Toward a Minor Tech:Kir5000: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Toward a Minor Tech]] | [[Category:Toward a Minor Tech]] | ||

[[Category:5000 words]] | [[Category:5000 words]] | ||

Revision as of 13:58, 8 June 2023

Glitchy, Caring, Tactical: A relational study between artistic tactics and Minor Tech

Introducing

As commercial digital platforms enable and constrain social action in various domains, their elusive structures increasingly govern spatially dispersed entities through digital devices, measurements, and registries (Ferrari & Graham, 2021). In order to critically engage with new developments at this scale, it is crucial to understand their drivers and, in this case, how resistant practices are helping to critically denote and substitute digital power structures.

In this paper, I trace and discuss the parameters of creative resistance to large-scale commercial digital platforms. With a contemporary focus, I draw on historical examples of creative counter-tactics and technological developments to address this tendency. By analyzing the participatory fileserver and artwork, VPN, I bring particular attention to the care, conditions, and drives of Minor Tech and creative works that mimic and critically display digital platform operations. What are the drives across creative resistance practices? And (how) do such creative contributions help to critically nuance various existing understandings of large-scale digital platforms?

The chapter is divided into six sections: Diving straight into the personal encounter with VPN, I first introduce the artistic case study that will unfold throughout the chapter; secondly, I include a historical, technological context, which supports the following third section of introducing the concept and notion of Minor Tech; in the fourth section I look to the doings of VPN through the objective of artistic tactical media; finally, the two last sections consider the drives of the projects and the aspect of care and maintenance present throughout the examples of the paper.

The insights to the case study draw on conversations with one-third of the collective artists behind VPN, Agustina Woodgate. The conversations were partly recorded and inspired by an open-ended format, allowing the topics to develop in unpredictable ways. These insights have been divided into sections throughout the paper to adapt a basic understanding of the relation between VPN and Minor Tech.

An emancipatory file server

Imagine a locally disrupted online platform: a scattered illustration turns up on your smartphone screen: the circular pattern turns into a globe, then an installation setting, and finally into the shape of a famous cartoon character, all happening along with a twisted interference of sounds and texts. Scattered letters start interfering with the scroll: “Nodes are elastic homes and links are dynamic roads, and each one is guiding you through a different story.” (VPN screen excerpt).

The scene unfolding describes the features of the emancipatory file server, VPN (Virtual PUB Network) (fig. 1). If reaching this screen intervention, you have reached the landing page and are physically near one of the nodes connected to the VPN installation. From this spot, all visitors have access to read and contribute to the growing archive of written, visual, and recorded content of the artwork and emancipatory fileserver, VPN.

My first personal encounter with VPN was when it served the purpose of mapping and archiving the graduation show of the independent Art and Design university Sandberg Instituut (Amsterdam) (2019). However, whereas archives typically help to create order, the visual interfaces of VPN were location-dependent and coded to intentionally disrupt the user’s scroll. Functioning as an open-source instrument, VPN was presented as a framework for circulating knowledge through shared visual, lingual, and vocal material.

During the graduation show, this format allowed the nodes to serve as a live feed, growing collective archive, and local navigational information service across four fixed nodes and one nomadic connected to the network. Technically, one node functioned as a server; the second was for the live feed; a third would capture sound; the fourth hosted visuals; and finally, the fifth one was for the text. Across these structures, a proxy had been installed to replace the content provided at each location. With each node installed in various locations, the interface would accordingly adopt and present the archive differently depending on the specific location.

While VPN is site-specific and activated through physical interaction, the VPN is simultaneously scalable and can be installed to work in any context. With a technical set-up that relies on servers of its host institution (in this case, the Sandberg Instituut), not only the IT department but the bureaucratic aspects of the internal academic digital network structures got challenged by the request to install the VPN. In this case, the existence of the VPN infrastructure likewise amplified the institutional digital infrastructure. Understanding infrastructures not only as systems for distribution but, more specifically, as promoters of socio-political, economic, and technological worlds enlighten how paying attention to both material and immaterial systems helps determine structures of behavior and patterns in digital realms (Berlant, 2016).

