Toward a Minor Tech:Niederberger5000

Calling the User. Interpellation and Narration of User Subjectivity in Mastodon and Trans*Feminist Servers

Abstract

In recent years, a large body of work has analyzed the cultural and social ramifications of data-driven digital environments that currently structure digital practice. However, the position of the user has scarcely been developed in this field.

In this paper I discuss how user subject positions are invoked by digital infrastructures as an alternative to big technology platforms. With subject positions I mean a shared and often unarticulated understanding of what kind of technological practice is meant when we talk about users: user as a cultural form. I start with the analysis of a crisis in user subjectivity as it manifested in the migratory waves from Twitter to Mastodon at the end of 2022, after Elon Musk bought Twitter. Like Twitter, Mastodon is a microblogging service, but it operates as a network of connected servers run by nonprofit organizations and communities. I argue that Mastodon—by way of its infrastructural organization around servers and communities—invokes a different subject position of the user than the self-contained autonomous liberal subject, one that is based on a relationship with a community. In a second case study, I discuss how the artistic activist practices of Trans*Feminist Servers create a territory to rethink relations to technology itself, most prominently through raising questions of servitude: what does it mean to serve and to be served? I argue that through this, Trans*Feminist Servers are able to reformulate use as part of relations of care and maintenance and implement them in their technological practice. As I conclude, both Mastodon and Trans*Feminist Servers project a user exceeding the neoliberal subject. While Mastodon does so by proposing a subject position related to a community first, Trans*feminist Servers go a step further and moreover open use as a practice beyond consumption, thus operate on relations to infrastructure itself.

Keywords:

subjectivity, data, infrastructure, practice, Feminist Servers, Trans*Feminist Servers, platforms, social media, Twitter, Mastodon, feminism, relational technology

Introduction

People are constantly involved in a process of becoming a user through technology. Today, technology usually means data-driven environments that permeate everyday life, from the personal to the professional sphere, and shape the ways we relate to each other, to ourselves, and to the world as well as how we organize on a social and political level. Data is everywhere, and large amounts of data are produced by users through interactions with platforms and cloud-based digital infrastructures. What does it mean to be a user today? How does data-driven technology profit not only from user interaction, but also produce the “user”? How can we think through the relations of platforms and users in ways that offer different imaginations, and thus open up a space to act?

This article is interested in the user as a cultural form, a mostly implicit and unarticulated shared understanding of what kind of technological practice is meant when we talk about users. This is not a psychological perspective focused on the inner life of an individual, neither it is an anthropological view of a group of living persons in their specific cultural contexts. The user as a cultural form is concerned with subjectivity, but as shared imaginations. Subjectivity itself is individual, the temporal situation of a person through which individuals makes sense of the world. It is a continuous process of becoming particular in relation to the complexities of the world. But as philosopher Olga Goriunova highlights, subjectivity is always developed in relation to shared imaginations about what it means to be in the world, e.g., as a woman, an adult, or—in our case—a user. These shared cultural imaginations are called “subject positions”(Goriunova, “Uploading Our Libraries”). They are role models or figurations and provide a position in the world from which to make sense. As shared imaginations, subject positions are articulated and developed in the cultural domain. Furthermore, they are also aesthetic positions in the sense that they formulate a position from where practice is possible, as Goriunva insists. Thus subject positions are shaped by practice and the communities around them. Goriunova has exemplified this for very specific practices at the intersection between commons and digital activist/artistic practices (Goriunova, “Uploading Our Libraries”), but the principle of linking practice and subjectivity also applies to the more general field of everyday use.

Despite their central position in data, users are considered only at the margins of the current critical discourses about the implications of data-driven environments. In the field of Critical Data Studies, a substantial body of work emerged about the cultural and political ramifications of data-driven environments (Boyd and Crawford; Iliadis and Russo). It raises important questions about flaws and bias in data (Eubanks), how data-driven systems enhance inequality (O’Neil), extend colonial modes of exploitation and thingification (Couldry and Mejias), and install new forms of discrimination (Benjamin). However, the position of the user remains underdeveloped in this field and is primarily discussed in terms of abuse and exploitation.

