we will often find them entangled. Erkki Huhtamo outlines the archaeology of magic in media, pointing out that the development of media technologies is closely tied to magic, from Mechanical Turk to moving images and animation (Huhtamo). In the West, the Victorian history of spiritualism and mesmerism, ghost photography and technologically aided 'neo-occult' séances directly connected supernatural forces, energies and spirits with the newly introduced technological and scientific advancements (see Chéroux et al., Mays and Matheson). Jeffrey Sconce in Haunted Media addresses a particular kind of electronic presence, “at time occult” sense of liveness or “nowness” that inhabits the electronic media. This history extends back to the invention of modern means of communication that introduced simultaneity and immediacy as radically new types of experience of other people’s voices and images, such as with the introduction of telegraph by Samuel Morse in 1844 in the USA, or photography by Louis Daguerre in 1839 in France. [2] These histories (while a close look at them is beyond the scope of our current exploration) bring an interesting dimension to the intersections of magic and technology.

First of all, the contemporary idea of 'magic' itself is constituted and situated as a term created by Western modern technologies and Western orientalism, where the inevitable categorisation of unexplained phenomena either as scientific truths or as magical illusions played a significant role in the construction of the myth of contemporary science as rational and infallible. Secondly, while 'magic' as a term serves to further underscore the terms 'science' and 'technoscience' as rational, magic as such simply refers to alternative knowledge systems in which the myth of rationality is not the dominant one, and other cosmologies can come to the fore. Depending on how magic is understood within these two senses (as a Western term for everything irrational or as a word referring to cosmologies outside of it), and what kind of knowledge system stands behind it, we can construct multiple interpretations of magic, including the ones where magic is read as modernity’s ultimate technology, and ones where magic is proposed as alternative to technology. In line with the first understanding, Arjun Appadurai speculates that “capitalism… can be considered the dreamwork of industrial modernity, its magical, spiritual and utopian horizon, in which all that is solid melts into money” (481).

The second understanding of magic as an alternative to technology can be approached through the work of Federico Campagna, for whom Magic and Technic are two of the many possible “reality-settings” - “implicit metaphysical assumptions that define the architecture of our reality, and that structure our contemporary existential experience” (4). He sees Magic as oppositional to Technic: if Technic’s first-order principle is the knowability of all things through language, Magic’s first and original principle is that of the “ineffable”, where “the ineffable dimension of existence is that which cannot be captured by descriptive language, and which escapes all attempts to put it to ‘work’ - either in the economic series of production, or in those of citizenship, technology, science, social roles and so on” (10). While we do not agree on the juxtaposition of Technic to Magic, we find the exploration of “the ineffable” a very important distinction, especially for the quantified world of digital culture: “being put to work” means not only the physical labour process, but also various data being put to work within a statistical model, or being valorised in any other way.

The domain of the (techno)magical is the domain of epistemic acts, or acts of knowledge construction, especially in media arts and resistant tech practices. We are also interested in seeing the potential impact of such reframing on the ethics and epistemics of human-technology interaction and for developing relations of care with and via technology with others and the world. We approach this from the perspective of our encounters with the concepts of magic in the Western art and technology scene, and from our positions as Western-educated curator-researcher and artist-researcher.

It is also important to underline that the kind of 'magic' that we mean comes from contemporary artistic research where the magical is interpreted politically: borrowing further from the discussion of Documents of Contemporary Art, we are not interested in “esoteric transcendentalism or results-based magic” but rather in “the aspect of ritual that allows for an encounter with otherness in the self”, or “wonderment” (Whitechapel Gallery). Magic, and especially magical rituals, serves as a de-habituation from the naturalised behaviours of epistemic systems we find ourselves in.

What we call (techno)magic, then, is understood, first of all, as an act of granting access to an alternative knowledge system. It retains the "techno" part in brackets in order to preserve doubt about the false separation of the types of knowledge represented by the two parts. (Techno)magical constructs in media art and resistant tech can act as interventions into knowledge frameworks of late techno-capitalism, extending the relations of care and dissolving the hierarchies of knowledge production inherited from Western modernity.

The urgency of such care within the entanglements of technology with the world is particularly clear now. As Eduardo Viveiros de Castro argues, Anthropocene-thinking requires reassessing the predominant modes of operation in order to consider the heterogeneity of living and being in the world. In Technoshamanism (2021), Inke Arns underlined ecology as the central idea of the exhibition; for her, the return to shamanic and animist practices “has to do with the fact that we are living in a time when we realise that the system we have had up to now is also serving to destroy the world as we know it” (Arns). The turn toward alternative knowledge systems also allows implement change in the contemporary conceptions of technology, along with speculations on what kind of world they could engender. The ecological, feminist, decolonial approach is crucial in (techno)magical practice.

