Content Form:APRJA 13 Kendal Beynon: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Kendal Beynon ''' | |||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

<span class="running-header">Zines and Computational Publishing Practices</span> | |||

= Zines and Computational Publishing Practices = | = Zines and Computational Publishing Practices = | ||

| Line 39: | Line 40: | ||

This phenomenon is exemplified in the establishment of web rings online. Coined in 1994 by Denis Howe's EUROPa (Expanding Unidirectional Ring of Pages), the term 'web ring' refers to a navigational ring of related pages. While initially, this practice gained traction for search engine rankings, it evolved into a more social context during the mid-1990s. Personal homepages linked to the websites of friends or community members, fostering a network of interconnected sites. In a space in which zinemakers are in opposition to the dictated mode of media publishing, the web ring offers an alternative way of organising webpages as curated by an individual entity, devoid of hierarchy and innate power structures from an overarching corporation, and places the power of promotion into the hands of the site-builders themselves, and extends to the members of the wider community. | This phenomenon is exemplified in the establishment of web rings online. Coined in 1994 by Denis Howe's EUROPa (Expanding Unidirectional Ring of Pages), the term 'web ring' refers to a navigational ring of related pages. While initially, this practice gained traction for search engine rankings, it evolved into a more social context during the mid-1990s. Personal homepages linked to the websites of friends or community members, fostering a network of interconnected sites. In a space in which zinemakers are in opposition to the dictated mode of media publishing, the web ring offers an alternative way of organising webpages as curated by an individual entity, devoid of hierarchy and innate power structures from an overarching corporation, and places the power of promotion into the hands of the site-builders themselves, and extends to the members of the wider community. | ||

[[File:Fig 4.jpg|thumb| | [[File:Fig 4.jpg|thumb|360px|Figure 4: Factsheet Five, the most common network zine. This zine’s primary function is to share and review other zines as a way to showcase the network, not unlike a web ring.]] | ||

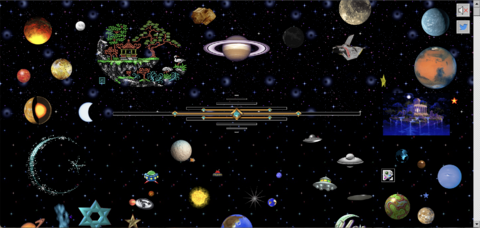

[[File:Fig 5.jpg|thumb| | [[File:Fig 5.jpg|thumb|360px|Figure 5: A selection of early web rings, curated by the owner of the website to promote certain pages that may share similar themes, ideologies, etc.]] | ||

The importance of community, or the more favoured term, network, within the zinemaking practice is held in high regard. Due to its non-geographical nature or sense of place, the zines themselves act as a non-spatial network in which to foster this community. Emulating this concept of the medium as the community space itself, online communities also tend to reside within the confines of the platforms or forums that they operate within. For example, many contemporary internet communities dwell in parts of preexisting mainstream social media platforms such as Discord or TikTok, however, their use of these platforms is a more alternative approach than the intended use prescribed by the developers. Primarily using the gaming platform Discord as an example, countercultural communities create servers in which to disseminate and share resources through building topics within the server to house how-to guides and collect useful links to help facilitate handmade approaches to computational publishing practices. The nature of the server is to promote exchange and to share opinions on a wide array of topics, ranging from politics to typographical elements. These servers are typically composed of amateur users rather than professional web designers, fostering an environment where the swapping of knowledge and skills is encouraged. This continuous exchange of information and expertise creates a common vernacular, a shared language, and a set of practices that are distinct to the community. This not only develops the knowledge made available but also strengthens the bonds within the community, as members rely on and support one another in their collective pursuit of a more democratised digital space. In an online social landscape in which the promotion of self remains at the forefront, this act of distribution of knowledge indicates the existence of a participatory culture as opposed to an individualistic one, all united in shared beliefs and goals. | The importance of community, or the more favoured term, network, within the zinemaking practice is held in high regard. Due to its non-geographical nature or sense of place, the zines themselves act as a non-spatial network in which to foster this community. Emulating this concept of the medium as the community space itself, online communities also tend to reside within the confines of the platforms or forums that they operate within. For example, many contemporary internet communities dwell in parts of preexisting mainstream social media platforms such as Discord or TikTok, however, their use of these platforms is a more alternative approach than the intended use prescribed by the developers. Primarily using the gaming platform Discord as an example, countercultural communities create servers in which to disseminate and share resources through building topics within the server to house how-to guides and collect useful links to help facilitate handmade approaches to computational publishing practices. The nature of the server is to promote exchange and to share opinions on a wide array of topics, ranging from politics to typographical elements. These servers are typically composed of amateur users rather than professional web designers, fostering an environment where the swapping of knowledge and skills is encouraged. This continuous exchange of information and expertise creates a common vernacular, a shared language, and a set of practices that are distinct to the community. This not only develops the knowledge made available but also strengthens the bonds within the community, as members rely on and support one another in their collective pursuit of a more democratised digital space. In an online social landscape in which the promotion of self remains at the forefront, this act of distribution of knowledge indicates the existence of a participatory culture as opposed to an individualistic one, all united in shared beliefs and goals. | ||