But big data is not only a new way of organizing and operationalizing knowledge obtained from users, but constitutes a new mode of signification. As law philosopher Antoinette Rouvroy explains, data produces meaning out of itself, and not about the world. The data about a user’s browsing history does not mean her journey surfing the web, but is taken as an indicator of personality, age, gender, interests, economic situation, and many more, often secret categories. The recorded traces users leave thus take on a life of their own. This is a process of signification that is not indexical. Thus data does not operate through representation or causality, but by probability and statistics. Goriunova suggests the term “distance” to describe this nonindexical relation between people and data (Goriunova, “The Digital Subject”). It is through distance that big data produces new modes of governmentality and as well as new subjects, with far-reaching consequences, e.g., for the legal domain (Rouvroy).

How users make sense of this distance is investigated in another emerging field I call “User Studies.” It is a body of work in anthropology that addresses sense-making processes about algorithms and platforms (Siles et al.; Bucher; Rader, and Gray; Devendorf and Goodman). These studies articulate technology not as essentialist independent artefacts, but as something that is created through shared praxis, as culture (Seaver). They are an important contribution to the understanding of the position users have in the contemporary data-driven digital world. However, through their focus on users as individuals and on bottom-up sense-making processes, they are only marginally concerned with the subjectivity of users, discussing it under the term of identity (Karizat et al.). They often fail to address the political dimensions as articulated in Critical Data Studies and do not consider the cultural forms of subject positions.

Subjectivity is linked not only to technology, but also to the broader sociocultural environment. This has been a recurrent topic in Cultural Studies (Hall). Here, the term “subjectivity” has a meaning similar to “subject positions,” as explained above. Especially in feminist scholarship, there is an ongoing debate about how subjectivity is shaped by neoliberal formations (Banet-Weiser) and how it responds to critical perspectives, incorporating them into new narratives about femininity as self-empowered and independent, however problematic and conflicting they may be (Gill and Kanay). This body of work highlights the role of narratives mobilizing values, which circulate in a culture deeply shaped by capitalist dynamics. However, it is not directly concerned with users and big data technologies, but provides a backdrop of the manifold ways culture and institutions are involved in the creation, maintenance, and transformation of widely shared basic forms of subjectivity that the subject position of the user inherit.

The user as a distinct part of the cultural history of technology is only rarely specifically discussed. Notable examples are Olia Lialina, who mapped conceptualizations of the user in the historical discourse in HCI (human-computer interface) (Lialina), and Joanne McNeil, who traced a cultural history of the Internet from the perspective of users themselves, highlighting the diversity of experiences and cultural differences that manifest in and through technology (McNeil).

The shared imaginations of user subject positions as a specific position in technological practice is deeply political, because it is not only a bottom-up sense-making process as investigated by Users Studies, but claims subjectivity as precisely that place where the power relations in technology, as analyzed in Critical Data Studies, are inscribed in the self-understanding of users, thus reproducing them. As already explained, this analysis takes subjectivity—and in extension subject positions—as a place of being affected, but also as a place of claiming agency. This analysis follows Louis Althusser’s concept of interpellation (Althusser et al.), draws on performative concepts of identity (Butler), and extends a line of thinking that considers how subjectivities are both expressed in and shaped by mass media (Silverman and Atkinson).

In this paper I will bring these strands of thinking together through an analysis of two case studies. The first is an analysis of a contemporary event: the wave of migration from Twitter to Mastodon following the acquisition of the former by Elon Musk. I argue that some of the difficulties of switching to Mastodon can be analyzed as a crisis in the subject position of the user, and I will discuss the role of infrastructural organization in this crisis.