Although I dedicate specific attention to VPN, several recent artistic initiatives pursue like-minded, disobedient-action-driven research toward alternative narratives. Such initiatives are for instance exemplified by the critical collaborative artistic and academic research group, Possible Bodies, initiated by Helen Pritchard, Jara Rocha, and Femke Snelting. Their doings are focused on (but not limited to) the intersection of physical ground and digital sphere, which for instance, is the case in their Extended Trans*Feminist Rendering Program, initiating collective skills for sensing data and investigating contemporary scanning practices through magnetic resonance, ultrasound, and computer tomography. Another related collective example is the Cell for Digital Discomfort formed as a part of the 2021/2022 BAK fellowship for Situated Practices, which specifically looked into ways of refusing dominant digital platforms, referred to as “totalitarian innovation”. This focus stressed the solution-oriented approach of mono-cultural and corporate digital platforms with little (if any) room for investigating otherwise. Similar to these projects are their critical, collective knowledge that points to the hard realities of discriminating and data mining tech environments.

Chronological tech

To understand the involvement and drives of opposing and independent critical, creative tactics, I briefly turn to a rough outline of the web from its anonymous and hardly accessible shape to its seducing and omnipresent power structure of today.

When recently attending a debate at the Danish parliament on the critical influences of digital and artificial intelligence at work, the meeting was joined by people from various backgrounds; unions and think tanks, lawyers, doctors, software developers, teachers, and academics sharing observations on the influence of digital developments in everyday life. While opposing opinions were shared, most concerns were reappearing: the protection of data, the lack of democratic process pace to align with technological developments, and finally, a quest for independent initiatives, be it through academic networks, critical workshops, or critical creativity. Taking place in a European context, reasons such as GDPR, the expansion of chat GPT, and critical media coverage boosted by whistleblowing and leaked private data probably all played a role in leveraging such critical digital awareness. The experience was cheerful in that it reminded of engagement in critical digital action, which is otherwise mainly witnessed in academic and specific cultural contexts.

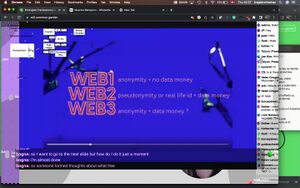

While web history has many layers, its differences can, as pointed to by Prof. Bogna Konior in her recent performative keynote lecture for the online conference Entangled Transparencies (2023), Center for Art and Media (ZKM), be simplified down to the drives for money, data, identity, and anonymity.

Naturally, looking into the history of the internet reflects more than money, data, and identity but also the development of technologies, ethics, and values. From being an exclusive site of military initiatives and favorable ways to proceed with academic research, Web 1.0 presented a system of static one-way interactions that, despite developing into a public domain, had limited bandwidth and user access (Curran, 2012; Lovink, 2002). With Web 2.0 (2004), the world wide web introduced a digital platform for user interaction. Web 2.0, with its myriad of tracking algorithms and commercial drives, presented us with automated profile generations and data-hungry thriving digital platforms across various fields (social media, search engines, shopping). In this context, networking services created a structure within which user-produced content could thrive and where online shopping boosted online money-making. In contrast to the financially driven hay-day giant platforms of Web 2.0, the introduction of Web 3.0 represented a web-based structure aimed at creating autonomous networks and increased privacy by implementing blockchain technologies and systems unchained from personalization. By proposing a cooperating solution, Web 3.0 exists as an alternative to the centralized structure of Internet 2.0 with its handful of dominant digital platforms (most notably Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft). However, while Web 3.0 was introduced nearly a decade ago, most digital platforms (and users) were shaped in the context of the world wide Web 2.0. Despite its decentralized mechanisms, Web 3.0 has not been adopted by most users but remains used by smaller, minor, counter-tech communities.

Minor Tech

In essence, the Internet is based on a protocol system. In general terms, protocols structure the relation, order, and chronology between all units embedded in the network. This approach arguably turns the accessible and readable code into a force of the movement. The development of Minor Tech draws links to organized protocols, conscious computing, and digital services that offer alternative platform usage. Minor Tech is often organized around, within, and through small communities of users and often overlaps with significant movements of copyleft, Free/Libre + Open Source Software.

Admittedly the notion of Minor Tech was unheard of to me before earlier in the year, contributing to the workshop Towards a Minor Tech organized by the Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus University, and the Centre for the Study of the Networked Image (LSBU). Before the workshop, I consulted a good friend and collaborator of mine with the intention of deepening my knowledge and discussing artistic practices concerning the topic. Instead, it turned out that the friend, too (active across various artistic and open-sourced initiatives and networks), needed to familiarize themselves with the notion of Minor Tech. While neither of us had come across the term before, the concept and values driving Minor Tech were familiar. When relating this paper to the topic of Minor Tech, this personal encounter seems relevant to mention, as I have come to realize that it also reflects a part of the nature of Minor Tech: firstly, that Minor Tech is (at the moment of writing) not known to the mass but to the dedicated minorities, and secondly, that Minor Tech reflects a set of values more than a methodological set of rules. While Minor Tech might be unfamiliar to the mass, examples of its existence are at the same time incredibly familiar in examples of digital commoning such as knowledge-sharing platforms and socializing services.