| Line 77: | Line 78: | ||

In the contemporary landscape of increasingly AI-generated media, the homogenous nature of digital content can be offset by these DIY practices, which carve out alternative spaces that celebrate diversity and individuality. AI-driven algorithms tend to prioritise content that aligns with dominant trends and consumerist interests (Sarker 158). In contrast, DIY computational publishing practices facilitate the exploration of authenticity and creativity, offering a place for those seeking to express their identities and ideas outside the confines of mainstream digital culture, albeit, by learning a host of technical skills. Ultimately, the intersection of zines and digital DIY culture illustrates a broader movement towards reclaiming creative and communicative agency in an increasingly smooth and familiar digital landscape. By embracing the principles of DIY culture, one can create a digital ecosystem that celebrates individuality, fosters community, and by recognising and supporting these grassroots efforts there is the potential to maintain a democratic and participatory digital culture. | In the contemporary landscape of increasingly AI-generated media, the homogenous nature of digital content can be offset by these DIY practices, which carve out alternative spaces that celebrate diversity and individuality. AI-driven algorithms tend to prioritise content that aligns with dominant trends and consumerist interests (Sarker 158). In contrast, DIY computational publishing practices facilitate the exploration of authenticity and creativity, offering a place for those seeking to express their identities and ideas outside the confines of mainstream digital culture, albeit, by learning a host of technical skills. Ultimately, the intersection of zines and digital DIY culture illustrates a broader movement towards reclaiming creative and communicative agency in an increasingly smooth and familiar digital landscape. By embracing the principles of DIY culture, one can create a digital ecosystem that celebrates individuality, fosters community, and by recognising and supporting these grassroots efforts there is the potential to maintain a democratic and participatory digital culture. | ||

<div class="page-break"></div> | |||

== Works cited == | == Works cited == | ||

Latest revision as of 11:13, 29 October 2024

Kendal Beynon

Zines and Computational Publishing Practices

Zines and Computational Publishing Practices

A Countercultural Primer

Abstract

This paper explores the parallels between historical zine culture and contemporary DIY computational publishing practices, highlighting their roles as countercultural movements within their own right. Both mediums, from zines of the 1990s to personal homepages and feminist servers, provide spaces for identity formation, community building, and resistance against mainstream societal norms. Drawing on Stephen Duncombe's insights into zine culture, this research examines how these practices embody democratic, communal ideals and act as a rebuttal to mass consumerism and dominant media structures. The paper argues that personal homepages and web rings serve as digital analogues to zines, fostering participatory and grassroots networks and underscores the importance of these DIY practices in redefining production, labour, and the role of the individual within cultural and societal contexts, advocating for a more inclusive and participatory digital landscape. Through an examination of both zines and their digital counterparts, this research reveals their shared ethos of authenticity, creativity, and resistance.

