Content Form:APRJA 13 Marie Dias: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary Tag: Manual revert |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

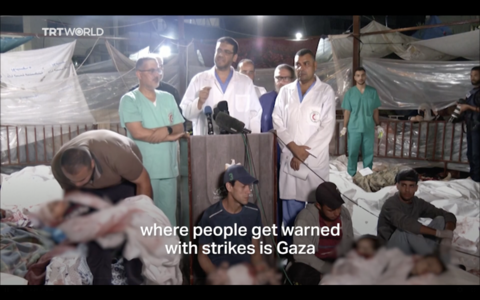

There is a video—or rather a pixelated, slightly blurry excerpt—circulating on social media. The video was originally a live-streamed press conference held by the Ministry of Health in Gaza in response to the airstrike that hit Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital on October 17, 2023, leaving hundreds dead and many more trapped under the rubble. The video and the screenshots that quickly circulated show members of the hospital’s medical staff gathered around a podium amidst the white-sheet-covered corpses of the explosion’s victims. Three to four men squat in front of the podium, holding the bodies of an uncovered baby and a partially covered young girl. Judging by the constrained distress on the men’s faces, they seem in disbelief over what they are holding. The shock of the situation is palpable, the men alternating between stiffly looking away and bowing their heads to face the dead children in their arms and on the ground before them. | There is a video—or rather a pixelated, slightly blurry excerpt—circulating on social media. The video was originally a live-streamed press conference held by the Ministry of Health in Gaza in response to the airstrike that hit Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital on October 17, 2023, leaving hundreds dead and many more trapped under the rubble. The video and the screenshots that quickly circulated show members of the hospital’s medical staff gathered around a podium amidst the white-sheet-covered corpses of the explosion’s victims. Three to four men squat in front of the podium, holding the bodies of an uncovered baby and a partially covered young girl. Judging by the constrained distress on the men’s faces, they seem in disbelief over what they are holding. The shock of the situation is palpable, the men alternating between stiffly looking away and bowing their heads to face the dead children in their arms and on the ground before them. | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_1.png|thumb|480px|Figure 1: Screenshot of the press conference-video]] | [[File:Marie_Image_1.png|thumb|480px|Figure 1: Screenshot of the press conference-video.]] | ||

Although the video was broadcast on several news channels, including the Arabic Al Jazeera, the uncut version is no longer available—neither in their archive nor on YouTube. However, screenshots and ultrashort excerpts of the video quickly circulated on platforms such as X, Instagram, and YouTube. In this way, it partakes in the “swarm circulation” that makes up today’s online information stream, which favors clips and screenshots over full-length videos, “previews rather than screenings” as the artist and critic Hito Steyerl formulates it (“In Defence” 7). At the time of writing this article, the video evidently exists solely as what Steyerl calls a “copy in motion”; as social media content, symptomatic of the ephemerality of the large amounts of images that circulate online today. The excerpt this paper refers to is a 17:21-minute-long version, posted on YouTube on October 18, 2023, the longest version that seems to still exist online (CasaInfo). | Although the video was broadcast on several news channels, including the Arabic Al Jazeera, the uncut version is no longer available—neither in their archive nor on YouTube. However, screenshots and ultrashort excerpts of the video quickly circulated on platforms such as X, Instagram, and YouTube. In this way, it partakes in the “swarm circulation” that makes up today’s online information stream, which favors clips and screenshots over full-length videos, “previews rather than screenings” as the artist and critic Hito Steyerl formulates it (“In Defence” 7). At the time of writing this article, the video evidently exists solely as what Steyerl calls a “copy in motion”; as social media content, symptomatic of the ephemerality of the large amounts of images that circulate online today. The excerpt this paper refers to is a 17:21-minute-long version, posted on YouTube on October 18, 2023, the longest version that seems to still exist online (CasaInfo). | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

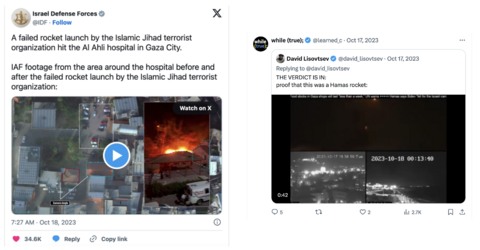

A paradigmatic instance of hyperaesthesia is the aftermath of the explosion at Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza when the internet instantly flooded with partisan reports, counternarratives, investigative articles, and X-posts comparing various ‘forensic’ image and video analyses. Palestinian officials immediately blamed Israel for what they called a “horrific massacre”; a statement subsequently contested by the IDF. As noted above, the battle to prove these contradictory narratives catalyzed an intense image war conducted through forensic image analysis online. Although the Israeli narrative around the explosion was largely contested, not only on social media but also by more well-credited agencies like Forensic Architecture and other preliminary investigative analyses, the hyperaesthesia of information muddied the perception of what was ‘real’ and ‘fake,’ making it impossible to distinguish propaganda from fact. | A paradigmatic instance of hyperaesthesia is the aftermath of the explosion at Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza when the internet instantly flooded with partisan reports, counternarratives, investigative articles, and X-posts comparing various ‘forensic’ image and video analyses. Palestinian officials immediately blamed Israel for what they called a “horrific massacre”; a statement subsequently contested by the IDF. As noted above, the battle to prove these contradictory narratives catalyzed an intense image war conducted through forensic image analysis online. Although the Israeli narrative around the explosion was largely contested, not only on social media but also by more well-credited agencies like Forensic Architecture and other preliminary investigative analyses, the hyperaesthesia of information muddied the perception of what was ‘real’ and ‘fake,’ making it impossible to distinguish propaganda from fact. | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_2 .png|thumb|480px|Figure 2: Examples of Israel’s narrative on X]] | [[File:Marie_Image_2 .png|thumb|480px|Figure 2: Examples of Israel’s narrative on X.]] | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_3 .png|thumb|480px|Figure 3: Examples of the Palestinian narrative on X]] | [[File:Marie_Image_3 .png|thumb|480px|Figure 3: Examples of the Palestinian narrative on X.]] | ||

As an example of this one could argue that, on the one hand, the Israeli government actively restricts media coverage of their war in Gaza in the manner that Baudrillard described for the Gulf War. For instance, most recently, Israel issued a ban on Al Jazeera and is, as the writing collective The Editors state, “targeting and killing photojournalists; because Israel has denied foreign journalists access to Gaza, with the exception of a few IDF-guided tours.” On the other hand, while this is impactful, today, imagery of the effects of war is not only available but ''unavoidable''. As is demonstrated in The Editors’ article ''Who Sees Gaza? | As an example of this one could argue that, on the one hand, the Israeli government actively restricts media coverage of their war in Gaza in the manner that Baudrillard described for the Gulf War. For instance, most recently, Israel issued a ban on Al Jazeera and is, as the writing collective The Editors state, “targeting and killing photojournalists; because Israel has denied foreign journalists access to Gaza, with the exception of a few IDF-guided tours.” On the other hand, while this is impactful, today, imagery of the effects of war is not only available but ''unavoidable''. As is demonstrated in The Editors’ article ''Who Sees Gaza? A Genocide in Images'', the mediatization of the war has evolved into a collective process of “sense-making,” in Fuller and Weizman’s terms, as the production and dissemination of images no longer accrue to the news media, but increasingly to the victims themselves: “the people of Gaza showed the world what the mainstream media could not: wounded civilians, leveled buildings, long lines of dead bodies wrapped in white sheets, bombed-out universities, bombed-out mosques, toddlers trembling in shock and covered in the grey, ashy dust of debris” (The Editors). Regardless of Israel’s restriction of media and press, the war takes place virtually before our eyes. In the words of lawyer Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, when presenting South Africa’s case against Israel at the International Court of Justice, it is “the first genocide in history where its victims are broadcasting their own destruction in real-time in the desperate, so far vain, hope that the world might do something” (The Editors). | ||