What we also want to emphasise against the backdrop of other entanglements of technology and magic, is that the question lies not only in the opposition of magic to technoscience within the rationality-irrationality binary, but also in what potential is there for the magical to reinscribe the discredited meanings of the notion of belief. The magical, in the sense that we propose to consider here, activates a different modality of the word 'belief' than the commodified belief systems within capitalism. Rather, belief stands for a long-denied possibility of an alternative political imaginary (one that, as Mark Fisher suggests, is excluded within capitalist realism (Fisher)). Within capitalism, belief can only be exercised without judgement within the confines of certain institutions, such as a temple, a church, a hospital, a rave, or an art space. In the same way that it discredits other belief systems, the neoliberal mind does not allow 'magic' into realms of serious consideration, inflecting it with a categorical epistemic downgrade, especially when it comes to research.[3] It is also not by mistake that the most popular magical story of the last thirty years is, essentially, a bureaucratised and regulated environment of a school for wizards. Therefore, in our thinking, this is the core provocation of magic: it activates the systems of belief in a space where they are not supposed to be activated. And non-religious belief seems like a precondition for convivialist politics of coexistence, joyful labour, care and non-hierarchical relationality.

At the same time, we are not suggesting that magic is a universal solution to capitalism; it's not possible to exit into magic as some kind of a primordial innocent state, and no knowledge system can play a role of a 'noble savage' at this point in history. To us, magic is a granular, messy middle situated between sliding and not always matching scales of epistemic conditions and politics. This is important in the processes of construction of belief in relation to the scale of technology, which operates differently at the levels of “minor tech” (Andersen, Cox) and at the scaled-up, infrastructural level of corporations and states.

These considerations situate our definition: we understand (techno)magic as an act of transgressing a knowledge system plus relational ethics plus the capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. (Techno)magic offers two immediate propositions, in that it 1) accepts 'naturecultures' instead of a binary divide between technology and nature; and 2) inserts new granular relationalities between existing extremes, creating 'minor' rather than grand narratives.

In the first proposition, (techno)magic could be called “ethico-onto-epistemological”, following Karen Barad’s suggestion of the inseparability of ethics, ontology and epistemology (Barad, 90), precisely because it exists at the intersection of politics of nature and culture that argues against separation of these philosophical entities, and because it lends itself to problematising the experiences of the self and being-in-the-world.

Returning to the second proposition, in which (techno)magic complicates the relations of scale by inserting granular relationalities, technology, in relation to magic, should be liberated from being a despirited tool (a hammer), or from being a magic-wand type solution to the world’s problems; (techno)magic activates a possibility of the ineffable, and therefore, uncapturable of magic in certain space-times inside techno-capitalist infrastructures. (Techno)magic does not simply become a technological prosthesis, but also does not become completely externalised as a miracle. Rather, its minor narratives are about acts of personal becoming political through interaction. The relationality of 'becoming-familiar' with the machine can be read as a literal familiarising yourself with a machine or technology that is unknown, and experiencing joyful co-production once the machine becomes known to the body and to its epistemic operation. But it can also be read as becoming-closer, like a familiar of a witch, meaning a useful spirit or demon (in European folklore) with whom a contract is made to collaborate. What is important here is the context of opening up new capacities to act, or capacities to act differently in a reality that was previously hidden.

Having proposed to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice, we would like to offer methodological speculation on what kind of practices could be considered within the remit of the (techno)magical, following these two propositions. One example is a ritual-based work by artist Choy Ka Fai. Rituals are important relational practices since they weave together physical bodies through a set of symbolic actions that allow participants to build relationships with each other, with technologies, as well as other entities with the aim of bringing forth a transformational process for the self.

Choy Ka Fai’s audio-visual performance Tragic Spirits (2020) from his project CosmicWander (2019-ongoing) investigates how shamanic rituals in Siberia in their histories and present constitutions intersect with broader environmental, technological and political shifts. The performance combines audiovisual sequences (which include documentary footage of the artist's journey and 3D visualisations) with a dance performance. While the human dancer performs on stage, her movements are mirrored by a virtual avatar on the screen, transmitted by motion capture.

