Toward a Minor Tech:Fartan: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (83 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | |||

'''Teodora Sinziana Fartan''' | |||

= Rendering Post-Anthropocentric Visions:<br>Worlding As a Practice of Resistance = | |||

[[ | <span class="running-header">Rendering Post-Anthropocentric Visions: Worlding As a Practice of Resistance</span> | ||

[[ | |||

== Abstract == | |||

This paper formulates a strategic activation of speculative-computational practices of ''worlding'' by situating them as networked epistemologies of resistance. Through the integration of Deleuze and Guattari's concept of a ‘minor literature’ with the distributed software ontologies of algorithmic worlds, a tentative politics for thinking-''with'' worlds is mapped, anchored in the potential of worlding to counter the dominant narratives of our techno-capitalist cultural imaginary. With particular attention to the ways in which the affordances of software can become operative and offer alternative scales of engagement with modes of being-otherwise, an initial theoretical mapping of how worlding operates as a multi-faceted and critical storytelling practice is formulated. | |||

<div class="page-break"></div> | |||

== Introduction == | |||

Emanating from the fog of late techno-capitalism, the contours of a critical techno-artistic practice are starting to become visible - networked, immaterial and often volumetric, practices of ''worlding'' surface as critical renderings concerned with speculatively envisioning modes of being otherwise through computational means. By intersecting software and storytelling, these practices cultivate more-than-human assemblages that foreground possible world instances - worlding, thus, becomes politically charged as a networked epistemology of resistance, where dissent is enabled through the rendering of alternative knowledge systems and relational entanglements existing beyond the ruins of capitalism. | |||

In the ontological sense, ''practices of worlding'' materialise as algorithmic portals into fictional terrains where alternative modes of being and knowing are envisioned; they refuse to adopt a totalising view of the megastructure of capitalism’s cultural imaginary and instead opt to zoom in onto the cracks appearing along its edges, where other narrative possibilities are starting to sprout and multiply. Through the evocative affordances of software, practices of worlding teleport us forwards, amidst the ruins of the Anthropocene, where “unexpected convergences” emerge from the debris of what has passed (Tsing 205). | |||

In their quests for speculative possibility, world-makers are dislodging existing hi-tech systems and platforms from their conventional economical or institutional roles and repurposing them as technologies of possibility which seek to de-centre the dominant narratives of the Western cultural imagination. A reversing of scales therefore occurs, where 'high tech' becomes deterritorialized and mobilised towards the objectives of a 'minor tech', which seeks to counter the universal ideals embedded in technologies through foregrounding "collective value" (Cox and Andersen 1). | |||

Consequently, recent years have seen an increased interest in the (mis)use of software such as game engines or machine learning for the artistic exploration of crossovers between the technological, the ecological and the mythical; specifically, through the emergence of increasingly capable and accessible platforms such as Unreal Engine and Unity, game engines have become the creative frameworks of choice for conjuring worlds due to their potential for rapid prototyping and increased capacity of rendering complex, real-time virtual imaginaries. Whilst worlding can exist across a spectrum of algorithmically-driven techniques and systems, it is most often encountered through (or integrates within its technological assemblage) the game engine, as we will see in the course of this paper. | |||

In what follows, I aim to at once activate an initial cartography of ‘worlding’ as an emergent techno-artistic praxis and propose a tentative politics for thinking not only ''through'', but also ''with'' worlding as a process that can facilitate ways of imagining outside the rigid narratives of techno-scientific capitalism. | |||

I propose that it is particularly through its refiguring of computational methodologies that worlding positions itself as an exercise in creative resistance. Through a refiguration of technology as a speculative tool, worlding offers a potent method for thinking outside of our fraught present by algorithmically envisioning radically different ontologies - these modes of being-otherwise, I contend, also bring forth a new epistemological and aesthetic framework rooted in both the affordances of the technological platforms used for their production and the relational assemblages at their core: the network, in itself, becomes unearthed throughout this paper as the essence of algorithmic world instances and is proposed as a mode of conceptualisation for these practices. | |||

Within the context of political resistance, by approaching these algorithmically-rendered worlds through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of a 'minor literature' (16), we can trace the emergence of ''minor worlds'' as potent and powerful assemblages for countering the majority worlds of platform capitalism and their dominant socio-cultural narratives - what can these minor worlds reveal about more-than-human collaborations and the critical role of software within speculative practices? How do they become operative as instruments for de-centering the master narratives of our present? What alternative knowledges do they draw upon within their ontologies and what potentialities do they open up for encountering these? | |||

Throughout this paper, the worlds conjured by artists such as Ian Cheng, Sahej Rahal, Keiken and Jenna Sutela will be drawn on in order to gain insight into the ways in which worlding at once becomes operative as a form of social and political critique and activates a process of collective engagement with potent acts of futuring, where a co-existence together and alongside the non-human is foregrounded. | |||

== Worlding in the age of the anthropocene == | |||

Today, there seems to be a widespread view that we are living at the end - of liberalism, of imagination, of time, of civilisation, of Earth; engulfed in the throes of late capitalism, conjuring a possible alternative seems exceptionally out of grasp. In his novel ''Pattern Recognition'', which constitutes a reflection on the human desire to detect patterns and meaning within data, William Gibson formulates a statement that rings particularly relevant when superimposed onto our present state: | |||

<blockquote>we have no idea, now, of who or what the inhabitants of our future might be. In that sense, we have no future. Not in the sense that our grandparents had a future, or thought they did. Fully imagined cultural futures were the luxury of another day, one in which 'now' was of some greater duration. For us, of course, things can change so abruptly, so violently, so profoundly, that futures like our grandparents' have insufficient 'now' to stand on. We have no future because our present is too volatile […] We have only risk management. The spinning of the given moment's scenarios. Pattern recognition. (57)</blockquote> | |||

Here, Gibson makes reference to the near-impossibility of imagining a clear-cut future in a present that is marred by ecological, political and social unrest - I contend that this fictional excerpt is distinctly illustrative of the affective perception of life within the age of the anthropocene, where the volatility of the present, caused by the knowledge that changes on a planetary scale are imminent, ensures that a given future can no longer be predicted or visualised. Without the ability to rationally deduce a logical outcome, what we, too, are left with is a sort of ''pattern recognition'' - an attempt to find patterns for ways of being and knowing that can become the scaffold for visions of the future; as Gibson foregrounds, today, rather than being logically deducible, the future needs to be sought through the uncovering of new patterns. | |||

Just like Gibson's character, we do not know what kind of more-than-human assemblages will inhabit our future states - and it is precisely here that this act of pattern recognition intersects with the core agenda of worlding: how can we envision patterns of possible futures using computation? Within our own contemporary context, where asymmetrical power structures, surveillance capitalism and the threat of climate change deeply complicate our ability to think of possible outcomes, where can new patterns emerge? | |||

In the wake of the Anthropocene, feminist critical theory has launched several calls for seeking such patterns with potential to provide a foothold for experiments in imagining future alternatives: from Stenger’s bid to cultivate “connections with new powers of acting, feeling, imagining and thinking” (24), to Haraway’s request for critical attention to “what worlds world worlds” ("Staying with the trouble" 35) and LeGuin’s plea for a search for the ‘other story’ (6) - an alternative to the linear, destructive and suffocating narratives regurgitated perpetually within the history of human culture. We can, therefore, trace the emergence of a collective utterance, an incantation resonating across feminist epistemologies, emphasising the urgency of developing patterns for thinking and being otherwise - as Rosi Braidotti asks, “how can we work towards socially sustainable horizons of hope, through creative resistance?” (156) | |||

