Pdf:Toward a Minor Tech: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<h1 class="outline">Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software</h1> | <h1 class="outline" id="h1-p8-a">Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software</h1> | ||

<div class="item" id="item-p8-a"> | <div class="item" id="item-p8-a"> | ||

Revision as of 11:18, 20 January 2023

Contributors

Christian Ulrik Andersen, Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, is attempting to bring the knowledge and practices of digital culture and art to the fore.

Geoff Cox is Professor of Art and Computational Culture at London South Bank University, and co-director of Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (CSNI), working across software studies and contemporary aesthetics.

Camille Crichlow is a PhD Researcher at the Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Racism and Racialisation (University College London). Her research interrogates how the historical and socio-cultural narrative of race manifests in contemporary algorithmic technologies.

Mateus Domingos is an artist and MRes researcher at CSNI, London South Bank University.

From a network of Feminist Servers the following authors contributed: mara karagianni - artist, software developer, sysadmin, ooooo - Transuniversal constellation, nate wessalowski - PhD student at Münster University, vo ezn - sound && infrastructure artist.

Teodora Sinziana Fartan is an artist and PhD researcher at CSNI, London South Bank University.

Susanne Förster is a PhD candidate and research associate at the University of Siegen. Her work deals with imaginaries and infrastructures of conversational artificial agents.

Inte Gloerich (Utrecht University & Institute of Network Cultures) researches sociotechnical imaginaries around blockchain technology as they appear in for instance memes, startup culture, and art.

Daniel Chávez Heras is Lecturer in Digital Culture and Creative Computing at King's College London. He studies the computational production and analysis of visual culture.

Macon Holt is a a Post-Doctoral researcher at Copenhagen Business School. He is author of 'Pop Muisc and Hip Ennui. A Sonic Fiction of Capitalist Realism' (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Jung-Ah Kim is a PhD researcher in Screen Cultures and Curatorial Studies at Queen’s University. She studies the relationship between weaving and computing and traditional Korean textiles.

Edoardo Lomi is a PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School. His project focuses on the palliative care of digital infrastructures.

Inga Luchs is a PhD candidate at the University of Groningen. In her research, she deals with questions of data classification and discrimination from a cultural and technical perspective.

Gabriel Menotti is Associate Professor in Film & Media at Queen's University and an independent curator, and co-cordinates the Besides the Screen network.

Alasdair Milne is a PhD researcher with Serpentine Galleries’ Creative AI Lab and King’s College London. His work focuses on the collaborative systems that emerge around new technologies.

Anna Mladentseva is a PhD researcher at University College London whose project focuses on the conservation of software-based works of art and design from the Victoria & Albert museum.

Shusha Niederberger is a PhD researcher based at Zurich University of the Arts and working on user subject positions in datafied environments and aesthetic strategies of using otherwise.

Søren Bro Pold Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, works with the arts of the interface and interface criticism.

Roel Roscam Abbing is a PhD researcher in Interaction Design at Malmö University's School of Arts and Communication. There he studies alternative and federated social media systems.

Winnie Soon is a Hong Kong-born artist coder and researcher, engaging with themes such as Free and Open Source Culture, Coding Otherwise, artistic/technical manuals and digital censorship.

Magdalena Tyżlik-Carver ferments data and investigates Critical Data and related practices through curating. She is Associate Professor in Digital Design and Information Studies at Aarhus University.

Varia is a space for developing collective approaches to everyday technology. https://varia.zone

Jack Wilson is a PhD researcher at the University of Warwick’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies. He is not a conspiracy theorist.

xenodata co-operative investigates image politics, algorithmic culture and technological conditions of knowledge production and governance through art and media practices. The collective is run by curator Yasemin Keskintepe and artist-researcher Alexandra (Sasha) Anikina.

Sandy Di Yu is a PhD researcher at the University of Sussex and co-managing editor of DiSCo Journal (www.discojournal.com), using digital artist critique to examine shifting experiences of time.