The work suggests the interconnectedness between the human body, nature, ritual and technology, culminating in the phrase “I have arrived at the centre of the universe - the universe inside you [me]” (Choy) that appears on the screen during documentary sequences. What Choy Ka Fai suggests is reaching a place and a state of deep connectedness attained through oscillation created by the many components of the ritual. The audio-visual experience, employing music and intense visuals, reaches the point where the energy of sound vibration is felt as a bodily encounter with the magical reality of the 3D figure on the screen.

Speaking of (techno)magic in the case of Choy Ka Fai’s work offers an opportunity to consider what kind of relationality the technological aspects of the work enable in relation to the spiritual ones. While the technology of motion capture in itself focuses on quantifying and abstracting the lived experience and often serves the monetisation and further capture of data’s value, in Tragic Spirits it seems to be employed towards another goal, namely, mediating the experience of facing the ineffable. The movement between the documentary film, the dancer, the music and the avatar creates a closed circuit loop between the bio-techno-kinetics and their representation on the screen. In doing so, the performance weaves the 'blackbox' of technology within a sacred ritual. The motion capture animates the avatar on the screen, allowing the viewers to see the connection between it and the dancer. Yet, considering this bond and the dancer in the traditional sense of shaman entering an altered state of consciousness, the viewers don’t make the same journey as her - the motion capture can mediate and make visible, but can not abstract or data-fy the spiritual journey. This is, precisely, one of the major points of the work: the unknowable must be confronted, seen, heard and experienced without being subsumed.

The potential for human-technology relationality that extends beyond the instrumental and the techno-solutionist, of course, doesn’t have to be restricted to media art or research contexts. It can be traced to a variety of lived experiences of technology, from mundane to techno-spiritual. However, it is in artistic practices that we find useful fissures and tensions, and where politics have the potential to become most immediately visible and negotiated.

Decolonising (Techno)magic

Having established (techno)magic as human-technological relationality, it becomes necessary to further situate it in relation to the ethics and politics of being human: by whom and for whom should this relationality be redefined? Magic has also served as one of the “categorical fictions that would justify both the non-Western and Euro-American proletarian superstitions by colonial and governmental expansion” (Whitechapel Gallery). Seen as an instrument of imperialism and colonial violence, magic designated what kind of worlds and knowledge systems can exist and, by extension, what kind of environments can be destroyed and what kind of voices will be excluded and dominated. Feminist and decolonial (techno)magic, then, needs to engage with the concepts of positionality, care, labour, and embodied experience of life, and demonstrate a particular type of embeddedness that entails awareness of relationality and multiple ontologies.

The recent work of writer and technologist K Allado-McDowell, whose book Air Age Blueprint weaves theory, poetry, AI-generated text and diagrams in what can be read as a manifesto of cybernetic animism and interspecies collaboration. Allado-McDowell constructs a blueprint of a world where AI allows a wider sense of communication and understanding of non-humans, and where human consciousness is augmented entheogenically,[4] meeting this new universe halfway. While the concept of (techno)magic finds parallels with this imaginative work, as it does with the concept of procedural animism (Anikina), it also finds some differences in the treatment of the role of the human. Reading it both as inspiration and with productive critique, we first trace the question of the possibility of decolonial embedded-ness of non-Western cultural traditions in the Western context; and then consider how to position (techno)magic closer to the applied practices of care, relationality and labour.

Air Age Blueprint underlines the importance of belief systems in the current techno-cultural moment:

The age of the human is defined by our quantifiable effects on natural systems… These effects are in inheritance, the expression of a genetic trauma in the belief systems and sociotechnical structures of the modern West, a kind of curse. Redesigning infrastructure away from Anthropocenic destruction is one way of breaking this curse. But to do this we need a new set of beliefs and a new imaginary (67).

For Allado-McDowell, the new imaginary is built on the premise of “interspecies intelligence” (70), achieved through a combination of entheogenically altered perception and AI sensing systems that would make the natural world not only legible to humans but also deeply understood and acknowledged: “the goal is to articulate an Earth-centric myth that meets the requirements of human flourishing in an ecosystem where humans are recognised as animals dependent on birdsong or jaguar vitality for their survival and thriving” (70).

Allado-McDowell underlines that they conceive of “non-speciest thinking of Indigenous cosmologies and shamanic spirituality as a diverse set of ecological epistemologies: different ways of knowing not just through reason or intuition, but also on the level of ontology and practice” (71). This upholds the initial question: how do we conceive of the lifeworlds of others as 'ecological epistemologies' without assimilating them into the language and operation of the late liberalism and Western epistemology - one could argue, often in the same way that the words 'shaman' and 'shamanic' already do?