In a reality marred by a crisis of imagination, where “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than that of capitalism” (Fisher 1), casting one’s imagination into a future that refuses the master narratives of capitalism is no easy feat, and requires, as Palmer puts it, a "cessation of habitual temporalities and modes of being" ("Worlding") in order to open up spaces of potentiality for speculative thinking - to think outside ourselves, towards possible future alternatives, has therefore become a difficult exercise within the current socio-political context. | |||

We can then identify the most crucial question for the agenda of worlding: what comes after the end of our world (understood here as capitalist realism (Fisher 1))? Or, better phrased, what can exist outside the scaffolding of reality as we know it, dominated by asymmetric power structures, infused with injustice, surveilled by ubiquitous algorithms and continuously subjected to extractive practices? And what kind of technics and formats do we need to visualise these modes of being otherwise? | |||

Techno-artistic worlding practices attempt to intervene precisely at this point and open up new ways of envisioning through their computational nature - which, in turn, produces new formats of relational and affective experience through the generative and procedural affordances of software. The world-experiments that emerge from these algorithmic processes constitute hybrid assemblages of simulated spaces, fictive narratives, imagined entities and networked entanglements - collectively, they speculatively engage with the uneven landscape of being-otherwise, its multiplicities and many textures and viscosities. | |||

== Listening to the operational logic of computationally-mediated worlds == | |||

To begin an analysis of how worlding attempts to engage with the envisioning of alternatives, we'll first turn to Donna Haraway, who further instrumentalizes the idea of patterning introduced earlier through Gibson: when situating worlding as an active ontological process, she says that "the world is a verb, or at least a gerund; worlding is the dynamics of intra-action [...] and intra-patience, the giving and receiving of patterning, all the way down, with consequences for who lives and who dies and how" ("SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far" 8). By making the transition from noun to verb, from object to action, worlds and patterns become active processes of ''worlding'' and ''patterning''. In Haraway's theorising of speculative fabulation, patterning involves an experimental processes of searching for possible "organic, polyglot, polymorphic wiring diagrams" - for a possible fiction, whilst worlding encapsulates the act of conjuring a world on the basis of that pattern ("SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far" 2). Furthermore, Haraway situates worlding as a practice of collective relationality, of intra-activity between world-makers and world-dwellers, as well as between world and observer, through a networked process of exchange. It is important to note that worlding, to Haraway, is far from apolitical: she evidences its relevance by defining it as a practice of life and death, which has the potential to engage in powerful formulations of alternatives - acts which might be crucial in establishing actual future states. As she argues, “revolt needs other forms of action and other stories of solace, inspiration and effectiveness” ("Staying with the Trouble" 49) | |||

To gravitate towards an understanding of these other stories, we'll approach worlding in context through the eyes of Ian Cheng, an artist working with live simulations that explore more-than-human intelligent assemblages. Cheng defines the world, as “a reality you can believe in: one that promises to bring about habitable structure from the potential of chaos, and aim toward a future transformative enough to metabolise the pain and pleasure of its dysfunction” ("Worlding Raga") - a world, in this perspective, needs to be an iteration of the possible, one that presents sufficient transformative power for existing otherwise; the referencing of 'belief' is also crucial here as, within capitalist realism, where all "beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration" (Fisher 8), its very activation becomes and act of revolt. | |||

Of worlding, Cheng says that it is “the art of devising a World: by choosing its dysfunctional present, maintaining its habitable past, aiming at its transformative future, and ultimately, letting it outlive your authorial control” ("Worlding Raga") - the world-maker, therefore, does not only ideologically envision a possible reality, but also renders it into existence through temporal and generative programming. Cheng balances this definition within the context of his own practice concerned with emergent simulations, where authorship becomes a distributed territory between the human and more-than-human. | |||

It is important to note that Cheng refuses to ascribe any particular form, medium or technology as an ideal template of worlding - rather, discreetly and implicitly, Cheng’s definition evokes the operational logic of algorithms by referencing the properties of intelligent and generative software systems. The definiton's refusal of medium-specificity mirrors the multiplicity of ways in which algorithms can world: whilst many of these worlds initially unfold as immersive game spaces (and then become machinima, or animated films created within a virtual 3D environment (Marino 1) when presented in a gallery environment), satellite artefacts can emerge from a world's algorithmic means of production, often becoming a physical manifestation of that world's entities - taking shape, for example, as physical renditions of born-digital entities, as seen in the sculptural works as that emerge from Sahej Rahal's world, ''Antraal'', where figures of the last humans, existing in a post-species, post-history state, are recreated outside of the gamespace. | |||

[[File:Antraal.jpg|thumb|400px|Figure 1: Exhibition view of ''Antraal'' by Sahej Rahal. ''Feedback Loops'', 7 Dec 2019–15 Mar 2020, ACCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the artist.]] | |||

Transgressions of the fictional world into real-space can take a variety of shapes, depending on the politics and intentions of that world: other examples of worlds spilling out of rendered space and into reality are Keiken's ''Bet(a) Bodies'' installation, where a haptic womb is proposed as an emphatic technology for connecting with a more-than-human assemblage of animal voices and Ian Cheng’s BOB Shrine App that accompanied his simulation ''BOB (Bag of Beliefs)'' in its latter stages of development, through which the audience can directly interact with the AI by sending in app 'offerings', which impress what Cheng terms 'parental influence' on BOB, in order to offset its biases. | |||

Consequently, it becomes apparent that practices of worlding are governed by an inherent pluralism - due to this multiplicity of possible tools and algorithms that can operate within the scales of worlding, we are in need of an open-ended definition that can encapsulate commonalities whilst also allowing for plurality of form - I propose here to focus on the unit operations making these worlds possible. From gamespace environments to haptic-sonic assemblages or interactive AI, the common denominator of all these artefacts does not lie in their media specificity, but rather in their software ontology and its procedural affordance, defined by Murray as "the processing power of the computer that allows us to specify conditional, executable instructions" ("Glossary"). | |||

A working definition for worlding that integrates unit operations with speculative logic can be therefore traced: worlding is a sense-making exercise concerned with metabolising the chaos of possibility into new forms of order through the relational structures enabled by procedural affordances. It involves looking for the logic that threads a world together and then scripting that logic into networked algorithms that render it into being. To world with algorithms is to dissent from the master narratives of capitalism by critically rendering habitable alternatives. | |||

Crucial to this definition is an understanding of software as a cultural tool - its procedural affordances, as Murray reflects, have "created a new representational strategy, [...] the simulation of real and hypothetical worlds as complex systems of parameterised objects and behaviours" ("Glossary"). To understand the operative logic that enables procedural worlds, a similar pluriversal analytical model to that proposed by de la Cadena and Blaser (4) becomes necessary for conceiving these ecologies of practice - I propose, therefore, a conceptual model for understanding the symbolic centre of worlding by turning to the ways in which software itself creates and communicates knowledge: the network. | |||

Reflecting on Tara McPherson's assertion that “computers are themselves encoders of culture” (36), being able to produce not only representations but also epistemologies, one must wonder, then: in the context of of algorithmic worlds, how do their networked cores become culturally charged? What kind of new knowledges become encoded in their procedural affordances? | |||

== Thinking with networks: an epistemic shift towards relationality == | |||

Another vector through which the nature of worlding can be theoretically approached emerges from Anna Munster’s theorising of networks, particularly her definition of ‘network anaesthesia’ - a term she develops to suggest the numbing of our perception towards networks, making their unevenness and relationality obscure (3). A similar anaesthesia can be identified when working with platformised tools such as game engines, where, as Freedman points out, "the otherwise latent potential of code, found in its modularity, is readily sealed over" - due to code becoming concretized into objects, the computational inner workings of certain aspects become blackboxed (Anable, 137). The trouble with engines is that, in our case, they promote a worlding anaesthesia, where the web of relations at play within that world instance is not immediately apparent due to their obscuring of software. | |||