Freja Kir is researching across intersections of artistic methods, spatial publishing and digital media environments. Creatively directing fanfare – collective for visual communication. Contributing to stanza – studio for critical publishing. PhD researcher, University of West London.

Camille Crichlow title

Camille Crichlow text

Teodora Sinziana Fartan title

Rendering Minor Worlds

Teodora Sinziana Fartan

Critical renderings of speculative virtual imaginaries are increasingly emerging today as a form of collective utterance, a minority language that responds to the current states of emergency that we find ourselves in socially, politically, ecologically and technologically. The recent crystallization of immersive worlding as an experiential storytelling practice situates itself within the political context of resistance through its search for modes of being-otherwise. Kafka writes of literature that it should “affect us like a disaster, that grieves us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone”, foregrounding the affective and transformative power of storytelling - stretching forwards from his time to the present day, we see this practice of critical storytelling extended into the realm of virtual ecologies with artists like Ian Cheng, Lawrence Lek, David Blandy and Larry Achiampong, Sahej Rahal and Keiken formulating critiques of our contemporary context by producing minor worlds that speculatively explore alternative narratives. As Stengers urges us, these practices attempt to imagine “connections with new powers of acting, feeling, imagining, and thinking” and then prototype, hack, develop and render these into being.

A question, therefore emerges: how can we position and conceptualize these novel modes of expression that operate within the scales of virtual game spaces and their underlying networks of exchange? How can practices of worlding enable us to abandon “habitual temporalities and modes of being”, as Helen Palmer puts it, and think beyond ourselves, speculatively, towards possible futures and fictions?

The turn towards immersive world design is enabled by the recent deployment of game engine technologies towards critical digital experimentation, enabling artists to produce increasingly complex digital artifacts. Similarly to the properties of a minor language formulated by Deleuze and Guattari in their analysis of Kafka’s writing, today’s turn towards the production of virtual worlds as sites of alternative possibilities is deterritorializing the existing entertainment-centric and economically-driven mode of existence of immersive game productions. Within the parameters of the game engine itself, the various features, interfaces and functionalities of mainstream game design software are geared towards competitive ludic productions. However, with the increased accessibility of gaming technologies, we see the emergence of collective efforts to utilize game engines critically, towards the production of minority worlds, where the entertainment-focused properties of commodified games are replaced with experimental assemblages and their affect constellations.

When the majority language of the game engine is deployed into the minor territories of experiment and social critique, the audience's connection to political immediacy is facilitated through the experimental readings that are enabled. Pushing beyond the transformation of given content into the appropriate forms expected of major literature, worlding moves into the territory of minority expressions, where experimental and non-linear formats operate in networked and multifaceted ways, “speaking first and only conceiving afterwards”, as McLean infers. This study, therefore, aims to trace the ways in which new openings into alternative imaginaries are made possible on the shores of virtual worlds: how do virtual ecologies allow for new ways of being and knowing? And through these new modes of existence, how can worlding promote a state of community and becoming, foregrounding active solidarities?

Jack Wilson title

Jack Wilson text

Susanne Förster title

Susanne Förster text

Blockchains otherwise

Blockchains otherwise

Inte Gloerich

Is resistance to blockchain-based marketisation possible? Activist and artistic engagements with blockchain technology point to (at least) four different, partially overlapping, tactics towards this aim. The first is part of an accelerationist logic: riding the waves of capital until capitalism finally crashes, funding alternative values with whatever profit was accrued while it lasted. As Jaya Klara Brekke puts it: “tap the end of capitalism for those funds you will need in order to build new worlds” (2022, 104). The artwork Terra0 could be an example of this logic. Connecting a forest to a blockchain, the project gives the forest agency to sell its logs and buy more land to expand itself (Seidler, Hampshire, and Kolling 2016). Economic growth logic inverted for a more bountiful nature.