Introduction

In the contemporary sphere of machine-generated imagery, internet users seek a space to exist outside of the dominant society using the principles of do-it-yourself (DIY) ideology. Historically speaking, this phenomenon is hardly a novel movement, within the field of subcultural studies, we can see these acts of resistance through zine culture as early as the early 1950s. In Stephen Duncombe's seminal text, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, he describes zines as "noncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their creators produce, publish and distribute by themselves" (Duncombe 10-11). The content of these publications offers an insight into a radically democratic and communal ideal of a potential cultural and societal future. Zines are also an inherently political form of communication. Separating themselves from the mainstream, Elke Zobl states "the networks and communities that zinesters build among themselves are "undoubtedly political" and have “potential for political organization and intervention" (Zobl 6). These feminist approaches to zinemaking allow zinemakers to link their own lived experience to larger communal contexts politicising their ideals within a wider social context, allowing space for alternative narratives and futures. In the book mentioned earlier, in an updated afterword for 2017, Duncombe explicitly states: "One could plausibly argue that blogs are just ephemeral (...) zines".

Continuing this train of thought, this paper puts forward the argument that certain computational publishing practices act as a digital counterpoint and parallel to their physical peer, the zine. Within the context of this research, computational publishing practices refers to personal homepages and self-sustaining internet communities, and feminist server practices. The use of the term 'computational publishing' refers to practices of self-publishing both on a personal and collaborative level, while also taking into consideration the open-source nature of code repositories within feminist servers. Both mediums of a countercultural movement, zines and DIY computational publishing practices offer a space to explore the formation of identity, the construction of networks and communities and also aim to reexamine and reconfigure modes of production and the role of labour within these amateur practices. This paper aims to chart the similarities and connections that link the two practices and explore how they occupy the same fundamental space in opposition to dominant society.

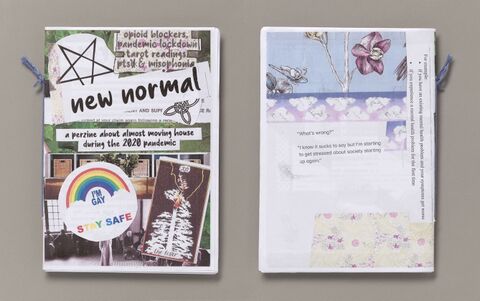

Personalising Identity

Zines are commonly crafted by individuals from vastly diverse backgrounds, but one thing that links them all is their self-proclaimed title of 'losers'. In adopting this moniker, zinesters identify themselves in opposition to mainstream society. Disenfranchised from the prescribed representation offered in traditional media forms, zinemakers operate within the frame of alienation to establish self as an act of defiance. As Duncombe writes, zines are a "haven for misfits" (22). Often marginalised in society, feeling as if their power and control over dominant structures is non-existent, these publications offer an opportunity to make themselves visible and stake a claim in the world through their personal experiences and individual interpretations of the society around them. A particular genre of zine called the personal zine, more commonly known as the 'perzine', is a type of zine that outweighs the subjective over the objective and places the utmost importance on personal interpretation. In other words, perzines aim to express pure honesty on the part of the zinemaker. This often is shown through the rebellion against polished and perfect writing styles in favour of the vernacular and handwritten. The majority of the content of perzines aims to narrate the personal and the mundane, recounting everyday stories as an attempt to shed light on the unspoken. Perzines are often referred to as "the voice of democracy" (Duncombe 29), a way to illuminate difference while also sharing common experiences of those living outside of society, all within the comfort of their bedroom.