Allado-McDowell offers precise critiques of that possibility. They are acutely aware that the proposition for the combination of ecological awareness, technology and entheogenic culture can be (and already is to some extent) subject to capitalist capture and extraction. This is true as much for technology (wearables, augmented reality, global connectedness) and shamanic practices (alienated from their original context and reframed as mindfulness or self-care), as it is for entheogenic practices that are being subsumed and redeveloped as novel psychedelic compounds. To decolonise entheogenesis, Allado-McDowell underlines, the crucial steps are required: “more interrogation of the Anthropocene, associated environmental reversals and technoscientific instrumentalism”, combined with urgent critique of capitalism (77).

Air Age Blueprint seems to come from a particular context of capitalism that puts emphasis on entheogenesis, the universalised image of ‘ecosemiotics’ and references to transhumanism and cybernetics. The narrative proposes outlets for emancipation, yet they seem to circulate within the boundaries of the individual rather than collective practice (at least in human terms). At the end of the book, the main character, a filmmaker and poet, freelances as a beta-tester of a new AI program, Shaman.AI. The character is prompted to ‘contaminate’ the database with indigenous knowledge structures they encountered early in the narrative in the Amazonian rainforest while being taught by a healer. The metaphor of contamination, while already existing in real-life interactions with machine learning systems as ‘prompt injection’ (or ‘injection attack’, in cybersecurity language) is, at the same time, a proposal for subversive action and an acknowledgement of the near-impossibility of direct resistance.

Where Allado-McDowell suggests that a future ecosemiotic AI translating between the human and non-human worlds is construed as “what in the Amerindian view might look like a shaman” (71), bringing the Amerindian epistemology into the Western one, we would like to continue the line of questioning into the specific Western politics of imagination, care and labour without choosing a specific magical tradition. In relation to this view, (techno)magic leaves open the question of interweaving specific cultural practices into its understanding of ‘magic’. At the moment, (techno)magic, while taking the considerations we outlined above on board, leaves open the question of interweaving a specific cultural practice of magic. This is an unresolved tension that we reserve as a potential task for future research. Our address to the (techno)magical primarily deals with the messy practice of post-digital culture inheriting from Western modernity, focusing on ethics of relationality as understood by feminist technoscience as ethics that operationalise the terms of labour, embodied experience and care.

The reasons are twofold: first, we are wary of positioning these systems of knowledge as ready-made solutions: indigenous knowledge is not an instrument of care for the Western world. Rebuilding relations of care requires attention to the material and embodied worlds within existing epistemologies. see decolonial epistemologies. Secondly, in the context of existing media art and resistant tech practices, the ideas of 'magic' come from very different lifeworlds. Some are employing specific vocabularies to describe technology, such as 'spells' or 'codebooks', while not necessarily practicing magic as traditionally understood (some members of varia and syster server collectives). Some directly draw on the existing witchcraft practices (Cy X, a Multimedia Cyber Witch, or Lucile Olympe Haute, artist and author of Cyberwitches Manifesto). The International Festival of Technoshamanism in Brazil unites practitioners who integrate computation, software and hardware into existing systems of belief by techno-mediating rituals and approaching technological artefacts as magical tools, beings or effigies. Following this, if there is a specific tradition of magic to draw upon, there is also a multiplicity of potential (techno)magics, each requiring an exploration of the situated knowledge systems and ethical positions of people who adopt them. What becomes important in the context of the current article is considering how these multiple positions plug into the existing Western epistemics, and how the disruption of the dominant knowledge systems takes place.

Care, Feminist Technoscience and (Techno)magic as Relational Ethics

When we refute the idea of ‘innocence’ contained in non-Western lifeworlds (and, therefore, in their magical traditions), we encounter the acts of belief in the world of Western tech in their own granular and messy context. What we call technology does not preclude non-instrumental relations to the world, and is sometimes directly contingent on unarticulated acts of belief. For example, this happens in places where belief is justified by one or another accepted reason, be it a case of cryptocurrency exchange or a Shintoist robot priest. In the former, it is a pre-approved belief in the fluctuations of value that upholds the existence of the crypto-market; and in the latter, it is the established religious practice that paves the way for technology to be accepted. Similarly, acts of belief are encountered where care is monetised, such as in toys Ai-Bo or Tamagochi, or in the medical field (where care is a valuable resource that can be outsourced to robots). If we let go of these commodified types of belief, what prevents us from making new relations of care outside of the boundaries drawn by techno-capitalism? Lucille Olympe Haute in Cyberwitches Manifesto, for instance, foregrounds magic as a practice of resistance grounded in feminist ethics. She writes about technology and magic without hierarchical distinction:

Let's use social networks to gather in spiritual and political rituals. Let's use smartphones and tarot cards to connect to spirits. Let's manufacture DIY devices to listen to invisible worlds (n.p.).