Wendy Chun speaks of a similar paradox to that of the network anaesthesia by referencing the ways in which computation complicates both visuality and transparency. Visuality in the sense of the proliferation of code objects that it enables, and transparency in the sense of the effort of software operations to conceal their input/output relationalities - visualising the network, therefore, becomes an exercises in revealing the inner workings of worlds, one that resists the intentional opacity of the platforms that become involved in their genesis. | |||

Munster, too, calls for more heightened reflective and analytical engagements with “the patchiness of the network field” (2) by making its relations visible (and implicitly ''knowable'') through diagrammatic processes. She contends that, in order to decode the networked artefact, we must attempt to understand the forces at play within it from a relational standpoint: | |||

<blockquote>We need to immerse ourselves in the particularities of network forces and the ways in which these give rise to the form and deformation of conjunctions — the closures and openings of relations to one another. It is at this level of imperceptible flux — of things ''unforming'' and ''reforming'' relationally — that we discover the real experience of networks. This relationality is unbelievably complex, and we at least glimpse complexity in the topological network visualisation. (3)</blockquote> | |||

For Munster, therefore, the structuring of relations and their interconnectedness is paramount to any attempt at making sense of the essence of a software artefact or system. This relational perspective towards networked assemblages opens up a potent line of flight for the conceptualisation of the processes involved in the rendering of worlds - if the centre of a world is a network, that can in itself sustain a number of inputs and outputs of varying degrees of complexity, interlinked in a constant state of flux, then any attempt to understand such a world must involve conceptual engagement with the essence of the network, or the processes through which relations open and close and produce these states of flux. Engagement with algorithmic worlds, therefore, moves from the perceptual into the diagrammatic, from a practice of observation to one of sense-making, involving not only visualisations but also a certain computational ''knowing'', an understanding of relations and flows. I argue here that engagement with worlds necessitates an increased type of cognitive engagement, one that allows us to understand the object of discussion differently, through a foregrounding of relational exchanges. | |||

I propose a turn towards cartographing the relations that operate within a world on an affective level, due to the spaces of evocative possibility opened up by a world's procedural affordances. Murray draws on EA's 1986 advert asking "Can a computer make you cry?" to reflect on the need for increased critical attention to be given to the ways in which affective relations form within a procedural space; she argues that "tears are an appropriate measure of involvement because they are physiological and suggest authenticity and depth of feeling" (84), but clarifies that it is precisely the visceral aspect of crying that is of interest - the focus is not on "sad content, but compellingly powerful and meaningful representation of human experience" (85). She observes that, in the domain of video games, whilst there are some experiments with instilling emotion in viewers, these are not yet complex structures of feeling; she calls, therefore, for the development of computational experiences that constitute "compellingly powerful and meaningful representation of human experience", highlighting the crucial importance of affect. By further extending this idea into the territory of worlding, it becomes apparent that structures of feeling are essential for creating worlds that engage in resistance, and identify Murray's call as a core element on the agenda of worlding. | |||

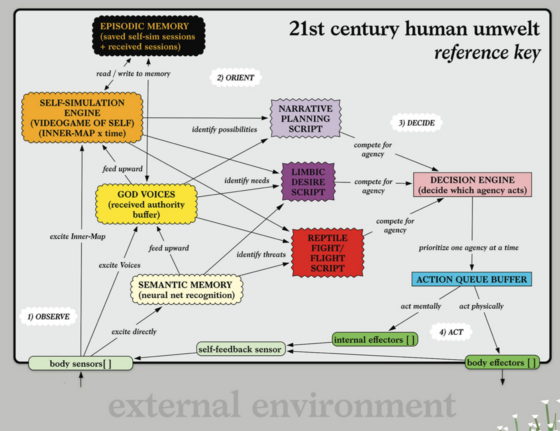

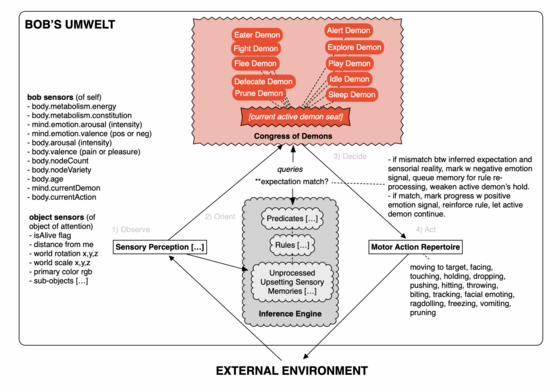

Today, we are already seeing experiments in ‘knowing’ networks emerging - we'll circle back to Cheng here, who seems to have stablished a practice of conceptually diagramming his work on BOB (Bag of Beliefs) - one that does not simply relate input to output or technically map, but also pays attention to producing a cartography of the affective relations scripted into BOB's world. By showing increased tendencies towards engagement with not only the network itself, but also the ''networking'', Cheng traverses the crucial space between the perceived (the immediate) and the perceptual (the more esoteric, affectively charged circulations of data within a system), as seen in the examples of Figures 2 and 3, which do not seek to formally capture the elements of a network assemblage, but rather, to create a “topological surface” (Massumi 751) for the experience of that world. | |||

[[File:Figure 2. Ian Cheng, excerpt from Emissaries Guide, 2017. (Image courstesy of the artist).png|thumb|560px|Figure 2: "21st century human wmwelt" diagram by Ian Cheng, from ''Emissaries Guide'', 2017. Image courtesy of the artist.]] | |||

[[File:IanCheng BOB'sUmwelt.png|thumb|560px|Figure 3: Ian Cheng's ''Emissary Forks at Perfection Map''. Pillar Corrias London, 2015. Image courtesy of the artist.]] | |||

As Munster inflects, the goal is “not to abstract a set of ideal spatial relations between elements but to follow visually the contingent deformations and involutions of world events as they arise through conjunctive processes” (5) - in Cheng’s diagram, we see a phenomenological and epistemological topology of the networking processes at play, where affective relations are beginning to be mapped alongside algorithmic diagramming - in the spaces between memory, narrative and desire, a spectrum of relational flows and possibilities emerge. Demonstrating the essence of the network through its flow of relations, Cheng attempts to diagram the simulation across both affective and technical scales. | |||

Thinking ''with'' (rather than simply through) worlding, can, therefore, produce an affective networked epistemology where an increased attention to relationality can cultivate new ways of both seeing and understanding beyond the purely machinic. A question of scale emerges here: how do affective and technological scales become intertwined within computer-mediated worlds? When thinking-''with'' worlds, care needs to be taken to address the affective scale along the technical one - how do these scales have the potential to affect one another and the much larger scale of human experience? This vector of research constitutes a significantly larger line of enquiry, one that I will delegate to worlding's future research agenda - for now, I'll return to Murray's note on computers and tears and ask: could worlds make us cry? | |||

== Rendering resistance: the emergence of minor worlds == | |||

In an age of anxiety underscored by invasive politics and ubiquitous algorithmic megastructures, the major technologies of the present such as artificial intelligence, game engines, volumetric rendering software and networked systems are employed in the service of extractive and opaque practices. However, as Foucault proclaims, “where there is power, there is resistance” (95): when dislodged from their socio-economical frameworks and taken amidst the ruins of the same reality, crumbling under the weight of late techno-capitalism, these technologies can also become an instrument of dissent - to simulate a world volumetrically, epistemologically and relationally becomes an exercise in (counter)utilising the major technologies of the present in order to produce tactics that lead out of these ruins and into a future dominated by new, pluralistic, decentralised and distributed agencies taking shape according to “ecological matters of care” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 24). | |||