With a nod to the Damaged Earth Catalogue, initiated by Marloes de Valk, the concept of Minor Tech presents “small” tech solutions that operate at a human scale and are motivated by a drive for digital privacy, resource minimalism, environmental consciousness, and collaborative communities. Minor Tech presents solutions for everyday-platform navigation that do not involve commercial platforms and leans towards a DIY approach driven by a critical response to the current Web 2.0 corporate platform giants. As a kind of Minor Tech initiative in itself, the Damaged Earth Catalogue functions as an “evaluation and access device” for tracing actions and initiatives of collaborative and intimate counter-reactions to capital, commercial, and political power. While the movement of Minor Tech can be traced with a focus on political connotations, it is in the context of this paper, not so much the political theme that I draw on, but rather examples of the forms of the tactics in use that exploits, mimic, and reshapes existing online infrastructures in the quest of critical alternatives to corporate digital platforms.

Tactical tech

Despite the scattered illustrations mentioned in the first section, what makes the case study of VPN of interest is not so much the meaning of the content but the physically dependent disruption of it. Under regular conditions, a server remains static; however, due to the disrupted content of VPN, the server transformed into an active element of the experience. The artists describe these disrupting features to display both “strength and weakness” (VPN reader). Thereby when generating a visual interface across the different locations, VPN revealed the physical process of the infrastructural system. By revealing the doings of the VPN, the VPN tactic was likewise inviting the user to understand the making of its infrastructure. Tactical media is not a new interruptive genre to the web but has been explored by activists, journalists, artists, and academics across several contexts. With an overall drive towards possible socio-economical digital changes, Geert Lovink promptly researches critical artistic digital media practices as tactical media. Tactical media is, by Lovink considered as a term that “retain mobility and velocity and avoid the paralysis induced by the essentialist questioning of everything” (Lovink, 2002, p. 271). In other words, tactical media opposes passive users of commercial digital norms and actively contributes to critical understandings and alternative environments. Besides existing as a critical method for approaching digital media environments, the creative nature of tactical media also require or triggers imagination from makers and users by changing the course of expectations and navigation. This link between general digital interaction and preassumed space is well-researched as “algorithmic imaginaries” by media researcher, Taina Bucher, to describe how mental representations and speculations about the workings of digital algorithms nudge users’ behaviors, interactions, and navigation (Bucher, 2017). However, while Bucher focuses on social media mechanisms, the artistically provoked imagination makes possible limitless outcomes for the creative mind. With this in mind, VPN intentionally disrupts the anticipated user interaction and challenges the traditional ways we imagine and interact with everyday digital media.

VPN exemplifies a tendency in contemporary artistic production that intentionally (mis-)read, mimic, and replicate digital platform logic and behaviors through an artful inclusion of persons, space, and objects. However, it is difficult to deny that the most parasitic presence is not caused by minor or artistic counter-movements but rather by the large corporate digital platforms themselves – platforms that have the capacity to expand across digital activities, extract data and adjust algorithms for commercial intentions. Take Google, for example; being the most extensive digital search platform, Google presents itself as a company for search engine technologies, consumer electronics, and software. Meanwhile, the actual business model is based on advertising and data mining. As noted by John Durham Peeters, Google is of such an omnipresent scale that “For many, Google is the internet” (Peeters, 2015, p. 329). Similarly, the language and concepts of commoning practices, such as Minor Tech, are likewise misused and appropriated into capitalist systems (such as gift economy and digital management) (Federici, 2011).

Glitchy tech

As you move through the different VPN nodes, the content starts flickering. What in the previous location accumulated a stream of photos now provokes the activation of sound or moving images. At this point, the pace of the VPN interface has become more familiar, and the repetition of content disruption makes it possible to start detecting the interface influence of the work.

The critical inclusion of artistic practice becomes relevant when considering the user experience of VPN as moving away from the human as the sole emperor setting standards for digital measurements. With this in mind, the VPN allows us to consider how digital components are part of constructing the interface and how these occupy and create space, situate and guide their users. As such, the VPN pushes its users from knowing about the existence of an infrastructure to understand that infrastructure.