Because subject positions live and are transformed in the cultural field, cultural and artistic practice provide a privileged position of developing methods and practices of doing otherwise. In the second case study I discuss Trans*Feminist Servers as an artistic-activist strategy on the terrain of cultural imagination of technology itself. Trans*Feminist Servers aim at developing other subjectivities and fostering different practices of being a user, both as a conceptual tool and as lived technological practice. This allows reclaiming user practice as a place for careful relationships not only with a community (as in the first case study of Mastodon’s interpellation of user subjectivity), but also with technology itself.

The Twitter Crisis

When Elon Musk bought Twitter at the end of October 2022, people started discussing alternatives. One of them was Mastodon—like Twitter, a micro-blogging service. Unlike Twitter, Mastodon is not corporate-owned. It is a network of connected servers that are often run by small collectives and nonprofit organizations. Following the acquisition of Twitter by Musk and during every wave of policy change that followed, the Mastodon network showed waves of new registrations. During little more than three months, the Mastodon network grew from 4.5 to 9 million users and, more significantly, from 3,700 to 17,000 servers (according to the User Count Bot for all known Mastodon instances @mastodonusercount@mastodon.social). For comparison purposes: Twitter has 368 million users (Iqbal), so even with the steady growth of Mastodon’s user count, changing from Twitter to Mastodon is a movement through technological scale, with many consequences (because platforms thrive on network effects: the more numerous their users, the more valuable the platform is for everybody [Srnicek 45]). But on the part of the users, this was often experienced as a crisis in subjectivity:

Fig. 1: Screenshot of a Twitter post by a friend of mine: “As long as the alternatives (somewhat pointedly formulated) are ‘from nerds for nerds,’ this discussion is of little use. This is just how nerds accuse everyone else of being lazy. I would be more interested in discussing who should be responsible for a more inclusive web (commons, public service).” (author’s highlighting and translation)

It is important to understand that this is not only a personal crisis. When my friend articulates here that he is not a nerd and hence Mastodon is not for him, it is not only about him. It also is about the subject position of the user being different than that of the nerd.

The Return of the Server: Infrastructure and Subjectivity

Both the user and the nerd are subject positions of technological practice. One aspect in said crisis of user subjectivity is what I call “the return of the server.” Even if scale is an important aspect for user experience, the difference between Twitter and Mastodon is not only one of numerical scale in terms of user count, but first and foremost one of organization on an infrastructural level. Twitter operates as a centralized platform; it is a unified service accessed through an app, and its data and processes are located in the cloud. Mastodon, however, runs on a decentral network of federated1 servers connected by a shared protocol.

Of course, technically speaking big technologies and the cloud also operate on servers. Servers are still the main nodes in the infrastructure of the Internet: it is on servers that data is stored and where user requests are processed. But on big tech platforms, servers have been abstracted away in order to make technical systems scalable (Monroe). Servers have disappeared from the view of users due to this recent additional step in the chain of abstractions on which digital infrastructure is built. And with it, a contextual and materialist understanding of digital infrastructure disappeared as well. Specific machines, local contexts, and a diversity of practices turned into immaterial services and apps. Servers have been replaced with the cloud, a metaphor suggesting quite the opposite of the massive, energy-hungry data centers powering large scale digital infrastructure. Thus, in the age of cloud computing, we simply cannot know the number of servers Twitter is running on.

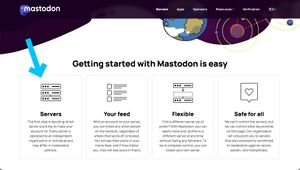

Fig. 2: Screenshot of the sign-up page on https://joinmastodon.org (08.06.2023)

The return of the server happens very prominently at the first step of the signup process for Mastodon. Here, Mastodon asks users to pick a server and hence a specific context to join. In order to answer this, users need to identify themselves in ways that are different than on big technology platforms. When signing up to a commercial platform, users are asked to identify themselves as a classical autonomous (self-contained) liberal individual. In contrast, the sign-up process for Mastodon asks users to choose a server, which means identifying themselves in relation to a community first.