To resist, here, means to engage with the broader questions of power and refusal within the context of software practices. Within practices of worlding, this refusal of capitalism’s master narratives in favour of imagining otherwise takes shape through a more-than-human entanglement with technologies that are capable of procedurally rendering a glimpse into alternative modes of being through simulation. As LeGuin proposes, technology can be dislodged from the logic of capitalism and refigured as a cultural carrier bag (8); in this sense, she envisions this refiguration as a catalyst for a new form of science fiction, one that becomes a strange realism, re-conceptualised as a socially-engaged practice concerned with affective intensity and multiplicity. Parallel to LeGuin, Nichols also reflects on the tensions between “the liberating potential of the cybernetic imagination and the ideological tendency to preserve the existing form of social relations” (627). Nichols argues that there are inherent contradictions embedded within software systems, emerging from the dual ontology of software as both a mode of control and a force that enables collective utterance and deterritorialization; he writes of cybernetic systems: | |||

<blockquote>If there is liberating potential in this, it clearly is not in seeing ourselves as cogs in a machine or elements of a vast simulation, but rather in seeing ourselves as part of a larger whole that is self-regulating and capable of long-term survival. At present this larger whole remains dominated by arts that achieve hegemony. But the very apperception of the cybernetic connection, where system governs parts, where the social collectivity of mind governs the autonomous ego of individualism, may also provide the adaptive concepts needed to decenter control and overturn hierarchy. (640) | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Both LeGuin and Nicholson's perspectives propose a seizing of the means of computation against today’s structures of control - this line of thinking is closely aligned with Deleuze and Guattari's theorising of a “minor literature” (16) - firstly outlined in relation to literature in their book ''Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature'', their understanding of 'the minor' is presented through an analysis of Kafka's literary practice. It is important to note here that the idea of the minor is not utilised by Deleuze and Guattari to denote something small in size or insignificant, but rather the minor operates in a politically-charged sense, where it refers to an alternative to the majority: "a minor literature is not the literature of a minor language but the literature a minority makes in a major language" (Deleuze et. al, 16) - as such, the minor becomes a sort of counter-scale emerging within the overarching political, social, economical and technological scales dominating society. | |||

Deleuze and Guattari further trace the contours of three characteristics of minor literature: the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective assemblage of enunciation. They identify these three conditions as being met in both the content and the form of Kafka's work: Kafka was himself being part of minority within the context of World War II Germany (through his Czech ethnicity and Jewish belief) and therefore was using the majority language of control (German) to produce literature that gave a voice to the marginalised perspectives of those pushed at the fringes of society. Kafka’s work, therefore, becomes an example of how a minority can de-territorialise a mode of expression and use it to affirm perspectives that do not belong to the overall culture that they are inhabiting. The form of Kafka’s work was also minor in structure, which Deleuze and Guattari identified to be networked, claiming that it was akin to "a rhizome, a burrow" (Deleuze et. al, 1) – the quality of being minor, therefore, does not only involve using master frameworks to express alternative views, but can also include exploring other formats of engagement that are distributed and non-linear. Furthermore, Deleuze and Guattari also highlight the transformative power of a minor literature by way of affective resonance specifically, identifying affect as a core element within minor practices. | |||

Perhaps the best way to analyse the concept of the minor as it emerges today is to situate it within the context of resistant technologies. I ask, therefore: what could be a minor tech? | |||

The concept of a minor literature suggests that a re-purposing of a majority language into a minor one can be a powerful method for subversion and resistance against dominant structures of power. Minor literature emerges within marginalised communities that hold other beliefs to those of the major culture that they live in, offering alternative narratives through the deterritorialization of major languages into collective modes of expression that challenge dominant discourses. | |||

A minor tech, then, would be a technology that is deterritorialised – destabilised from its original position and moved into a new territory of possibility; because minor tech exists within a far narrower space than majority tech, everything within it becomes political; and finally, it presents collective value – the latter, to Deleuze and Guattari, is not necessarily ascribed to the collaboration of several individuals for the production of minor language, but rather to the collective value that minority artwork holds; they further highlight the fact that, conceptually, there are insufficient conditions for an individual utterance to be produced in the context of the minor (whilst Big Tech has increased ability to cultivate talent, individualism and mastery, as well the access to high-end tools, minor tech follows a model that doesn't adhere to the existing patterns of the major and often involves DIY, hacking, self-taught methods and collective sharing of knowledge). Minor tech, therefore, becomes cumulative through this sense of the collectivity forming at the core of its production, which generates active solidarities across communities, practitioners and artefacts - a solidarity that cements itself as a collective utterance. | |||

Similarly, the turn towards rendering minor worlds is enabled by the recent deployment of game engine technologies towards critical digital experimentation, enabling artists to produce increasingly complex digital artefacts. Whilst game engine themselves are readily accessible, the majority practices that we can identify have an industrialised, large-scale approach to utilising these, which involves multiple teams working across the production of software in a distributed way, oftentimes split between programmers, who create a game’s system, and designers, who produce assets –this approach is perhaps best seen in AAA productions, which become “collaborative enterprises” (Freedman). Game engines can therefore be considered a majority technology, deeply intertwined with industrialised production methods geared towards economic value and the production of specific, major models of play. Other, more modest, minor ways of engaging with game engines have emerged as a consequence, ones where, most notably, the organisational split between system and asset (or visuality) disappears –attempts at producing minor games are most notably identifiable within indie development communities, however, we can also note the recent emergence of a minor practice concerned with seizing the means of rendering for the purposes of critically exploring more-than-human worlds. | |||

Consequently, we see the emergence of collective efforts to utilise game engines critically within a context of techno-artistic practice, where the technology becomes minor through its harnessing towards the production of minor worlds, where the entertainment-focused properties of commodified games are replaced with experimental assemblages and their affect constellations. Attentive to the properties of a minor language formulated by Deleuze and Guattari, today’s turn towards the production of virtual worlds as sites of alternative possibilities is reterritorializing the existing entertainment-centric and economically-driven mode of existence of immersive game productions. Within the parameters of the game engine itself, the various features, interfaces and functionalities of mainstream game design software, which are geared towards competitive ludic productions, become subverted or dislodged from their privileged status. | |||

When the majority language of the game engine is deployed into the minor territories of experiment and social critique, the connection of the audience with political immediacy is facilitated through the experimental readings that are enabled via computational speculation. As Haraway reminds us, dissent needs “other stories of solace, inspiration and effectiveness” (2016, 49). Pushing beyond the transformation of given content into the appropriate forms expected of major games, these worlds take shape within the territory of the minor, where experimental and non-linear formats that operate in networked and multifaceted ways become materialized. Following in this line of thought, a minor world aims to disrupt established norms and open up new possibilities for social and political transformation - Deleuze positions the minor relationally, claiming that it has "to do with a model – the major – that it refuses, departs from or, more simply, cannot live up to" (Burrows and O’Sullivan, 19). | |||

The emergence of minor worlds, therefore, poses relevant questions about the ways in which collaborating with machines gives rise to practices of techno-artistic resistance that seek decolonial, anti-capitalist and care-driven ways of being. When applied to practices of worlding, the concept of the minor highlights the collective agency of artists in constructing alternative worlds that challenge dominant narratives and ideologies - minor worlds represent a rupturing with the ordinary regime of the present through their undoing and reassembling of the operative logic of reality. Their use of algorithmic processes and tools such as game engine technologies or machine intelligence can result in radically different modes of existence from those dictated by the cultural narratives of capitalism. As Deleuze and Guattari infer, minor practices provide “the means for another consciousness and another sensibility” (17). | |||