With personalisation remaining at the forefront of zine culture as a way to highlight individuality and otherness, the personalisation of political beliefs makes up a large majority of the content present within perzines. In a bid to "collapse the distance between the personal self and the political world" (Duncombe 36), zinemakers highlight the relation between the concept of the 'everyday loser' and the wider political climate they are situated within. As stated, the majority of zinemakers operate outside of mainstream society, so by inserting their own beliefs into the wider political space, they are allowing the political to become personal. This achieves a rebuttal towards dominant institutions through active alienation, revealing the individual interpretation of policies present and situating them in a highly personalised context. This practice of personalising the political also links to the deep yearning zinemakers have for searching for and establishing authenticity within their publications. Authenticity in this context is described as the "search to live without artifice, without hypocrisy" (Duncombe 37). The emphasis is placed upon unfettered reactions that cut through the contrivances of society. This can often be seen in misspelled words, furious scribbling and haphazard cut-outs with the idea of professionalism and perfection being disregarded in favour of a more enthusiastic and raw output. The co-editor of Orangutan Balls, a zine published in Staten Island, only known as Freedom, speaks of this practice of creation with Duncombe, "professionalism – with its attendant training, formulaic styles, and relationship to the market – gets in the way of freedom to just 'express'" (38). There is a deliberate dissent between the ideas of a constructed and packaged identity by the incorporation of nonsensical elements that seek to be seen as an act of pure expression.

As stated in the introduction to this paper, personal webpages and blogs stand in as the digital equivalent of a perzine. In the mid 1990s, a user's homepage served as an introduction to the creator of the site, employing the personal as a tool to relate to their audience. The content of personal pages, not unlike zines, contained personal anecdotes and narrated individual experiences of their cultural situation from the margins of society. While zines adopted cut-and-paste images and text as their aesthetic style, websites demonstrated their vernacular language through the cut-and-pasting of sparkling gifs and cosmic imagery as a form of personalisation. "To be blunt, it was bright, rich, personal, slow and under construction. It was a web of sudden connections and personal links. Pages were built on the edge of tomorrow, full of hope for a faster connection and a more powerful computer." (Lialina and Espenschied 19) Websites were prone to break or contain missing links which cemented the amateurish approach of the site owner. The importance fell on challenging the very web architectures that were in place, pushing the protocols to the limit to test boundaries as an act of resistance. This resistance is mentioned again by Olia Lialina in a 2021 blog post where she articulates to users interested in reviving their personal homepage: "Don't see making your own web page as a nostalgia, don't participate in creating the 'netstalgia' trend. What you make is a statement, an act of emancipation. You make it to continue a 25-year-old tradition of liberation." These homepage expressions can also be seen as a far cry from the template-based web blogs such as Wordpress, Squarespace or Wix which currently dominate the more standardised approach to web publishing in our digital landscape.

Zines also act as a method of escapism or experimentation. Within the confines of the publication, the writers can construct alternative realities in which new means of identity can be explored. Echoing the cut-and-paste nature of a zine, zinemakers collage fragments of cultural ephemera in a bid to build their sense of self, if only for the duration of the construction of the zine itself. These fragments propose the concept of the complexity of self, separate from the neatly catalogued packages prescribed by dominant ideals of contemporary society. Zines, instead, display these multiplicities as a way to connect with their audience, placing emphasis on the flexibility of identity as opposed to something fixed and marketable.

The search for self is prevalent among contemporary internet users, however, usually this takes the form of avatars or interest-based web forums. Avatars, in particular, allow the user to collage identifying features in order to effectively ‘build’ the body they feel most authentic within. Echoing back to the search for authenticity: "What makes their identity authentic is that they are the ones defining it" (Duncombe 45). Zinemakers aim to use zines as a mean to recreate themselves away from the strict confines of mainstream society and instead occupy an underground space in which this can be explored freely. Echoing this idea, the concept of a personal homepage is frequently embraced as a substitute for mainstream profile-based social media platforms prevalent in the dominant culture. Instead of conforming to a set of predetermined traits from a limited list of options, personal homepages offer the chance to redefine those parameters and begin anew, detached from the conventions of mainstream society.

In short, both zines and homepages become a space in which people can experiment with identity, subcultural ideas, and their relation to politics, to be shared amongst like-minded peers. This act of sharing creates fertile ground for a wider network of individuals with similar goals of reconstructing their own identities, while also encouraging the formulation of their own ideals from the shared consciousness of the community. While zines are the fruit of individuals disenfranchised from the wider mainstream society, they become a springboard into larger groups merging into a cohesive community space.