While the ability to perceive, analyze, and engage with material matter is central to critical humanistic studies, a posthumanist approach to VPN is relevant to critically consider its drives and intentions. The critical research by Olga Gorionuva specifically presents a study that crosses the disciplinary boundaries between software studies, artistic platforms, and cultural production online and questions the role of art in the context of the technological matter (Gorionova, 2006). While the technical posthumanism that Gorionova brings forth is introduced as a political tool for considering non-human species, it is useful to consider how the VPN presents and accumulates knowledge-sharing interventions as an attempt for renewed digital engagement. Considering the VPN from this approach sets an interesting example of how to reconfigure the meaning and understanding of specific technologies by introducing another social approach to the topic. From this position, the VPN suggests a twisted instrumentality as an alternative to data-centered automated services, allowing glitches and failure to produce reasoning.

As an ideological function, the commons broadly embraces a leftist opposition to private properties, capitalist systems, and the state. While the commons and shared goods arguably have been threatened by neoliberal and fixated levels of privatization, a reason for the popularity of the commons is also the drive for radical movements and alternatives to those capitalist models.

Despite being general in tone, this approach mainly refers to the commons in relation to land, natural resources, and related infrastructural systems - all material forms of commoning (Federici, 2011). Nevertheless, commoning aspects such as nonhierarchical organizing, collective decision-making processes, and rotation of leaderships (if any are needed), likewise apply to the collective work of Minor Tech, creative, and immaterial knowledge sharing.

Reading into the posthuman commons as defined by feminist scholar Braidotti stresses her approach to posthumanism as a necessary process of acknowledging the collective nature of the self in relation to the world (Braidotti, 2013). This attention follows in line with the idea that along with posthuman commons comes the ongoing determination to make transparent any mechanical transaction or connection before the creation of common relations (Braidotti, 2013).

Setting out to include posthumanism inevitably introduces an interdisciplinary lens that intersects both the material and immaterial. In the context of Minor Tech, posthuman commons are about unveiling technological structure through collaborative practice and doing so with skeptical awareness and the aim of discarding any hierarchical structures.

Caring tech

The technical complications of projects such as VPN exist of material limitations, from electricity plugs to internet connection. Starting as a software project, the VPN grew into a compilation of nodes, proxies, and hosting to eventually become a system of maintenance and care.

While the front-end presentation of VPN content seems distorted, the contributions of the VPN database were locally accumulated and made up of internal publishing initiatives across the Sandberg Institute. Ironically, the messy reality of the data-collecting process simultaneously worked as a cross-departmental knowledge-sharing of internal learnings. Effectively, as more and more people were using the VPN, the more it became about maintenance, accessibility, and care. While the scale of this task was unpredicted, it became clear from the conversations with Agustina that the VPN was set up to trigger consciousness about infrastructural activity or, as written in the VPN reader: “to explore the possibilities of autonomous infrastructures by building a zone of trust and situated knowledge as a form of ontological anarchism opposing itself to the platformization of Institutions.”.

To consider how knowledge commons (in this case, digital libraries) are generated and maintained, their subject positions are relevant in both interactions with humans and non-humans. To further address the nurturing labor and care that influence the artistic practices and Minor Tech communities, I draw inspiration from Gorionovas’ definition of the subject relevance for creative commoning knowledge sharing. Building on the notion of organizational aesthetics (as introduced in “Art Platforms and Cultural Production on the Internet” (2012)), Gorinova describes the subject as always in process and never complete.

Defining meta librarians, public custodians, general librarians, underground librarians, critical public pedagogues, multiform bibliographers, fancy general archivists, and cultural analysts, Gorinova covers the understated tasks of amateur historians and librarians, full-time book-scanners, publishing, digitizing books, and activating collections. Shadow librarians provide and caretake online free and open infrastructures that enable users to share and debate digital texts and collections (Gorionova, 2021; Marcell & Medak, 2019). Minor Tech practices inevitably fit into some of these ideas of shadow librarians and digital guardians of knowledge-sharing commons. Besides reminding of the Damaged Earth Catalog, several critical projects from the early digital era (such as the Whole Earth Catalog) resembles these roles of knowledge-sharing and caring structures. However, to concretize and reflect on the activities up close, I will detour to a personal encounter;

Next to his computer engineering duties, my dad fulfills the role of a guardian, custodian, and amateur historian of the critical and politically charged online Danish encyclopedia, leksikon.org. With a leksion motto that “doubt everything” and an About section that states how the encyclopedia is not, and does not, intend to be neutral, the tone is set…

Leksikon.org is a non-profit initiative run by volunteering engagement and initiated to produce an alternative narrative for those arriving from power positions. Leksikon.org dates back to an earlier era of digital knowledge sharing and predates the much more famous encyclopedia, Wikipedia (which did not register its domain before 2001). Leksikon.org draws inspiration from the Norwegian leftist publishing initiative PAX (1978-82) and is organized by a large number of contributors and translations of selected texts. While everyone can contribute, the submissions are filtered by smaller editorial groups of the organizing team. When scrolling through the different entries and the expansive country section (counting 247 entries), one inevitably stumbles on outdated spots, reflecting both how the process of updating such a project is immense and, at the same time also, the slower pace of caretaking that Leksion.org require. With my dad's background in computing and engineering, our home access to the internet was established in 1995; before this moment, the only possible connection had been limited to what was available on one server. My childhood is full of memories of my dad spending late night hours in front of a stationary computer in the corner of our living room, nourishing the encyclopedia, researching, translating, writing, and maintaining coding.