One example of envisioning another sensibility through a refiguration of more-than-human relationships can be found in Sahej Rahal’s work ''Antraal'', which explores what it would mean to live as the final humans, now turned into a-historical machines that roam the Earth. In this work, a virtual biome shows strange-limbed non-human actors roaming a video game simulation, operated by artificially intelligent algorithms that act counterintuitively to one another. Marred by the paradoxes scripted in their code, these beings exhibit chaotic behaviours as their machine intelligences struggle, their ontologies lying far outside human-centred thought capabilities - we can see or hear what they are, but we can only assume what they might be. As Negarestani observes, these last humans ‘have refused and subverted the totality of their contingent appearance and significance of their historical manifestations as mere misconceptions of what it means to wander in time, as an idea and not merely a species’ (24), existing in a state that refuses the current epistemological framework of humanity. Rahal's use of video game engines and artifical intelligence allows for thought to be casted speculatively, into a future where existence is dislodged from today's temporal and ontological frameworks and re-established according to different parameters. | |||

[[File:Antraal Gameworld View.jpg|thumb|400px|Figure 4: Sahej Rahal, ''Antraal'', Still from immersive gameworld, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.]] | |||

Another experiment in exploring more-human alliances take shape in the work of Jenna Sutela, via the project ''nimiia cétiï,'' which envisions a language existing outside the master parameters of human expression by deploying intelligent algorithms in the role of a medium that co-interprets data from the Bacilus subtilis bacteria, said to be able to survive on Mars, with recordings of Martian language received from the spirit realm by the by the French medium Hélène Smith. Zhang points out that “Sutela channels the language of the Other to muddy the waters of human sapience, reminding us in synthetic, spiritual and alien tongues that we hold a monopoly over neither intelligence nor consciousness” (154) - ''nimiia cétiï'' is, in essence, a minor language that is at once an exploration in seeking other modes of expression and a vestige to the possibilities that lay beyond the frameworks of language cultivated throughout human history. | |||

Both previous examples stand as visions projected from outside our Anthropocentric moment – they refuse the current narratives and knowledge systems of capitalism and attempt to use intelligent technologies or game engines to explore what a more-than-human assemblage could look, sound or ultimately feel like. In this convergence of artistic practice, software and politics, worlding through algorithms offers a pathway towards ways of being and knowing otherwise, through a re-purposing of the majority of computational and algorithmic tools surrounding us today into a minor language, able to render affective world instances. As Kelly observes, these artists ‘embrace technological development in their lives and work, but in a manner that is cognisant and critical of the frameworks that have developed within the tech industry’s supposed focus on human-centred advancement, which is inevitably driven by the demands of capital’ (4). Worlding, therefore, becomes a political act that aligns with the principles of minor literature in terms of its transformative potential. It invites us to challenge dominant modes of representation, question established boundaries, and imagine new possibilities. By constructing alternative worlds, these artists aim to challenge dominant narratives, ideologies of power, and structures of control and prompt audiences to envision different social, cultural, and political realities. | |||

== Conclusion == | |||

To conclude, we can begin to acknowledge that practices of worlding emerge as dynamic forces concerned with reshaping our understanding of technological, cultural and political structures. By harnessing the power of the majority tech operating in society, artists engage in a process of world-making that transcends traditional boundaries and opens up new possibilities for creative expression and political resistance. Drawing on the concept of a minor literature put forth by Deleuze and Guattari, we can situate worlding as a politically charged act of subversion and empowerment, by understanding it as minor practice in relation to the majority (or master) structures and narratives that perpetuate inequality, injustice, and oppression. Moreover, the harnessing of algorithmic technologies for speculatively rendering worlds can provide a fertile ground to explore modes of being otherwise, through the creation of immersive and interactive experiences of a different lifeworld, thus enabling artists to engage audiences in critical reflections on power dynamics, social hierarchies and more-than-human alliances. | |||

Worlding disrupts the established order of things by refusing dominant narratives and offering counter-hegemonic visions of the world - it gives voice to other, more-than-human perspectives and challenges oppressive power structures - as Kathleen Stewart puts it, worlding allows for “an attunement to a singular world’s texture and shine” (340), an ability to not only envision , but relationally tune into a space of possibility, to hold open a portal into another cosmology. In this way, worlding becomes a form of resistance, enabling the creation of alternative realities and fostering the potential for social transformation through inviting audiences to critically engage with new possibilities for social or ecological change. | |||

So, I close with a question, which sets up my research agenda: how can we situate and conceptualise these acts of worlding through an understanding of their relationship with software and affect, and how can the resulting networked epistemologies shape a politics of worlding in tune with what Zylinska defines as a minimal ethics for the Anthropocene? | |||

== Works cited == | |||

<div class="workscited"> | |||

Anable, A. “Platform Studies.” ''Feminist Media Histories'', vol. 4, issue no. 2, 2018, pp. 135-140. | |||

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Geoff Cox. "Toward a Minor Tech". ''A Peer-Reviewed Newspaper'', edited by Christian Andersen and Geoff Cox, vol. 12, no. 1, Apr. 2023, p. 1. | |||

Bellacasa, María Puig de la. ''Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds''. University of Minnesota Press, 2017. | |||

Braidotti, Rosi. ''Posthuman Knowledge''. Polity Press, 2019. | |||

Burrows, David, and Simon O’Sullivan. ''Fictioning: The Myth-Functions of Contemporary Art and Philosophy''. Edinburgh University Press, 2019. | |||

Cadena, Marisol de la, and Mario Blaser, editors. ''A World of Many Worlds''. Duke University Press, 2018. | |||

Cheng, Ian. ''BOB: Bag of Beliefs''. Simulated lifeform, 2018-2019. | |||

'' | |||

Cheng Ian. ''BOB Shrine''. Software Application, Version 1.7, Metis Suns, 2019. | |||

Cheng, Ian, et al. ''Ian Cheng: Emissary’s Guide to Worlding''. 1st ed., Koenig Books and Serpentine Galleries, 2018. | |||

Cheng, Ian. ‘Worlding Raga: 2 – What Is a World?’ ''Ribbonfarm'', 5 Mar. 2019, https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2019/03/05/worlding-raga-2-what-is-a-world/. | |||

Chun, W.H.K. (2004). “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge.” ''Grey Room'', no 18, Winter 2004, pp. 26-51. | |||

Deleuze, Gilles, et al. "What Is a Minor Literature?". ''Mississippi Review'', vol. 11, no. 3, 1983, pp. 13–33. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20133921. | |||

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. ''Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature''. First Edition, vol. 30, University of Minnesota Press, 1986. | |||

Fisher, Mark. ''Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?''. Zero Books, 2012. | |||

Foucault, Michel. ''The History of Sexuality''. Volume I, Vintage Books, 1978. | |||

Foxman, Maxwell. "United We Stand: Platforms, Tools and Innovation With the Unity Game Engine". ''Social Media + Society'', vol. 5, no. 4, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119880177. | |||

Freedman, Eric. "Engineering Queerness in the Game Development Pipeline". ''Game Studies'', vol. 18, no. 3, Dec. 2018, https://gamestudies.org/1803/articles/ericfreedman. | |||

Gibson, William. ''Pattern Recognition''. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2003. https://archive.org/details/patternrecogniti00gibs/. | |||

Gregg, Melissa and Seigworth, Gregory J. ''The Affect Theory Reader''. Duke University Press, 2010., https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822393047. | |||

Haraway, Donna J. "SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far". ''Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology'', no. 3: Feminist Science Fiction, November 2013. DOI:10.7264/N3KH0K81 | |||

Haraway, Donna. ''Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene''. Duke University Press, 2016. | |||

Keiken. ''BET(A) BODIES''. Haptic wearable womb, 2021. | |||

Kelly, Miriam. “Feedback Loops”. ''Feedback Loops'', ACCA Melbourne, 2020, pp. 22-26. | |||

LeGuin, Ursula K. “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”. ''Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places'', Ursula K. LeGuin, Grove Press, 1989. pp. 165 – 171. | |||

Marino, Paul. ''The Art of Machinima: Creating Animated Films with 3D Game Technology''. 1st edition, Paraglyph Press, 2009. | |||