Gaza is thus an instance of overexposure to war today. In Baudrillard’s reading of the mediatization of the Gulf War, the focus was largely on what was ''not shown, not seen'' in a quest to maintain a certain level of support for the war. Today, the illusion linked to ''not seeing'' the horrors of the Gulf War has been replaced by a disillusionment caused by ''seeing too much'', eliciting a new type of skepticism towards the evidentiary value of images. While the political task then involved what could be called ''de-aestheticization'' by ''not showing'', the political task in warfare today is fundamentally a question of ''aestheticizing'', in the sense proposed by Fuller and Weizman; that is, making visible or “attuned to sensing” (33). | Gaza is thus an instance of overexposure to war today. In Baudrillard’s reading of the mediatization of the Gulf War, the focus was largely on what was ''not shown, not seen'' in a quest to maintain a certain level of support for the war. Today, the illusion linked to ''not seeing'' the horrors of the Gulf War has been replaced by a disillusionment caused by ''seeing too much'', eliciting a new type of skepticism towards the evidentiary value of images. While the political task then involved what could be called ''de-aestheticization'' by ''not showing'', the political task in warfare today is fundamentally a question of ''aestheticizing'', in the sense proposed by Fuller and Weizman; that is, making visible or “attuned to sensing” (33). | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

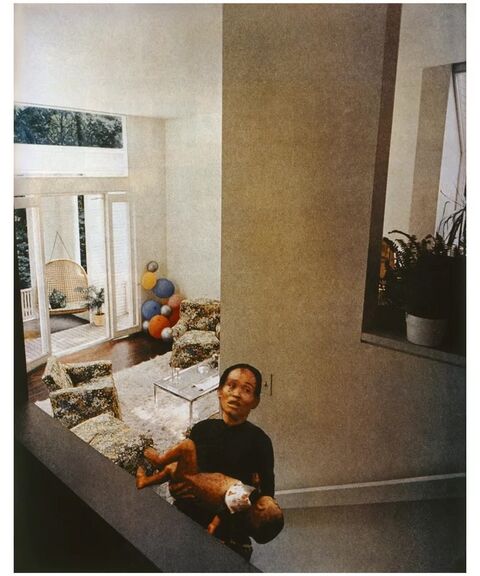

In her photomontage series ''House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home'' (1967–1972), Rosler combined photographs of wounded bodies from the Vietnam War with magazine cut-outs of flawless American living rooms. In rearranging the composition of elements, Rosler changed the frame of reference to perceiving the war, suggesting a skepticism toward its mediatization. The clash between two conflicting ''frames'' in her photomontages, the warzone, and everyday life, elicits a shock effect. | In her photomontage series ''House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home'' (1967–1972), Rosler combined photographs of wounded bodies from the Vietnam War with magazine cut-outs of flawless American living rooms. In rearranging the composition of elements, Rosler changed the frame of reference to perceiving the war, suggesting a skepticism toward its mediatization. The clash between two conflicting ''frames'' in her photomontages, the warzone, and everyday life, elicits a shock effect. | ||

[[File:Marie_image_4.jpg|thumb|480px|Figure 4: Martha Rosler "Balloons“, ca 1967-72, from the series: ''House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home.'' Copyright permission by Martha | [[File:Marie_image_4.jpg|thumb|480px|Figure 4: Martha Rosler "Balloons“, ca 1967-72, from the series: ''House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home.'' Copyright permission by Martha Rosler.]] | ||

In the Gaza video, however, the consolidation of the press conference frame and the warzone frame is not in itself shocking; rather, it is the way the latter has been choreographed, that stands out. While Rosler’s collages consisted of actual photographic elements, they were experienced through their context as artworks—overtly staged and manipulated as part of their methodology. In contrast, the video of the press conference in Gaza is not a post-processed artistic expression of the war, but a broadcast relayed live from the battlefield. While Rosler’s artworks make no evidentiary claim, the images in the video are first and foremost judged by what Sjöholm terms their “statements of fact.” | In the Gaza video, however, the consolidation of the press conference frame and the warzone frame is not in itself shocking; rather, it is the way the latter has been choreographed, that stands out. While Rosler’s collages consisted of actual photographic elements, they were experienced through their context as artworks—overtly staged and manipulated as part of their methodology. In contrast, the video of the press conference in Gaza is not a post-processed artistic expression of the war, but a broadcast relayed live from the battlefield. While Rosler’s artworks make no evidentiary claim, the images in the video are first and foremost judged by what Sjöholm terms their “statements of fact.” | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_5.png|thumb|480px|Figure 5: The frame zoomed in on the speakers]] | [[File:Marie_Image_5.png|thumb|480px|Figure 5: The frame zoomed in on the speakers.]] | ||

In one of the versions of the press conference video available online, the frame is initially zoomed in on the speakers at the podium, their faces serious as per the implicit protocol of a press conference of this gravity. The aesthetic logic here is similar to Rosler’s artworks: unremarkably staged. The spatial arrangement of the elements follows a pre-set scenography of expected components like bright lights, a stage with microphones, and men in authority-evoking clothes, hands crossed in front and constrained facial expressions. While this predefined ‘stagedness’ does not evoke any skepticism towards the factuality of the video, the zoom-out adds a second frame; that of a ‘staged’ warzone, revealing a ‘mass grave’ of dead bodies arranged around the podium, covered by white, blood-stained sheets (see Figure 1). This is where the perception of the video shifts and the mediatization of the war is highlighted by the aestheticized character of the crime scene, which can best be described as a scenography of war: staged to be seen in a certain way. The use of aesthetic strategies in this composition staged for the camera, meant to be seen, connotes a mediatization that exceeds merely representing the war. The staging of the bodies is unexpected, and the lack of spontaneity in their positioning in front of the camera breaks with the snapshot logic, stretching its boundaries. | In one of the versions of the press conference video available online, the frame is initially zoomed in on the speakers at the podium, their faces serious as per the implicit protocol of a press conference of this gravity. The aesthetic logic here is similar to Rosler’s artworks: unremarkably staged. The spatial arrangement of the elements follows a pre-set scenography of expected components like bright lights, a stage with microphones, and men in authority-evoking clothes, hands crossed in front and constrained facial expressions. While this predefined ‘stagedness’ does not evoke any skepticism towards the factuality of the video, the zoom-out adds a second frame; that of a ‘staged’ warzone, revealing a ‘mass grave’ of dead bodies arranged around the podium, covered by white, blood-stained sheets (see Figure 1). This is where the perception of the video shifts and the mediatization of the war is highlighted by the aestheticized character of the crime scene, which can best be described as a scenography of war: staged to be seen in a certain way. The use of aesthetic strategies in this composition staged for the camera, meant to be seen, connotes a mediatization that exceeds merely representing the war. The staging of the bodies is unexpected, and the lack of spontaneity in their positioning in front of the camera breaks with the snapshot logic, stretching its boundaries. | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

The unexpected frame of the re-arranged warzone somehow makes the viewer conscious of the mediatization of the events it depicts, as they are overtly ‘performed’ for the camera, an aesthetics notoriously linked with manipulation or propaganda. This evokes an initial suspicion towards the credibility of the video, raising Steyerl’s skepticism in ''Documentary Uncertainty'', “Is this really true?”. The very thought of practically preparing and arranging the podium and the bodies is absurd: Did the speakers straddle the dead bodies to reach the stage? Did someone yell “action” before livestreaming this macabre scene? One X-user captured the feeling of cautious skepticism that this clash of logics evokes, with the phrase “The most surreal zoom I’ve ever seen,” pinpointing how the staging of the warzone in a horrifying ''choreography of war'' breaks with the contract of the snapshot logic pertaining to ‘authentic’ evidentiary image practices today. | The unexpected frame of the re-arranged warzone somehow makes the viewer conscious of the mediatization of the events it depicts, as they are overtly ‘performed’ for the camera, an aesthetics notoriously linked with manipulation or propaganda. This evokes an initial suspicion towards the credibility of the video, raising Steyerl’s skepticism in ''Documentary Uncertainty'', “Is this really true?”. The very thought of practically preparing and arranging the podium and the bodies is absurd: Did the speakers straddle the dead bodies to reach the stage? Did someone yell “action” before livestreaming this macabre scene? One X-user captured the feeling of cautious skepticism that this clash of logics evokes, with the phrase “The most surreal zoom I’ve ever seen,” pinpointing how the staging of the warzone in a horrifying ''choreography of war'' breaks with the contract of the snapshot logic pertaining to ‘authentic’ evidentiary image practices today. | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_6.png|thumb|480px|Figure 6: X-post]] | [[File:Marie_Image_6.png|thumb|480px|Figure 6: X-post.]] | ||