In the 1960s, Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser explained that the social and political order of the world are continuously updated in individuals by means of a process he called “interpellation.” In his view, the subject does not exist independently of its surroundings, but is created and sustained (hailed) through calls of institutions (Althusser et al.), and in the context of this text: infrastructures. It is through their infrastructural organization that Twitter and Mastodon interpellate their users, and, as we have seen, this interpellation brings forward different imaginations of what a user is. This means that subjectivity is never only personal, or interior, but that the personal, the psychological, and the individual are deeply linked to the world and its social, economic, political, and cultural formations. My friend’s interpretation of the sign-up process for Mastodon as nerdy points to an understanding of servers being outside of the domain of users and—as technological artifacts—belonging to the nerd. But it also points to something deeper: as the sign-up process of Twitter indicates, contemporary user subjectivity is closely aligned with liberal subjectivity. This autonomous, calculating and self-regulating subject is a subject position in itself, serving as a background of user subjectivity. Hence, the process of infrastructural interpellation is not a deterministic process, but operates in relation to other callings, self-understandings, and already established subject positions. Infrastructural interpellation can be confirming existing normative subject positions, but as we have seen with Mastodon, it can also result in tensions. These tensions articulate not only a problem, but also a space for difference. Thus, interpellation through technology is a performative process that consists of numerous performative gestures that maintain identity, but also bear the possibilities of difference (Butler). This means that subjectivity is a place of being affected by the world, but also a place where change can happen.

Being a User between Individual and Community

As I have discussed, the request to choose a community at the beginning of an identification process creates tension between the conventions of the liberal subject (where communities always come after the subject) and the specific affordances of federation as infrastructural organization, which centers the communities around servers.

This tension sparked a long debate in the Mastodon community about the difficulties newcomers experience with the sign-up process. At this point, a list of servers to join was provided on https://joinmastodon.org (the privileged information site for joining Mastodon). But due to the quick expansion of the Mastodon network, the list quickly grew into a cluttered, overwhelming list of servers that no one was able to seriously consider for orientation.

In order to make it easier for people willing to join, the first move was to solve the problem by meeting the expectations of users (and with copying it the conventions of corporate platforms), and giving up the list in favor of promoting only one server: mastodon.social. Mastodon.social is one of the biggest instances (servers) operated by Mastodon GmbH,2 a nonprofit organization run by Eugene Rochko that is registered in Berlin (Eugene Rochko is the developer of Mastodon, but not the owner3).

This earned sweeping critique from the community, which highlighted the dangers of centralization for the whole ecosystem and insisted on the nature of federation being exactly about community-centered infrastructure. Eventually, this was resolved by again putting up an overview of servers, but this time with the ability to filter it by regions and topics, language, and other types of differences. This solution is a strategy to remain loyal to federation- and community-based infrastructures by making the wealth of communities legible in order to facilitate choice.

Fig. 3: Screenshot of the server list on https://joinmastodon.org/servers (08.06.2023)

Fig. 4: Screenshot of the sign-up process start on the official Mastodon app (31.05.2023)

On the official mobile app (named Mastodon and also maintained by Mastodon GmbH), however, new users are still presented with mastodon.social as the default server. In order to choose another server, users are taken to the list on https://join.mastodon.org, which is a website outside the app. Thus, joining servers other than mastodon.social is discouraged by a complicated process that is difficult for newcomers to navigate. This difference in sign-up procedures on the web and in the app mirrors the tension of how users are conceptualized through technology: as a member of a community around federated servers versus a self-contained liberal individual of a service.

To conclude this analysis: Mastodon suggests a different user subject position than corporate big technology platforms: one oriented towards a community, and not an atomic, isolated self-contained individual. This interpellation comes from the technical principle of the federation of independent servers. The difference in interpellation leads to tensions both on the part of users as a crisis in subjectivity, as well as on the part of the platform handling its onboarding process. But while opening the user subject position towards communality, Mastodon still upholds the difference between users and those involved with providing the infrastructure: the administrators, the programmers, and the moderators. Thus, the user subject position offered by Mastodon is still a consumer, clearly separate from that of the producer and the provider of the service, as with big tech platforms.4