Massumi, Brian. “Deleuze, Guattari, and the Philosophy of Expression”. ''Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/ Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée''. Sept. 1997, pp. 751–783. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/crcl/index.php/crcl/article/view/3739. | |||

McPherson, Tara. ''‘U.S. Operating Systems at Mid-Century: The Intertwining of Race and UNIX’''. Race After the Internet, Routledge, 2011. | |||

Munster, Anna. ''An Aesthesia of Networks: Conjunctive Experience in Art and Technology.'' MIT Press, 2013, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8982.001.0001. | |||

Murray, Janet. "Did It Make You Cry? Creating Dramatic Agency in Immersive Environments". ''Virtual Storytelling. Using Virtual Reality Technologies for Storytelling'', edited by Gérard Subsol, Springer, 2005, pp. 83–94. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1007/11590361_10. | |||

Murray, Janet. “Glossary”. ''Humanistic Design for an Emerging Medium''. 20 May 2023. https://inventingthemedium.com/glossary/. | |||

Negarestani, Reza. “Sahej Rahal: A Life That Wanders in Time”. ''Feedback Loops''. ACCA Melbourne, 2020, pp. 22-26. | |||

Nichols, Bill. “The Work of Culture in the Age of Cybernetic Systems”. ''Screen'', Volume 29, Issue 1, Winter 1988, Pages 22–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/29.1.22. | |||

Palmer, Helen and Hunter, Vicky. “Worlding”. ''New Materialism: How Matter Comes to Matter'', 2018, https://newmaterialism.eu/. | |||

Rahal, Sahej. ''Antraal''. Simulated biome, 2019. | |||

Stengers, Isabelle. ''In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism''. Open Humanites Press, 2015. http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/in-catastrophic-times/. | |||

Stewart, Kathleen. "Afterword: Worlding Refrains". ''The Affect Theory Reader'', Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 339–54. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822393047-017. | |||

Sutela, Jena, Akten, Memo and Henry, Damien. ''nimiia cétiï''. Speculative audio-visual work, 2018. | |||

Zhang, Gary Zhexi. “Jenna Sutela: Soult Meat and Pattern”. ''Magic'', edited by Jamie Sutcliffe, Co-Published by Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press, 2021, pp. 153-156. | |||

Zylinska, Joanna. ''Minimal Ethics for the Anthropocene.'' Open Humanites Press, 2014. pp. 20. | |||

</div> | |||

[[Category:Toward a Minor Tech]] | |||

[[Category:5000 words]] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:29, 13 September 2023

Teodora Sinziana Fartan

Rendering Post-Anthropocentric Visions:

Worlding As a Practice of Resistance

Rendering Post-Anthropocentric Visions: Worlding As a Practice of Resistance

Abstract

This paper formulates a strategic activation of speculative-computational practices of worlding by situating them as networked epistemologies of resistance. Through the integration of Deleuze and Guattari's concept of a ‘minor literature’ with the distributed software ontologies of algorithmic worlds, a tentative politics for thinking-with worlds is mapped, anchored in the potential of worlding to counter the dominant narratives of our techno-capitalist cultural imaginary. With particular attention to the ways in which the affordances of software can become operative and offer alternative scales of engagement with modes of being-otherwise, an initial theoretical mapping of how worlding operates as a multi-faceted and critical storytelling practice is formulated.

Introduction

Emanating from the fog of late techno-capitalism, the contours of a critical techno-artistic practice are starting to become visible - networked, immaterial and often volumetric, practices of worlding surface as critical renderings concerned with speculatively envisioning modes of being otherwise through computational means. By intersecting software and storytelling, these practices cultivate more-than-human assemblages that foreground possible world instances - worlding, thus, becomes politically charged as a networked epistemology of resistance, where dissent is enabled through the rendering of alternative knowledge systems and relational entanglements existing beyond the ruins of capitalism.

In the ontological sense, practices of worlding materialise as algorithmic portals into fictional terrains where alternative modes of being and knowing are envisioned; they refuse to adopt a totalising view of the megastructure of capitalism’s cultural imaginary and instead opt to zoom in onto the cracks appearing along its edges, where other narrative possibilities are starting to sprout and multiply. Through the evocative affordances of software, practices of worlding teleport us forwards, amidst the ruins of the Anthropocene, where “unexpected convergences” emerge from the debris of what has passed (Tsing 205).

In their quests for speculative possibility, world-makers are dislodging existing hi-tech systems and platforms from their conventional economical or institutional roles and repurposing them as technologies of possibility which seek to de-centre the dominant narratives of the Western cultural imagination. A reversing of scales therefore occurs, where 'high tech' becomes deterritorialized and mobilised towards the objectives of a 'minor tech', which seeks to counter the universal ideals embedded in technologies through foregrounding "collective value" (Cox and Andersen 1).

Consequently, recent years have seen an increased interest in the (mis)use of software such as game engines or machine learning for the artistic exploration of crossovers between the technological, the ecological and the mythical; specifically, through the emergence of increasingly capable and accessible platforms such as Unreal Engine and Unity, game engines have become the creative frameworks of choice for conjuring worlds due to their potential for rapid prototyping and increased capacity of rendering complex, real-time virtual imaginaries. Whilst worlding can exist across a spectrum of algorithmically-driven techniques and systems, it is most often encountered through (or integrates within its technological assemblage) the game engine, as we will see in the course of this paper.

In what follows, I aim to at once activate an initial cartography of ‘worlding’ as an emergent techno-artistic praxis and propose a tentative politics for thinking not only through, but also with worlding as a process that can facilitate ways of imagining outside the rigid narratives of techno-scientific capitalism.

I propose that it is particularly through its refiguring of computational methodologies that worlding positions itself as an exercise in creative resistance. Through a refiguration of technology as a speculative tool, worlding offers a potent method for thinking outside of our fraught present by algorithmically envisioning radically different ontologies - these modes of being-otherwise, I contend, also bring forth a new epistemological and aesthetic framework rooted in both the affordances of the technological platforms used for their production and the relational assemblages at their core: the network, in itself, becomes unearthed throughout this paper as the essence of algorithmic world instances and is proposed as a mode of conceptualisation for these practices.

Within the context of political resistance, by approaching these algorithmically-rendered worlds through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of a 'minor literature' (16), we can trace the emergence of minor worlds as potent and powerful assemblages for countering the majority worlds of platform capitalism and their dominant socio-cultural narratives - what can these minor worlds reveal about more-than-human collaborations and the critical role of software within speculative practices? How do they become operative as instruments for de-centering the master narratives of our present? What alternative knowledges do they draw upon within their ontologies and what potentialities do they open up for encountering these?

Throughout this paper, the worlds conjured by artists such as Ian Cheng, Sahej Rahal, Keiken and Jenna Sutela will be drawn on in order to gain insight into the ways in which worlding at once becomes operative as a form of social and political critique and activates a process of collective engagement with potent acts of futuring, where a co-existence together and alongside the non-human is foregrounded.

Worlding in the age of the anthropocene

Today, there seems to be a widespread view that we are living at the end - of liberalism, of imagination, of time, of civilisation, of Earth; engulfed in the throes of late capitalism, conjuring a possible alternative seems exceptionally out of grasp. In his novel Pattern Recognition, which constitutes a reflection on the human desire to detect patterns and meaning within data, William Gibson formulates a statement that rings particularly relevant when superimposed onto our present state:

we have no idea, now, of who or what the inhabitants of our future might be. In that sense, we have no future. Not in the sense that our grandparents had a future, or thought they did. Fully imagined cultural futures were the luxury of another day, one in which 'now' was of some greater duration. For us, of course, things can change so abruptly, so violently, so profoundly, that futures like our grandparents' have insufficient 'now' to stand on. We have no future because our present is too volatile […] We have only risk management. The spinning of the given moment's scenarios. Pattern recognition. (57)

Here, Gibson makes reference to the near-impossibility of imagining a clear-cut future in a present that is marred by ecological, political and social unrest - I contend that this fictional excerpt is distinctly illustrative of the affective perception of life within the age of the anthropocene, where the volatility of the present, caused by the knowledge that changes on a planetary scale are imminent, ensures that a given future can no longer be predicted or visualised. Without the ability to rationally deduce a logical outcome, what we, too, are left with is a sort of pattern recognition - an attempt to find patterns for ways of being and knowing that can become the scaffold for visions of the future; as Gibson foregrounds, today, rather than being logically deducible, the future needs to be sought through the uncovering of new patterns.