The limited media exposure of the press conference stood in contrast to the abundance of other images that circulated in news and social media in the days and weeks following the explosion. Images of despairing women and wounded people hurried off to receive medical help, the chaos of the sites where the dead lay, and analysis of the crater and the missile were frantically shared in a quest for the ‘truth’. These images are pure snapshots of war, dominated by the immediacy and urgency of lifeless bodies shattered on the ground in pools of blood. The composition of the bodies echoes the explosion that forcefully left them motionless on the spot where they have been photographed. The chaos of the scene is palpable, it reverberates from their postures. | The limited media exposure of the press conference stood in contrast to the abundance of other images that circulated in news and social media in the days and weeks following the explosion. Images of despairing women and wounded people hurried off to receive medical help, the chaos of the sites where the dead lay, and analysis of the crater and the missile were frantically shared in a quest for the ‘truth’. These images are pure snapshots of war, dominated by the immediacy and urgency of lifeless bodies shattered on the ground in pools of blood. The composition of the bodies echoes the explosion that forcefully left them motionless on the spot where they have been photographed. The chaos of the scene is palpable, it reverberates from their postures. | ||

With this contrast as an argument, pro-Israeli voices attempted to disregard the press conference video as propaganda or “disaster pornography.” Its staging was said to explicitly counter the fetishizing of evidentiary war images in which, as Thomas Keenan observes, staging equals fake (438). This skepticism caused by judging the validity of the video by its 'form'' (how it visually communicates evidence of the events) creates a distance to its ''content'' (the casualties and horrors of the explosion), a process that somewhat distances its viewers from the horrors it depicts (Sjöholm 166). | With this contrast as an argument, pro-Israeli voices attempted to disregard the press conference video as propaganda or “disaster pornography.” Its staging was said to explicitly counter the fetishizing of evidentiary war images in which, as Thomas Keenan observes, staging equals fake (438). This skepticism caused by judging the validity of the video by its ''form'' (how it visually communicates evidence of the events) creates a distance to its ''content'' (the casualties and horrors of the explosion), a process that somewhat distances its viewers from the horrors it depicts (Sjöholm 166). | ||

Although the video ''was'' staged and choreographed in a rarely seen manner, it fundamentally adheres to the snapshot aesthetics. The video, screenshots, and short clips that circulated on social media, with their poor resolution and unsharp focus testify to the aesthetics pertaining to the hurriedness of the snapshot. In some versions, the dead baby is even obfuscated by pixelation. Furthermore, the fact that it is shot at the actual crime scene of the explosion that happened only hours earlier certainly adds a sense of immediacy and spontaneity; that is, the forensic evidentiary value striven for to trust the images we see. At one point in the long version of the video, a white-gloved hand appears on the left side of the frame, signaling to move a girl’s body into his arms. They clumsily rearrange the small body in front of the livestreaming camera, her head dropping at one point, to be carefully picked up again. This emphasizes that while the scenography is staged, the very event of the press conference seems to be a spontaneous set-up, unpracticed, and put together in a hurry only hours after the tragedy at the very site where it took place. The shock that is still evident in the men’s faces demonstrates the chaos and desperation of the situation, opening for a less dichotomic reading of the video’s rather ambiguous relation between the logic of the snapshot and scenography. | Although the video ''was'' staged and choreographed in a rarely seen manner, it fundamentally adheres to the snapshot aesthetics. The video, screenshots, and short clips that circulated on social media, with their poor resolution and unsharp focus testify to the aesthetics pertaining to the hurriedness of the snapshot. In some versions, the dead baby is even obfuscated by pixelation. Furthermore, the fact that it is shot at the actual crime scene of the explosion that happened only hours earlier certainly adds a sense of immediacy and spontaneity; that is, the forensic evidentiary value striven for to trust the images we see. At one point in the long version of the video, a white-gloved hand appears on the left side of the frame, signaling to move a girl’s body into his arms. They clumsily rearrange the small body in front of the livestreaming camera, her head dropping at one point, to be carefully picked up again. This emphasizes that while the scenography is staged, the very event of the press conference seems to be a spontaneous set-up, unpracticed, and put together in a hurry only hours after the tragedy at the very site where it took place. The shock that is still evident in the men’s faces demonstrates the chaos and desperation of the situation, opening for a less dichotomic reading of the video’s rather ambiguous relation between the logic of the snapshot and scenography. | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_7.png|thumb|480px|Figure: Screenshot of the press conference-video, rearranging positions]] | [[File:Marie_Image_7.png|thumb|480px|Figure: Screenshot of the press conference-video, rearranging positions.]] | ||

A more dialectical understanding of the video as an expansion of snapshot logic helps us understand its potential. The video might on the one hand be understood as ''bearing witness'' to the atrocities happening in Gaza as an image of evidentiary value; at least, this might have been the intention behind the set-up. The shock effect evoked by presenting a ‘staged war’ did manage to hurl the video and screenshots of it into circulation online, to be seen by the world and bear witness to the attack on a civilian hospital. However, it can no longer be found in the archives of the news stations that broadcast it and is now mostly available as very short 1-minute clips on YouTube or X, obfuscated by blurring or pixelation. One might speculate on whether the blunt display of death (e.g., the dead baby with guts spilling out), was perceived as an overexposure of violence. This hyperbolic form in combination with the ‘overly’ choreographed frame of the press conference was perhaps simply too harsh and shocking to have a real effect. | A more dialectical understanding of the video as an expansion of snapshot logic helps us understand its potential. The video might on the one hand be understood as ''bearing witness'' to the atrocities happening in Gaza as an image of evidentiary value; at least, this might have been the intention behind the set-up. The shock effect evoked by presenting a ‘staged war’ did manage to hurl the video and screenshots of it into circulation online, to be seen by the world and bear witness to the attack on a civilian hospital. However, it can no longer be found in the archives of the news stations that broadcast it and is now mostly available as very short 1-minute clips on YouTube or X, obfuscated by blurring or pixelation. One might speculate on whether the blunt display of death (e.g., the dead baby with guts spilling out), was perceived as an overexposure of violence. This hyperbolic form in combination with the ‘overly’ choreographed frame of the press conference was perhaps simply too harsh and shocking to have a real effect. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

Returning to Rosler’s photomontages, we can see that the press conference video conceptually mimics the ''deframing'' and ''reframing'' of elements identified above. By cutting out photos of wounded bodies and pasting them onto a backdrop of American living rooms, Rosler sought to deframe the perception of the war in Vietnam. By uniting contradictory logical frames, the press conference video challenges the snapshot's axiom by expanding its boundaries and creating a space for expressing the desperation of the oppressed civil population in Gaza. In a Rosler-like manner, the video ''de-frames'' the images of the dead by removing them from the spot where they died and ''re-framing'' them into the curated performance of the press conference. Like the other elements—spotlights, stage, microphones—the dead bodies have been staged within the camera’s frame to make a statement of facts. As already argued, the staging takes place under obviously desperate circumstances, in which this aestheticization becomes a way to express the condition of despair. Corresponding to Georges Didi-Huberman’s description of “agonizing bodies,” the speakers at the press conference gesticulate a resistance that becomes evident when the frame expands and alters the perception: suddenly the speakers’ constrained grimaces do not correspond to the shock of seeing this surreal scenography. The expected scream that evades their mouths is replaced by clenched teeth (see images 8 and 9), a sense of despair pressing from within: “Fury makes men grind their teeth” (Didi-Huberman 14). | Returning to Rosler’s photomontages, we can see that the press conference video conceptually mimics the ''deframing'' and ''reframing'' of elements identified above. By cutting out photos of wounded bodies and pasting them onto a backdrop of American living rooms, Rosler sought to deframe the perception of the war in Vietnam. By uniting contradictory logical frames, the press conference video challenges the snapshot's axiom by expanding its boundaries and creating a space for expressing the desperation of the oppressed civil population in Gaza. In a Rosler-like manner, the video ''de-frames'' the images of the dead by removing them from the spot where they died and ''re-framing'' them into the curated performance of the press conference. Like the other elements—spotlights, stage, microphones—the dead bodies have been staged within the camera’s frame to make a statement of facts. As already argued, the staging takes place under obviously desperate circumstances, in which this aestheticization becomes a way to express the condition of despair. Corresponding to Georges Didi-Huberman’s description of “agonizing bodies,” the speakers at the press conference gesticulate a resistance that becomes evident when the frame expands and alters the perception: suddenly the speakers’ constrained grimaces do not correspond to the shock of seeing this surreal scenography. The expected scream that evades their mouths is replaced by clenched teeth (see images 8 and 9), a sense of despair pressing from within: “Fury makes men grind their teeth” (Didi-Huberman 14). | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_8.png|thumb|480px|Figure 8: Details of facial expressions]] | [[File:Marie_Image_8.png|thumb|480px|Figure 8: Details of facial expressions.]] | ||