Initiatives such as Leksion.org constitute possibilities of disobeying classical history books and forming new subject positions from which new sociopolitical directions take form. The various tasks of ordering, converting, sorting, and transforming content to be accessible in cases like this become techno-cultural gestures and drive for knowledge sharing to a larger public.

While publishing content undoubtedly is a part of public-making, in the case of Minor Tech, the knowledge generation and sharing is produced and directed to minor small engaged publics. Borrowing from Michael Warners critical examination of the public, the conditions of possibilities for art in the public reminds us that counter-publics occur when there is little or no room for independent participation (Warner, 2005). Through caring and sharing communal structures, counter practices, in these cases, become tools that demonstrate knowledge as a process of public-making.

Conclusion

While we struggle to make sense of how corporate digital developments activate and direct, manipulate, and exhaust online environments - creative works show the potential to reveal such fabrics by visualizing, materializing, or simulating everyday software operations.

This writing presents artistic scenes unfolding in or around the peripheries of alternative artistic and technological practices. In this context, the VPN exemplifies a work that suggests how technical creative tactics may provoke interaction between the institution, the users, and their spatial surroundings. This kind of user interaction forms an analogy that makes us aware of the digital infrastructure and disrupts how most current corporate technology insists on smooth interaction that does not interrupt the experience. The VPN aims to downscale technology to a graspable level.

Ultimately, the VPN aims to downscale technology to a graspable level. Analyzing the VPN through the objective of Minor Tech lets us address large tech critically while learning about small-scale tech intimately.

Colophon

Berlant, L. (2016). The commons: Infrastructures for troubling times*, in Environment and Planning D:

Society and Space, University of Chicago, USA

Braidotti, R.& Hlavajova, M.(2018). Posthuman Glossary, Bloomsbury

Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society 20(1), 30-44.

Curran J. (2012). Rethinking internet history, Routledge

Federici, S. (2011) Feminism and the politics of the Commons. The Commoner. Available at: http:// journals.kent.ac.uk/index.php/feministsatlaw/article/view/32 (accessed 28 March 2016).

Gorionuva, O. (2006). Participatory Platforms and the Emergence of Art, in A Companion to Digital Art, ed. Christiane Paul, Wiley

Gorionova, O.(2021). Uploading Our Libraries: The Subjects of Art and Knowledge Commons, in Aesthetics of the Commons, Ed. Shusha Niederberger (ed.), Cornelia Sollfrank (ed.), Felix Stalder (ed.)

Lovink, G.(2002). Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture, Cambridge: MIT Press

Marcell, M. &Medak, T.(2019). Against innovation: Compromised institutional agency and acts of custodianship, Ephemera journal, volume 19(2): 345-368

Monteagudu, G.(2019). Women Reclaim the Commons: A Conversation with Silvia Federici, North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA ) | VOL. 51, NO. 3 — 256-261, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2019.1650505

Peeters, J. (2015). The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media, University of Chicago Press

Parisi, L.(2019) Media Ontology and Transcendental Instrumentality, Goldsmiths, University of London

Warner, M. (2005). Publics and Counterpublics, Zone Books, New York

Online conference. (2023). Entangled Transparency 3.0, ZKM, Karlsruhe, https://zkm.de/en/event/2023/03/entangled-transparency-30

VPN. (2019). Agustina Woodgate, Miquel Hervas Gomez, Sascha Krischock

Damaged Earth Catalogue. Marloes de Valk. https://damaged.bleu255.com/ Visited: March 2023

BAK Fellowship for Situated Practice (2021/2022), the Cell for Digital Discomfort—composed of Cristina Cochior, Karl Moubarak, and Jara Rocha, https://www.bakonline.org/prospections/on-digital-discomfort-editorial/#_ftn3

Possible Bodies. Jara Rocha, and Femke Snelting featuring Helen Pritchard. Extended Trans*Feminist Rendering Program (2020) with The Underground Division, London