Just like Gibson's character, we do not know what kind of more-than-human assemblages will inhabit our future states - and it is precisely here that this act of pattern recognition intersects with the core agenda of worlding: how can we envision patterns of possible futures using computation? Within our own contemporary context, where asymmetrical power structures, surveillance capitalism and the threat of climate change deeply complicate our ability to think of possible outcomes, where can new patterns emerge?

In the wake of the Anthropocene, feminist critical theory has launched several calls for seeking such patterns with potential to provide a foothold for experiments in imagining future alternatives: from Stenger’s bid to cultivate “connections with new powers of acting, feeling, imagining and thinking” (24), to Haraway’s request for critical attention to “what worlds world worlds” ("Staying with the trouble" 35) and LeGuin’s plea for a search for the ‘other story’ (6) - an alternative to the linear, destructive and suffocating narratives regurgitated perpetually within the history of human culture. We can, therefore, trace the emergence of a collective utterance, an incantation resonating across feminist epistemologies, emphasising the urgency of developing patterns for thinking and being otherwise - as Rosi Braidotti asks, “how can we work towards socially sustainable horizons of hope, through creative resistance?” (156)

In a reality marred by a crisis of imagination, where “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than that of capitalism” (Fisher 1), casting one’s imagination into a future that refuses the master narratives of capitalism is no easy feat, and requires, as Palmer puts it, a "cessation of habitual temporalities and modes of being" ("Worlding") in order to open up spaces of potentiality for speculative thinking - to think outside ourselves, towards possible future alternatives, has therefore become a difficult exercise within the current socio-political context.

We can then identify the most crucial question for the agenda of worlding: what comes after the end of our world (understood here as capitalist realism (Fisher 1))? Or, better phrased, what can exist outside the scaffolding of reality as we know it, dominated by asymmetric power structures, infused with injustice, surveilled by ubiquitous algorithms and continuously subjected to extractive practices? And what kind of technics and formats do we need to visualise these modes of being otherwise?

Techno-artistic worlding practices attempt to intervene precisely at this point and open up new ways of envisioning through their computational nature - which, in turn, produces new formats of relational and affective experience through the generative and procedural affordances of software. The world-experiments that emerge from these algorithmic processes constitute hybrid assemblages of simulated spaces, fictive narratives, imagined entities and networked entanglements - collectively, they speculatively engage with the uneven landscape of being-otherwise, its multiplicities and many textures and viscosities.

Listening to the operational logic of computationally-mediated worlds

To begin an analysis of how worlding attempts to engage with the envisioning of alternatives, we'll first turn to Donna Haraway, who further instrumentalizes the idea of patterning introduced earlier through Gibson: when situating worlding as an active ontological process, she says that "the world is a verb, or at least a gerund; worlding is the dynamics of intra-action [...] and intra-patience, the giving and receiving of patterning, all the way down, with consequences for who lives and who dies and how" ("SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far" 8). By making the transition from noun to verb, from object to action, worlds and patterns become active processes of worlding and patterning. In Haraway's theorising of speculative fabulation, patterning involves an experimental processes of searching for possible "organic, polyglot, polymorphic wiring diagrams" - for a possible fiction, whilst worlding encapsulates the act of conjuring a world on the basis of that pattern ("SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far" 2). Furthermore, Haraway situates worlding as a practice of collective relationality, of intra-activity between world-makers and world-dwellers, as well as between world and observer, through a networked process of exchange. It is important to note that worlding, to Haraway, is far from apolitical: she evidences its relevance by defining it as a practice of life and death, which has the potential to engage in powerful formulations of alternatives - acts which might be crucial in establishing actual future states. As she argues, “revolt needs other forms of action and other stories of solace, inspiration and effectiveness” ("Staying with the Trouble" 49)

To gravitate towards an understanding of these other stories, we'll approach worlding in context through the eyes of Ian Cheng, an artist working with live simulations that explore more-than-human intelligent assemblages. Cheng defines the world, as “a reality you can believe in: one that promises to bring about habitable structure from the potential of chaos, and aim toward a future transformative enough to metabolise the pain and pleasure of its dysfunction” ("Worlding Raga") - a world, in this perspective, needs to be an iteration of the possible, one that presents sufficient transformative power for existing otherwise; the referencing of 'belief' is also crucial here as, within capitalist realism, where all "beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration" (Fisher 8), its very activation becomes and act of revolt.

Of worlding, Cheng says that it is “the art of devising a World: by choosing its dysfunctional present, maintaining its habitable past, aiming at its transformative future, and ultimately, letting it outlive your authorial control” ("Worlding Raga") - the world-maker, therefore, does not only ideologically envision a possible reality, but also renders it into existence through temporal and generative programming. Cheng balances this definition within the context of his own practice concerned with emergent simulations, where authorship becomes a distributed territory between the human and more-than-human.

It is important to note that Cheng refuses to ascribe any particular form, medium or technology as an ideal template of worlding - rather, discreetly and implicitly, Cheng’s definition evokes the operational logic of algorithms by referencing the properties of intelligent and generative software systems. The definiton's refusal of medium-specificity mirrors the multiplicity of ways in which algorithms can world: whilst many of these worlds initially unfold as immersive game spaces (and then become machinima, or animated films created within a virtual 3D environment (Marino 1) when presented in a gallery environment), satellite artefacts can emerge from a world's algorithmic means of production, often becoming a physical manifestation of that world's entities - taking shape, for example, as physical renditions of born-digital entities, as seen in the sculptural works as that emerge from Sahej Rahal's world, Antraal, where figures of the last humans, existing in a post-species, post-history state, are recreated outside of the gamespace.

Transgressions of the fictional world into real-space can take a variety of shapes, depending on the politics and intentions of that world: other examples of worlds spilling out of rendered space and into reality are Keiken's Bet(a) Bodies installation, where a haptic womb is proposed as an emphatic technology for connecting with a more-than-human assemblage of animal voices and Ian Cheng’s BOB Shrine App that accompanied his simulation BOB (Bag of Beliefs) in its latter stages of development, through which the audience can directly interact with the AI by sending in app 'offerings', which impress what Cheng terms 'parental influence' on BOB, in order to offset its biases.

Consequently, it becomes apparent that practices of worlding are governed by an inherent pluralism - due to this multiplicity of possible tools and algorithms that can operate within the scales of worlding, we are in need of an open-ended definition that can encapsulate commonalities whilst also allowing for plurality of form - I propose here to focus on the unit operations making these worlds possible. From gamespace environments to haptic-sonic assemblages or interactive AI, the common denominator of all these artefacts does not lie in their media specificity, but rather in their software ontology and its procedural affordance, defined by Murray as "the processing power of the computer that allows us to specify conditional, executable instructions" ("Glossary").

A working definition for worlding that integrates unit operations with speculative logic can be therefore traced: worlding is a sense-making exercise concerned with metabolising the chaos of possibility into new forms of order through the relational structures enabled by procedural affordances. It involves looking for the logic that threads a world together and then scripting that logic into networked algorithms that render it into being. To world with algorithms is to dissent from the master narratives of capitalism by critically rendering habitable alternatives.