In the ethos of this manifesto, technology is liberated from the burden of being rational and therefore is reinscribed back into the realm of ethico-political practice. What other practices can we think of that would allow us to inscribe relationality of care into the current technological landscape?

We imagine (techno)magic as a materially embedded and embodied feminist practice that starts from a point in which non-humans, including machines, are not outside of the normative human-to-human relationality. This calls also for the rethinking of the role that non-humans play in it. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa explores this in her book Matters of Care. She calls for deeper integration of the concept of care into the relational and material consideration of the world:

Care is everything that is done (rather than everything that ‘we’ do) to maintain, continue, and re-pair ‘the world’ so that all (rather than ‘we’) can live in it as well as possible. That world includes… all that we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web (modified from Tronto 1993, 103) (161).

She follows Bruno Latour in underlining that human existence is not dependent and deeply interwoven solely with humans, but rather on many others, including technological things. Latour calls for turning away from “matters of fact” and to “matters of concern” as a resolution of the issue of taking “facts” for granted and therefore voiding the relations with these matters of political urgency. Puig de la Bellacasa then suggests a productive critique of escalating “matters of concern” further as “matters of care,” ”in a life world (bios) where technosciences and naturecultures are inseparably entangled, their overall sustainability and inherent qualities being largely dependent upon the extent and doings of care” (Brons, n.p.).

Turning towards specific entanglements produced by artists, we can consider another ritualistic artwork that reframes technology in relation to belief systems. Omsk Social Club uses LARPing (Live Action Role Play) as a way to create “states that could potentially be fiction or a yet unlived reality” (Omsk Social Club). In each work, a future scenario functions “as a form of post-political entertainment, in an attempt to shadow-play politics until the game ruptures the surface we now know as life” (Omsk Social Club). Some of the themes they explore include rave culture, survivalism, desire and positive trolling. The work S.M.I2.L.E. bears particular interest as a “mystic grassroot” ceremony (Omsk Social Club) that explores freedom from protocols of quantification and efficiency in the age of technological precision. The work starts with each user giving up one of their 5 core senses to engage in synesthetic experiences and reach other states of sensing. The work is, at the same time, a critique of the communities that gather around eco-technological innovation, and a spiritual ceremonial practice through which users are exploring synesthetic acts including being blindfolded, fasting and dancing. These allow users to engage with the LARP structure as a ritual that critiques neopagan constructions for their lack of reflexivity and suggests a local politics of being, interacting, sensing and playing.

It is important to note that the word “users” is chosen by Omsk Social Club to underline the role of the ceremony as a quasi-technology or software for the participants to make use of: the work reactivates machine-human relations as politically engaged and embodied ritual experiences. Omsk Social Club often works outside or between frameworks set by art institutions, engaging with spaces such as raves or the office space of a museum - institutional infrastructures outside of the “white cube”. In doing so, they also reinscribe the format of LARP in the context of art and technology infrastructures, producing critical meaning through the embodied interaction of the players/users. As Chloe Germaine notes, LARP is distinct from other modes of playing in how it prioritises the embodied immersion and “inhabiting both position of ‘I’ and ‘They’ as player-character negotiations” (Germaine 3). Furthermore, Germaine underlines how the “magic circle”, or limits of what is considered an in-game place and what is “out of character area”, allows the players to “hack and transform identities and social relationships” (Germaine 3). In Omsk Social Club’s, “creating a drift between body and mind” (Anikina, Keskintepe) is an important part of the ritualised engagement. LARPing is a kind of “open source magic” and a “theatre for the unconscious” in that it allows the users to get an embodied experience of technology (including the technology of their own body) and practice and experience new political positions (Anikina, Keskintepe).