[[File:Marie_Image_9.png|thumb|480px|Figure 9: Details of facial expressions]] | [[File:Marie_Image_9.png|thumb|480px|Figure 9: Details of facial expressions.]] | ||

Viewed in a historical context, as an instance of the Palestinian resistance practice ''sumud'', the meshing of logics and frames in the video appears less deliberately ‘staged’ and more as a spontaneous form of everyday resistance under extremely desperate circumstances. In Arabic, the word ''sumud'' means “steadfast perseverance” and as a term, it broadly covers a collective Palestinian nonviolent everyday resistance against Israel’s occupation (Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question). The exceptional conditions of violence and mainstream media obfuscation and restrictions, that have been observed since Oct 7th, 2023, stand out from the previous Israeli attacks on Gaza. Due to this, the everyday acts of resistance have new conditions, partially because the everyday is now a warzone, but also due to the restricted media coverage, that forces the victims to ‘broadcast their own destruction’ (The Editors). The doctors leading the press conference in their scrubs (perhaps the same ones they wore when the attack took place?) next to the crater outside the hospital building manifest the merging of warzone and everyday life. The video’s meshing of logics makes it possible to express the clash between the warzone and everyday life that the Palestinian population experiences. In this light, the scenographic arrangement of dead bodies could be interpreted as an act of everyday resistance taking place under desperate circumstances. | Viewed in a historical context, as an instance of the Palestinian resistance practice ''sumud'', the meshing of logics and frames in the video appears less deliberately ‘staged’ and more as a spontaneous form of everyday resistance under extremely desperate circumstances. In Arabic, the word ''sumud'' means “steadfast perseverance” and as a term, it broadly covers a collective Palestinian nonviolent everyday resistance against Israel’s occupation (Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question). The exceptional conditions of violence and mainstream media obfuscation and restrictions, that have been observed since Oct 7th, 2023, stand out from the previous Israeli attacks on Gaza. Due to this, the everyday acts of resistance have new conditions, partially because the everyday is now a warzone, but also due to the restricted media coverage, that forces the victims to ‘broadcast their own destruction’ (The Editors). The doctors leading the press conference in their scrubs (perhaps the same ones they wore when the attack took place?) next to the crater outside the hospital building manifest the merging of warzone and everyday life. The video’s meshing of logics makes it possible to express the clash between the warzone and everyday life that the Palestinian population experiences. In this light, the scenographic arrangement of dead bodies could be interpreted as an act of everyday resistance taking place under desperate circumstances. | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

''Sumud'' has been defined by a practice of ‘remaining’ or ‘enduring’ Israel’s occupation. By broadcasting an act of remaining in the rubbles – staying and enduring – as a form of ''sumud'', the press conference connotes the historical emphasis on “remaining on Palestinian land or in the refugee camps despite hardship” (IEOTPQ). In this sense, the press conference ''as an act'' manifests the adapted gospel song “We shall not be moved”, originally used in the civil rights movement and recently chanted by student protesters against the genocide in Gaza all over the world. In this reading, the video can thus simultaneously be seen as a counterimage and an after- image: by striking back ''with'' and ''through'' after-images of ‘truth,’ it challenges the conventional approach to depicting images of war. The video shows the aftermath of the explosion after the screams for the lost children have died out, bodies gathered as evidence for the world to see the atrocities of Israel’s war in Gaza. Through this scenography of resistance, the video breaks with the established aestheticization of war and expands the axiomatic logic of today’s war images. The scenography of the video thus serves a similar purpose to that of Rosler’s: re-framing the narrative of the conflict by showing what Jacques Rancière (concerning Rosler’s photomontages) described as “the obvious reality that you do not want to see” (28). By displaying the casualties of the explosion, the video bears witness to the suffering and horrors of Israel’s war in Gaza. The staging thus becomes an evidentiary practice, inter-visually connected to historical practices of documenting the horrors of war, e.g. evident in the aftermath of WW2. In this way, the video contests the fetishizing of evidentiary images today, by revolting against the idea that images of war should be pixelated or spontaneous to support their credibility or authenticity. From the perspective of the repressed, this video can thus be read as resistance, or in Didi-Huberman’s words, “a gesture of despair before the atrocity that is unfolding below, a gesture calling for help in the direction of the eventual saviors outside of the frame and, above all, a gesture of tragic imprecation beyond—or through—every appeal to vengeance” (10–11). | ''Sumud'' has been defined by a practice of ‘remaining’ or ‘enduring’ Israel’s occupation. By broadcasting an act of remaining in the rubbles – staying and enduring – as a form of ''sumud'', the press conference connotes the historical emphasis on “remaining on Palestinian land or in the refugee camps despite hardship” (IEOTPQ). In this sense, the press conference ''as an act'' manifests the adapted gospel song “We shall not be moved”, originally used in the civil rights movement and recently chanted by student protesters against the genocide in Gaza all over the world. In this reading, the video can thus simultaneously be seen as a counterimage and an after- image: by striking back ''with'' and ''through'' after-images of ‘truth,’ it challenges the conventional approach to depicting images of war. The video shows the aftermath of the explosion after the screams for the lost children have died out, bodies gathered as evidence for the world to see the atrocities of Israel’s war in Gaza. Through this scenography of resistance, the video breaks with the established aestheticization of war and expands the axiomatic logic of today’s war images. The scenography of the video thus serves a similar purpose to that of Rosler’s: re-framing the narrative of the conflict by showing what Jacques Rancière (concerning Rosler’s photomontages) described as “the obvious reality that you do not want to see” (28). By displaying the casualties of the explosion, the video bears witness to the suffering and horrors of Israel’s war in Gaza. The staging thus becomes an evidentiary practice, inter-visually connected to historical practices of documenting the horrors of war, e.g. evident in the aftermath of WW2. In this way, the video contests the fetishizing of evidentiary images today, by revolting against the idea that images of war should be pixelated or spontaneous to support their credibility or authenticity. From the perspective of the repressed, this video can thus be read as resistance, or in Didi-Huberman’s words, “a gesture of despair before the atrocity that is unfolding below, a gesture calling for help in the direction of the eventual saviors outside of the frame and, above all, a gesture of tragic imprecation beyond—or through—every appeal to vengeance” (10–11). | ||

The press conference video was staged, meant to be seen. The bodies lying still in the frame do not reverberate the immediacy of the explosion, but rather the desperate conditions of war that disrupt the everyday life of the Palestinian citizens. By not instantly disregarding the staging as propaganda or disaster pornography, within a consensus of the mediatization of war images that hinges on a dichotomy between the evidentiary and staging, but rather viewing it as an expansion of the snapshot logic, it becomes possible to interpret the video as an act of everyday resistance. The men sitting in the front are not in official clothes or scrubs and their primary role is to literally ''bear'' witness to the violence by physically holding the lifeless bodies of (their own?) children. Taking Donna | The press conference video was staged, meant to be seen. The bodies lying still in the frame do not reverberate the immediacy of the explosion, but rather the desperate conditions of war that disrupt the everyday life of the Palestinian citizens. By not instantly disregarding the staging as propaganda or disaster pornography, within a consensus of the mediatization of war images that hinges on a dichotomy between the evidentiary and staging, but rather viewing it as an expansion of the snapshot logic, it becomes possible to interpret the video as an act of everyday resistance. The men sitting in the front are not in official clothes or scrubs and their primary role is to literally ''bear'' witness to the violence by physically holding the lifeless bodies of (their own?) children. Taking Donna Haraway’s “staying with the trouble” phrase to its extreme, the civilians in this video are ‘staying in the rubbles’ to bear witness in front of the world and express the conditions of despair and desperation in Gaza. | ||