The second tactic is part of prefigurative politics, which David Graeber describes as “the idea that the organizational form that an activist group takes should embody the kind of society we wish to create” (2013, 23). Building alternative blockchain systems that perform a different kind of politics and social organization could be an example of this. DisCO, a distributed cooperative organisation inspired by feminist economics, thinks about ways of making visible the value of care work in blockchain-inspired governance systems. DisCo does not settle for blockchain ‘as is’, but bends it to fit their values (Troncoso and Utratel 2019).

Then, there are those that explore how blockchain’s logics can be subverted to make space – however minor – for different ways of relating in non-financialised ways. To explore what this might mean, I've been inspired by Patricia de Vries’ take on “plot work as an artistic praxis” (2022) that builds on decolonial theorist Sylvia Wynter’s description of plots: small, imperfect corners of relative self-determination within the larger context of colonial plantations (1971). De Vries asks how artistic work, implicated as it is in institutional and capitalist logics, can perform plot work to create space for relating outside of those logics. A possible answer to this question comes from artist Sarah Friend, who programmed her Lifeforms NFTs in such a way that they ‘die’ if they are not cared for. The NFT has to be given away for free to someone else, who then takes over the caring responsibilities (2021). Lifeforms represent little plots of care relationships, not only to the NFT, but also to those around you, calling on others to ‘care for’ instead of ‘capitalize on’.

However, these tactics hinge on the assumption that blockchain is here to stay. Perhaps another tactic should also be explored: how to protect fragile life-sustaining elements against capture by blockchain’s market logics? A tentative example could be Ben Grosser’s Tokenize This, that creates “unique digital objects” in the form of a url that is only accessible once, and is deleted straight afterwards (2021). This project doesn’t protect anything against tokenisation necessarily, but it does create slippery objects difficult to grasp through tokens. Perhaps ephemerality in the context of purported immutability can be a fruitful lens for more work in this direction.

Edoardo Lomi & Macon Holt title

Edoardo Lomi & Macon Holt text

nate wessalowski & Mara Karagianni (Feminist Servers) title

nate wessalowski & Mara Karagianni (Feminist Servers) text

Shusha Niederberger title

Shusha Niederberger text

Jack Wilson title

Jack Wilson text

Roel Roscam Abbing title

But does it scale?

Roel Roscam Abbing

This is a terrible question common in technical circles to judge the merit of proposals and projects: can your idea expand in size to be relevant to many and, therefore, relevant at all? It is also often used as a way to put down alternative proposals, based on the implication that these proposals won’t scale and are therefore not worth pursuing further. Simultaneously, scalability is one of Silicon Valley’s core concerns as it enables the massive profits of social platforms.

Initially, I found myself avoiding the question of scalability, but due to recent developments I find myself compelled to consider it sincerely. Alternative digital infrastructures can engender different social relations than those of the scaled social platforms. However, if we are to build other systems that “mirror the world we want to see” and build actual prefigurative counter-powers (Keyes et al.) to platform capitalism, these alternatives, in one way or another, will need to operate at scale.

The negative externalities of scaled social platforms are becoming ever more evident, leading to an interest for non-scalability or other undoings of scale. This is expressed in the grassroots of computational culture (de Valk), as well as within human-computer interaction research literature (Larsen-Ledet et al.; Lampinen et al.). Over scalability, this literature suggests other metaphors such as proliferation as a way to consider the impact of a project.

The concerns against scalability are manifold. Anna Tsing demonstrates how scalability is a system's property “to expand without changing the nature of what it does”(Tsing, 2012, p. 8) and, as such, is fundamental to extractive capitalism. Consequently, scalability has the effect of erasing difference and local diversity, leaving ruins in its wake.

In response to Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter in 2022, millions looked to Mastodon. This social network differentiates from Twitter in that it is a part of a network of thousands of smaller and interconnected sites known as the Fediverse, itself not run by any single entity. In the months after the purchase, this has proven to be a scalable system, but one that scales differently. Thousands of new and self-sovereign social networks were set up and through federation to become a part of a larger network. Thus, rather than scaling a single platform vertically, the process saw a network of networks scaling horizontally (Zulli et al.).