Building and Sharing the Network

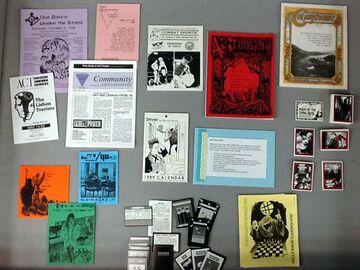

Amongst the alienation felt from being underrepresented in the dominant societal structures, it comes as little surprise that zinemakers often opt for creating their own virtual communities via the zines they publish. In an interview with Duncombe, zinemaker Arielle Greenberg stated "People my age... feel very separate and kind of floating and adrift", this is often counteracted by integrating oneself within a zine community. Traditionally within zine culture, this takes the form of letters from readers to writers, and reviews of other zines that become the very fabric, or content, of the zine themselves. This allows the zine to transform into a collaborative space that hosts more than a singular voice, effectively invoking the feeling of community. This method of forming associations creates an alternative communication system, also through the practice of zine distribution itself. For example, one subgenre of zines is aptly named 'network zines', and their contents entirely comprise reviews of zines recommended by their readership.

This phenomenon is exemplified in the establishment of web rings online. Coined in 1994 by Denis Howe's EUROPa (Expanding Unidirectional Ring of Pages), the term 'web ring' refers to a navigational ring of related pages. While initially, this practice gained traction for search engine rankings, it evolved into a more social context during the mid-1990s. Personal homepages linked to the websites of friends or community members, fostering a network of interconnected sites. In a space in which zinemakers are in opposition to the dictated mode of media publishing, the web ring offers an alternative way of organising webpages as curated by an individual entity, devoid of hierarchy and innate power structures from an overarching corporation, and places the power of promotion into the hands of the site-builders themselves, and extends to the members of the wider community.

The importance of community, or the more favoured term, network, within the zinemaking practice is held in high regard. Due to its non-geographical nature or sense of place, the zines themselves act as a non-spatial network in which to foster this community. Emulating this concept of the medium as the community space itself, online communities also tend to reside within the confines of the platforms or forums that they operate within. For example, many contemporary internet communities dwell in parts of preexisting mainstream social media platforms such as Discord or TikTok, however, their use of these platforms is a more alternative approach than the intended use prescribed by the developers. Primarily using the gaming platform Discord as an example, countercultural communities create servers in which to disseminate and share resources through building topics within the server to house how-to guides and collect useful links to help facilitate handmade approaches to computational publishing practices. The nature of the server is to promote exchange and to share opinions on a wide array of topics, ranging from politics to typographical elements. These servers are typically composed of amateur users rather than professional web designers, fostering an environment where the swapping of knowledge and skills is encouraged. This continuous exchange of information and expertise creates a common vernacular, a shared language, and a set of practices that are distinct to the community. This not only develops the knowledge made available but also strengthens the bonds within the community, as members rely on and support one another in their collective pursuit of a more democratised digital space. In an online social landscape in which the promotion of self remains at the forefront, this act of distribution of knowledge indicates the existence of a participatory culture as opposed to an individualistic one, all united in shared beliefs and goals.

As zinemakers often come from a place of disparity or identify as the other (Duncombe 41), it is precisely this relation of difference, that links these zine networks together, sharing both their originality but also their connectedness through shared ideals and values. Through this collaborative approach, "a true subculture is forming, one that crosses several boundaries" (Duncombe 56). This method of community helps propagate both individualities while simultaneously sharing the very amongst peers, simultaneously allowing their own content to gain the same treatment in the future.

The FOSS movement present in feminist servers also speaks to the ethics of open source software and the free movement of knowledge between users. FOSS, or Free Open Source Software champions transparency within publishing allowing users the freedom to not only access the code but also enact changes to it for their own use (Stallman 168). In Adele C Licona’s book, Zines in Third Space, she also acknowledges the use of bootlegged material: "The act of reproduction without permission is a tactic of interrupting the capitalist imperative for this knowledge to be produced and consumed only for the profit of the producer; it therefore serves to circulate knowledge to nonauthorized consumers" (128). This manner of making stems from a culture of discontent against dominant power structures that control what and how that media is published. Zines are an outlet to express this discontent under their own restrictions and method of reaching their readers while uniting with a wider network of publishers doing the same.