== Works cited == | == Works cited == | ||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. ''Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth.'' Verso Books, 2021. | Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. ''Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth.'' Verso Books, 2021. | ||

Ganguly, Manisha, Emma Graham-Harrison, Jason Burke, Elena Morresi, Ashley Kirk, and Lucy Swan. “Al-Ahli Arab Hospital: Piecing Together What Happened as Israel Insists Militant Rocket to Blame.” ''The Guardian,'' October 18, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/18/al-ahli-arab-hospital-piecing-together-what- happened-as-israel-insists-militant-rocket-to-blame. | Ganguly, Manisha, Emma Graham-Harrison, Jason Burke, Elena Morresi, Ashley Kirk, and Lucy Swan. “Al-Ahli Arab Hospital: Piecing Together What Happened as Israel Insists Militant Rocket to Blame.” ''The Guardian,'' October 18, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/18/al-ahli-arab-hospital-piecing-together-what-happened-as-israel-insists-militant-rocket-to-blame. | ||

Hirschhorn, Thomas. ''Pixel-Collage.'' 2015, http://www.thomashirschhorn.com/pixel-collage/, 2024. | Hirschhorn, Thomas. ''Pixel-Collage.'' 2015, http://www.thomashirschhorn.com/pixel-collage/, 2024. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

== Biography == | == Biography == | ||

Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias is a Ph.D. Candidate at Aarhus University, School of Communication and Culture affiliated with the department for Art history, Aesthetics and Culture and Museology. Her research centers around war and digital images, the militarization of the everyday life as well as contemporary art and other aesthetic image practices. | Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias is a Ph.D. Candidate at Aarhus University, School of Communication and Culture affiliated with the department for Art history, Aesthetics and Culture and Museology. Her research centers around war and digital images, the militarization of the everyday life as well as contemporary art and other aesthetic image practices. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0217-1167 | ||

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0217-1167 | |||

[[Category: Content Form]] | [[Category: Content Form]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:41, 13 November 2024

Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias

Logics of War

Logics of War

Abstract

As manifested in Jean Baudrillard’s notoriously provoking claim that “the Gulf War did not take place,” mediatization of war has long been associated with illusion. Today, war images that circulate online are increasingly judged by their proximity to ‘truth,’ eliciting a skepticism towards their ‘evidentiary’ value. By juxtaposing Baudrillard’s reading of the mediatization of the Gulf War with the contemporary image theories of e.g. Cecilia Sjöholm and Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, the article explores how this skepticism is expressed in a contemporary context. Through visual analysis of a YouTube video of a press conference held at the bombed Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza, it examines the relationship between the form through which the war is perceived (the images) and their content (the ‘realities’ of war). Through a lens offered by Georges Didi-Huberman, the article concludes by suggesting that by expanding what I term the snapshot logic of war images to embrace a scenography of war, the press conference video gives form to the condition of desperation and suffering in Gaza.

Introduction

There is a video—or rather a pixelated, slightly blurry excerpt—circulating on social media. The video was originally a live-streamed press conference held by the Ministry of Health in Gaza in response to the airstrike that hit Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital on October 17, 2023, leaving hundreds dead and many more trapped under the rubble. The video and the screenshots that quickly circulated show members of the hospital’s medical staff gathered around a podium amidst the white-sheet-covered corpses of the explosion’s victims. Three to four men squat in front of the podium, holding the bodies of an uncovered baby and a partially covered young girl. Judging by the constrained distress on the men’s faces, they seem in disbelief over what they are holding. The shock of the situation is palpable, the men alternating between stiffly looking away and bowing their heads to face the dead children in their arms and on the ground before them.

Although the video was broadcast on several news channels, including the Arabic Al Jazeera, the uncut version is no longer available—neither in their archive nor on YouTube. However, screenshots and ultrashort excerpts of the video quickly circulated on platforms such as X, Instagram, and YouTube. In this way, it partakes in the “swarm circulation” that makes up today’s online information stream, which favors clips and screenshots over full-length videos, “previews rather than screenings” as the artist and critic Hito Steyerl formulates it (“In Defence” 7). At the time of writing this article, the video evidently exists solely as what Steyerl calls a “copy in motion”; as social media content, symptomatic of the ephemerality of the large amounts of images that circulate online today. The excerpt this paper refers to is a 17:21-minute-long version, posted on YouTube on October 18, 2023, the longest version that seems to still exist online (CasaInfo).

The video quickly became the focal point of a subsequent narrative battle playing out online. While Palestinian officials reported that the destruction of the hospital was a result of the ongoing Israeli airstrikes in Gaza, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) denied culpability, instead blaming a failed rocket launch by the Palestinian group Islamic Jihad. The battle to prove these contradictory narratives catalyzed an intense image war conducted online—with varying credibility—through forensic image analysis. My investigative focal point, however, is the press conference video through which I analyze the contemporary conditions for perceiving war via images. My focus lies in analyzing the logics pertaining to the video’s reception, not on forensic dissection of its “evidentiary value” and factuality (Fuller and Weizman), like that offered by Forensic Architecture, for example.

In this article, I will show that the video exposes a conflict in the perception of circulating images, raising the question of whether, and how, war imagery can be perceived as both staged and evidentiary at the same time? The article investigates the mediatization of war through circulating images by scrutinizing how the form through which distant wars are perceived (the images) impacts the reception of their content (the ‘realities’ of war). I do this by juxtaposing Jean Baudrillard’s manifestation of skepticism as an inherent part of the mediatization of the Gulf War, with contemporary image theories, such as Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman’s idea of images as “evidentiary” and Cecilie Sjöholm’s “forensic turn of images.” I identify two logics of perception— that I term the ‘snapshot of war’ (pertaining to evidentiary value) and the ‘scenography of war’ (often associated with manipulation) —and use these as the analytical framework for my reading of the video. The article concludes by urging against dismissing the scenographic elements as mere manipulation or fabrication. Instead, moving beyond the dichotomies between ‘fake’ and ‘true’, I suggest how the video expands the snapshot logic thus creating a powerful medium to convey the conditions of despair and desperation in Gaza.

“This is Not a War”: War and Illusion

As epitomized in Baudrillard’s notorious, provoking claim that “the Gulf War did not take place,”( 1991) the mediatization of warfare has long created a certain sense of skepticism, provoking an impression of war itself as an overexposed, representative, and even ‘unreal’ or ‘illusive’ event. In his sequence of essays in Libération, Baudrillard obviously did not argue that the atrocities in the Gulf did not actually happen; rather, he claimed that the events in the Gulf were 1) not a war per se and 2) thoroughly curated. Exceeding a death toll of one hundred thousand Iraqis, the Allied forces’ display of aerial power was so overwhelming that it transcended the conventional notion of war as a “dual relation between two adversaries” (Baudrillard 62). Instead, as Baudrillard succinctly put it, it was an “electrocution” of a defenseless enemy (62), or in Grégoire Chamayou’s much later but blatant phrasing regarding “unilateral warfare,” it was “quite simply, slaughter” (13).

With his second point, that the war was a curated event, Baudrillard argued that the production and distribution of images released to the public were strictly governed. Because the civilian population in the West did not see the atrocities happening in the Gulf, for them it “did not take place” at all (equivalent to the contemporary logic: Facebook or it didn’t happen). What the civil population in the West saw was a ‘facelifted’ war seldomly showing images of human casualties, “none from the Allied forces” (Baudrillard 6), or, as Paul Patton wrote in his introduction to the 1995 edition of Baudrillard’s text, a new level of military censorship over the production and circulation of images projected a “clean” war, manipulating the West’s perception of events (Baudrillard 3).