By way of conclusion: Spirit tactics and aesthetics for anthropocene

Choosing to care actively is the starting point of considering (techno)magic as relational ethics and embodied epistemic practice. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from libertarian, commodified, power-hungry, toxic, conquering forms of belief and knowledge, and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine. Part of becoming-familiar means letting go of human exceptionalism to an extent: becoming on the scale that, in current theoretical thinking, extends to being posthuman or even ahuman (as Patricia McCormack suggests). Crucially, this perspective means entangling the technological into what could be called “media-nature-culture”, bringing about a “qualitative shift in methods, collaborative ethics and, (…), relational openness” (Braidotti 155). It suggests a material and embedded form of thinking, which increases the capacity to recognize the diverse and plural form of being. Recognising technological mediation, synthetic biology and digital life leads to the emergence of different subjects of inquiry, non-humans as well as humans as knowledge collaborators (Braidotti).

While (techno)magic does often involve particular surface-level aesthetics, and artists working with such contexts often utilise ‘alien’ logos and fonts (OMSK Social Club), diagrams (Suzanne Treister) or sigil-like imagery (Joey Holder), the question of aesthetics goes beyond symbolic relations. In line with media-nature-cultural understanding, aesthetics should be seen, primarily, as aisthesis, as the realm of the sensible and its distribution (Ranciére), most urgently in relation to the suffering brought by the climate emergency, experienced unevenly across the planet. It also needs to refute universalism by seeing the media landscape as uneven and diverse, following a call for Patchy Anthropocene in order to disentangle from the flattening terms of Anthropocene, such as “planetary” (Tsing, Mathews, Bubandt). The idea of a patch, they explain, is borrowed from landscape ecology that understands all landscapes as necessarily entangled within broader matrices of human and nonhuman ecologies.

Speculatively, and trying not to create any more new terms, we might want to designate a kind of spirit tactics for image politics in the Anthropocene discourse, as it requires engagement with images as apparitions of capitalism: acknowledging symbolic power and complications of representation, yet focusing on data structures, on the operational images and infrastructural politics of collective thinking and action. Here, perhaps, a note on the two distinct interpretations of the word 'spirit' is in order: first, understood as 'willpower' or inner determination. Secondly, 'spirit' can refer to the supernatural forces figured as beings or entities that are therefore able to participate in political life and in rituals that activate systems of belief. In other words, we can consider spirit tactics as a proposition for a form of political determination to be actualised within (techno)magic, be it images, alternative imaginaries, portals, diagrams and operationalised ways of embodied thinking (rituals).

(Techno)magic asks for the emergence of layered tactics of image production that allow both for the processes of figuration and the underlying 'invisuality' of what is being figured (e.g. data). Ian Cheng’s work Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (2022), an animation produced in a Unity game engine, presents an interesting consideration for the figuration of technological entities (or even spirits). The work offers a future imaginary of a techno-psycho-spiritual augmentation in a world where “AI entities are permitted to co-inhabit human minds” (Cheng). BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018-2019), as the AI system is called, is integrated with the human nervous system. BOB is meant to become a “destiny coach”, acting as a simulation, modelling and advising system that guides humans to probabilistically calculated outcomes during their lifetime.

The protagonist of the film is Chalice Wong - the daughter of the scientist responsible for BOB’s development and the first test subject, augmented with BOB since her birth. BOB and Chalice are bound by a contract that allows BOB to take control of life versions of Chalice in order to lead her down to the best possible life path. Yet as the film progresses, Chalice is depicted as increasingly alienated and discontent as BOB’s quest for the ideal path of self-actualisation takes over her destiny. She gradually becomes a prosthesis for the AI system. Chalice’s father considers “parenting as programming”, but he also treats his daughter’s fate as an experiment to develop BOB into a commercial product. The animation style, colourful, chaotic and glitchy, which is typical for Ian Cheng’s work, does well to represent both the endless variations of the future that BOB calculates in order to secure the best possible one and the hallucinatory moments of Chalice’s consciousness-jumping between her own self and BOB, entangling and disentangling with and from her technological double.

How do we figure our futures from the inside of the capitalist condition in the Anthropocene? Life After BOB: The Chalice Study can be seen as a dark speculation on the instrumentalisation of the human 'connectedness' to the world, a gamified version where human’s worth is measured on the scale stretching from failure to success to self-actualise. The spiritual aspects of Chalice’s journey are shown as completely commercialised: fate, destiny, and willpower are all presented as part of a cognitive product that sees the human body as the latest entity to capitalise on.

One particular aspect of Life After BOB: The Chalice Study is significant for questioning the tactics of visualisation. As the work is completed in the game engine, a lot of the underlying data structure for the animation is not hand-coded but is operationalised through various shortcuts that are usually used in game design. These include light, movement, and glitchy interactions of various objects. Ian Cheng notes that making animation in a game engine is more like creating software, allowing for fast production of iterations of the scenes (Nahari). Furthermore, the prequel to this work, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), was a live simulation of BOB displayed in a gallery as an artificial life entity that could be interacted with. These procedural aspects of visualisation introduce a consideration of underlying processes: even though Life After BOB: The Chalice Study is a recorded animation and not a live simulation like Ian Cheng’s previous works (the Emissary trilogy), the feel of images being driven by computational processes rather than manual aesthetic choices is still retained. In this sense, and also in the narrative choices of a human child augmented by an AI spirit, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study presents interesting considerations for the visuality of (techno)magic as a kind of combinatorial aesthetic figuration that unfolds between the figuration and its underlying infrastructure.

Contemporary technospirits such as Alexas, Siris, Tays and others are not so removed from the imaginary of BOBs. Algorithmic agents, bots and other figured entities participate in the world of aesthetic transactions spun across real and virtual worlds, engaging in relational processes with humans, including a range of interactions and affects. This could be seen in the spirit of procedural animism that ‘emerges exactly as figural tactics; it attends to the “aliveness” with which the algorithmic agents and other figured AIs participate in the contemporary life as represented (and, therefore, as lived, at least in terms of image economy), yet designated to play particular roles within neoliberal structures’ (Anikina 147). The process of figuration can be deployed to different political motivations: the (techno)magical approach would call for alternative figurations, technospirits that enable other environmental, political and cultural futures.

Another tentative tactic that we suggest for this as co-authors of this paper and as a collective is diagrammatic thinking. A diagram, as we see it, can be critical, operative and performative. It can actualise connections and lines of action. A diagram does not represent, but maps out possibilities; a diagram is a display of relations as pure functions. More importantly, a diagram can enable various scaling of possibilities: from individual tactics to mapping out collective action and to infrastructural operation. K Allado-McDowell employs diagrams in Air Age Blueprint. They comment: the task at hand “is not just ecological science but ecology in thought: how do we construct an image of nature with thought - not through representation or translation, but somehow held in the mind in its own right?” (73).

Artist Suzanne Treister maps diagrammatic thinking in Technoshamanic Systems (2020–21). Technoshamanic Systems “presents technovisionary non-colonialist plans towards a techno-spiritual imaginary of alternative visions of survival on earth and inhabitation of the cosmos … [and] encourages an ethical unification of art, spirituality, science and technology through hypnotic visions of our potential communal futures on earth” (Treister). The diagrammatic nodes of Treister’s work underline various forgotten and 'discredited' lines of knowledge, putting together alternative structures that extend both into the genealogy of knowledge and into the potential versions of the contemporary and of the future. In doing so, it achieves a kind of epistemic restoration by implying that these nodes belong to the same planes, categories, surfaces and levels of consideration - a move opposite to epistemic violence and hegemonic narratives.

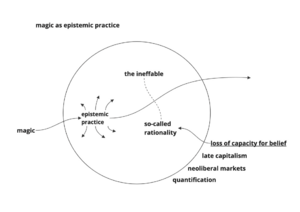

Figure 1 is a diagram drawn by us that represents the role of magic as an epistemic practice in relation to the embodied interaction of individuals (primarily Western subjects) through the world of late techno-capitalism. They can engage with magic (or (techno)magical rituals) as a relational and embodied epistemic practice; yet what they also face, within the Western epistemic, is an overall loss of capacity for belief, fueled by neoliberal markets and datafication. In this epistemic journey, they have to negotiate the pressure of so-called rationality and the inevitable presence of the ineffable, which can be also very normatively interpreted and captured in the form of popular entertainment, traditional belief systems and even random, sub-individual algorithmicised affects of image flows and audiovisual platforms such as TikTok.

Within the (techno)magical consideration, many various diagrams are possible. The aim behind them is not to stabilise, but to make visible and to multiply alternatives. However, this is just one of many potential “spirit tactics”: our ultimate proposition is to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice. We appeal to a tentative future: thought becoming operationalised as we engage in thinking-with diagrams and use diagrams as rituals-demarcated-in-space; finding solidarity with our dead - ancestors, but also crude oil - in the face of the Anthropocene; rituals against forgetting; worlding and making technospirits.

Notes

- ↑ And similar paragraphs referring to recent exhibitions can be found in the earlier collections of academic writing; see, for example, “The Machine and the Ghost” (2013).

- ↑ Here, the public presentation is important for the context, so the invention of photograms by Fox Talbot in Britain in 1834 can be omitted.