Though zines exist on the fringes of society, their core concerns resonate universally throughout the zine network: defining individuality, fostering supportive communities, seeking meaningful lives, and creating something uniquely personal. Zines act as a medium for a coalitional network that breeds autonomy through making while actively encouraging the exchange of ideas and content. Dan Werle, editor of Manumission Zine states his motivations for zines as a medium for his ideas: "I can control who gets copies, where it goes, how much it costs, its a means of empowerment, a means of keeping things small and personal and personable and more intimate. The people who distribute my zines I can call and talk to... and I talk directly to them instead of having to go through a long chain of never-ending bourgeoisie" (Duncombe 106). With this idea of control firmly placed in the foreground for zinemakers, these zines' aesthetic frequently reflects this, with the hands of the maker is evident in the construction of the publication through handwriting and handmade creation. The importance of physically involving the creator in the process of making zines demonstrates the power the user has over the technological tools used to aid the process, closing the distance between producer and process. Far from only addressing the ethics of the DIY ideals abstractly, zines become the physical fruits of an intricate process, thus encouraging others to get involved and do the same.

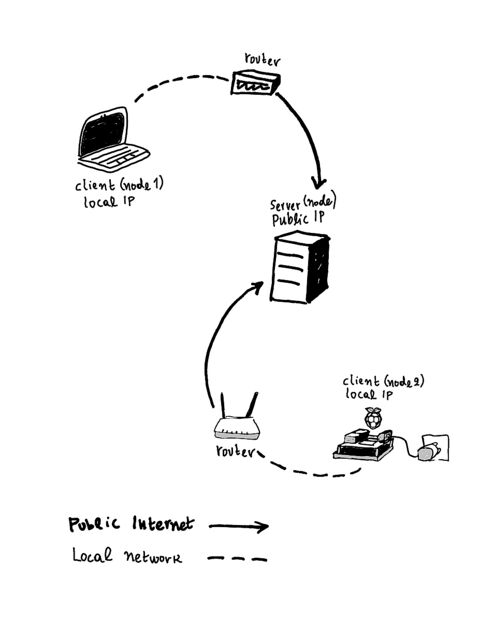

Paralleling the materiality of the medium, feminist servers emphasise the technology needed to build and host a server. Using DIY tools such as microcontrollers and various modifications to showcase the inner workings of an active server, the temporal nature of the abstract server is revealed. In this, the vulnerabilities of the tool are also exposed, microcontrollers crash and overheat, de-fetishising the allure of a cloud-based structure, thus, once again bridging the gap between the producer and the process.

Additionally to the question of labour practices in the dominant society, the concept of mass consumption is of real concern to those involved in zine culture. In the era of late capitalism, society has swiftly shifted towards mass-market production, leading to a surge in consumerism. Once a lifestyle made solely available to the wealthy upper classes, mass production of everyday commodities has democratised consumption, making products widely available through extensive marketing to the masses. Historically, consumers felt a kinship with products due to their handmade quality, however, this has diminished in the current market substantially, instead fetishising the hordes of cheaply made objects under the guise of luxury.

Zines are an attempt to eliminate this distance between consumer and maker by rejecting this prescribed production model. Celebrating the amateur and handmade, zines reconnect the links between audience and media through de-fetishising elements of cultural production and revealing the process in which they came to be. Yet again, using alienation as a tool, zinemakers reject their participation in the dominant consumerist model and instead opt for active engagement in a participatory mode of making and consuming. The act of doing it yourself is a direct retaliation to how mainstream media practices are attempting to envelope its audiences, through arbitrary attempts at representation, "because the control over that images resides outside the hands of those being portrayed, the image remains fundamentally alien" (Duncombe 127).