Applying Baudrillard to the current conflict in Gaza, Geoff Shullenberger observes the shift that Baudrillard reacted to, namely that “war had once been an event that occurred in the world; only later, often much later, were its facts conveyed by journalists, diarists, poets, and novelists.” In his reading of the situation in Gaza, Shullenberger notes how the new media landscape has sparked a radical change in the ontology of warfare, extending beyond Baudrillard’s 30-year-old observation. Synthesizing the Baudrillard and Shullenberger arguments, it can be said, that the broadcast media allowed for a shift; that is, from warfare as an event that literally “took up place” in the world—the mediatization happening in hindsight—to conditions of immediate capture and dissemination of war causing the ‘representation of’ and the ‘war itself’ to become indistinguishable. Patton tellingly describes the perception of the Gulf War as a “perfect Baudrillardian simulacrum, a hyperreal scenario in which events lose their identity and signifiers fade into one another” (Patton in Baudrillard 2).

The indistinguishability between the war itself and the mediatization of it, perhaps better understood as content and form, is increasingly pertinent in the conduct of today’s hyper- mediatized warfare. The heritage of skepticism that Baudrillard’s essays manifested is still inherent in the contemporary perception of war today. However, while Baudrillard described how the Gulf War was narrated through an “absence of images and profusion of commentary” (29), current wars can be said to be conducted through an abundance of both. As wars are increasingly carried out with and through images, new questions about conflicts of reception and “evidentiary value” arise.

For instance, in Baudrillard’s description of the Gulf War, the superior Allied Forces restricted the perception through a curated distribution of information and imagery. Moving beyond Baudrillard to subsequent works like Fuller and Weizman’s Investigative Aesthetics one can discern how the contemporary media portrayal of warfare presents itself differently today, especially considering their term “hyperaesthesia.” Characterized by an overload of the senses, hyperaesthesia is a technique to drown (unwanted) images “within a flood of other images and information.” As a technique, it thus aims at “seeding doubt by generating more information than can be processed” (Fuller and Weizman 85).

A paradigmatic instance of hyperaesthesia is the aftermath of the explosion at Al-Ahli Baptist Hospital in Gaza when the internet instantly flooded with partisan reports, counternarratives, investigative articles, and X-posts comparing various ‘forensic’ image and video analyses. Palestinian officials immediately blamed Israel for what they called a “horrific massacre”; a statement subsequently contested by the IDF. As noted above, the battle to prove these contradictory narratives catalyzed an intense image war conducted through forensic image analysis online. Although the Israeli narrative around the explosion was largely contested, not only on social media but also by more well-credited agencies like Forensic Architecture and other preliminary investigative analyses, the hyperaesthesia of information muddied the perception of what was ‘real’ and ‘fake,’ making it impossible to distinguish propaganda from fact.

As an example of this one could argue that, on the one hand, the Israeli government actively restricts media coverage of their war in Gaza in the manner that Baudrillard described for the Gulf War. For instance, most recently, Israel issued a ban on Al Jazeera and is, as the writing collective The Editors state, “targeting and killing photojournalists; because Israel has denied foreign journalists access to Gaza, with the exception of a few IDF-guided tours.” On the other hand, while this is impactful, today, imagery of the effects of war is not only available but unavoidable. As is demonstrated in The Editors’ article Who Sees Gaza? A Genocide in Images, the mediatization of the war has evolved into a collective process of “sense-making,” in Fuller and Weizman’s terms, as the production and dissemination of images no longer accrue to the news media, but increasingly to the victims themselves: “the people of Gaza showed the world what the mainstream media could not: wounded civilians, leveled buildings, long lines of dead bodies wrapped in white sheets, bombed-out universities, bombed-out mosques, toddlers trembling in shock and covered in the grey, ashy dust of debris” (The Editors). Regardless of Israel’s restriction of media and press, the war takes place virtually before our eyes. In the words of lawyer Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, when presenting South Africa’s case against Israel at the International Court of Justice, it is “the first genocide in history where its victims are broadcasting their own destruction in real-time in the desperate, so far vain, hope that the world might do something” (The Editors).

Gaza is thus an instance of overexposure to war today. In Baudrillard’s reading of the mediatization of the Gulf War, the focus was largely on what was not shown, not seen in a quest to maintain a certain level of support for the war. Today, the illusion linked to not seeing the horrors of the Gulf War has been replaced by a disillusionment caused by seeing too much, eliciting a new type of skepticism towards the evidentiary value of images. While the political task then involved what could be called de-aestheticization by not showing, the political task in warfare today is fundamentally a question of aestheticizing, in the sense proposed by Fuller and Weizman; that is, making visible or “attuned to sensing” (33).

Baudrillard’s rendering of the mediatization of war as inherently illusional corresponds to the largely accepted logic that aestheticizations of war are contradictory to evidentiary image practices. By methods of “investigative aesthetics,” Fuller and Weizman challenge this axiom: “The terms ‘aesthetics’ and ‘to aestheticise’ [...] seem to be anathema to familiar investigative paradigms because they signal manipulation, emotional or illusionistic trickery, the expression of feelings and the arts of rhetoric rather than the careful protocols of truth” (15). The mediatization, or in Fuller and Weizman’s terms the aestheticization, of war has become an arena for investigation: war images are constantly subjected to skepticism, fact-checking, and image analysis in a debate over their evidentiary value. The conflict today does not so much pertain to the problematics of aestheticizing images of war, but rather to the fetishizing their potential evidentiary value. By being aestheticized—made sensible to the world—images of war are systematically made subject to ‘evidentizing’ and (dis)regarded by their proximity to ‘truth.’

Consequently, hyperaesthesia divides the perception of war between 1) a skepticism towards the ‘evidentiary value’ of the images we see and 2) what has been termed anaesthetics, a mental state caused by overexposure to violent imagery of war. The anaesthetic response to the endless stream of violent imagery is characterized by numbness and resignation toward making sense at all, a sort of “blockage to make sense” (Fuller and Weizman 85). Susan Buck-Morss describes this feeling of numbness in her essay on Walter Benjamin, linking anesthetization to overstimulation: “Bombarded with fragmentary impressions they see too much – and register nothing. Thus the simultaneity of overstimulation and numbness is characteristic of the new synaesthetic organization as anaesthetics” (Buck-Morss 18).

Fuller and Weizman’s use of images as evidence is symptomatic of the change in the ontology of warfare today often described as outright image wars. Professor in aesthetics Cecilia Sjöholm registers this shift as the “forensic turn of images,” whereby an image’s function has changed from primarily “ethical” to a “statement of facts,” and it “is no longer a document of conscience, but a judicial one” (Sjöholm 166). This turn manifested itself in an article from The Guardian titled Al-Ahli Arab Hospital: Piecing Together What Happened as Israel Insists Militant Rocket to Blame (Ganguly et. al). Here, images were featured alongside video analysis of the strike as a kind of public and open exhibition of evidentiary images. According to Sjöholm, the reception of images today is less centered on the emotional responses they evoke than on their forensic and evidentiary value, which she slightly counter- intuitively dubs “aesthetic”: “Today the question is not what we feel when we see an image – the question is aesthetic: what can we say about its statement of fact, its perspective” (Sjöholm 167, my emphasis). The spontaneous emotional response is instantly accompanied or even surpassed by skepticism towards its statement of facts or evidentiary value. Just as the over-stimuli of hyperaesthesia causes numbness or resignation toward violent images of war (an undermining of the initial emotional response), the skepticism regarding the evidentiary value of the image that Sjöholm talks about could be said to create a “cold” analytical distance that abstracts from the horrors of the content of the images toward the formal properties of evidence.

Logics of Perception: Staging a Catastrophe

The composition of the press conference video was meant to be seen, it was staged, or it became staged and thus opposed and affirmed in one and the same gesture the pursuit of authentic images of war—challenging our distrust toward them. In unfolding this statement further, the following section analyzes the press conference video to investigate how we can read and understand manifestations of skepticism toward representations of war imagery today. I will view the video as an attempt to show the ‘desperation of war’ by expanding beyond a traditional snapshot of war logic to embrace a new ‘stagedness’ characteristic of what I call the scenography of war.