- ↑ It is not by chance that when this paper was proposed, in the process of development, to the NECS 2023 conference dedicated to the topic of “Care”, it was allocated in the panel “Media, Technology and the Supernatural”.

- ↑ Entheogen means a psychoactive, hallucinogenic substance or preparation, especially when derived from plants or fungi and used in religious, spiritual, or ritualistic contexts.

Works cited

Allado-McDowell. K. Air Age Blueprint. Ignota Books, 2023.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Geoff Cox. "Toward a Minor Tech". A Peer-Reviewed Newspaper, edited by Christian Andersen and Geoff Cox, vol. 12, no. 1, Apr. 2023, p. 1.

Anikina, Alexandra. "Procedural Animism: The Trouble of Imagining a (Socialist) AI". A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, vol. 11, no. 1, Oct. 2022, pp. 134–51.

Anikina, Alexandra, and Yasemin Keskintepe. Personal conversation with Omsk Social Club. 2 Feb. 2023.

Appadurai, Arjun. "Afterword: The Dreamwork of Capitalism". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, vol. 35, no. 3, 2015, pp. 481–85.

Arns, Inke. "Deep Talk Technoschamanismus". Kaput - Magazin Für Insolvenz & Pop, 5 Dec. 2021, https://kaput-mag.com/catch_en/deep-talk-technoschamanism-i_inke-arns_videoeditorial_how-does-it-happen-that-in-the-most-diverse-places-artists-deal-with-neo-shamanistic-practices/.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, 2007.

Braidotti, Rosi. Posthuman Knowledge. John Wiley, 2019.

Brons, Richard. "Reframing Care – Reading María Puig de La Bellacasa 'Matters of Care Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds'". Ethics of Care, 9 Apr. 2019, https://ethicsofcare.org/reframing-care-reading-maria-puig-de-la-bellacasa-matters-of-care-speculative-ethics-in-more-than-human-worlds/.

Campagna, Federico. Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

Cheng, Ian. Life After BOB: The Chalice Study. Film, 2022, https://lifeafterbob.io/.

Choy, Ka Fai. Tragic Spirits. Audio-visual performance, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lOTOn0WtaFA&ab_channel=CosmicWander%E7%A5%9E%E6%A8%82%E4%B9%A9.

Chéroux, Clément, et al. The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult. Yale University Press, 2005.

Clarke, Arthur C. Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. Harper & Row, 1973.

de la Bellacasa, María Puig. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. Zero Books, 2009.

Germaine, Chloe. "The Magic Circle as Occult Technology". Analog Game Studies, vol. 9, no. 4, 2022, https://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/631195/3/The%20Magic%20Circle%20as%20Occult%20Technology%20Draft%203%203-10-22.pdf.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Huhtamo, Erkki. "Natural Magic: A Short Cultural History of Moving Images". The Routledge Companion to Film History, edited by William Guynn, Routledge, 2010.

Latour, Bruno. "Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern". Critical Inquiry, vol. 30, no. 2, Jan. 2004, pp. 225–48.

MacCormack, Patricia. The Ahuman Manifesto: Activism for the End of the Anthropocene. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Mays, Sas, and Matheson, Neil. The Machine and the Ghost: Technology and Spiritualism in Nineteenth- to Twenty-First-Century Art and Culture. Manchester University Press, 2013.

Nahari, Ido. "Empathy Is an Open Circuit: An Interview with Ian Cheng". Spike Art Magazine, 9 Sept. 2022, https://www.spikeartmagazine.com/?q=articles/empathy-open-circuit-interview-ian-cheng.

Olympe Haute, Lucile. "Cyberwitches Manifesto". Cyberwitches Manifesto, 2019, https://lucilehaute.fr/cyberwitches-manifesto/2019-FEMeeting.html.

OMSK Social Club. S.M.I2.L.E.. Volksbühne Berlin, 2019, https://www.omsksocial.club/smi2le.html.

Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Duke University Press, 2000.

Treister, Suzanne. Technoshamanic Systems. Diagrams, 2021-2022, https://www.suzannetreister.net/TechnoShamanicSystems/menu.html.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, et al. "Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology: An Introduction to Supplement 20". Current Anthropology, vol. 60, no. S20, Aug. 2019, pp. S186–97.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. "On Models and Examples: Engineers and Bricoleurs in the Anthropocene". Current Anthropology, vol. 60, no. S20, Aug. 2019, pp. S296–308.

Whitechapel Gallery. "Magic: Documents of Contemporary Art". YouTube, 2021, September 18, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUOYhzZkxwk&ab_channel=WhitechapelGallery.