As someone who co-administers one of those small social networks, the months during Musk’s takeover made the necessity of scalability as a design property of software acutely felt. Our little space had to grow substantially within a short period of time. Not for growth or profit, but to be able to accommodate friends in need.

Through a different scalability, but scalability, nonetheless, millions managed to explore an alternative to the platform model by joining and trying, if only briefly, another model. Had the software and the model not been scalable at that moment of urgency, it would have been dismissed straight away. Instead, through scalability, the ideas and the model started to proliferate beyond the originary technical communities, after almost two decades of being around but being dismissed. Now that the terrible question is answered, we can start collectively posing more interesting ones.

xenodata co-operative title

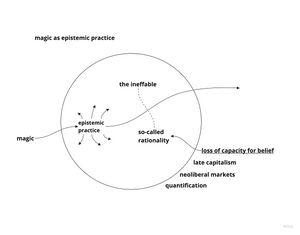

Spirit Tactics: (Techno)magic as Epistemic Practice

xenodata co-operative (Alexandra Anikina, Yasemin Keskintepe)

Speculative narratives of (techno)magic such as those offered by feminist technoscience, cyberwitches and techno-shamanism come from knowledge systems long marginalised in a hyper-optimised and hard-science-reliant capitalist discourse. Aiming to de-centre Western rational imaginaries of technology, they speak from alternative epistemic positions, decolonial and translocal perspectives. But what exactly does it mean to appeal to “magic” in the age of hegemonic Western epistemics? How do we deal with magic in the context of resistant tech practices?

Magic, as considered here, activates a different modality of the word “belief” than the commodified beliefs within capitalism. Rather, belief stands for a long-denied possibility of an alternative political imaginary (one that, as Mark Fisher suggests, is excluded within capitalist realism). Within this system, belief can only be exercised within the confines of certain institutions and framings: a church, a hospital, a rave, an art space. This is the core provocation of magic: it activates the systems of belief in spaces where they are not supposed to be activated.

Technology, in relation to magic, could also be liberated from being a despirited tool (a hammer), or from being a magic-wand type solution to the world’s problems; (techno)magic activates a reality-system of magic in certain space-times inside techno-capitalist infrastructures. At the same time, magic is not a universal solution to capitalism; it's not possible to exit into magic as some kind of an innocent primordial state. Magic is a granular, messy middle situated between sliding and not always matching scales of epistemic conditions, beliefs and politics.

(Techno)magic alters infrastructures, procedures and protocols, introducing the ineffable, 'that which cannot be captured by descriptive language, and which escapes all attempts to put it to "work"' (Campagna 10) - including not only human physical labour but also data put to work within statistical models. Yet, by animating the thought process, magic opens it to the possibility of the Other, and makes apparent the flows of (political) energy as an embodied experience. We understand (techno)magic as relational ethics + capacity to act beyond the constraints of the current capitalist belief system. (Techno)magic is about disentangling from libertarian, commodified, power-hungry, toxic, conquering forms of belief and knowledge; and instead cultivating solidarity, relationality, common spaces and trust with non-humans: becoming-familiar with the machine.

Artists do this by means of rituals: Choy Ka Fai weaves (motion capture) technology within shamanistic dance rituals in his audio-visual performance Tragic Spirits, and Omsk Social Club creates Live Action Role Plays (LARP)that introduce communal “states that could potentially be fiction or a yet unlived reality” (Omsk). Both facilitate a bodily encounter with the reality-system of magic, a transgression into imaginary politics and other worlds.

We propose to take magic seriously as an ethical and epistemic practice. We appeal to a tentative future: thought becoming operationalised as we engage in thinking-with diagrams and use diagrams as rituals-demarcated-in-space; finding solidarity with our dead - ancestors, but also crude oil - in the face of the Anthropocene; rituals against forgetting; making technospirits and conjuring worlds.