To first clarify the concept of snapshots of war, these are the very images that The Editors refer to in their abovementioned article. They are not taken by photojournalists but by people living amid disaster, chaos, and unstable internet connectivity. As these images are, for the most part, taken by camera phones, comprised to be uploaded via a poor connection, their aesthetics reflect a hasty capture amid the disorder of conflict: a sort of snapshot aesthetics. We can develop this further by drawing on the artist Thomas Hirschhorn, who, speaking about his Pixel-Collage series (2015), observed that “Pixelating – or blurring has taken over the role of authenticity.” In this view, blurriness and pixelation have become technical testimonies of ‘truth’ or evidentiary value in images of war. Similarly, we have become accustomed to perceiving the war through what Steyerl terms “poor images”; that is, low-resolution images, that circulate online, are swiftly shared via social and news media and often partially obfuscated by pixelation or blurring. They are “pictures that appear more immediate, which offer increasingly less to see” (Steyerl 7). Such alleged immediate and spontaneous representations produce an experience of ‘authenticity’ that seems to add a certain evidentiary value, as they almost render a seamless mediatization. This is the reasoning behind what I term the snapshot of war; a logic of perception in which immediacy and spontaneity signify authenticity and evidentiary value.

The second key concept here is that which I call the scenography of war, in which a sense of performativity or staging dominates the spatial arrangement of elements. Drawing on these two concepts, I argue that the disturbing thing about the video under discussion is not so much its extreme gruesomeness, epitomized by the dead baby in the arms of the man sitting at the center of the frame, blood covering its small body in place of a sheet. Rather, it is the clash between the two seemingly contradictory logics pertaining to images of war; the snapshot and the scenography of war. As I will explain, by drawing on the montages of artist Martha Rosler, the clash between these two seemingly contradictory logical frames creates a shock effect. In her photomontage series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–1972), Rosler combined photographs of wounded bodies from the Vietnam War with magazine cut-outs of flawless American living rooms. In rearranging the composition of elements, Rosler changed the frame of reference to perceiving the war, suggesting a skepticism toward its mediatization. The clash between two conflicting frames in her photomontages, the warzone, and everyday life, elicits a shock effect.

In the Gaza video, however, the consolidation of the press conference frame and the warzone frame is not in itself shocking; rather, it is the way the latter has been choreographed, that stands out. While Rosler’s collages consisted of actual photographic elements, they were experienced through their context as artworks—overtly staged and manipulated as part of their methodology. In contrast, the video of the press conference in Gaza is not a post-processed artistic expression of the war, but a broadcast relayed live from the battlefield. While Rosler’s artworks make no evidentiary claim, the images in the video are first and foremost judged by what Sjöholm terms their “statements of fact.”

In one of the versions of the press conference video available online, the frame is initially zoomed in on the speakers at the podium, their faces serious as per the implicit protocol of a press conference of this gravity. The aesthetic logic here is similar to Rosler’s artworks: unremarkably staged. The spatial arrangement of the elements follows a pre-set scenography of expected components like bright lights, a stage with microphones, and men in authority-evoking clothes, hands crossed in front and constrained facial expressions. While this predefined ‘stagedness’ does not evoke any skepticism towards the factuality of the video, the zoom-out adds a second frame; that of a ‘staged’ warzone, revealing a ‘mass grave’ of dead bodies arranged around the podium, covered by white, blood-stained sheets (see Figure 1). This is where the perception of the video shifts and the mediatization of the war is highlighted by the aestheticized character of the crime scene, which can best be described as a scenography of war: staged to be seen in a certain way. The use of aesthetic strategies in this composition staged for the camera, meant to be seen, connotes a mediatization that exceeds merely representing the war. The staging of the bodies is unexpected, and the lack of spontaneity in their positioning in front of the camera breaks with the snapshot logic, stretching its boundaries.

The unexpected frame of the re-arranged warzone somehow makes the viewer conscious of the mediatization of the events it depicts, as they are overtly ‘performed’ for the camera, an aesthetics notoriously linked with manipulation or propaganda. This evokes an initial suspicion towards the credibility of the video, raising Steyerl’s skepticism in Documentary Uncertainty, “Is this really true?”. The very thought of practically preparing and arranging the podium and the bodies is absurd: Did the speakers straddle the dead bodies to reach the stage? Did someone yell “action” before livestreaming this macabre scene? One X-user captured the feeling of cautious skepticism that this clash of logics evokes, with the phrase “The most surreal zoom I’ve ever seen,” pinpointing how the staging of the warzone in a horrifying choreography of war breaks with the contract of the snapshot logic pertaining to ‘authentic’ evidentiary image practices today.

The limited media exposure of the press conference stood in contrast to the abundance of other images that circulated in news and social media in the days and weeks following the explosion. Images of despairing women and wounded people hurried off to receive medical help, the chaos of the sites where the dead lay, and analysis of the crater and the missile were frantically shared in a quest for the ‘truth’. These images are pure snapshots of war, dominated by the immediacy and urgency of lifeless bodies shattered on the ground in pools of blood. The composition of the bodies echoes the explosion that forcefully left them motionless on the spot where they have been photographed. The chaos of the scene is palpable, it reverberates from their postures.

With this contrast as an argument, pro-Israeli voices attempted to disregard the press conference video as propaganda or “disaster pornography.” Its staging was said to explicitly counter the fetishizing of evidentiary war images in which, as Thomas Keenan observes, staging equals fake (438). This skepticism caused by judging the validity of the video by its form (how it visually communicates evidence of the events) creates a distance to its content (the casualties and horrors of the explosion), a process that somewhat distances its viewers from the horrors it depicts (Sjöholm 166).

Although the video was staged and choreographed in a rarely seen manner, it fundamentally adheres to the snapshot aesthetics. The video, screenshots, and short clips that circulated on social media, with their poor resolution and unsharp focus testify to the aesthetics pertaining to the hurriedness of the snapshot. In some versions, the dead baby is even obfuscated by pixelation. Furthermore, the fact that it is shot at the actual crime scene of the explosion that happened only hours earlier certainly adds a sense of immediacy and spontaneity; that is, the forensic evidentiary value striven for to trust the images we see. At one point in the long version of the video, a white-gloved hand appears on the left side of the frame, signaling to move a girl’s body into his arms. They clumsily rearrange the small body in front of the livestreaming camera, her head dropping at one point, to be carefully picked up again. This emphasizes that while the scenography is staged, the very event of the press conference seems to be a spontaneous set-up, unpracticed, and put together in a hurry only hours after the tragedy at the very site where it took place. The shock that is still evident in the men’s faces demonstrates the chaos and desperation of the situation, opening for a less dichotomic reading of the video’s rather ambiguous relation between the logic of the snapshot and scenography.

A more dialectical understanding of the video as an expansion of snapshot logic helps us understand its potential. The video might on the one hand be understood as bearing witness to the atrocities happening in Gaza as an image of evidentiary value; at least, this might have been the intention behind the set-up. The shock effect evoked by presenting a ‘staged war’ did manage to hurl the video and screenshots of it into circulation online, to be seen by the world and bear witness to the attack on a civilian hospital. However, it can no longer be found in the archives of the news stations that broadcast it and is now mostly available as very short 1-minute clips on YouTube or X, obfuscated by blurring or pixelation. One might speculate on whether the blunt display of death (e.g., the dead baby with guts spilling out), was perceived as an overexposure of violence. This hyperbolic form in combination with the ‘overly’ choreographed frame of the press conference was perhaps simply too harsh and shocking to have a real effect. Currently, the video’s status is pending between being rejected as ‘propaganda’ and taking part in the overstimulation of hyperaesthesia, its sentiment getting partially lost in the abundance of images online, generating an anaesthetics toward the violence. In contrast to the extreme exposure of images of the crater, the absence of the video in the media landscape in the subsequent days and weeks testifies to this. Despite this ongoing uncertainty, we can say that the video provides a different kind of testimony to the desperation of the condition, one of penetrating desperation, giving form to a practice of resistance.