This struggle for accurate representation speaks back to some of the concepts stated in the first part of this paper, namely, how identity is formed and defined. With big-tech corporations headed solely by cisgender white men (McCain), feminist servers aim to diversify the server through their representation of the non-dominant society by sharing knowledge freely. Information is made more widely accessible for marginalised groups beyond the gaze of the dominant power structure and for those with less stable internet connections usually overfed with the digital bloat that accompanies mainstream social platforms. By sharing in-depth how-to guides for setting up their own servers, these platforms not only democratise the internet but also empower individuals to build and sustain more grassroots communities. This accessibility encourages a shift away from reliance on mainstream big-tech corporations, fostering a more inclusive and participatory digital landscape. By enabling users to take control of their own online spaces, these servers promote autonomy, privacy, and a sense of collective ownership.

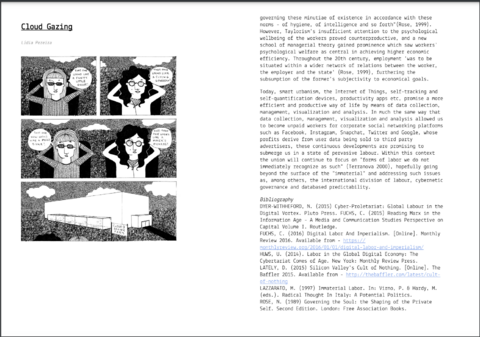

Zines, similarly, propose an alternative to consumerism in the form of emulation, by encouraging the participatory aspect of zine culture through knowledge sharing, and actively supporting what would usually be seen as a competitor in the dominant consumer culture, readers are encouraged to emulate what they read within their individual beliefs creating a collaborative and democratic culture of reciprocity. The very act of creating a zine and engaging in DIY culture generates a flow of fresh, independent thought that challenges mainstream consumerism. By producing affordable, photocopied pages affording everyday tools, zines counter the fetishistic archiving and exhibition practices of the high art world and the profit-driven motives of the commercial sector: "Recirculated goods reintroduce commodities into the production and consumption circuit, upsetting any notions that the act of buying as consuming implies the final moment in the circuit." (Licona 144) Additionally, by blurring the lines between producer and consumer, they challenge the dichotomy between active creator and passive spectator that remains at the forefront of mainstream society. As well as de-fetishising the form of a publication, they present their opposition and dissonance by actively rejecting the professional and seamless aesthetics that more commercial media objects tend to possess.

This jarring nature of rough and ready against progressively homogenous visuals demands the audience's attention and reflects the disorganisation of the world rather than appeasing it. Commercial culture isolates one from reciprocal creativity through its black-boxing of the process, while zines initially employ alienation to later embrace one as a collaborative equal. The medium of zines and feminist servers isn't merely a message to be absorbed, but a suggestion of participatory cultural production and organisation to become actively engaged in.

Conclusion

From the connections outlined above, the exploration of DIY computational publishing practices reveals significant parallels to the formation of zine culture, both serving as mediums for personal expression, community building, and resistance against dominant societal norms. By examining personal homepages, web rings, and feminist servers, this paper demonstrates how these digital practices echo the democratic and grassroots ethos of traditional zines. These platforms not only offer individuals a space to construct and share their identities but also foster inclusive communities that challenge mainstream modes of production and consumption.

Web rings facilitate a space of digital collectivism that mirrors the collaborative spirit of zine networks, these interconnected websites create a web of shared interests and mutual support, reminiscent of the way zines often feature contributions from various authors and artists within a community. This networked approach not only enhances visibility for individual creators but also strengthens the sense of community by fostering a culture of sharing and collaboration. The decentralised nature of web rings contrasts with dominant structures in play of mainstream social media platforms, where algorithms dictate the visibility and reach of content, thereby reinforcing existing power dynamics and limiting the diversity of voices from marginalised groups.

A feminist server reveals the radical potential of DIY computational publishing by explicitly aligning technological practices with feminist and anti-patriarchal principles and offer a space for these communities to connect and share resources. This ethos of mutual aid and empowerment is deeply rooted in the DIY tradition, reflecting the zine culture’s emphasis on community-driven knowledge production and dissemination. By reclaiming the tools of production, individuals can subvert the power structures that typically regulate mainstream digital spaces, creating platforms that reflect their values and ideals instead. While these connections and similarities reveal themselves through their ethos and approach, it should be acknowledged that the computational counterpoints mentioned within this paper come with a steep learning curve in technical literacy and undeniable privilege to create these tools in the first place. Even within the zine community itself, the openness and accessibility of the internet still exposes a digital divide resulting in the majority of zines remaining as physical publications (Zobl 5).