Shusha Niederberger title

Minor User: Subjectivity of small technology

Shusha Niederberger

After Elon Musk bought Twitter end of October 2022, people started discussing alternatives like Mastodon, a micro-blogging service like Twitter. In contrast, Mastodon is not corporate owned but a network of connected servers, often run by small collectives and non-profit organisations. During the following exodus of users, the Mastodon network grew from 5 to 9 million users and more significantly, from 3’700 to 17’000 servers (in contrast, Twitter has 238 million users). The migration to Mastodon thus is a movement trough technological scales, and from the users side, it was often experienced as a crisis in subjectivity.

The return of the server

One aspect in this crisis is the return of the server. On big technology platforms, servers have disappeared in favour of services, abstracted away from specific machines, local contexts and practices. We simply don’t know on how many servers Twitter is running. When Mastodon asks users to pick a server, it asks about a specific context to join, and in order to answer this, users need to identify themselves in different ways than on big technology platforms. Technological scale thus is linked to different ways of being a user.

User subject positions

„User“ is a general and very vague subject position offered to people participating in technological practice. Subject positions themselves are cultural imaginations (Goriunova 2021). They are role models or figurations, and offer a position in the world from which to make sense. They are not the same as individual subjectivity, they are shared and articulated in the cultural domain. As Goriunova insist, they are also aesthetic positions in the sense that they formulate a position from where practice is possible.

One example for thinking through how subject positions are invoked trough technology is formulated in The Wishlist for *TransFeminist Servers (2022), which is an actualisation of an older text, the Feminist Server Manifesto (2014).

Servers as protagonists

Both the Manifesto and the Wishlist choose the server as their protagonist, in the form of a self-articulation. A protagonist is what Goriunova calls a figure of thought that offers „a position from which a territory can be mapped and creatively produced“ (Goriunova 2021: 43).

At the center of this territory are questions of servitude: what does it mean to be served, or to serve? (Hofmüller et.al. 2014) This decenters notions of use-fullness and use-ability with their focus on functionality, efficiency, and scaleability that are markers of big technology’s abstraction, and introduce relations of care. The territory offered by the *TransFeminist Server thus is structured by affection, not extraction. Being part of a *TransFeminist Server means partaking in an ongoing negotiation of the conditions for serving and service. Use here is not an act of consumption, but of creation and re-creation.

Anna Mladentseva title

Anna Mladentseva text

Sandy Yu title

Feeling short on time? PhD Researcher claims it's because of digital optimisation

Sandy Di Yu

It’s me, I’m the researcher. And I’ve been running late for things all my life. I was born 10 days late, and then some decades later I was like, “why is everyone around me feeling like time has both stood still and disappeared?” It turns out there’s a load of people who have asked the same thing, people who are way smarter and more established, and those people have provided a myriad of interesting responses.

The most obvious answer to time scarcity lies in the hours of labour the average worker puts into her day. This is despite the fact that automation technologies have infiltrated every crevice of contemporary life (Crary, 2013: 40). The promise of emancipation from mundane work remains unfulfilled, mocking us as those same technologies produce ever more work or else commodify the small moments of respite in between.

The increase in work is a symptom of capitalistic growth, which necessitates accelerated productivity for its own survival. Yet since the use of digital platforms has become mainstream, the loss of time has reached a fever pitch. So the question then becomes, what is to be blamed for our current state of time scarcity: the managerial structure of our current socioeconomic system, or the development of digital technologies? Which came first and caused the other, the capitalist chicken or the technological egg?

While existing literature often points to both in equal measure, what is most striking is the inextricable ways in which digitality and management have become woven together in recent years. My hunch, thus, is that neither is solely culpable, for one wouldn't exist in its current form without the other. Instead, it is the logic of optimisation that enfolds both the systemic structure of digital technologies and the managerial framework of contemporary capitalism to cannibalistically exacerbate one another. Timescales thus become skewed such that time is paradoxically both negligible and infinite, due to processing speeds and the perceived perpetuity of digital media, respectively.

Optimisation might mean hiding the discrete units that necessitate digitality, making the metaphors of flow or stream into reality and predicated on the contrived synchronicity of micro-processes (Soon, 2016: 211). It could involve the trimming of code to fewer lines to achieve an aesthetic particular to “good” algorithms (Galloway, 2021:227). It could be following an unofficial but known set of rules in an attempt to get web pages in front of more viewers as with Search Engine Optimisation, or else squeezing every last drop of value from a data set (Halpern, 2022: 201).

Regardless of how it materialises, the logic of optimisation mirrors the mechanics of “progress”, a hangover from post-enlightenment sentiments that continues to plague the current state of socioeconomic affairs (Azoulay, 2019:21). Consequently, we are left with no future to work towards and no past for which to be liable, a perpetual present without time that we're somehow already late for.

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Colophon

A Peer-reviewed Newspaper

Volume 12, Issue 1, 2023.

Edited by all authors

Published by Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University

Organised in collaboration with Centre for the Study of the Networked Image, London South Bank University; King's College, London; transmediale, Berlin; Film & Media/FAS, Queen's University; and Varia, Rotterdam.

The publication was generated with wiki-to-print hosted on Creative Crowd, by Varia.

Publishing licence: CC4r - https://constantvzw.org/wefts/cc4r.en.html

Printing: Drukkerij Tripiti, Rotterdam. Printed in an edition of 2000 copies.

Design: Manetta Berends & Simon Browne (Varia) https://varia.zone

Fonts: All fonts used in this newspaper are published freely under the SIL Open Font License: https://scripts.sil.org/OFL, apart from Authentic Sans, which is published under the WTFPL: http://www.wtfpl.net/

- Authentic Sans

- Computer Modern

- Degheest Types

- Junicode Condensed

- Latitude

- Lucette

- Redaction

ISSN: 2245-7593 (Print)

ISSN: 2245-7607 (PDF)