A Scenography of Resistance

Finally, I will read the video in light of Thomas Keenan, who abandons the dichotomous relationship between snapshot and scenography just discussed and suggests a different reception of images. Specifically, Keenan observes that “there are things which happen in front of cameras that are not simply true or false, not simply representations and references, but rather opportunities, events, performances, things that are done and done for the camera, which come into being in a space beyond truth and falsity that is created in view of mediation and transmission” (1). Following Keenan’s train of thought, I explore what might happen if we read the clash between frames and logics in the press conference video as a form through which the video can be (perceived as) both staged and evidentiary at the same time, suggesting a reading in which the element of scenography expands the snapshot logic and creates a space for sensing the war differently.

Returning to Rosler’s photomontages, we can see that the press conference video conceptually mimics the deframing and reframing of elements identified above. By cutting out photos of wounded bodies and pasting them onto a backdrop of American living rooms, Rosler sought to deframe the perception of the war in Vietnam. By uniting contradictory logical frames, the press conference video challenges the snapshot's axiom by expanding its boundaries and creating a space for expressing the desperation of the oppressed civil population in Gaza. In a Rosler-like manner, the video de-frames the images of the dead by removing them from the spot where they died and re-framing them into the curated performance of the press conference. Like the other elements—spotlights, stage, microphones—the dead bodies have been staged within the camera’s frame to make a statement of facts. As already argued, the staging takes place under obviously desperate circumstances, in which this aestheticization becomes a way to express the condition of despair. Corresponding to Georges Didi-Huberman’s description of “agonizing bodies,” the speakers at the press conference gesticulate a resistance that becomes evident when the frame expands and alters the perception: suddenly the speakers’ constrained grimaces do not correspond to the shock of seeing this surreal scenography. The expected scream that evades their mouths is replaced by clenched teeth (see images 8 and 9), a sense of despair pressing from within: “Fury makes men grind their teeth” (Didi-Huberman 14).

Viewed in a historical context, as an instance of the Palestinian resistance practice sumud, the meshing of logics and frames in the video appears less deliberately ‘staged’ and more as a spontaneous form of everyday resistance under extremely desperate circumstances. In Arabic, the word sumud means “steadfast perseverance” and as a term, it broadly covers a collective Palestinian nonviolent everyday resistance against Israel’s occupation (Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question). The exceptional conditions of violence and mainstream media obfuscation and restrictions, that have been observed since Oct 7th, 2023, stand out from the previous Israeli attacks on Gaza. Due to this, the everyday acts of resistance have new conditions, partially because the everyday is now a warzone, but also due to the restricted media coverage, that forces the victims to ‘broadcast their own destruction’ (The Editors). The doctors leading the press conference in their scrubs (perhaps the same ones they wore when the attack took place?) next to the crater outside the hospital building manifest the merging of warzone and everyday life. The video’s meshing of logics makes it possible to express the clash between the warzone and everyday life that the Palestinian population experiences. In this light, the scenographic arrangement of dead bodies could be interpreted as an act of everyday resistance taking place under desperate circumstances.

Sumud has been defined by a practice of ‘remaining’ or ‘enduring’ Israel’s occupation. By broadcasting an act of remaining in the rubbles – staying and enduring – as a form of sumud, the press conference connotes the historical emphasis on “remaining on Palestinian land or in the refugee camps despite hardship” (IEOTPQ). In this sense, the press conference as an act manifests the adapted gospel song “We shall not be moved”, originally used in the civil rights movement and recently chanted by student protesters against the genocide in Gaza all over the world. In this reading, the video can thus simultaneously be seen as a counterimage and an after- image: by striking back with and through after-images of ‘truth,’ it challenges the conventional approach to depicting images of war. The video shows the aftermath of the explosion after the screams for the lost children have died out, bodies gathered as evidence for the world to see the atrocities of Israel’s war in Gaza. Through this scenography of resistance, the video breaks with the established aestheticization of war and expands the axiomatic logic of today’s war images. The scenography of the video thus serves a similar purpose to that of Rosler’s: re-framing the narrative of the conflict by showing what Jacques Rancière (concerning Rosler’s photomontages) described as “the obvious reality that you do not want to see” (28). By displaying the casualties of the explosion, the video bears witness to the suffering and horrors of Israel’s war in Gaza. The staging thus becomes an evidentiary practice, inter-visually connected to historical practices of documenting the horrors of war, e.g. evident in the aftermath of WW2. In this way, the video contests the fetishizing of evidentiary images today, by revolting against the idea that images of war should be pixelated or spontaneous to support their credibility or authenticity. From the perspective of the repressed, this video can thus be read as resistance, or in Didi-Huberman’s words, “a gesture of despair before the atrocity that is unfolding below, a gesture calling for help in the direction of the eventual saviors outside of the frame and, above all, a gesture of tragic imprecation beyond—or through—every appeal to vengeance” (10–11).

The press conference video was staged, meant to be seen. The bodies lying still in the frame do not reverberate the immediacy of the explosion, but rather the desperate conditions of war that disrupt the everyday life of the Palestinian citizens. By not instantly disregarding the staging as propaganda or disaster pornography, within a consensus of the mediatization of war images that hinges on a dichotomy between the evidentiary and staging, but rather viewing it as an expansion of the snapshot logic, it becomes possible to interpret the video as an act of everyday resistance. The men sitting in the front are not in official clothes or scrubs and their primary role is to literally bear witness to the violence by physically holding the lifeless bodies of (their own?) children. Taking Donna Haraway’s “staying with the trouble” phrase to its extreme, the civilians in this video are ‘staying in the rubbles’ to bear witness in front of the world and express the conditions of despair and desperation in Gaza.

Works cited

Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Indiana University Press, 1995.

Buck-Morss, Susan. “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin’s Artwork Essay Reconsidered.” October, vol. 62, 1992, pp. 3–41.

CasaInfo. YouTube video of the press conference. October 18, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ufixN2LxXt8&rco=1.

Chamayou, Grégoire. Drone theory. Penguin Books, 2015.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. “Conflicts of Gestures, Conflicts of Images.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, no. 55/56, 2018, file:///Users/au457119/Downloads/lmichelsen,+Conflicts_GeorgesDidi-Huberman-1.pdf

Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. Verso Books, 2021.

Ganguly, Manisha, Emma Graham-Harrison, Jason Burke, Elena Morresi, Ashley Kirk, and Lucy Swan. “Al-Ahli Arab Hospital: Piecing Together What Happened as Israel Insists Militant Rocket to Blame.” The Guardian, October 18, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/18/al-ahli-arab-hospital-piecing-together-what-happened-as-israel-insists-militant-rocket-to-blame.

Hirschhorn, Thomas. Pixel-Collage. 2015, http://www.thomashirschhorn.com/pixel-collage/, 2024.

Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question. https://www.palquest.org/en/highlight/33633/sumud, 2024.

Keenan, Thomas. “Mobilizing Shame.” The South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 103, no. 2, 2004, pp. 435–449, Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/169145.

Ranciére, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. Verso, 2009.

Shullenberger, Geoff. “Baudrillard in Gaza.” Compact Magazine, October 20, 2024, https://www.compactmag.com/article/baudrillard-in-gaza/

Sjöholm, Cecilia. “Images Do Not Take Sides: The Forensic Turn of Images.” The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics, vol. 30, no. 61–62, 2021, pp. 166–170, https://doi.org/10.7146/nja.v30i61- 62.127896.

Steyerl, Hito. “Documentary Uncertainty”. The Long Distance Runner, The Production Unit Archive, No. 72, 2007. http://www.kajsadahlberg.com/files/No_72_Documentary_Uncertainty_v2.pdf

Steyerl, Hito. “In Defence of the Poor Image”. e-flux journal # 10, November 2009, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

Biography

Marie Naja Lauritzen Dias is a Ph.D. Candidate at Aarhus University, School of Communication and Culture affiliated with the department for Art history, Aesthetics and Culture and Museology. Her research centers around war and digital images, the militarization of the everyday life as well as contemporary art and other aesthetic image practices. ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0217-1167