In the contemporary landscape of increasingly AI-generated media, the homogenous nature of digital content can be offset by these DIY practices, which carve out alternative spaces that celebrate diversity and individuality. AI-driven algorithms tend to prioritise content that aligns with dominant trends and consumerist interests (Sarker 158). In contrast, DIY computational publishing practices facilitate the exploration of authenticity and creativity, offering a place for those seeking to express their identities and ideas outside the confines of mainstream digital culture, albeit, by learning a host of technical skills. Ultimately, the intersection of zines and digital DIY culture illustrates a broader movement towards reclaiming creative and communicative agency in an increasingly smooth and familiar digital landscape. By embracing the principles of DIY culture, one can create a digital ecosystem that celebrates individuality, fosters community, and by recognising and supporting these grassroots efforts there is the potential to maintain a democratic and participatory digital culture.

Works cited

Carr, C. "Bohemia Diaspora," Village Underground, 4 February 1992.

Carmona, C. "Keeping the Beat: The Practice of a Beat Movement", Texas A&M University, 2012.

Casey, C. "Web Rings: An Alternative to Search Engines", Vol 59, No 10 College & Research Libraries News, 1998, 761-763.

Duncombe, S. Notes from underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Microcosm Publishing, 2017.

Hebdige, D. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. Routledge, 1979.

Howe, D. "Expanding Unidirectional Ring Of Pages." Denis’s Europa Page, 22 Dec. 1994, foldoc.org/europa.html.

Karagianni, M, Wessalowski, N. "From Feminist Servers to Feminist Federation," ARPJA Vol. 12, Issue 1, 2023.

Lialina, O. "Olia Lialina: From My to Me." INTERFACECRITIQUE, 2021, https://interfacecritique.net/book/olia-lialina-from-my-to-me/.

Lialina, O., Espenschied, D. and Buerger, M. Digital Folklore: To computer users, with love and respect. Merz & Solitude, 2009.

Licona, A.C. Zines in Third Space: Radical Cooperation and Borderlands Rhetoric. SUNY Press, 2013.

McCain, A. "40 Telling Women In Technology Statistics [2023]: Computer Science Gender Ratio" Zippia.com. Oct. 31, 2022, https://www.zippia.com/advice/women-in-technology-statistics/.

Sarker, I.H. "AI-Based Modeling: Techniques, Applications and Research Issues Towards Automation, Intelligent and Smart Systems." SN Comput Sci. 3, 158, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01043-x.

Stallman, R. "Floss and Foss - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation, [A GNU head]," 2013. https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/floss-and-foss.en.html (Accessed: 17 May 2024).

Stallman, R. Free as in Freedom (2.0): Richard Stallman and the Free Software Revolution, Free Software Foundation, 2010.

Steyerl, H. "Mean Images," New Left Review 140/141, March–June 2023, New Left Review. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii140/articles/hito-steyerl-mean-images (Accessed: 31 October 2023).

Systerserver, https://systerserver.net/ (Accessed: 17 May 2024).

Zobl, E. "Cultural Production, Transnational Networking, and Critical Reflection in Feminist Zines." Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 2009. https://doi.org/40272280.

Biography

Kendal Beynon (UK) is a Rotterdam-based artist and PhD researcher at CSNI in partnership with The Photographers’ Gallery, London. Her work is situated in the realm of experimental publishing and internet culture. Completing a bachelor’s degree in the UK in Music Journalism in 2013, she went on to receive her MA degree in Experimental Publishing from the Piet Zwart Instituut, Rotterdam. She also is heavily engaged with the zine-making community by hosting workshops and co-organising the Rotterdam-based zine festival, Zine Camp, and creating a community of old web aficionados at Dead Web Club.