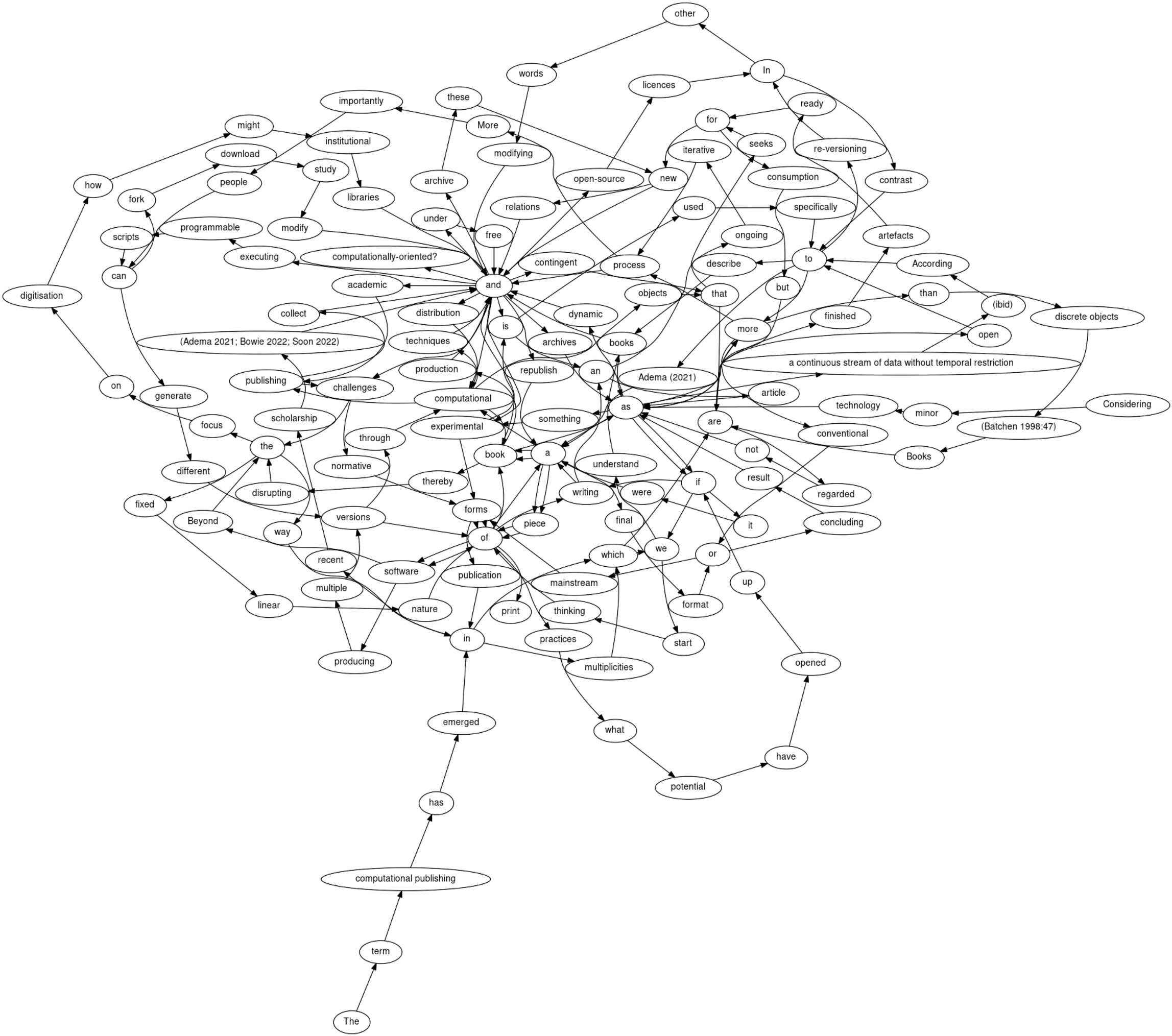

Writing a Book As If Writing a Piece of Software

Writing an Article as if Writing a Piece of Software

Winnie Soon

To generate the graph on the left, execute the following code in the terminal with Graphviz installed : dot -Tsvg tm_article.dot -o tm_article.svg

tm_article.dot:

digraph G {

graph[overlap=false, splines = true];

node[fontname="Hershey-Noailles-help-me"]

layout=neato;

The->term->"'computational publishing'"->has->emerged->in->recent->scholarship->"(Adema 2021; Bowie 2022; Soon 2022)"->and->is->used->specifically->to->describe->books->as->dynamic->and->computational->objects->that->are->open->to->"re-versioning"->In->contrast->to->more->conventional->or->mainstream->forms->of->book->production->and->distribution->computational->publishing->challenges->the->way->in->which->we->understand->books->and->archives->as->more->than->"'discrete objects'"-> "(Batchen 1998:47)"->Books->are->regarded->not->as->a->final->format->or->concluding->result->as->finished->artefacts->ready->for->consumption->but->as->"'a continuous stream of data without temporal restriction'"->"(ibid)"->According->to->"Adema (2021)"->a->computational->book->is->an->ongoing->iterative->process->More->importantly->people->can->fork->download->study->modify->and->republish->a->book->as->if->it->were->a->piece->of->software->producing->multiple->versions->through->computational->techniques->and->under->free->and->"open-source"->licences->In->other->words->modifying->and->executing->programmable->scripts->can->generate->different->versions->of->a->book->thereby->disrupting->the->fixed->linear->nature->of->print

Considering->minor->technology->as->something->experimental->and->contingent->that->seeks->for->new->relations->and->challenges->normative->forms->of->practices->what->potential->have->opened->up->if->we->start->thinking->of->writing->an->article->as->if->writing->a->piece->of->software->Beyond->the->focus->on->digitisation->how->might->institutional->libraries->and->academic->publishing->collect->and->archive->these->new->and->experimental->forms->publication->in->multiplicities->which->are->more->process->and->"computationally-oriented?"

}