Crucial to this definition is an understanding of software as a cultural tool - its procedural affordances, as Murray reflects, have "created a new representational strategy, [...] the simulation of real and hypothetical worlds as complex systems of parameterised objects and behaviours" ("Glossary"). To understand the operative logic that enables procedural worlds, a similar pluriversal analytical model to that proposed by de la Cadena and Blaser (4) becomes necessary for conceiving these ecologies of practice - I propose, therefore, a conceptual model for understanding the symbolic centre of worlding by turning to the ways in which software itself creates and communicates knowledge: the network.

Reflecting on Tara McPherson's assertion that “computers are themselves encoders of culture” (36), being able to produce not only representations but also epistemologies, one must wonder, then: in the context of of algorithmic worlds, how do their networked cores become culturally charged? What kind of new knowledges become encoded in their procedural affordances?

Thinking with networks: an epistemic shift towards relationality

Another vector through which the nature of worlding can be theoretically approached emerges from Anna Munster’s theorising of networks, particularly her definition of ‘network anaesthesia’ - a term she develops to suggest the numbing of our perception towards networks, making their unevenness and relationality obscure (3). A similar anaesthesia can be identified when working with platformised tools such as game engines, where, as Freedman points out, "the otherwise latent potential of code, found in its modularity, is readily sealed over" - due to code becoming concretized into objects, the computational inner workings of certain aspects become blackboxed (Anable, 137). The trouble with engines is that, in our case, they promote a worlding anaesthesia, where the web of relations at play within that world instance is not immediately apparent due to their obscuring of software.

Wendy Chun speaks of a similar paradox to that of the network anaesthesia by referencing the ways in which computation complicates both visuality and transparency. Visuality in the sense of the proliferation of code objects that it enables, and transparency in the sense of the effort of software operations to conceal their input/output relationalities - visualising the network, therefore, becomes an exercises in revealing the inner workings of worlds, one that resists the intentional opacity of the platforms that become involved in their genesis.

Munster, too, calls for more heightened reflective and analytical engagements with “the patchiness of the network field” (2) by making its relations visible (and implicitly knowable) through diagrammatic processes. She contends that, in order to decode the networked artefact, we must attempt to understand the forces at play within it from a relational standpoint:

We need to immerse ourselves in the particularities of network forces and the ways in which these give rise to the form and deformation of conjunctions — the closures and openings of relations to one another. It is at this level of imperceptible flux — of things unforming and reforming relationally — that we discover the real experience of networks. This relationality is unbelievably complex, and we at least glimpse complexity in the topological network visualisation. (3)

For Munster, therefore, the structuring of relations and their interconnectedness is paramount to any attempt at making sense of the essence of a software artefact or system. This relational perspective towards networked assemblages opens up a potent line of flight for the conceptualisation of the processes involved in the rendering of worlds - if the centre of a world is a network, that can in itself sustain a number of inputs and outputs of varying degrees of complexity, interlinked in a constant state of flux, then any attempt to understand such a world must involve conceptual engagement with the essence of the network, or the processes through which relations open and close and produce these states of flux. Engagement with algorithmic worlds, therefore, moves from the perceptual into the diagrammatic, from a practice of observation to one of sense-making, involving not only visualisations but also a certain computational knowing, an understanding of relations and flows. I argue here that engagement with worlds necessitates an increased type of cognitive engagement, one that allows us to understand the object of discussion differently, through a foregrounding of relational exchanges.

I propose a turn towards cartographing the relations that operate within a world on an affective level, due to the spaces of evocative possibility opened up by a world's procedural affordances. Murray draws on EA's 1986 advert asking "Can a computer make you cry?" to reflect on the need for increased critical attention to be given to the ways in which affective relations form within a procedural space; she argues that "tears are an appropriate measure of involvement because they are physiological and suggest authenticity and depth of feeling" (84), but clarifies that it is precisely the visceral aspect of crying that is of interest - the focus is not on "sad content, but compellingly powerful and meaningful representation of human experience" (85). She observes that, in the domain of video games, whilst there are some experiments with instilling emotion in viewers, these are not yet complex structures of feeling; she calls, therefore, for the development of computational experiences that constitute "compellingly powerful and meaningful representation of human experience", highlighting the crucial importance of affect. By further extending this idea into the territory of worlding, it becomes apparent that structures of feeling are essential for creating worlds that engage in resistance, and identify Murray's call as a core element on the agenda of worlding.

Today, we are already seeing experiments in ‘knowing’ networks emerging - we'll circle back to Cheng here, who seems to have stablished a practice of conceptually diagramming his work on BOB (Bag of Beliefs) - one that does not simply relate input to output or technically map, but also pays attention to producing a cartography of the affective relations scripted into BOB's world. By showing increased tendencies towards engagement with not only the network itself, but also the networking, Cheng traverses the crucial space between the perceived (the immediate) and the perceptual (the more esoteric, affectively charged circulations of data within a system), as seen in the examples of Figures 2 and 3, which do not seek to formally capture the elements of a network assemblage, but rather, to create a “topological surface” (Massumi 751) for the experience of that world.

As Munster inflects, the goal is “not to abstract a set of ideal spatial relations between elements but to follow visually the contingent deformations and involutions of world events as they arise through conjunctive processes” (5) - in Cheng’s diagram, we see a phenomenological and epistemological topology of the networking processes at play, where affective relations are beginning to be mapped alongside algorithmic diagramming - in the spaces between memory, narrative and desire, a spectrum of relational flows and possibilities emerge. Demonstrating the essence of the network through its flow of relations, Cheng attempts to diagram the simulation across both affective and technical scales.

Thinking with (rather than simply through) worlding, can, therefore, produce an affective networked epistemology where an increased attention to relationality can cultivate new ways of both seeing and understanding beyond the purely machinic. A question of scale emerges here: how do affective and technological scales become intertwined within computer-mediated worlds? When thinking-with worlds, care needs to be taken to address the affective scale along the technical one - how do these scales have the potential to affect one another and the much larger scale of human experience? This vector of research constitutes a significantly larger line of enquiry, one that I will delegate to worlding's future research agenda - for now, I'll return to Murray's note on computers and tears and ask: could worlds make us cry?

Rendering resistance: the emergence of minor worlds

In an age of anxiety underscored by invasive politics and ubiquitous algorithmic megastructures, the major technologies of the present such as artificial intelligence, game engines, volumetric rendering software and networked systems are employed in the service of extractive and opaque practices. However, as Foucault proclaims, “where there is power, there is resistance” (95): when dislodged from their socio-economical frameworks and taken amidst the ruins of the same reality, crumbling under the weight of late techno-capitalism, these technologies can also become an instrument of dissent - to simulate a world volumetrically, epistemologically and relationally becomes an exercise in (counter)utilising the major technologies of the present in order to produce tactics that lead out of these ruins and into a future dominated by new, pluralistic, decentralised and distributed agencies taking shape according to “ecological matters of care” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 24).

To resist, here, means to engage with the broader questions of power and refusal within the context of software practices. Within practices of worlding, this refusal of capitalism’s master narratives in favour of imagining otherwise takes shape through a more-than-human entanglement with technologies that are capable of procedurally rendering a glimpse into alternative modes of being through simulation. As LeGuin proposes, technology can be dislodged from the logic of capitalism and refigured as a cultural carrier bag (8); in this sense, she envisions this refiguration as a catalyst for a new form of science fiction, one that becomes a strange realism, re-conceptualised as a socially-engaged practice concerned with affective intensity and multiplicity. Parallel to LeGuin, Nichols also reflects on the tensions between “the liberating potential of the cybernetic imagination and the ideological tendency to preserve the existing form of social relations” (627). Nichols argues that there are inherent contradictions embedded within software systems, emerging from the dual ontology of software as both a mode of control and a force that enables collective utterance and deterritorialization; he writes of cybernetic systems: